Previous studies have shown that smoking cessation after a cardiac event reduces the risk of subsequent mortality in patients. The aim of this study was to describe the effect of smoking cessation in terms of prolonged life-years gained. The study sample comprised 856 patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI; balloon angioplasty) during 1980 to 1985. Patients were followed up for 30 years and smoking status at 1 year could be retrieved in 806 patients. The 27 patients who died within 1 year were excluded from the analysis. The median follow-up was 19.5 years (interquartile range 6.0 to 23.0). Cumulative 30-year survival rate was 29% in the group of patients who quit smoking and 14% in persistent smokers (p = 0.005). After adjustment for baseline characteristics at the time of PCI, smoking cessation remained an independent predictor of lesser mortality (adjusted hazard ratio 0.57, 95% confidence interval 0.46 to 0.71). The estimated life expectancy was 18.5 years in those who quit smoking and 16.4 years in the persistent smokers (p <0.0001). In conclusion, in patients with coronary heart disease who underwent PCI in the late 1980s, smoking cessation resulted in at least 2.1 life-years gained.

Smoking is a well-known risk factor for the development and progression of coronary heart disease, and its relation with increased morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular causes has long been established. Previous studies have demonstrated that smoking cessation after coronary artery bypass grafting, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and myocardial infarction reduces the rate of subsequent mortality and further cardiovascular events. The aim of our study was to quantify the effect of smoking cessation in terms of prolonged life-years. We followed up the first 856 patients treated with PCI (balloon angioplasty) in the Thoraxcenter, Rotterdam during 1980 to 1985 for 30 years. Because this 30-year period almost compromises the whole further life span of these patients, the mean age at admission was 56 years, we were able to calculate the life expectancy in quitters and persistent smokers without applying major model assumptions.

Methods

The Erasmus MC, located in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, is a tertiary referral and teaching hospital in the Rotterdam region. In the 1980s, the Erasmus MC was the only hospital with PCI facilities in the Rotterdam region. Historically, the first candidates for PCI (balloon angioplasty) were those with proximal, discrete, noncalcified single-vessel obstructions in the presence of recent angina, unacceptable to the patient and uncontrolled by medical therapy. However, because of greater confidence from increased experience and technological advances, more patients with larger numbers of diseased vessels, poorer left ventricular function and more accompanying risk factors were being treated in the following years.

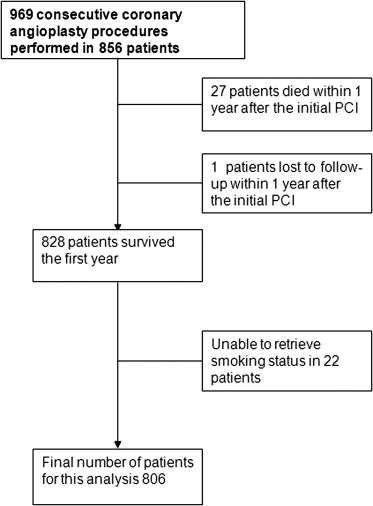

In this report, we describe the first 856 consecutive patients of 18 years of age or older who underwent PCI in the Thoraxcenter during September 1980 to December 1985 for various indications. Within 1 year after the PCI, 27 patients died and 1 patient was lost to follow-up. Among the 828 one-year survivors, smoking status could not be retrieved in 22 patients. So, our final study population consisted of 806 one-year survivors with smoking status available ( Figure 1 ).

All data on smoking status are based on self-reporting through telephonic calls and questionnaires. Patient smoking behavior was determined before the PCI procedure, and 495 patients (61%) reported to be smokers. One year after the PCI, smoking status was obtained again, and 287 patients (36%) smoked 1 year after PCI. Based on this information, patients were divided into 3 groups: nonsmokers, quitters, and persistent smokers. Patients were considered nonsmokers if they reported to never have smoked, or quitted smoking before the PCI and did not start smoking within the first year after PCI. Quitters were defined as those patients who smoked before PCI and indicated themselves as nonsmokers at 1-year follow-up. Patients were assigned to the persistent smoking category when they indicated themselves as smokers before PCI and 1 year after PCI. Two patients who started smoking within the first year after the PCI were considered as persistent smoker for this analysis.

Follow-up data for vital status were obtained from the Municipal Civil Registry in February 2011. We were able to retrieve the vital status for 838 (97.9%) of the 856 patients. Of the 18 patients whose vital status could not be retrieved, 7 patients moved abroad. For these 18 patients, we used the last known follow-up date, after which they were considered lost to follow-up. The end point of our analysis was all-cause mortality at maximum follow-up.

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD, and categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages. Student’s t tests, 1-way analysis of variance, and chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact tests) were applied, when appropriate, to evaluate differences in baseline variables among nonsmokers, quitters, and persistent smokers.

We intended to obtain complete information in all patients but failed to do so for baseline information for a small number of patients. Using missing value analysis, we evaluated the extent of missing data and searched for patterns of missing data. Missing value analysis showed that 1.6% values were missing. For the patients with ≥1 of the variables of interest missing, we decided to impute the missing values by multiple imputations.

The incidence of events over time was studied using the Kaplan-Meier method, whereas log-rank tests were applied to evaluate differences among the different groups (nonsmokers, quitters, or persistent smokers). Patients lost to follow-up were considered at risk until the date of last contact, at which point they were censored.

Subsequently, Cox proportional hazard models were used to analyze the association between smoking status and mortality during 30-year follow-up. Baseline and procedural characteristics listed in Table 1 were all considered as potential confounders. We report adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs), with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

| Characteristic | Nonsmokers, n = 309 (%) | Persistent Smokers, n = 287 (%) | Quitters, n = 210 (%) | p Value, Persistent Smokers vs Quitters | p Value, Nonsmokers vs Quitters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs), mean ± SD | 59.0 ± 8.5 | 53.8 ± 8.9 | 54.9 ± 8.9 | 0.17 | <0.001 |

| Men | 219 (71) | 251 (88) | 177 (84) | 0.31 | <0.001 |

| Indication | 0.06 | 0.041 | |||

| Stable angina pectoris | 174 (56) | 149 (52) | 100 (48) | ||

| Unstable angina pectoris | 112 (36) | 118 (41) | 81 (39) | ||

| Acute myocardial infarction | 23 (7.4) | 20 (7) | 28 (13) | ||

| Hypercholesterolemia | 87 (29) | 83 (29) | 57 (27) | 0.66 | 0.78 |

| Hypertension | 132 (43) | 101 (36) | 84 (40) | 0.28 | 0.52 |

| Positive family history for coronary heart disease | 131 (43) | 111 (39) | 79 (38) | 0.84 | 0.28 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 39 (13) | 31 (11) | 19 (9.1) | 0.53 | 0.21 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 113 (38) | 110 (40) | 94 (45) | 0.23 | 0.08 |

| Previous coronary artery bypass graft | 37 (12) | 18 (6.3) | 11 (5.3) | 0.62 | 0.010 |

| Multivessel disease | 122 (40) | 94 (33) | 63 (30) | 0.54 | 0.026 |

| Clinical success procedure | 241 (79) | 236 (83) | 166 (77) | 0.09 | 0.75 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree