Localized Fibrous Tumors of the Pleura

Thomas W. Shields

Anjana V. Yeldandi

Localized fibrous tumors of the pleura previously have been most often classified as localized mesotheliomas of the pleura, either benign or malignant. The malignant variety also has been classified by some investigators as a fibrosarcoma. Conceptually Moran and Suster49 agree that the malignant tumor is best regarded as a fibrosarcoma of the pleura. Scharifker and Kaneko,58 among others, have suggested that the cell origin of both the benign and malignant tumors is a noncommitted mesenchymal cell present in the subserosal tissue subjacent to the mesothelial lining of the pleura and is not from the mesothelial cells of the pleura, as the earlier name implies. Despite Moran and Suster’s49 support of the term fibrosarcoma of the pleura, at present the most common term for the malignant variety is localized malignant fibrous tumor of the pleura.

The studies of Witkin and Rosai,76 England,19 el-Naggar,18 Steinetz,65 and Ordonez54 and their colleagues have supported this concept of the mesenchymal origin of both the benign and malignant localized fibrous tumors of the pleura. Additional but oblique support of this concept is the observation that a history of asbestos exposure is lacking in the patients with these tumors, although a single case reported by Metintas and colleagues43 shows an association of malignant fibrous tumor in a person exposed to tremolite asbestos. Because no immunohistochemical studies were conducted in this case, one could speculate whether it represented a localized malignant mesothelioma, which is in marked contrast to diffuse malignant mesothelioma, where asbestos exposure is recorded in more than 60% of patients.

Benign Localized Fibrous Tumors of the Pleura

Pathologic Characteristics

Gross Features

Most benign localized fibrous tumors arise from the visceral pleura on a stalk and project into the pleural space in a pedunculated manner. Sessile attachment to the pleura occurs, and inward growth into the lung parenchyma may be seen infrequently (the so-called inverted fibroma). Yousem and Flynn77 reported three intraparenchymal localized fibrous tumors, only one of which was attached to the visceral pleura. They theorized that the other two may have arisen from mesenchymal cells in the interlobular septa or even de novo in the lung tissue. Localized fibrous tumors may also occasionally develop within a fissure. The benign tumors may also arise from the mediastinal, diaphragmatic, or costal portions of the parietal pleura. Tumors in these locations, however, including those arising within a fissure or growing into the lung, often prove to be malignant. In the report of Cardillo and colleagues3 of 55 localized fibrous tumors of the pleura, 7 arose from one of these aforementioned nonvisceral pleural locations. Three of these tumors were of the malignant variety (43%), whereas only 4 of the 48 tumors arising from the visceral pleura were malignant (8%). Although many of these localized fibrous tumors arising from the parietal pleura have a broad base, it was noted by Briselli and associates2 that some of these very large tumors may have a vascular pedicle. This may be associated with increased vascularity of the lesion. Weiss and Horton72 described such a case, and to facilitate a safer resection, these investigators embolized the supplying vessel arising from the left costocervical trunk. Even with some smaller benign tumors, vascular adhesion between the tumor and the adjacent visceral or parietal pleura is not uncommon and may be troublesome at the time of operation. The benign fibrous tumors are almost always solitary and are ovoid or round. The external surface may be smooth or bosselated. According to England and associates,19 a thin, membranous capsule is present in approximately half of the cases. The size may vary greatly from a small nodule to a huge mass that may completely fill the hemithorax. Recent reports of massive (giant) localized solitary tumors of the pleura have been published by Khan and colleagues30 and Chamberlain and Taggart.4 One case of a massive tumor was noted in Cardillo and associates’ series,3 and additional case reports have been published by Weiss and Horton74 as well as by Shaker and associates.59 Regardless of the size, on cut section, the tumor is nodular and is composed of dense, whorled fibrous tissue that may, in 10% to 15% of cases, contain cyst-like structures filled with a clear viscid fluid. Calcifications may be present within the tumor.

Histologic Features

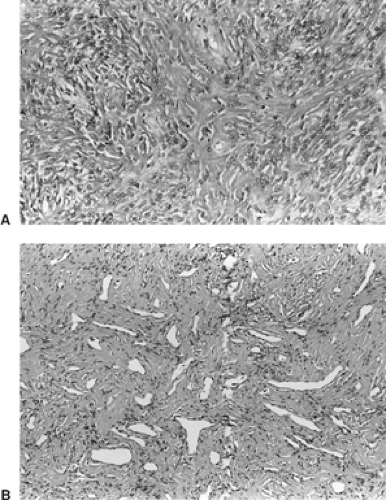

Microscopically, one or more histologic patterns may be seen. The most common pattern seen is the “patternless pattern”

described by Stout.65 Fibroblast-like cells and connective tissue are observed in varying proportions and are arranged in a disorderly or random pattern (Fig. 67-1A). The tumor cells are spindle or plump ovoid cells with round to oval nuclei and small nucleoli. Collagen and elastin bundles are readily identified. Pleomorphism and mitoses are seen infrequently. The second most common pattern is described as hemangiopericytoma-like (Fig. 67-1B) and is often combined with the patternless pattern. In this variety, closely packed tumor cells are arranged around open or collapsed, irregular branching capillaries. Other uncommon patterns, always mixed with one of the aforementioned patterns, are described as storiform, herringbone, leiomyoma-like, or neurofibroma-like. Moran and associates50 have discussed the histologic growth patterns in both the benign and the malignant solitary fibrous pleural tumors.

described by Stout.65 Fibroblast-like cells and connective tissue are observed in varying proportions and are arranged in a disorderly or random pattern (Fig. 67-1A). The tumor cells are spindle or plump ovoid cells with round to oval nuclei and small nucleoli. Collagen and elastin bundles are readily identified. Pleomorphism and mitoses are seen infrequently. The second most common pattern is described as hemangiopericytoma-like (Fig. 67-1B) and is often combined with the patternless pattern. In this variety, closely packed tumor cells are arranged around open or collapsed, irregular branching capillaries. Other uncommon patterns, always mixed with one of the aforementioned patterns, are described as storiform, herringbone, leiomyoma-like, or neurofibroma-like. Moran and associates50 have discussed the histologic growth patterns in both the benign and the malignant solitary fibrous pleural tumors.

Ultrastructural Features

Ultrastructurally, single to clusters of fusiform to round cells are found interspaced between focal or abundant collagen. The cells, according to Said and colleagues,57 most closely resemble mesenchymal cells of fibroblast type. Keating and coworkers29 noted that no basal lamina, intracellular junctions, or microvilli are seen. The observations of Briselli,2 el-Naggar,18 Steinetz,64 and Ordonez54 and their associates support the fibroblastic and myofibroblastic nature of these cells.

Immunohistologic Features

Immunohistochemically, the spindle cells that make up these tumors do not express low- or high-molecular-weight keratin reactivity, nor do they express epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, factor VIII–related antigen, neurofilament, or S-100 protein. The cells, however, have positive results with vimentin and weakly to variably positive results for muscle-specific actin. Westra73 and van de Rijn70 and their coworkers, as well as Flint and Weiss22 and Hanau and Miettinen,25 reported consistent positivity of these tumors to CD34 monoclonal antibodies. CD34 reactivity is characteristically described as present in hematopoietic stem cells, endothelium, vascular tumors, and smooth muscle tumors. Bcl-2 oncoprotein (a regulator of cell death) has been identified in both the benign and malignant spindle (fibrous) cell of these pleural tumors as well as in tumors of this cell type in other locations by Chilosi,6 Suster,67 and Hasegawa27 and their colleagues. The lack of keratin reactivity and positive CD34 antigen and bcl-2 oncoprotein differentiate these fibrous tumors of the pleura from a desmoplastic mesothelioma (Table 67-1). Li and associates34 have demonstrated the expression of basic fibroblastic growth factor in the tumor cells by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization.

Flow-Cytometric DNA and Cytogenetic Studies

El-Naggar and colleagues18 described a diploid DNA pattern in all 12 nonrecurrent benign fibrous tumors in their study. The S phase was low in all 12 as well. Miettinen and associates44 demonstrated loss or gain of chromosomes in large solitary fibrous tumors by comparative genomic hybridization, and they suggest that this might be useful in the evaluation.

Clinical Features

Benign localized fibrous tumors of the pleura occur with equal frequency in both men and women, although Milano45 reported a greater incidence in women. The tumor may occur in any age group but is more common in the fifth to eighth decades of life. More than half of the tumors are asymptomatic. Previously, Briselli and associates,2 in a review of 368 patients

with these tumors recorded in the literature, including 8 of their own cases, noted that 64% were reported to have had symptomatic lesions. However, this included many patients diagnosed late. In addition, 12% of these patients had malignant lesions. Okike53 and England19 and their colleagues have reported that chronic cough, chest pain, and dyspnea were the most common complaints (Table 67-2). Chest pain is most often manifested when the lesion arises from the parietal pleura. Pleural effusion may rarely be observed. Occasionally, in a patient with a large tumor, symptoms of bronchial compression and atelectasis may occur. A rare presentation of cardiac decompensation due to compression and displacement of the right side of the heart and inferior vena cava by a large right sided tumor of the pleura was reported by Shaker and associates.59 Okike and colleagues53 recorded the occurrence of hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy in 20% of their patients. Briselli and associates,2 in their collective review, reported an incidence of 22%. Frequently, the tumor is large (>7 cm) when this is observed. De Perrot11 and colleagues reviewed the literature and have presented clinical and histologic features with an algorithm for the management and follow-up of these patients.

with these tumors recorded in the literature, including 8 of their own cases, noted that 64% were reported to have had symptomatic lesions. However, this included many patients diagnosed late. In addition, 12% of these patients had malignant lesions. Okike53 and England19 and their colleagues have reported that chronic cough, chest pain, and dyspnea were the most common complaints (Table 67-2). Chest pain is most often manifested when the lesion arises from the parietal pleura. Pleural effusion may rarely be observed. Occasionally, in a patient with a large tumor, symptoms of bronchial compression and atelectasis may occur. A rare presentation of cardiac decompensation due to compression and displacement of the right side of the heart and inferior vena cava by a large right sided tumor of the pleura was reported by Shaker and associates.59 Okike and colleagues53 recorded the occurrence of hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy in 20% of their patients. Briselli and associates,2 in their collective review, reported an incidence of 22%. Frequently, the tumor is large (>7 cm) when this is observed. De Perrot11 and colleagues reviewed the literature and have presented clinical and histologic features with an algorithm for the management and follow-up of these patients.

Table 67-1 Differentiation of Localized Fibrous Tumor and Diffuse Mesothelioma of the Pleura: Immunoreactivity | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 67-2 Symptoms of Benign Localized Fibrous Tumors of the Pleura | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hypertrophic Pulmonary Osteoarthropathy

This symptom complex occurs in association with many intrathoracic disease processes. Clagett and colleagues7 at the Mayo Clinic reported that hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy occurred in 66% of cases of localized fibrous tumor of the pleura, although their later data, presented by Okike and associates,53 noted this association in only 20% of instances. In the latest report from this institution by Harrison-Phipps and colleagues,26 the incidence was 23% of 86 patients seen from December 1972 through December 2002. Clubbing was observed in 20% of the patients in this report. This pattern contrasts markedly with the overall 5% incidence of hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy in bronchial carcinoma. We have observed the incidence to be only 2% to 3% in this latter disease.

Osteoarthropathy describes a rheumatoid-like disease of the bones and joints. It is frequently associated with clubbing of the fingers, but it may be present without clubbing. Gynecomastia is similarly seen in association with hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy, but it also may occur as a solitary extrathoracic manifestation of an intrathoracic neoplasm.

The classic findings in hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy include stiffness of the joints, edema over the ankles and occasionally of the hands, arthralgia, and pain along the surfaces of the long bones, especially the tibia. At times, the joint and bone pain is severe.

The joint and bone involvement is usually bilateral. The distal ends of the ulna and radius are most frequently involved, and radiographic evidence of the periosteal thickening is most commonly seen here. The bones of the hands, ankles, knees, elbows, and shoulders are involved in that approximate order. Finger pressure on the anterior surface of the distal tibia often elicits pain in advance of any radiologic changes.

Clinical symptoms vary from minimally detectable stiffness of the wrists to systemic toxicity. Some of the systemic manifestations seem to be related to one or more endocrine, collagen, or immunologic mechanisms of the body that are not directly related to the osteoarthropathy. Chills and spiking temperature, markedly elevated sedimentation rate, and malaise with obvious systemic toxicity may be present.

The clinical significance of hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy is greater in its diagnostic than its therapeutic implications. Removal of the pulmonary lesion for the most part gives dramatic remission of the arthralgia and peripheral edema. In the series reported by Okike and associates,53 8 of 10 patients with localized fibrous tumors experienced complete relief of the symptom complex after operative removal of the tumor. Osseous radiographic changes regress much more slowly. Recurrence of a localized fibrous tumor is usually heralded by a return of the symptoms present with the original osteoarthropathy.

Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy may be associated with clubbing of the fingers and toes, although many investigators believe that the latter is not actually part of the syndrome. Martinez-Lavin38 and Shneerson,60 however, have suggested that the two processes are related and arise from the same underlying cause, most likely the overproduction or lack of metabolism by the lung of a growth-like hormone. Cardillo and associates3 assert that abnormal production of hyaluronic acid by the tumor cell is the cause, but no data were presented to support this statement, and there appears to be nothing in the literature concerning its role.

Clubbing

Clubbing is the enlargement of the distal phalanges, usually of both the hands and feet. There is periosteal new growth with lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration of connective tissue around the nail beds, resulting in increased fibrous tissue between the nail bed and phalanx. Van Hazel71 reported the digital arteries to be enlarged and elongated 10 to 15 times normal. Also, Cudkowicz and Armstrong9 noted the presence of arteriovenous anastomosis in the distal finger segments near the junction of the dermis and the subcutaneous tissue.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree