Left-Sided Pulmonary Resections

Larry R. Kaiser

INTRODUCTION TO LEFT-SIDED PULMONARY RESECTIONS

Left-sided resections have a number of unique features distinct from those carried out on the right. The aortic arch is a left-sided structure and its position relative to the pulmonary artery and the left main bronchus is the major defining feature of resections on this side. Access to the proximal left main bronchus and carina is limited because of the aortic arch. Thus the left paratracheal region, a lymph node-bearing area, is difficult to access at thoracotomy. There is no well-defined area where a lymph node dissection is carried out as on the right side. Lymph nodes are dissected from the aortopulmonary window and the subcarinal space and, at times, from the paratracheal area.

Access to the most proximal aspect of the left main pulmonary artery, literally at the level of the pulmonary artery bifurcation, may be gained by dividing the ligamentum arteriosum. The left recurrent laryngeal nerve is highly vulnerable to injury because of its position in relation to the inferior aspect of the aortic arch. This nerve originates from the vagus nerve as it traverses the aortic arch and then “recurs” around the ligamentum arteriosum. Any dissection in the aortopulmonary window places the left recurrent laryngeal nerve at risk of injury.

The left main bronchus also varies significantly from the right. On the left there is a long segment of main stem bronchus prior to the bifurcation of the lobar bronchi as opposed to the right where the right upper lobe bronchus originates within 2 cm of the carina. Sleeve resection of either the upper or lower lobe is certainly feasible though left-sided sleeve resections account for only a minority of these resections in any series.

The lingular segment is analogous to the middle lobe in that it has separate pulmonary arterial supply and venous drainage as well as a distinct bronchus. Lingular segmentectomy was one of the first segmental resections described likely because of its well-defined, discrete bronchovascular anatomy.

Contralateral mediastinal lymph node involvement is much more common with left-sided lesions particularly lesions of the left lower lobe. For that reason, mediastinoscopy or other pathologic staging of the mediastinum is particularly important when assessing lesions of the left lower lobe.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

SURGICAL TECHNIQUELeft Upper Lobectomy

In the realm of pulmonary resections the left upper lobectomy is, perhaps, the most technically challenging. The location of the pulmonary artery in relation to the aorta and the branching pattern of the left pulmonary artery contribute to the technical difficulties. There are a number of potential pitfalls that must be avoided in order to safely complete a left upper lobectomy. Lymphatics from the left upper lobe commonly drain to lymph nodes in the aortopulmonary window (level 5) or para-aortic location (level 6), and these lymph nodes must be removed in order to obtain complete staging information. Despite the classification of these nodal locations as mediastinal (N2), involvement of these lymph nodes with tumor in the absence of other nodal disease is associated with a better prognosis than N2 disease in any other location. Survival with isolated involved level 5 or 6 lymph nodes approximates that of patients who have only N1 lymph node involvement (approximately 40% at 5 years) as long as a complete resection is able to be performed. Access to the superior mediastinum is difficult from the left side because of the location of the aortic arch in relation to the left main bronchus and tracheobronchial angle. For this reason, mediastinoscopy is extremely useful for left-sided lesions even without enlarged lymph nodes present on the CT scan since it allows accurate sampling of the paratracheal area in a manner that is significantly simpler than trying to access this area during thoracotomy. Needle aspiration of left paratracheal and tracheobronchial angle lymph nodes with the aid of endoscopic bronchial ultrasound (EBUS) guidance in some hands may provide equivalent staging information.

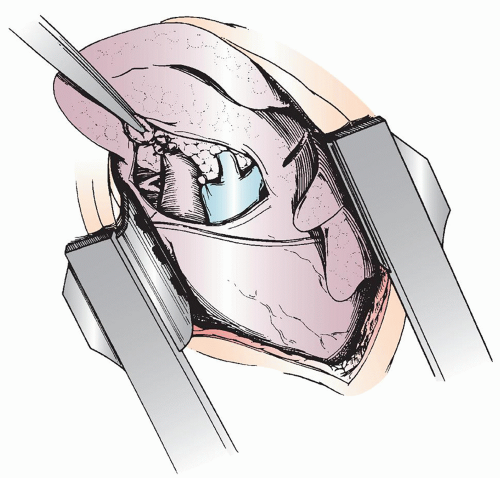

Left upper lobectomy is begun by incising the hilar pleura anteriorly and superiorly with the lobe retracted posteriorly. The pulmonary artery emerges from beneath the aortic arch and is located superior and posterolateral to the superior pulmonary vein. The apical segmental branch of the superior pulmonary vein may cross the artery partly obscuring the apical-posterior segmental trunk of the pulmonary artery necessitating division of the venous branch first (Fig. 5.1). The appropriate plane of dissection on the pulmonary artery is entered proximal to the takeoff of the first branch and careful circumferential dissection is carried out. The left main pulmonary artery is safely encircled with the index finger and a blunt-tipped C-clamp is directed toward the encircled finger to allow an umbilical tape to be passed around the vessel. A Rumel tourniquet is placed but not snared to allow the main pulmonary artery to be occluded should it prove necessary. The superior pulmonary vein is dissected and encircled taking care to include the lingular branch. The vein may be doubly ligated or stapled with a vascular stapler and divided. It is both safe and expeditious to employ vascular staplers to ligate and divide both pulmonary veins and arteries. Parallel rows of staples are placed and the vessel is divided. Alternatively, the endoscopic vascular stapler that cuts between parallel rows each with three layers of staples may also be used.

The apical-posterior segmental branch of the pulmonary artery is a short, broad vessel that may be easily avulsed or torn if too much traction is applied when

retracting the lobe (Fig. 5.1). This is a dreaded complication of left upper lobectomy, which may force a pneumonectomy depending on the extent of the injury. If proximal control of the artery has not been secured, as discussed above, there exists a possibility for a particularly disastrous complication. Trying to get around the left main pulmonary artery in order to place a clamp on the vessel is extremely difficult when at the same time it is necessary to staunch the ongoing hemorrhage from the injury to the artery. Often a significant amount of blood is lost during this maneuver. One should avoid the temptation to wildly try to place a clamp on the vessel. Without encircling the vessel this results in, at best, only partial occlusion and, at worst, further injury to the vessel. Proximal extension of a tear in this portion of the pulmonary artery may result in an irreversible situation with the patient dying from exsanguination. If an injury to the artery occurs and proximal control has not been obtained, one should gently occlude the rent with a finger and assess the situation. It is difficult at best to attempt to suture the pulmonary artery without first gaining proximal control. Attempts to place sutures in the artery under these conditions may result in further injury to the artery as the torrential bleeding does not allow enough visualization to accurately place the sutures. It may be best to open the pericardium to secure additional length of the artery and encircle the artery within the pericardium for proximal control while maintaining the digital pressure on the arterial rent. Once proximal control is achieved, the branch is completely divided and the artery repaired with 5-0 or 6-0 monofilament, nonabsorbable sutures. Rather than avulsion of the apical-posterior arterial branch, a more common traction injury is a hematoma in the vessel from an intimal tear. The intima is the structure responsible for the integrity of the pulmonary artery; so this has the potential to be a disastrous situation. Proximal control should be obtained and the branch vessel ligated preferably proximal to the intimal tear. Placing a ligature at the area of the tear may result in complete avulsion of the branch when the knot is placed. As noted, it is best to recognize that this arterial branch presents special problems and avoiding problems with the pulmonary artery is far better and simpler than having to repair the artery no matter how good you may be at getting out of trouble.

retracting the lobe (Fig. 5.1). This is a dreaded complication of left upper lobectomy, which may force a pneumonectomy depending on the extent of the injury. If proximal control of the artery has not been secured, as discussed above, there exists a possibility for a particularly disastrous complication. Trying to get around the left main pulmonary artery in order to place a clamp on the vessel is extremely difficult when at the same time it is necessary to staunch the ongoing hemorrhage from the injury to the artery. Often a significant amount of blood is lost during this maneuver. One should avoid the temptation to wildly try to place a clamp on the vessel. Without encircling the vessel this results in, at best, only partial occlusion and, at worst, further injury to the vessel. Proximal extension of a tear in this portion of the pulmonary artery may result in an irreversible situation with the patient dying from exsanguination. If an injury to the artery occurs and proximal control has not been obtained, one should gently occlude the rent with a finger and assess the situation. It is difficult at best to attempt to suture the pulmonary artery without first gaining proximal control. Attempts to place sutures in the artery under these conditions may result in further injury to the artery as the torrential bleeding does not allow enough visualization to accurately place the sutures. It may be best to open the pericardium to secure additional length of the artery and encircle the artery within the pericardium for proximal control while maintaining the digital pressure on the arterial rent. Once proximal control is achieved, the branch is completely divided and the artery repaired with 5-0 or 6-0 monofilament, nonabsorbable sutures. Rather than avulsion of the apical-posterior arterial branch, a more common traction injury is a hematoma in the vessel from an intimal tear. The intima is the structure responsible for the integrity of the pulmonary artery; so this has the potential to be a disastrous situation. Proximal control should be obtained and the branch vessel ligated preferably proximal to the intimal tear. Placing a ligature at the area of the tear may result in complete avulsion of the branch when the knot is placed. As noted, it is best to recognize that this arterial branch presents special problems and avoiding problems with the pulmonary artery is far better and simpler than having to repair the artery no matter how good you may be at getting out of trouble.

Dissection on the artery continues distally following the artery toward and into the fissure. The left main pulmonary artery resides in an epibronchial location relative to the left main bronchus (Fig. 5.2). As the fissure is entered, the anterior segmental arterial branch to the upper lobe is encountered just proximal and opposite to the origin of the superior segmental branch to the lower lobe. Once the superior segmental branch is identified, the posterior portion of the fissure may be completed with a stapler. The anterior segmental branch is divided between silk ligatures (Fig. 5.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree