INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

If one simply abides by the basic tenants of cancer surgery—(1) optimal exposure of the cancer field, (2) complete resection that includes radial margins, (3) extensive locoregional lymphadenectomy for accurate staging and possible benefit, and (4) ease of reconstruction—left thoracoabdominal esophagectomy with cervical esophagogastric anastomosis still remains relevant today. Morbidity of the approach can be reduced by careful preoperative patient selection, meticulous surgical technique, and early recognition and management of evolving postoperative problems.

Perhaps the greatest utility of the left thoracoabdominal approach arises in the reoperative benign disease setting and for difficult to repair perforations. The wide exposure of the pathology is an advantage for these complex operations. The more recent practice of placing synthetic or biosynthetic mesh to repair large hiatal hernias has created difficulty in sparing the esophagus when reoperations are indicated, and for cases where there has been mesh erosion into the esophagus itself, there is no safer exposure for esophagectomy than the left thoracoabdominal approach. Moreover, when salvage of the esophagus is attempted following a distal esophageal perforation, a left thoracotomy incision can be extended to a thoracoabdominal approach for perforations straddling the hiatus to ensure an adequate primary repair.

Contraindications to a left thoracoabdominal approach are few, but clearly, prior left thoracotomy (for lung resection or empyema) would make this exposure more challenging. Repair of the radial diaphragmatic incision is, in part, dependent upon a normally compliant diaphragm. Any prior left-sided operation can compromise this and complicate diaphragm repair during closure. Candidates for this approach should also be able to tolerate single-lung ventilation, as this greatly enhances the exposure.

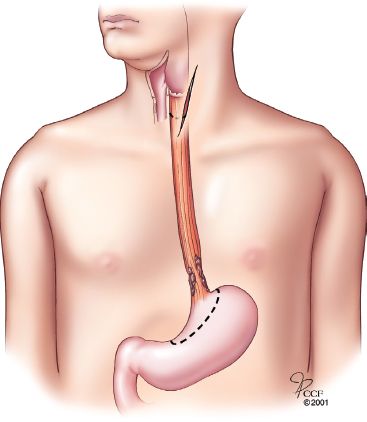

The left thoracoabdominal/left neck approach for esophagectomy is principally a cancer operation (Fig. 23.1) though given the explosive increase in the number hiatal hernia operations performed and their failure rates, it should be considered an important approach for reoperative GEJ surgery. Moreover, for the morbidly obese patient with resectable esophageal cancer, left thoracoabdominal/left neck approach may be technically easier than one requiring laparotomy. Due to the location of the aortic arch, a high left-sided intrathoracic anastomosis cannot be created, as in the Ivor Lewis approach. Consequently, a cervical anastomosis is favored for this technique. Of course, when utilized during repair of esophageal perforation, though no anastomosis will be required, the exposure allows for access for G-tube and J-tube placement.

A left thoracoabdominal/left neck approach for distal esophageal and GEJ adenocarcinoma provides excellent exposure to the tumor bed, allows en bloc resection of regional lymph nodes (N1) and celiac trunk disease (M1A), and permits the entire procedure to be completed with a single sterile preparation and draping. In addition, it affords the surgeon the opportunity to identify peritoneal carcinomatosis and unresectable abdominal disease prior to a commitment to extension of the incision into the left thorax. Finally, significant splenic capsular injury is extremely rare because of the superior access to the short gastric arcade.

Figure 23.1 Operative plan for resection of adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus/gastroesophageal junction with cervical anastomosis.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Because the left thoracoabdominal/left neck procedure is performed infrequently, the orientation of abdominal, thoracic, and cervical structures is less familiar to the surgeon, and an appreciation of the anatomic relationships from the left lateral view must be gained. Structures close or to the right of the midline (i.e., duodenum and thoracic duct) are more difficult to access. Protracted ipsilateral lung collapse may be required to complete the mediastinotomy (for cancer operations). Of importance is the morbidity associated with division of the costal arch and circumferential dissection of the left diaphragm. This morbidity can be significant, and accordingly, specific attention to incision closure at the conclusion of the case is warranted.

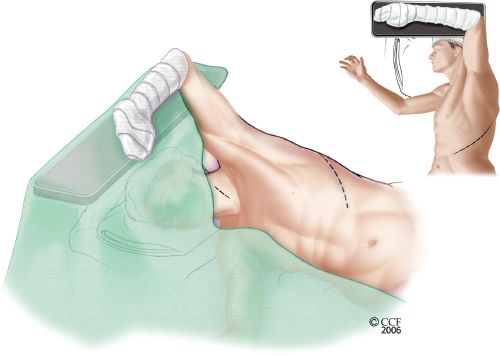

Given that the appropriate assessment of surgical candidacy has taken place, all patients undergo a standard bowel preparation the day before surgery. Epidural analgesia is favored. Standard support lines include: Left-sided double lumen endotracheal tube, nasogastric tube, right internal jugular central venous access, right radial arterial line, and bladder catheter. Patients are positioned in a modified right lateral decubitus position with the abdomen and pelvis rotated back (cork-screwed) toward the table (Fig. 23.2). The sterile prep is extended beyond the midline anteriorly from neck to groin, and posteriorly, to the spine. Regardless of intention of the procedure (benign or malignant indication), the entire left arm is included within the field as is the left neck to allow for possible left neck anastomosis. Until cervical exposure is needed during the case, the left arm is draped across the patient’s body and supported on an arm board. Important musculoskeletal landmarks are the left sternocleidomastoid muscle, scapular tip, costal margin, umbilicus, and anterior iliac spine.

Figure 23.2 Patient position for left thoracoabdominal and neck incisions. The patient’s pelvis is rotated slightly back toward the table to allow better exposure of the abdomen. The left arm is draped within the sterile field and can be repositioned throughout the operation.

SURGERY

SURGERY

Thoracoabdominal Incision

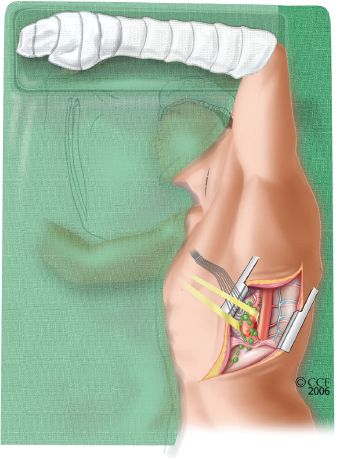

The thoracoabdominal incision generally extends from two fingerbreadths below the scapula tip along the seventh interspace, across the costal margin, and obliquely toward the umbilicus (Fig. 23.3). The oblique abdominal incision, beginning at the costal arch, is made first. External and internal oblique muscles are divided, and the lateral aspect of the rectus muscle and sheath are incised. The left inferior epigastric vascular pedicle is seldom encountered and usually borders the most medial extent of the abdominal incision. Manual palpation of abdominal viscera is used to determine resectability for cancer cases. Specifically, peritoneal carcinomatosis, as well as liver, porta hepatis, duodenum, pancreatic, and gross celiac involvement would end the procedure after an enteral feeding access (J-tube) was placed. If no contraindications to proceeding are encountered, the incision is extended posteriorly and superiorly across the costal margin and along the seventh interspace toward the scapular tip. Lower slips of serratus muscle are generally divided in the direction of their fibers, and the anterior aspect of the latissimus dorsi muscle is incised depending upon the posterior and superior extent of the incision.

To connect the thoracotomy and oblique laparotomy, the costal margin and the diaphragm must be divided. The costal arch is cut sharply, usually between the seventh and eighth ribs. Beginning at this location, the diaphragm is circumferentially divided posteriorly for 8 to 10 cm. A 2-cm margin of diaphragm should be left attached to the chest wall for diaphragm closure at the conclusion of the case. The ribs are distracted in the standard fashion, and a standard abdominal retractor is used. The GEJ should be in the center of the operative field.

Mobilization of the proximal stomach is much easier, since the short gastric arcade is more superficial and approached laterally. For cancer operations, an abdominal lymphadenectomy is far easier to complete (Fig. 23.4). Mobilization of the duodenum (Kocher maneuver) and gastric conduit drainage (pyloromyotomy or pyloroplasty) will initially seem more awkward because of the unfamiliarity with the exposure, but can, nonetheless, be fully completed.

Figure 23.3 Lateral view of the completed thoracoabdominal incision. The inferior aspect of the incision is opened first, and a thorough assessment of the abdominal cavity is undertaken. If advanced disease is not discovered, the incision is extended upward in a posterior-lateral fashion, and the costal margin is divided.