Chapter 53 Lymphedema

Lymphedema is an important topic for vascular surgeons for three reasons. First, it is highly common. Estimates vary, but hundreds of thousands of patients in the United States have lymphedema,1 and hundreds of millions are affected worldwide according to the World Health Organization.2 Second, even the best surgeons may have patients who develop lymphedema after operations involving the limbs or trunk. Third, lymphedema may be confused with venous disease or other vascular anomalies that are typically referred to vascular surgeons. For these reasons, vascular surgeons are likely to encounter patients with lymphedema.

Pathogenesis

Fluid, proteins, and various soluble substances extravasate from the capillaries into the interstitial space.3 This fluid is removed through venous capillaries and lymphatic vessels, which provide equilibrium between the amount of fluid released into the interstitium and that removed from it. Fluid transported by the lymphatic vessels carries macromolecules and is rich in protein, increased concentrations of which raise osmotic pressure of the tissues by binding fluid in the interstitium.4 Interstitial fluid is called lymph fluid once it enters the lymphatic vessel. If the flow of lymphatic fluid through the lymphatic vessels is hindered, it accumulates in the tissues producing edema.

Normal lymphatic vessels exhibit spontaneous regular rhythmic contractions that pump fluid centripetally. This process is independent of hydrostatic pressure, muscle contractions, or external pressure in healthy individuals. These mechanisms become important for maintaining fluid flow when lymphatic vessels are damaged. Various insults may produce a range of lymphatic vessel abnormalities, such as total obstruction of lymphatic trunks in erysipelas, vessel wall changes in staphylococcal dermatitis or after trauma. Progressive stages of lymphedema are marked by increasing abnormalities of the lymphatic vessel contractions leading to stasis and increased tissue pressure.5

Lymphedema occurs when interstitial fluid accumulates because of lymphatic obstruction or reflux (or rarely from extreme overproduction of lymph fluid). Over time, inflammatory alterations in connective tissues marked by altered cytokine production, accumulation of plasma proteins, and fibrous proliferation with deposition of collagen lead to dermal fibrosis. The brawny or woody texture of lymphedema (Figure 53-1) is thought to be caused by chronic inflammation associated with the excessive interstitial protein trapping that overwhelms intrinsic neutrophil and macrophage proteases.6 Paradoxically, the protein concentration of the interstitial fluid in the swollen arm of patients with breast cancer-related lymphedema is lower than that in the contralateral arm, and correlates negatively with the degree of swelling. In addition to mechanical obstruction and inflammation, other factors, including impaired capacity for lymphangiogenesis causing a reduced number of collaterals and lymphovenous communications, may contribute to lymphedema formation.7

Causes

Lymphedema may be either primary or secondary, resulting from either the failure of lymphatics to develop normally or from the degeneration and loss of lymphatics over time. Primary lymphedema may occur shortly after birth (heritable forms include Milroy disease),8,9 around the time of puberty (lymphedema praecox),9 or rarely during adulthood (lymphedema tarda).10 Phenotypic characterization of the genetic defects has been possible for some forms of primary lymphedema.11 More than 30 mutations in vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 (VEGFR3 or FLT4) have been identified for Milroy disease. Because of incomplete penetrance, presence of these mutations results in lymphedema in 64% to 90% of all patients. In this condition, skin lymphatics are abundant but are nonfunctional.11 In lymphedema-distichiasis, the mutation is in FOXC2 with penetrance of 94% to 100%.12 The characteristic double row of eye lashes is present at birth, while lymphedema onset is delayed until puberty. Lymphedema-distichiasis may also include another disease variant known as lymphedema-ptosis syndrome.11 Hypotrichosis-lymphedema-telangiectasia syndrome is due to mutation in SOX18.13 Isolated pubertal-onset primary lymphedema (Meige disease) does not have an identified genetic defect. Many complex syndromes, such as Hennekam, Aagenaes (cholestasis-lymphedema syndrome), microcephaly-chorioretinopathy-lymphedema, Mucke, Noonan, Turner, Prader-Willi, neurofibromatosis type I (von Recklinghausen), lymphedema-hypoparathyroidism, Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber, and yellow nail syndromes, include lymphedema as a clinical feature.11,14,15

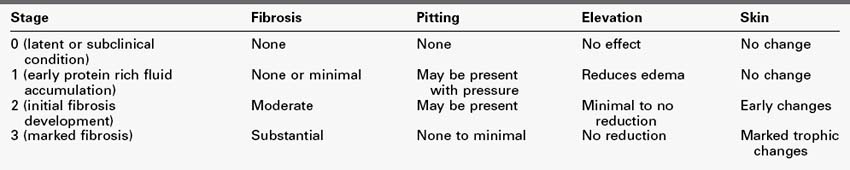

In practice, clinical grading of lymphedema (Table 53-1) is commonly used based on the physical condition of the affected tissues.16,17 Volumetric documentation and bioimpedance technologies improve diagnostic precision and may help to detect subclinical disease.18,19

Secondary lymphedema is much more common than the primary form and can result from anything that leads to the destruction of lymphatic vessels or nodes.10 In the United States and other developed countries, most cases are secondary to surgical interventions and radiation treatment, usually related to cancer.20 Incidence ranges 9% to 41% after axillary lymph node dissection, although it decreased to 4% to 10% with sentinel node biopsy.21 It remains to be seen whether new surgical approaches22,23 will become widely accepted and lead to reduction of the associated rates of lymphedema. Other common causes include trauma, surgery, radiation therapy (leads to lymphatic sclerosis), invasion of the lymphatic system by tumor, recurrent infections or lymphangitis (usually caused by streptococci or, less often, staphylococci) that obliterate the vessels, and certain parasites. Worldwide, filariasis necessitated treatment in nearly half a billion people (primarily in tropical countries) in 2009 and thus is the most common cause of lymphedema.2 The most common filariae are Wuchereria bancrofti and Brugia species.24 Although most of these are tropical organisms, some Brugia species are found in North America. Many other conditions, including autoimmune diseases, pregnancy, illegal drug injections, and factitial injuries may produce lymphedema.25–28 Risk factors for lymphedema development include weight gain or obesity, trauma, history of malignancy, family history of lymphedema, travel to the endemic geographic areas.18

Diagnosis

Lymphedema is often suspected or diagnosed on clinical grounds. Age, an appropriate history describing the circumstances leading to the onset of edema, and the presence of comorbid conditions help to discern primary and secondary lymphedema cases. In some variants of primary lymphedema, family history along with characteristic phenotypical traits may facilitate the diagnosis.11

Lymphedema is typically worse at the distal end of the extremity. However, swelling may be compartmentalized in some cases (with sparing of the most distal parts of the extremity) thus challenging the somewhat simplistic traditional “stopcock hypothesis” of impeded lymphatic flow.7 When it affects the lower limb, the feet and toes are rarely spared (Figure 53-2) unlike in lipedema, in which feet are characteristically spared.29 Indeed, chronic toe edema leads to remodeling changes that produce the “squaring” of the toes (or “boxcar toes”) classically seen in lymphedema. Stemmer sign is a classic feature of lymphedema and denotes the inability to pinch the skin on the dorsum of the second digit of the foot. Venous prominence and “ski-jump toenails” are found in Milroy disease, a form of primary lymphedema. In lymphedema-distichiasis venous varicosities, ptosis, cleft palate, congenital heart disease, spinal extradural cysts, and other abnormalities are also commonly found.11 Verrucous or papillomatous skin changes are common; these wartlike lesions can lead to unnecessary biopsies in some cases. In extreme cases, particularly those produced by tropical filariae, the limb may take on a grotesque appearance associated with massive edema, fibrosis, and verrucous changes (Figure 53-3). This appearance is commonly called elephantiasis.

It may be necessary to rule out other problems that can cause limb swelling, especially venous occlusion. This is particularly problematic when limb swelling occurs after an operation such as mastectomy or pelvic surgery (Figure 53-4), during which lymph nodes and vessels may have been damaged or removed (producing lymphedema) and veins may have been injured or thrombosed (producing venous edema). Both qualitative and quantitative assessments of lymphedema are useful.21

Duplex ultrasound scanning and venography will help to assess possible contribution of venous pathology to edema. Cross-sectional imaging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be appropriate to look for enlarged, tumor-filled lymph nodes or other lesions, such as nonmalignant masses and fluid collections, which can produce lymphatic obstruction. In addition, CT may reveal characteristic honeycomb appearances of the tissues. MRI can help to differentiate the cutaneous edema of lymphedema from other types of limb swelling, including lipedema and phlebedema.30–33 Additional methods of assessment include CT lymphography, fluorescent microlymphangiography,34 dual-emission x-ray absorptiometry, and biphotonic absorptiometry.16

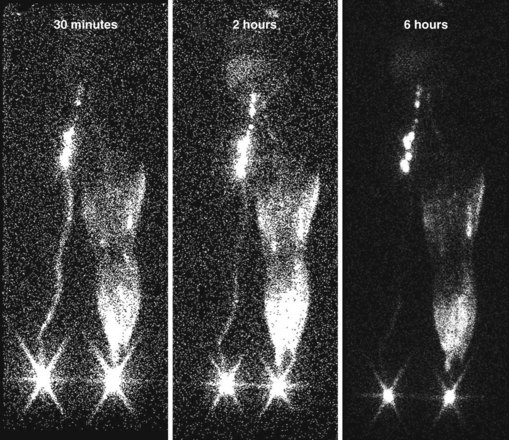

The two tests used to assess lymphatic patency are lymphangiography and lymphoscintigraphy. They provide both anatomic and functional information. Lymphangiography involves cannulation of a distal lymphatic vessel via a surgical incision.35 Contrast dye is injected into the cannulated vessel, and x-ray images are obtained. The study provides a detailed view of the lymph vessels and nodes. It is now used rarely because it is painful, technically difficult to perform, and in some cases may cause sterile lymphangitis and worsen lymphatic obstruction.36 In addition, the necessary equipment is no longer manufactured.37 Lymphoscintigraphy involves the subcutaneous injection of a radiolabeled colloid into the distal extremity.38 The colloid travels through lymphatic vessels and nodes, and its flow can be assessed using traditional nuclear imaging cameras. In normal subjects, transport to the abdominal level occurs in 1 hour or less. When lymphatic obstruction is present, the colloid never ascends the lymphatics but instead becomes trapped in the interstitial spaces of the distal limb, producing a dermal backflow pattern. Delayed transport or dermal backflow patterns identify limbs with lymphatic obstruction4,39,40 (Figure 53-5).

Many scales exist and precision of lymphedema grading depends on the purposes (clinical vs. research) and varies in terms of time and cost.41 Quantification of lymphedema is clinically meaningful and is commonly performed by simple circumferential measurements at 4-cm intervals using a measuring tape. The more sophisticated methods include volumetry, optoelectronic volumetry (perometry),42 quantitative lymphoscintigraphy,43 and bioimpedance spectroscopy.19 Tonometry measures resistance of tissues to compression.44 No single standard of lymphedema severity assessment exists, and the choice of specific methods varies among institutions.

Several immunohistochemical markers can aid the examination of the lymphatic system.45,46 However, there is a scarcity of basic research of the lymphatic system, at least partially owing to the lack of animal models.47–49

In addition to venous disease, there are other conditions that can mimic the clinical appearance of lymphedema. Myxedema associated with thyroid dysfunction, cardiac or renal failure, hypoproteinemia, and chronic dependency can resemble lymphedema or aggravate otherwise mild cases of lymphedema.50 Obesity (including morbid obesity and lipedema) is frequently seen in conjunction with lymphedema or is mistaken for it.

Rationale for Treatment

Lymphedema is almost never life-threatening; the goals of treatment are to improve limb function, reduce pain, improve cosmesis, and prevent long-term complications. Lymphedema is generally an incurable, chronic disease that often requires life-long care.16 Natural history of the disease is characterized by progression both in terms of the amount of lymphedema and its grades. This progression is slower for primary cases compared to secondary ones, and slower for arms than for legs. In general, secondary lymphedema cases are marked by accelerated fibrosis.17 Adverse psychological effects of lymphedema can be significant.

The rationale for therapy directed at pain relief, functional improvement, or appearance seems obvious. Therapy intended to prevent future complications is less intuitive but often is of greater importance. Limbs with lymphedema are at risk for numerous problems, including increased susceptibility to injury, infections such as cellulitis or lymphangitis (Figure 53-6; both of which lead to progressive destruction of lymphatics and increasing edema), and tumor formation (particularly angiosarcoma or Stewart-Treves syndrome).51 It may be difficult to appreciate the importance of lymphedema treatment for the prevention of complications in patients with no limb pain, no functional impairment, and no cosmetic concerns. However, the ensuing complications can be devastating when patients develop cellulitis or lymphangitis that ravages the remaining lymphatics and leaves the limb dysfunctional with severe lymphedema. Even more devastated are the patients who develop angiosarcoma, a condition that usually leads to rapid loss of the limb and life (5-year survival time, 10% to 16%; mean survival, 19 to 31 months).52–55