We describe a 41-year-old man with De Mosier’s syndrome who presented with exercise intolerance and dyspnea on exertion caused by a giant hiatal hernia compressing the heart with relief by surgical treatment.

Case Description

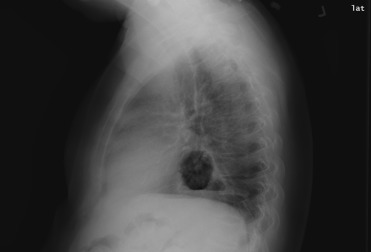

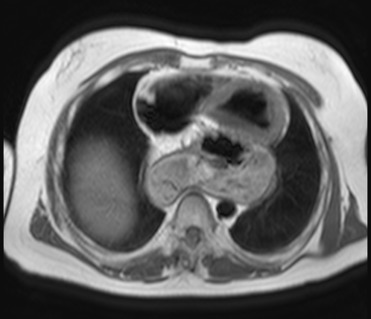

A 41-year-old man was referred because of bradycardia (35 to 40 beats/min), fatigue marked limitation in ability to walk more than one block or bowl. He had no history of dyspepsia, vomiting, or reflux. He had known De Mosier’s syndrome (endocrine deficiency, mental retardation, blindness, and seizure disorder). On examination, he appeared to be in no distress. The blood pressure was 110/75 mm Hg, heart rate 59 beats/min, respirations 18 breaths per minute. On exercise stress test (Bruce protocol), he exercised for 3:28 minutes achieving 5 metabolic equivalent of task. He was able to reach a maximum heart rate of 149 beats/min. No ischemia was noted on electrocardiogram. Twenty-four–hour Holter monitor showed no bradycardic events. A 2-dimensional echocardiogram revealed normal left ventricular systolic function. A mass was noted extrinsically compressing the left atrium. A chest x-ray ( Figure 1 ) showed a retrocardiac gastric bubble, and magnetic resonance imaging confirmed a large hiatal hernia compressing both left atrium and ventricle ( Figure 2 ). He underwent successful hiatal hernia repair and gastrostomy. His cardiac symptoms completely resolved, and his dyspnea and fatigue markedly improved and stamina returned to baseline.

Discussion

Hiatal hernias are defined as the herniation of components of the abdominal cavity through the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm. The type 1, or sliding hernia, constitutes 95% of all hiatal hernias. Most patients with type 1 hernias are asymptomatic but may have gastroesophageal reflux disease. Giant hernias are usually asymptomatic but can manifest with nonspecific abdominal symptoms, exercise intolerance, and dyspnea. Rarely, gastric volvulus, hemorrhage, and respiratory distress may occur.

Although dyspnea can be due to reflux-mediated lung fibrosis or compression, it can also be due to mass effect on the nearby cardiac structures as seen in our patient. Impingement of the left atrium, pulmonary veins, and coronary sinus can result in reduced cardiac output. A key diagnostic clue, although not present in our patient, is postprandial syncope resulting from a decrease in left atrial volumes after meals.

Surgical repair of large hiatal hernia has been proved to significantly relieve symptoms, as seen in our patient. However, recurrence has been documented and long-term follow-up should be considered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree