INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Subglottic laryngotracheal stenosis is caused by a variety of processes including: Intubation, cricothyroidotomy, trauma, burns, and Wegener granulomatosis. However, idiopathic laryngotracheal stenosis (ILTS) has been the most common indication for laryngotracheal resection and reconstruction in case series over the past 25 years. In general, with the exception of Wegener granulomatosis, all of the above conditions may be cured with a single-stage resection and reconstruction of the airway, as long the stenosis does not extend all the way to the vocal cords. In addition, tumors, most commonly invasive thyroid carcinomas, may extend across the laryngotracheal junction and require partial resection of the cricoid to obtain negative margins.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

A careful history and physical examination should be performed on every patient. ILTS is a diagnosis of exclusion. Other causes of tracheal stenosis are usually readily identifiable from history. However, an anticytoplasmic nuclear antigen (ANCA) panel should be drawn on every patient to rule out collagen vascular diseases such as Wegener granulomatosis. These may not respond to resection and reconstruction and should be managed with serial dilation, local steroid injection, or systemic therapy.

Imaging should be obtained to help determine the anatomy and extent of the stenosis. Either conventional tracheal radiographs with PA, oblique, and lateral views of the neck or a thin slice spiral CT of the neck may suffice. MRI may also be obtained in select circumstances but does not ordinarily provide information different than CT.

For patients with alterations of their voice or a traumatic etiology suggesting vocal cord dysfunction or glottic inadequacy, otolaryngology consultation should be obtained prior to any elective procedures on the more distal airway. It is advantageous for these problems to be corrected first to allow for safe extubation at the end of any subglottic resection and reconstruction. Patients should be weaned off systemic steroids prior to any planned resection, as their use is associated with an increased risk of anastomotic complication. Those with symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux should have this addressed medically, or surgically if necessary, to protect the anastomosis in the postoperative period.

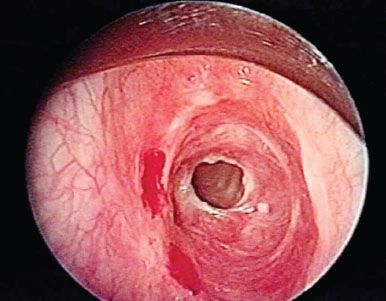

Figure 36.1 Rigid bronchoscopic view of a patient with subglottic stenosis

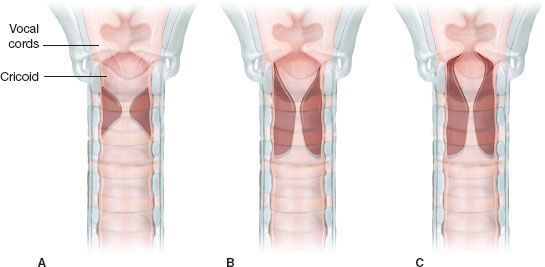

Finally, the patient should undergo endoscopic examination of the airway. This may be done using either flexible or rigid bronchoscopes though a rigid bronchoscope should be readily available in the event that dilation of the stricture is needed to obtain an adequate airway. Care should be taken to assess the length and degree of stenosis, as well as its relationship to the vocal cords (Fig. 36.1). General anesthesia with a laryngeal mask airway may optimize visualization of the proximal airway and vocal cords. If the stenosis abuts the vocal cords or vocal cord mobility is impaired, it is not possible to perform a single-stage correction (Fig. 36.2). The patient’s airway should be temporized with dilation, and they should be referred to an otolaryngologist.

Tracheostomy should be avoided, if possible, as its presence dictates a longer tracheal resection at the definitive operation. It is preferable to temporize the airway with dilation instead. The authors’ preference is to use Jackson dilators and graduated rigid bronchoscopes. Balloon dilation is an acceptable alternative but may prove difficult with more proximal lesions. Lasers and cryotherapy should be avoided as it is difficult to control the depth of injury and subsequent scarring and granulation may complicate final reconstruction.

If active inflammation is present, resection and reconstruction should be delayed until it subsides. Twice a day saline nebulizers and short courses of antibiotics may be useful for controlling localized tracheitis, preoperatively. If dilation is performed during evaluation, a short course of steroids (dexamethasone 10 mg IV during the procedure, followed by 4 mg IV every 6 hours for 24 hours) is often prudent to prevent edema.

Figure 36.2 Diagrams of the typical distribution of idiopathic laryngotracheal stenosis. A: Lesion confined principally to the upper trachea, but which usually impinges on the low subglottic larynx at cricoid level. B: Lesion commencing in the subglottic larynx with narrowing of the immediate subglottic space, which however, leaves an “atrium” beneath the cords. The maximum stenosis is at cricotracheal level. C: More marked stenosis immediately below the vocal cords with little space for anastomosis even at that level.

SURGERY

SURGERY

Anesthesia

An anesthesia team experienced in airway surgery is critical to a safe and efficient operation. In general, the patient is induced with a short-acting intravenous agent with the surgical team and rigid bronchoscopy immediately available as positive pressure ventilation may convert a partial to a complete obstruction. Jackson dilators and rigid bronchoscopy are then used to dilate the stenosis until it is large enough to accept a 5 or 5.5 endotracheal tube. The patient is then intubated. Anesthesia may be maintained using inhalation agents, however, total intravenous anesthesia with short-acting agents such as propofol and remifentanil allow for continuous anesthesia when inhalation is interrupted by the surgical team and early extubation at the conclusion of the case.

Positioning

After intubation, the patient is maintained in a supine position with the head of the bed gently elevated. A thyroid bag placed beneath the patient’s shoulder is inflated to extend the neck 20 degrees. The arms are left at the patient’s sides. The patient’s neck and chest are prepped and draped. Cross-field ventilation equipment is prepared for use.

Technique

A low collar incision one fingerbreadth below the cricoid is performed and carried through the platysma. Subplastysmal flaps are then elevated to the superior margin of the larynx, inferiorly to the sternal notch, and laterally to the sternocleidomastoid muscles. Gelpi retractors are placed to spread the skin. The strap muscles are then split in the midline and the thyroid isthmus divided and suture ligated. The thyroid sutures are left in place for traction. A Weitlaner retractor is used to retract the strap muscles laterally. The pretracheal plane is then entered and developed to the carina using blunt dissection similar to mediastinoscopy.

Circumferential dissection of the trachea is then commenced at the lower aspect of the lesion. This should be done sharply and directly on the trachea to avoid injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerves. No effort is made to dissect the nerves out. The trachea is then divided at the distal aspect of the stricture. It should be circumferentially mobilized no more than 1 to 2 cm from the cut edge to prevent devascularization. Resection should be conservative until the full extent of cricoid and tracheal involvement is assessed. In addition, trachea may be excised serially until the distal margin is free of disease. 2-0 vicryl traction sutures are placed on either lateral aspect of the distal trachea at least two rings from the cut edge to allow for stretching of the trachea upon reconstruction. The endotracheal tube may be then withdrawn and cross-field ventilation initiated when convenient.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree