Less Common Malignant Tumors of the Esophagus

Amit Goldberg

The less common malignant tumors of the esophagus share the same common clinical behavior and pathophysiologic features of typical epidermoid carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. The poor outcome for patients with squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma persists despite advances in diagnostic and surgical techniques. Survival rates for patients with rare primary epithelial malignant lesions of the esophagus are equally discouraging. Neither cell type nor degree of histologic differentiation is significant in the prognosis, which is uniformly poor regardless of the treatment received. The uncommon polypoid carcinomas and sarcomas of the esophagus have a somewhat better prognosis when amenable to resection, but spread beyond the esophagus is rapidly fatal. Thus, cancer of this mediastinal organ, however rare the specific tumor may be, is often lethal.

Table 161-1 lists malignant tumors of the esophagus other than typical epidermoid carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. The unusual glandular carcinomas include cylindroma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and adenoacanthoma. Less common epitheliomatous lesions of the esophagus are verrucous carcinoma and polypoid carcinoma. Neuroendocrine carcinoma and melanoma also occur. Of the few remaining primary esophageal malignant tumors, true sarcomas are most notable. Rarely, the esophagus may be involved by metastatic tumor.

Epithelial Tumors

Primary adenocarcinoma of the anatomic esophagus is rare.67 Similar carefully documented studies in the mid-1960s established that primary adenocarcinomas other than those at the gastroesophageal area comprise about 3% of all esophageal carcinomas. However, in more recent years, adenocarcinoma of the esophagus has become the most rapidly increasing solid cancer in America, at a rate of 2% per year. Adenocarcinoma has replaced squamous cell carcinoma as the most common malignant lesion of the esophagus, and its incidence continues to increase in all age groups in the United States.8,9 In 2002, there were about 12,600 deaths due to this malignancy in a single year, while the American Cancer Society projected 14,280 deaths due to this malignancy in 2008 compared to 12,600 deaths in 2002.31 Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction is discussed in detail in Chapter 158.

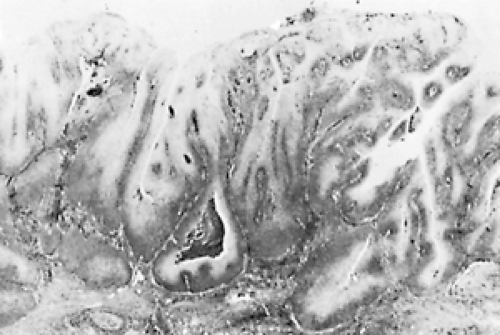

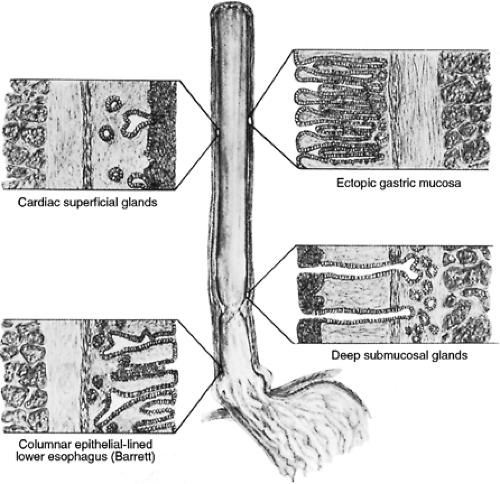

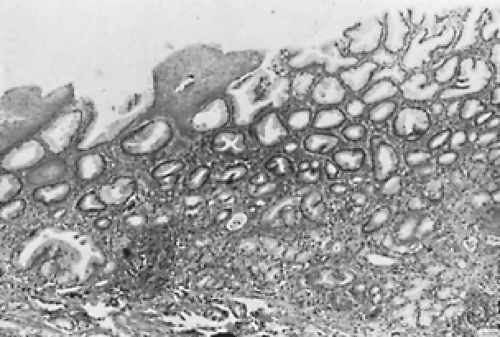

A review of glandular epithelial structures that may be found within the esophagus is essential for understanding the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Only a few sources of columnar epithelium in the esophagus have been recognized (Fig. 161-1). Superficial and deep submucosal glands constitute part of the normal anatomy of the esophagus. Heterotopic islands of aberrant gastric mucosa occur in many organs of the body, including the esophagus. Columnar epithelium-lined lower esophagus (Barrett’s metaplasia) is now thought to be the most common underlying pathologic process that may progress into frank, typical adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Detailed discussions of Barrett’s metaplasia are presented in Chapters 152 and 158. The columnar epithelium in all these locations may become a site of malignant change. In Barrett’s metaplasia, only the intestinal type of columnar epithelial cells are believed to be premalignant.

Unusual Variants of Adenocarcinoma

The superficial esophageal glands arise in tall columnar epithelium noted in the embryo.32 Localization of the superficial glands to the upper and lower ends of the adult esophagus corresponds to the embryonal foci of the columnar epithelium. These mucus-secreting glands occupy an area in the lamina propria and are indistinguishable from the cardiac glands of the stomach. Although these glands might give rise to adenocarcinoma, documented instances are difficult to find.28 Nevertheless, malignant lesions that probably arose from the superficial glands of the esophagus have been described.25,60 A well-illustrated case report by Goldfarb24 removes all doubt that adenocarcinoma can arise from the cardiac submucosal glands of the esophagus. The histologic structure of these lesions is adenocarcinoma “type ordinaire,” as commonly seen in the stomach.

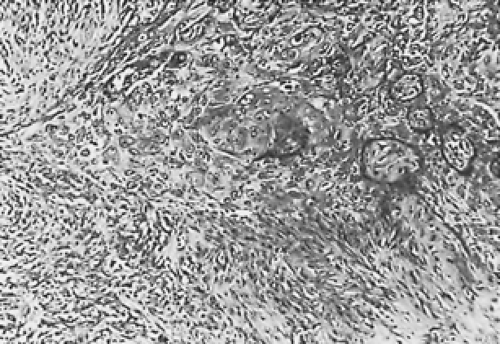

Deep esophageal submucosal glands develop mainly during the postnatal period and are found throughout the length of the esophagus. Columnar cells line the ducts that pierce the muscularis mucosa and extend to the squamous epithelium. Although deep glands secrete mucus, serous cells may be found, which can create an appearance indistinguishable from that of minor salivary glands. Esophageal adenoid cystic carcinoma or cylindroma (Fig. 161-2) is incontrovertible evidence of primary esophageal glandular carcinoma, a tumor well known in the major salivary

glands and oropharyngeal region but with no counterpart in the stomach. In one report, four examples of cylindroma of the esophagus were histologically identical to those found in the salivary glands.4 Rarely, true mucoepidermoid tumors that have a histologic resemblance to lesions of the major salivary glands are observed in the esophagus. These tumors show distinct epidermoid features with histologic evidence of mucus-secreting properties. Such tumors may also arise in the deep submucosal glands of the esophagus. Because of their submucosal origin, these tumors often manifest as intramural masses. Another variant, adenosquamous carcinoma, is similar to mucoepidermoid carcinoma, showing both epidermoid and glandular components.11 Mucoepidermoid carcinomas may demonstrate both in situ and infiltrative components along with pagetoid spread to the surface epithelium, analogous to Paget’s disease of the breast.72

glands and oropharyngeal region but with no counterpart in the stomach. In one report, four examples of cylindroma of the esophagus were histologically identical to those found in the salivary glands.4 Rarely, true mucoepidermoid tumors that have a histologic resemblance to lesions of the major salivary glands are observed in the esophagus. These tumors show distinct epidermoid features with histologic evidence of mucus-secreting properties. Such tumors may also arise in the deep submucosal glands of the esophagus. Because of their submucosal origin, these tumors often manifest as intramural masses. Another variant, adenosquamous carcinoma, is similar to mucoepidermoid carcinoma, showing both epidermoid and glandular components.11 Mucoepidermoid carcinomas may demonstrate both in situ and infiltrative components along with pagetoid spread to the surface epithelium, analogous to Paget’s disease of the breast.72

Table 161-1 Less Common Malignant Tumors of the Esophagus | |

|---|---|

|

Figure 161-1. Sources of columnar epithelium in the esophagus recognized in the origin of primary esophageal adenocarcinoma. |

Figure 161-2. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the esophagus. (From Sobin LH. Histologic Typing of Gastric and Oesophageal Tumours. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1977. With permission.) |

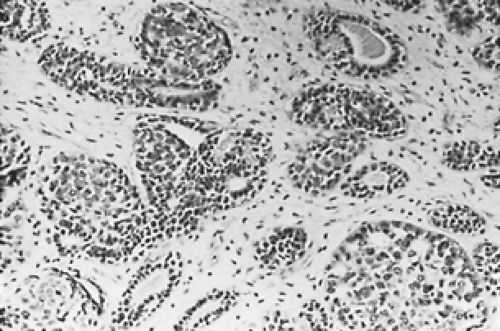

Figure 161-3. Gastric heterotopia, upper esophagus. (From Sobin LH. Histologic Typing of Gastric and Oesophageal Tumours. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1977. With permission.) |

Islands of gastric mucosa sometimes replace portions of the squamous lining of the esophagus (Fig. 161-3). These areas of heterotopic epithelium usually consist of cardiac glands, but they may contain parietal cells. In 7.8% of 1,000 consecutive pediatric autopsies, the heterotopic tissue was found more often in the upper one third of the esophagus.55 Carrie12 was the first to report an example of adenocarcinoma arising from a patch of ectopic gastric epithelium; this source of origin is now established. In situ malignant changes can be found in remnants of heterotopic epithelium, and the tumor is morphologically indistinguishable from gastric carcinoma. A variant of adenocarcinoma displays a concomitant squamous metaplastic element and has been designated adenoacanthoma. The lesion is a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma with groups of squamous cells surrounded by glandular tumor. Distinct from these tumors is the squamous cell carcinoma with pseudoglandular degeneration characterized by lack of mucus secretion and the rare composite adenosquamous malignancy with aggressive glandular and epidermoid elements. It has been suggested that metaplasia of esophageal adenocarcinoma forms hormonally active choriocarcinoma.44 This tumor is rare; it may be a giant cell variant of adenocarcinoma that is attempting trophoblastic differentiation.

Treatment

Surgical resection has been the mainstay of treatment for these unusual variants of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Extensive infiltration of the wall and lymphatics is common; therefore frozen-section examination of the proximal margin is advisable. Radiation therapy along with chemotherapy may result in a gratifying clinical response in some patients. Only surgical excision permits survival of 5 years or more. Histologic type is not an independent predictor of survival in patients undergoing curative resection for carcinoma of the esophagus and the gastroesophageal junction.36 Outcome is most strongly influenced by the extent of disease, defined by TNM staging.

Prognosis

The prognosis for these variants of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is uniformly poor. As in the typical adenocarcinoma, mucoepidermoid tumors of the esophagus show a high degree of malignancy. They are extensively invasive, and metastases are generally present. The relatively benign course of adenocystic carcinomas found in other areas is not applicable to esophageal lesions.46 The latter generally demonstrate extensive intramural spread, and distant metastases are frequent. Such tumors should be treated in the same manner as squamous cell carcinoma—i.e., by radical surgical excision.2

Unusual Variants of Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Verrucous Carcinoma

A distinct morphologic variant of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus is verrucous carcinoma. This tumor is a papillary or warty, cauliflower-like epidermoid growth that is well differentiated histologically and shows acanthosis and hyper- keratosis (Fig. 161-4). Verrucous squamous carcinoma is found most frequently in the oral cavity. It has also been found on the larynx, glans penis, vulva, endometrium, bladder, and anorectal region and is associated with human papillomavirus (HPV)16 infection. Verrucous carcinoma of the esophagus is rare. Chronic retention of esophageal contents may have contributed to the development of these verrucous lesions. Although leukoplakia is commonly associated with verrucous squamous carcinoma in other sites, such as the oral cavity or penis, it is rarely encountered in the esophagus except in association with achalasia or esophageal diverticulum.

The natural history of verrucous squamous carcinoma in the esophagus, as in other sites, is that of a slow-growing but gradually invasive neoplasm. The relatively low yield from mucosal biopsies frequently demonstrates acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and parakeratosis. The uses of endoscopic ultrasound can provide valuable information in the diagnostic process. The slowly progressing infiltrative tumor characteristically becomes large, but distant metastasis has never been reported. Lymph nodes adjacent to the tumor may become involved by direct extension of the tumor. Diagnosis may be difficult because growth is well differentiated and the biopsy specimen may not be deep enough to demonstrate invasion. It may be difficult to distinguish this tumor from squamous cell papilloma.7 Early recognition of the lesion requires clinical suspicion of this growth,

particularly in the presence of achalasia or esophageal diverticulum.

particularly in the presence of achalasia or esophageal diverticulum.

Verrucous carcinoma of the esophagus, as in other sites, ideally should be treated by en bloc surgical resection; radiation therapy alone is not an advisable form of therapy. Irradiation may cause a tumor to regress, but the treatment may also make the low-grade lesion anaplastic and aggressive.23 Irradiation rarely effects a cure. Because verrucous carcinoma of the esophagus follows the usual growth pattern of this tumor elsewhere in the body, the outlook for these patients should be more favorable than it is for patients with the usual type of epidermoid carcinoma. Nonetheless, most patients in whom verrucous carcinoma of the esophagus has been documented have died as a result of their tumors. The poor prognosis of this esophageal lesion is due to the close proximity to vital mediastinal structures, the technical hazards of esophageal resection, and the frequent delay in diagnosis.47 Thus early recognition, along with a reduction in operative mortality by improved surgical techniques, may result in a better prognosis for these patients.

Polypoid Carcinoma

Polypoid carcinoma with spindle cell sarcomatous features is a rare variant of squamous carcinoma, seen most commonly in the mouth, fauces, and upper respiratory tract and less often in the esophagus. When these tumors are present in the esophagus, they are usually in the middle third. In other areas, these tumors often develop apparently in response to radiation therapy for either benign conditions or typical squamous carcinoma, but this association has not been reported for esophageal lesions. The exophytic esophageal tumors have been termed either carcinosarcoma or pseudosarcoma, based on the degree of intermingling and metastatic potentiality of carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements. Hence, carcinosarcoma is characterized histologically by the presence of intimate mingling of the carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements in the primary tumor; metastatic potential is assigned to either the epithelial or sarcomatous component or both. By contrast, in pseudosarcoma, the carcinomatous element, in situ or invasive, is confined to the surface epithelium near the base of the polyp (Fig. 161-5). Only the carcinomatous component of polypoid pseudosarcoma has been considered to have metastatic potential, but also described are the polypoid esophageal malignancies with all the morphologic features of pseudosarcoma and definite evidence of metastasis of the spindle cell element (Fig. 161-6).40,50 As there are no significant differences in the clinicopathologic features of carcinosarcoma and pseudosarcoma, no important distinction can be made between the two tumors; consequently the unifying term polypoid carcinoma was suggested by Osamura et al.41,50

The idea that the sarcomatous elements of polypoid carcinoma arise from transformation of squamous cells was proposed at the turn of the century, and this viewpoint represents the current consensus. Electron microscopic studies supporting the squamous origin of the sarcomatous cells resolved the controversy. In 1972, the first reported electron microscopic study of a polypoid carcinoma of the esophagus (Fig. 161-7) was described, where many cells exhibited desmosomal attachment to neighboring cells with well-developed junctional complexes including tonofilaments (Fig. 161-8).61 Numerous typical branching tonofibrils were seen in a few cells (Fig. 161-9). Tonofibrils are found only in epithelial cells, predominantly squamous types, and are thought to be related to the process of keratinization. Well-developed, tonofilament-associated desmosomes are also

common in epithelial tumors, especially in those of squamous cell origin; thus it was concluded that the spindle-shaped cells in the polypoid tumor originated from squamous cells.61 Indeed, ultrastructural evidence of the squamous origin of the spindle cell element of polypoid esophageal carcinoma was later found.61 From these findings, it was suggested that the sarcomatous component of the tumor originates from mesenchymal metaplasia of squamous cells and that these metaplastic cells produce collagen. On the basis of immunohistochemical analysis, however, Kimura et al. suggested that the anaplastic cells have a myogenic origin.35

common in epithelial tumors, especially in those of squamous cell origin; thus it was concluded that the spindle-shaped cells in the polypoid tumor originated from squamous cells.61 Indeed, ultrastructural evidence of the squamous origin of the spindle cell element of polypoid esophageal carcinoma was later found.61 From these findings, it was suggested that the sarcomatous component of the tumor originates from mesenchymal metaplasia of squamous cells and that these metaplastic cells produce collagen. On the basis of immunohistochemical analysis, however, Kimura et al. suggested that the anaplastic cells have a myogenic origin.35

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree