Lung Cancer: Epidemiology and Carcinogenesis

Charles S. Dela Cruz

Lynn T. Tanoue

Richard A. Matthay

Carcinoma of the lung is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States and around the world. The sheer magnitude of the lung cancer epidemic is staggering. Jemal and colleagues67 projected that 215,020 new cases of lung cancer would be diagnosed in the United States in 2008. At present, more people in this country succumb annually to lung cancer than die from cancers of the colon, breast, and prostate combined. Pisani99 and Parkin93 and their colleagues have reviewed the most recent available global cancer estimates for the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Because these statistics reflect

data from 2002, they likely underestimate the current global lung cancer threat. Lung cancer has been the most common cancer in the world since 1985. In 2002, lung cancer continues to be the most common cancer worldwide in terms of both incidence and mortality. Lung cancer was the largest single contributor to new cases of cancer diagnosed (1,350,000 new cases, equaling 12.4% of total new cancer cases) as well as to mortality from cancer (1,180,000 deaths, equaling 17.6% of total cancer deaths). Almost half (49.9%) of the cases occur in the developing countries, a significant change since 1980, when 69% of the cases were in developed countries. The estimated numbers of lung cancer cases worldwide has increased by 51% since 1985 (+44% in men and +76% in women).99

data from 2002, they likely underestimate the current global lung cancer threat. Lung cancer has been the most common cancer in the world since 1985. In 2002, lung cancer continues to be the most common cancer worldwide in terms of both incidence and mortality. Lung cancer was the largest single contributor to new cases of cancer diagnosed (1,350,000 new cases, equaling 12.4% of total new cancer cases) as well as to mortality from cancer (1,180,000 deaths, equaling 17.6% of total cancer deaths). Almost half (49.9%) of the cases occur in the developing countries, a significant change since 1980, when 69% of the cases were in developed countries. The estimated numbers of lung cancer cases worldwide has increased by 51% since 1985 (+44% in men and +76% in women).99

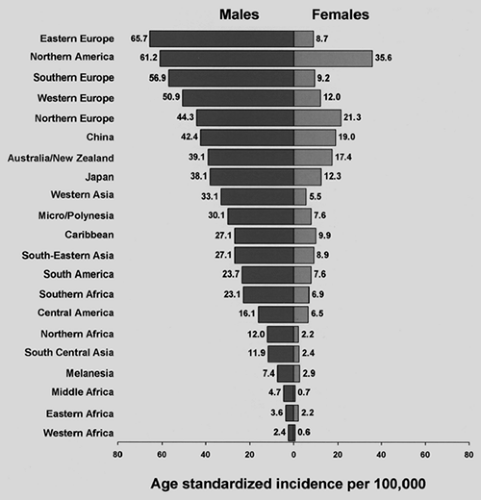

Figure 101-1. Annual age-adjusted cancer death rates for males by site, United States, 1930–2004. (From Jemal A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin 2008;53:5, 2008. With permission.) |

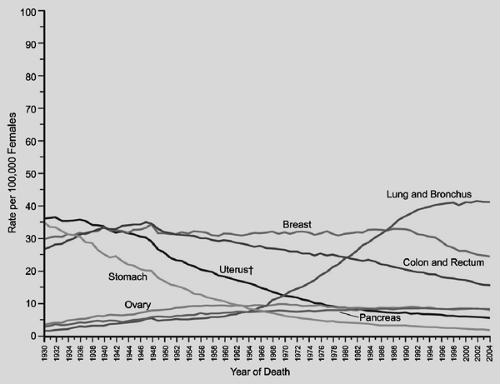

In the United States, lung cancer incidence in males has been decreasing since the early 1980s. Incidence and mortality rates for lung cancer tend to mirror one another, because most persons who are diagnosed with lung cancer eventually succumb to it. Jemal and colleagues67 in their review of cancer statistics for 2008 noted decreases in death rates from lung cancer in men by 2.0% per year from 1994 to 2004 (Fig. 101-1). In women, however, lung cancer incidence rates continue to increase by 0.2% per year from 1995 to 2004. On an optimistic note, incidence rates among women <65 years of age declined from 28.3% per 100,000 women in 1991 to 22.7% per 100,000 women in 1998. Unfortunately lung cancer death rates among women have not decreased, but appear to be reaching a plateau, which represents an encouraging change from the steep rise witnessed in the 1970s to 1980s (Fig. 101-2). Cancer of the lung and bronchus still accounts for 31% of cancer deaths in men and 26% of cancer deaths in women in the United States.

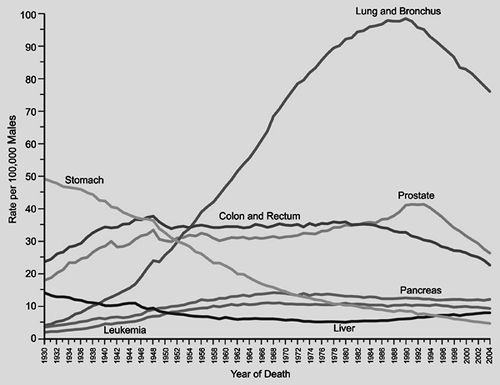

The lung cancer situation in the United States is a harbinger for the situation globally. Lung cancer incidence and mortality are highest in the United States and the developed countries of Europe. In contrast, lung cancer rates in underdeveloped geographic areas, including Central America and most of Africa, are relatively low (Fig. 101-3). However, the World Health Organization135 estimates that lung cancer deaths worldwide will continue to rise, largely due to increasing global tobacco use, especially in China and India. The enormity of the lung cancer problem mandates examination of the epidemiology of the disease. Currently, despite the availability of new diagnostic technologies, advancements in surgical techniques, and the development of nonsurgical treatment modalities, the overall 5-year survival rate for lung cancer in the United States remains a dismal 15%. The situation globally is even worse, with 5-year survival in Europe, China, and developing countries estimated at 8.9%. Given this, prevention should be a major focus of the efforts currently being made in this field. Understanding the epidemiology of lung cancer, including the identification of risk factors, is critically important because the modification of risks should affect the development of this disease.

Figure 101-2. Annual age-adjusted cancer deaths rates for females by site, United States, 1930–2004. (From Jemal A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin 2008;53:5, 2008. With permission.) |

This chapter focuses primarily on a discussion of modifiable risk factors, including tobacco smoking, exposure to occupational carcinogens and ionizing radiation, and diet. The genetic aspects of carcinogenesis will be discussed.

Tobacco Smoking

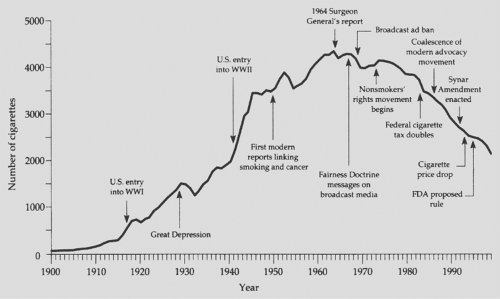

Tobacco has been a part of the cultural and economic structure of this country since the time of Columbus. It was originally chewed or smoked in pipes, and cigarettes became widely available after the development of cigarette wrapping machinery in the mid-1800s. Prior to World War I, cigarette use in the United States was modest. Wynder and Graham139 estimate that in 1900, the average annual adult consumption of cigarettes was <100 per person. In 1950, this number rose to approximately 3,500 cigarettes per person per year; it reached a maximum of approximately 4,400 cigarettes per person per year in the mid 1960s.

In 1964, the U.S. Public Health Service published the Surgeon General’s landmark report on smoking and health. The principal findings of this report were as follows:

Cigarette smoking is associated with a 70% increase in the age-specific death rates of men and a lesser increase in the death rates of women.

Cigarette smoking is causally related to lung cancer in men. The magnitude of the effect of cigarette smoking far outweighed all other factors leading to lung cancer. The risk of developing lung cancer increases with duration of smoking and the number of cigarettes smoked per day. The report estimates that the average male smoker has an approximately 9- to 10-fold risk of developing lung cancer, whereas heavy smokers have at least a 20-fold risk.

Cigarette smoking is believed to be much more important than occupational exposures in the causation of lung cancer in the general population.

Cigarette smoking is the most important cause of chronic bronchitis in the United States.

Male cigarette smokers have a higher death rate from coronary artery disease than nonsmoking men.

At the conclusion of the report, the following statement was made: “Cigarette smoking is a health hazard of sufficient importance in the United States to warrant appropriate remedial action.” Since the submission of this report, yearly per capita consumption of cigarettes has declined in the United States (Fig. 101-4), although it is estimated that 20.8% of all Americans continue to smoke. On the basis of a recent report by Rock and colleagues,104 this figure has not changed significantly since about 1997. Of these smokers, 80.1%, or 36.3 million people, reported smoking every day, and 19.9% (or 9 million) smoked on some days. By sex, the prevalence of smoking was higher among men (23.9%) than among women (18.0%).

At the turn of the twentieth century, lung cancer was an uncommon disease. In 1912, Adler performed an extensive review of autopsy reports from hospitals in the United States and western European countries and found 374 cases of primary lung cancer. This represented <0.5% of all cancer cases. Adler concluded that “primary malignant neoplasms of the lung are among the rarest forms of disease.” Over the next several decades a number of authors in the United States and abroad noted an increase in the incidence of carcinoma of the lung. In a series of 185,434 autopsy cases collected between 1897 and 1930, Hruby and Sweany62 noted that the incidence of lung cancer had increased disproportionately to the incidence of cancer in general.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, it was postulated that the observed increase in lung cancer might be due to a variety of etiologies, including influenza, tuberculosis, irritating gases, atmospheric pollution from industrial plants and coal fires, and chronic bronchitis. The appreciation that tar could produce lung carcinoma when applied experimentally to the skin of animals raised preliminary concern that inhalation of tar products originating from automobile exhaust or the surface dust of tarred roads could be important factors in the observed rise in lung cancer incidence. As early as 1930, Roffo106 concluded, from observations made in patients and experimental studies in animals, that tobacco tar liberated from the burning of tobacco was a carcinogenic agent. By the 1920s and 1930s, a number of uncontrolled series called attention to the potential role of cigarette smoking in the observed increase in lung cancer incidence. Fahr,46 Lickint,72 McNally,80 Roffo,106 Ochsner and DeBakey,89 Tylecote,126 and Levin and colleagues,71 among others, voiced a growing concern that the increase in lung cancer was due to the growing use of cigarettes. In 1941, Ochsner and DeBakey90 stated, in a review of carcinoma of the lung, “It is our definite conviction that the increase in the incidence of pulmonary carcinoma is due largely to the increase in smoking.”

In 1950, two landmark epidemiologic studies evaluating the role of tobacco smoking as an etiologic factor in bronchogenic carcinoma were published. Wynder and Graham139 in the United States reported a case control study examining 605 cases of lung cancer in men compared with a general male hospital population without cancer. The most striking finding was that 96.5% of lung cancers were found in men who were moderate to heavy smokers for many years, compared with the general population, which had a smoking rate of 73.7%. Several important conclusions were drawn in this study: (a) excessive and prolonged use of tobacco was an important factor in the induction of lung cancer, (b) the occurrence of lung cancer in a nonsmoker was a rare phenomenon, and (c) a lag period of 10 years or more between smoking cessation and the clinical onset of carcinoma could be observed. This report was closely followed by a similar case control study done in the United

Kingdom by Doll and Hill.41 They interviewed 649 male and 60 female lung cancer subjects at 20 London hospitals and compared them with 1,029 subjects who had cancer in organs other than the lung and 743 general medical and surgical patients matched for age and sex. In this study, 0.3% of men and 31.7% of women with lung cancer were nonsmokers, compared with 4.2% of men and 53.3% of women without cancer. Like Wynder and Graham, these authors concluded that an association between carcinoma of the lung and cigarette smoking did indeed exist and that the effect on the development of lung cancer varied with the amount of cigarette use.

Kingdom by Doll and Hill.41 They interviewed 649 male and 60 female lung cancer subjects at 20 London hospitals and compared them with 1,029 subjects who had cancer in organs other than the lung and 743 general medical and surgical patients matched for age and sex. In this study, 0.3% of men and 31.7% of women with lung cancer were nonsmokers, compared with 4.2% of men and 53.3% of women without cancer. Like Wynder and Graham, these authors concluded that an association between carcinoma of the lung and cigarette smoking did indeed exist and that the effect on the development of lung cancer varied with the amount of cigarette use.

Cigarette smoke is a complex aerosol composed of both gaseous and particulate compounds. It is broken down into mainstream smoke and sidestream smoke components. Mainstream smoke is produced by inhalation of air through the cigarette and is the primary source of smoke exposure for the smoker. Sidestream smoke is produced from smoldering of the cigarette between puffs and is the major source of environmental tobacco smoke. The primary determinant of tobacco addiction is nicotine. Tar is defined as the total particulate matter of cigarette smoke after nicotine and water have been removed. Tar exposure appears to be the major link to lung cancer risk. The Federal Trade Commission determines the nicotine and tar content of cigarettes by measurements made on standardized smoking machines. However, it is clear that the composition of mainstream smoke can be quite variable depending on the intensity of inhalation, which differs among individual smokers. Although filter tips decrease the amount of nicotine and tar in mainstream smoke, the effect of filter tips can also be variable, because compression of the tips by lips or fingers has been shown to affect the composition of inhaled smoke.

More than 4,000 individual constituents of cigarette smoke have been identified. Hoffmann and Hoffmann58 and Burns,22 in extensive reviews of cigarettes and smoke composition, note that 95% of the weight of mainstream smoke comes from 400 to 500 individual gaseous compounds. The remainder of the weight is made up of >3,500 particulate components. This does not include additives such as flavorings, which are considered trade secrets and are often unknown.

It is clear that mainstream smoke contains a large number of potential carcinogens, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, aromatic amines, N-nitrosamines, and miscellaneous organic and inorganic compounds such as benzene, vinyl chloride, arsenic, and chromium (Table 101-1). Compounds such as the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and N-nitrosamines require metabolic activation to reach carcinogenic potential. Detoxification pathways also exist, and the balance between activation and detoxification likely affects individual cancer risk. Radioactive materials such as radon and its decay products, bismuth and polonium, are also present in tobacco smoke.

The agents that appear to be of particular concern in the etiology of carcinoma of the lung are the tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines (TSNAs) formed by nitrosation of nicotine during both tobacco processing and smoking. Eight TSNAs have been described, including 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK), which is known to induce adenocarcinoma of the lung in experimental animal models. Other TSNAs have been linked to cancers of the esophagus, bladder, pancreas, oral cavity, and larynx. Of the TSNAs, NNK appears to be the most important inducer of lung cancer. It has carcinogenic effects with both topical and systemic administration. Inhalation of tobacco smoke containing TSNAs results in direct delivery of carcinogens to the lungs. Because these compounds are also absorbed systemically, hematogenous delivery to lung via the pulmonary circulation occurs as well.

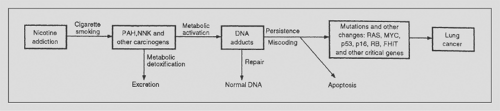

Tobacco carcinogens such as NNK can bind to DNA, creating DNA adducts. Repair processes may remove these DNA adducts and restore normal DNA, or cells with damaged DNA may undergo apoptosis. However, failure of the normal DNA repair mechanisms to remove DNA adducts may lead to permanent mutations. As outlined in a schema by Hecht,53 mutations in critical oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes may contribute to the development of lung cancer (Fig. 101-5).

The IARC has identified at least 50 carcinogens in tobacco smoke. It is important to note that the dosage of smoke constituents to the smoker can be highly variable, depending not just on the cigarette itself but also on the pattern of smoking. Specifically, the duration and intensity of inhalation, the presence and competence of a filter, and the duration of cooling of the smoke prior to inhalation can all change the composition of smoke. Over the last several decades, the nicotine and tar content of cigarettes has been lowered. However, the primary factor determining intensity of use of cigarettes is the smoker’s nicotine dependence. Thus, although cigarettes now contain less nicotine and tar than previously, smokers tend to smoke more intensively in order to satisfy their nicotine need, with higher puffs per minute and deeper inhalations. In such situations the measurements of tar and nicotine content made by smoking machines may significantly underestimate individual exposure.

Wynder and Hoffmann140 proposed an intriguing hypothesis as to how low-yield filtered cigarettes might be a contributing factor to the observed increase of adenocarcinoma versus squamous cell carcinoma of the lung over the last several decades. As stated previously, the nicotine-addicted smoker will smoke low-yield cigarettes far more intensively than older nonfiltered higher-yield cigarettes. With deeper inhalation, higher-order bronchi, as opposed to the major bronchi alone, in the peripheral lung will be exposed to carcinogen-containing smoke. These peripheral bronchi lack protective epithelium and are being exposed to carcinogens, including TSNAs linked to the induction of adenocarcinoma. Data from several laboratories, including those of Hoffmann,59 Belinsky,16 and Ronai107 and their colleagues, have documented that NNK is associated with DNA mutations resulting in the activation of K-ras oncogenes. Rodenhuis and Slebos105 reported that K-ras oncogene activation has been identified in 24% of human lung adenocarcinomas. Of note, Westra and colleagues133 have reported that K-ras mutations are present in adenocarcinoma of the lung found in ex-smokers, suggesting that such mutations do not revert with the cessation of tobacco smoking. This may in part explain the persistent elevation in lung cancer risk in ex-smokers even years after discontinuing cigarette use.

There is no doubt that tobacco smoking is the most important modifiable risk factor for lung cancer. Pisani and colleagues100 estimated that 20% of all cancer deaths worldwide could be prevented by the elimination of tobacco smoking. It is clear that individual susceptibility is also a factor in carcinogenesis. Although over 80% of lung cancers occur in persons with tobacco exposure, <20% of smokers will ever develop lung cancer. The variability seen in susceptibility must presumably

be influenced by other environmental factors or by genetic predisposition.

be influenced by other environmental factors or by genetic predisposition.

Table 101-1 Tumorigenic Agents in Tobacco and Tobacco Smoke: Evidence for IARC Evaluation of Carcinogenicity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Genetic Factors

A lung cancer risk prediction analysis was recently developed by Spitz and coworkers118 that incorporated multiple variables such as smoking history, environmental tobacco smoke, occupational exposures to dusts and to asbestos, and family history of cancer. These investigators showed the influence of positive family history of cancer to the risk of lung cancer in never smokers, former smokers, and current smokers (Table 101-2). Cassidy and colleagues28 highlighted the significant increased risk of lung cancer specifically for individuals with a family history of early-onset lung cancer (i.e., those <60 years of age) (Table 101-3). Over the last 20 years, there has been an explosion in molecular biology and genetics that allowed for the completion of the Human Genome project in 2003. Schwartz and colleagues112 recently reviewed the molecular epidemiology of lung cancer, focusing on a number of host susceptibility genetic markers to lung carcinogens. The susceptibility genetic factors included high-penetrance, low-frequency genes and low-penetrance, high-frequency genes, as well as acquired epigenetic polymorphisms. Work by Takemiya122 and Yamanaka141 and their coworkers showed the association of lung cancer with rare Mendelian cancer syndromes such as Bloom’s and Werner’s syndromes, respectively. Studies on familial aggregation have lent support to the idea that there is a hereditary component to the risk of lung cancers. These familial association approaches have been used to discover high-penetrance, low-frequency genes. A recent meta-analysis involving 32 studies showed a twofold increased risk of lung cancer in individuals with a positive family history of lung cancer. This increased risk associated with family history was still present amongst nonsmokers, as shown by Matakidou and colleagues.78 Bailey-Wilson and colleagues,12 using family linkage approaches, reported the first association of familial lung cancer to the region on chromosome 6q23-25 (146cM-164cM). The addition of smoking history to the effect of this inheritance was associated with a threefold increased risk in lung cancer. The search for the responsible lung cancer genes is being actively pursued.

There have also been numerous studies on candidate susceptibility genes that are of low penetrance and high frequency. The

approach has been to target genes known to be involved in the absorption, metabolism, and accumulation of tobacco or other carcinogens in lung tissue, with the hypothesis that these genes will affect cancer susceptibility. For example, genetic polymorphisms encoding enzymes involved in the activation and conjugation of tobacco smoke compounds such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), nitrosamines, and aromatic amines have been widely studied. The metabolism of these compounds occurs through either phase I enzymes (oxidation, reduction, and hydrolysis) or phase II (conjugation) enzymes. Some of the frequently studied enzymes in this system include CYP1A1, the glutathione S-transferases (GSTs), microsomal epoxide hydrolase 1 (mEH/EPHX1), myeloperoxidase (MPO), and NAD(P)H quinine oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1). Data on polymorphisms in CYP1A1 and their association with lung cancer risk have been conflicting. A meta-analysis involving 16 studies by Le Marchand and colleagues69 demonstrated no significant risk associated with the CYP1A1 Ile462Val allele; however, in a pooled analysis, a significant 55% increased risk in whites was observed, especially in women and nonsmokers for squamous cell carcinoma. Glutathione S-transferase gene products help conjugate electrophilic compounds to the antioxidant glutathione. GSTM1 in its null form occurs in 50% of the population, and studies by Benhamou and colleagues17 have shown a 17% increased risk of lung cancer in individuals who were GSTM1-null. A more recent and much larger meta-analysis, involving >53,000 case-controls, by Ye and colleagues142 showed an 18% increased risk of lung cancer among GSTMI-null individuals, but this significant association was not present when the analysis was limited to larger studies only.7 Amos and colleagues performed a genomewide association scan of tag single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in histologically confirmed non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in an effort to identify common low-penetrance alleles that influence lung cancer risk. They identified a susceptibility locus for lung cancer at chromosome 15q25.1, a region containing the nicotinic acethycholine receptor genes.

approach has been to target genes known to be involved in the absorption, metabolism, and accumulation of tobacco or other carcinogens in lung tissue, with the hypothesis that these genes will affect cancer susceptibility. For example, genetic polymorphisms encoding enzymes involved in the activation and conjugation of tobacco smoke compounds such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), nitrosamines, and aromatic amines have been widely studied. The metabolism of these compounds occurs through either phase I enzymes (oxidation, reduction, and hydrolysis) or phase II (conjugation) enzymes. Some of the frequently studied enzymes in this system include CYP1A1, the glutathione S-transferases (GSTs), microsomal epoxide hydrolase 1 (mEH/EPHX1), myeloperoxidase (MPO), and NAD(P)H quinine oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1). Data on polymorphisms in CYP1A1 and their association with lung cancer risk have been conflicting. A meta-analysis involving 16 studies by Le Marchand and colleagues69 demonstrated no significant risk associated with the CYP1A1 Ile462Val allele; however, in a pooled analysis, a significant 55% increased risk in whites was observed, especially in women and nonsmokers for squamous cell carcinoma. Glutathione S-transferase gene products help conjugate electrophilic compounds to the antioxidant glutathione. GSTM1 in its null form occurs in 50% of the population, and studies by Benhamou and colleagues17 have shown a 17% increased risk of lung cancer in individuals who were GSTM1-null. A more recent and much larger meta-analysis, involving >53,000 case-controls, by Ye and colleagues142 showed an 18% increased risk of lung cancer among GSTMI-null individuals, but this significant association was not present when the analysis was limited to larger studies only.7 Amos and colleagues performed a genomewide association scan of tag single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in histologically confirmed non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in an effort to identify common low-penetrance alleles that influence lung cancer risk. They identified a susceptibility locus for lung cancer at chromosome 15q25.1, a region containing the nicotinic acethycholine receptor genes.

Table 101-2 Multivariate Logistic Model for Lung Cancer by Smoking Status | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 101-3 Liverpool Lung Project—Multivariate Risk Model Lung Cancer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Results from the many candidate gene polymorphism studies focusing on a single polymorphism in one gene have been mixed. This has led to studies looking at gene–gene interactions, which require even larger study populations. For example, Zhou and colleagues144 (2002) studied the interaction between variants in genes coding for NAT2 (which activates arylamine cigarette smoke metabolites and deactivates aromatic amines) and mEH (which activates PAHs and deactivates various epoxides). They found significant interactions between NAT2 variants associated with certain acetylation pheynotype and mEH variants associated with certain activity level with the risk of lung cancer. For example, a twofold increased risk of lung cancer was observed in 120-pack-year smokers who had the NAT2 slow-acetylation and mEH high-activity genotype. On the other hand, in nonsmokers, a 50% decreased risk of lung cancer was observed among those with the combined NAT2 slow-acetylation and mEH high-activity genotype. Susceptibility to carcinogenic agents may also be affected by individual differences in mutagen sensitivity. Spitz and colleagues117 reviewed the phenotypic studies of DNA repair capacity and lung cancer risks. These studies are more difficult to conduct than genotyping studies.

Polymorphisms in genes involved in DNA repair enzymes active in base excision repair (XRCC1, OGG1), nucleotide excision repair (ERCC1, XPD, XPA), double-strand break repair (XRCC3), and different mismatch repair pathways have also been studied in relation to lung cancer risks. Chronic inflammation in response to repetitive tobacco exposure has been theorized to be involved in lung tumorigenesis. Genes encoding for the interleukins (IL-1, IL-6, IL-8), the cyclooxygenase enzymes (COX2) involved in inflammation, or the metalloproteases (MMP-1, -2, -3, -12) involved in repair during inflammation have been associated with lung cancer risk. A number of cell cycle–related genes have also been implicated in lung cancer susceptibility. These genes have included tumor suppressor genes p53 and p73, mouse double minute 2 (MDM2), and the apoptosis genes encoding FAS and FASL.

Wu and associates138 demonstrated that the presence of mutagen sensitivity is associated with an increased risk of lung cancer. Spitz and her group116 noted that the combined risk for lung cancer was greater in individuals with mutagen sensitivity who smoked than in individuals with either smoking or mutagen sensitivity and greater than that in nonsmokers with mutagen sensitivity alone. DNA adducts, which are pieces of DNA covalently bonded to a cancer-causing chemical such as PAH in cigarette smoke, can be measured as biomarkers to represent the degree of carcinogenesis. Several of the lung cancer susceptibility genes mentioned above have been associated with increased DNA adduct levels.

Acquired or epigenetic changes to DNA chromosome can also lead to increased lung cancer susceptibility. These events include changes such as DNA methylation, histone deacetylation and phosphorylation, all of which can affect gene expression and thus carcinogenic potential. Despite numerous genetic association studies, the specific genes responsible for the enhanced risk of lung cancer remain poorly understood. Work is under way in pooling findings to achieve greater study sample sizes in collaborative efforts such as the Genetic Susceptibility to Environmental Carcinogens (GSEC) and the International Lung Cancer Consortium.

Lung cancer susceptibility is thus determined at least in part by host genetic factors. People with genetic susceptibility might therefore be at even higher risk if they also smoked cigarettes. As technology advances, it may be possible to target subgroups identified as genetically at high risk for lung cancer for specific interventions, including intensive efforts at smoking cessation, screening, and prevention programs.

Prevention of smoking initiation would be the most logical intervention because it would prevent the sequence of events leading to cancer outlined in Figure 101-5. However, despite intensive antismoking campaigns and widespread public awareness of the risks associated with smoking, there appears to be a committed smoking cohort in this country that includes 20.8% of the population per Rock’s recent report.104 There is no question that smoking cessation can decrease the risk of lung cancer in this group. Peto and colleagues96 reported two large case-control studies from about 1950 and 1990 in the United Kingdom. In 1990, cessation of smoking had nearly halved what would have been the anticipated number of lung cancer cases. Lung cancer risk also appeared to be related to age at smoking cessation. For men who had stopped smoking at age 60, 50, 40, and 30, the cumulative risks of lung cancer by age 70 were 10%, 6%, 3%, and 2%, respectively.

Although these statistics appear to be hopeful, Jemal and colleagues,66 in an evaluation of data collected by the National Center for Health Statistics in the United States, identified a slowing in the rate of decrease of the birth-cohort trend in lung cancer mortality for whites born after 1950, which they interpreted as a reflection of the impact of increasing teenage smoking. Although there has been some debate as to whether age at initiation of smoking is an independent risk factor for lung cancer, this report would support the report of Wiencke and colleagues134 that patients in the youngest quartile of age at smoking initiation (7 to 15 years) have the highest DNA adduct levels.

Thus, while a frustratingly large percentage of persons in the United States and an increasing number of persons worldwide continue to smoke, efforts to prevent smoking initiation, particularly among children and teenagers, should be supported. Further, smoking cessation as the other method of primary prevention must be continually reinforced.

Contribution of Other Factors

Other Lung Diseases and Airway Obstructions

Several nonmalignant lung diseases have been associated with an increased risk of lung cancer. Of these, the strongest association has been shown with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Tobacco smoking is the primary cause of both lung cancer and COPD. A study by Wu and colleagues137 of women with lung cancer who had never smoked demonstrated a statistically significant association between the presence of airflow obstruction and the development of lung cancer. A number of other groups, including Cohen,31 Skillrud,115 and Tockman124 and their colleagues, have also presented evidence that airflow obstruction itself constitutes a risk for lung cancer. This conclusion is further supported by the outcomes observed by Anthonisen and associates8 in the Lung Health Study, in which a total of 5,887 male and female smokers with spirometric evidence of mild to moderate COPD were monitored over a 5-year period with or without intervention of smoking cessation or bronchodilator therapy. One of the notable findings from this study was that mortality from lung cancer exceeded that from cardiovascular disease by nearly 50%. Lung cancer was the most common cause of death, accounting for 38% of all deaths among study participants.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree