Lymphedema

JAMES LAREDO and BYUNG BOONG LEE

Presentation

A 56-year-old man with a history of recurrent lower extremity cellulitis is referred by his primary medical doctor for chronic bilateral lower extremity swelling. He reports a 5-year history of progressive swelling of his lower extremities involving his feet, toes, ankles, and calves. He notes hardening of the skin of his legs below the knees and development of wartlike lesions. He was initially treated with compression stockings, but has been noncompliant over the past 5 years. He denied any history of deep vein thrombosis or history of varicose veins. There was no family history of leg swelling.

Differential Diagnosis

Leg edema is a common condition that is seen by all practicing clinicians. The differential diagnosis of lower extremity edema is extensive and includes systemic causes such as congestive heart failure, renal insufficiency, hepatic insufficiency, hypoalbuminemia, medications, and local causes such as deep vein thrombosis, venous insufficiency, lymphedema, lipedema, and cellulitis.

Workup

On physical examination, the patient is an obese man with normal arterial pulses in both lower extremities. There is no groin adenopathy. He has nonpitting edema of the bilateral lower extremities below the knees, with warty projections, lichenification, cobble stoning of the skin, and a malodorous fungal infection. There was no ulceration or drainage. Both feet had the presence of the Stemmer sign (inability to pinch a fold of skin at the base of the second toe) and puffiness of the forefoot (buffalo hump) (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1 Bilateral lower extremity lymphedema in a 56-year-old man before and after complex decongestive therapy. A: Before treatment. Note the significant limb swelling and chronic skin changes (lichenification, warty projections, and cobblestone appearance) associated with lymphedema. B: After treatment. Note the significant improvement in limb swelling and chronic skin changes.

Venous duplex exam of the bilateral lower extremities was negative for deep vein thrombosis and venous insufficiency. Based on the presentation and past history of recurrent bilateral lower extremity cellulitis, a diagnosis of secondary lymphedema is made.

To confirm the diagnosis, bilateral lower extremity lymphoscintigraphy was performed.

Lymphoscintigraphy

Subcutaneous injection of radiolabeled sulfur colloid is administered in the first and second web space of the toes of both feet, followed by radionuclide scanning.

Delayed isotope egress from the injection site, with decreased uptake and dermal back flow, was seen consistent with lymphedema.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Secondary lymphedema: Stage III

The patient was treated with a combination of compression wrapping, manual lymphatic drainage (MLD), and pneumatic compression therapy. Meticulous skin care including topical antifungal cream and skin moisturizers and skin cleansers was also part of his treatment regimen. Because of his history of recurrent lower extremity cellulitis, the patient was started on prophylactic antibiotic treatment with daily oral penicillin.

Lymphedema

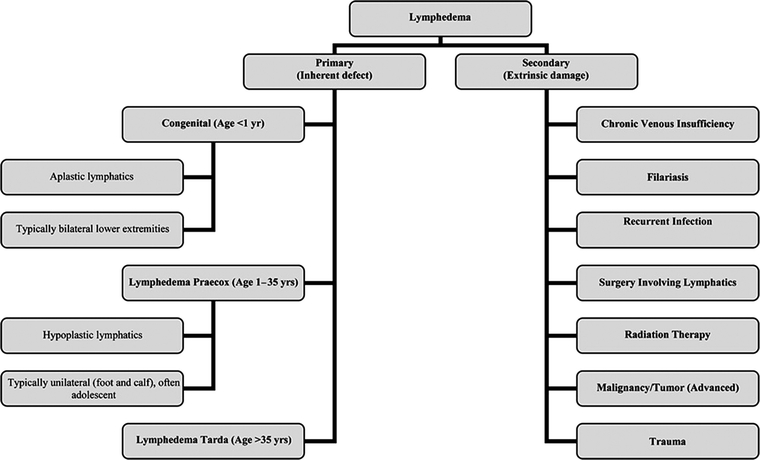

Lymphedema is characterized by a progressive and usually painless swelling of tissues, most commonly involving the lower extremities in 80% of cases. It can also occur in the arms, face, trunk, and external genitalia. Lymphedema is the result of decreased transport capacity of the lymphatic system. Lymphedema can be primary or secondary (Fig. 2). Primary lymphedema is due to a defect in the lymph-conducting pathways. Secondary lymphedema is due to an acquired cause that results in injury and impairment of the lymphatic system.

FIGURE 2 Primary and secondary lymphedema. Lymphedema is the result of decreased transport capacity of the lymphatic system. Lymphedema can be primary or secondary. Primary lymphedema is due to a defect in the lymph conducting pathways. Secondary lymphedema is due to an acquired cause. (From Kerchner K, Fleischer A, Yosipovitch G. Lower extremity lymphedema update: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(2):324–331.)

Primary lymphedemas have been classified into three groups depending on the age of onset: congenital (before age 2), praecox (onset between age 2 and 25), and tarda (after age 35). Lymphedema praecox is the most common form of primary lymphedema with a female-to-male ratio of 10:1. It is usually unilateral and often limited to the foot and calf in most patients.

Secondary lymphedema is far more common than primary lymphedema and represents 90% of cases of lymphedema. The most common causes of lower extremity lymphedema are tumor (e.g., lymphoma, prostate cancer, ovarian cancer), surgery involving the lymphatics, radiation therapy, trauma, and infection.

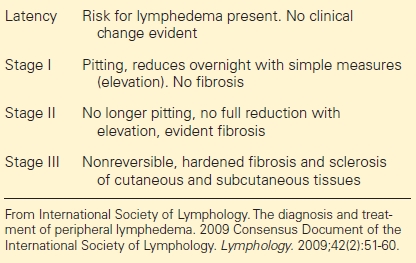

Stages of Lymphedema

Treatment of Lymphedema

General Considerations

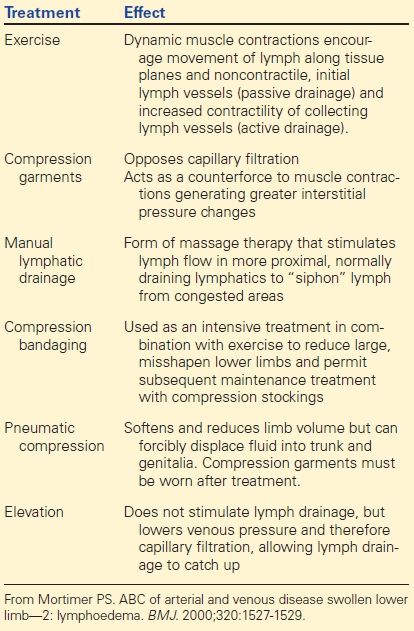

The importance of patient education and compliance cannot be overemphasized when treating patients with lymphedema. The patient must first understand that lymphedema is a chronic condition and will never be completely cured. In addition, they must also understand that there is no “quick fix” operation, medication, or therapy that will completely reverse the clinical condition. Treatment of lymphedema is essentially management of the medical condition and prevention of progression of the disease process. Lymphedema can be successfully managed (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Stages of Lymphedema

The goals of lymphedema therapy are to arrest progression, reduce swelling, maintain that reduction, prevent infection, restore mobility and range of motion, and train patients for self-management.

Physical Treatments

Physical treatment to reduce swelling is aimed at controlling lymph formation and improving lymph drainage through existing lymphatic vessels and collateral routes by applying normal physical processes that stimulate lymph flow (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Physical Treatments for Lymphedema