11

CHAPTER

![]()

Large and Small Airway Diseases

This chapter includes diseases in which the predominant pathologic changes involve bronchi and bronchioles. Emphasis is on those entities that may be encountered in biopsy or surgical specimens either as the primary diagnosis or as a component of other lesions.

TOPICS

Large Airway Diseases

Large Airway Diseases

Asthma

Asthma

Bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis

Mucoid Impaction of Bronchi (MIB)

Mucoid Impaction of Bronchi (MIB)

Tracheobronchial Amyloidosis

Tracheobronchial Amyloidosis

Tracheobronchopathia Osteoplastica (TO)

Tracheobronchopathia Osteoplastica (TO)

Small Airway Diseases

Small Airway Diseases

Respiratory Bronchiolitis (RB)

Respiratory Bronchiolitis (RB)

Follicular Bronchiolitis

Follicular Bronchiolitis

Diffuse Panbronchiolitis

Diffuse Panbronchiolitis

Acute Cellular Bronchiolitis

Acute Cellular Bronchiolitis

Constrictive Bronchiolitis Obliterans (CBO)

Constrictive Bronchiolitis Obliterans (CBO)

Diffuse Idiopathic Neuroendocrine Cell Hyperplasia (DIPNECH)

Diffuse Idiopathic Neuroendocrine Cell Hyperplasia (DIPNECH)

ASTHMA

Although biopsies are not used to diagnose asthma, changes of asthma are occasional incidental findings in surgical specimens removed for tumors and other lesions as well as in bronchial biopsy or transbronchial specimens. Changes of asthma are also commonly associated with other diseases in which biopsies may be taken, such as eosinophilic pneumonia (Chapter 4), Churg–Strauss syndrome (Chapter 6), mucoid impaction of bronchi (MIB), and allergic bronchopulmonary fungal disease (see subsequent section, “Allergic Bronchopulmonary Fungal Disease”), for example, and its recognition may facilitate diagnosis of the underlying disease.

Histologic Features

Goblet cell hyperplasia in bronchial epithelium often with intraluminal mucinous exudate

Goblet cell hyperplasia in bronchial epithelium often with intraluminal mucinous exudate

Thickened epithelial basement membrane and smooth muscle hyperplasia in bronchial wall

Thickened epithelial basement membrane and smooth muscle hyperplasia in bronchial wall

Chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate with eosinophils

Chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate with eosinophils

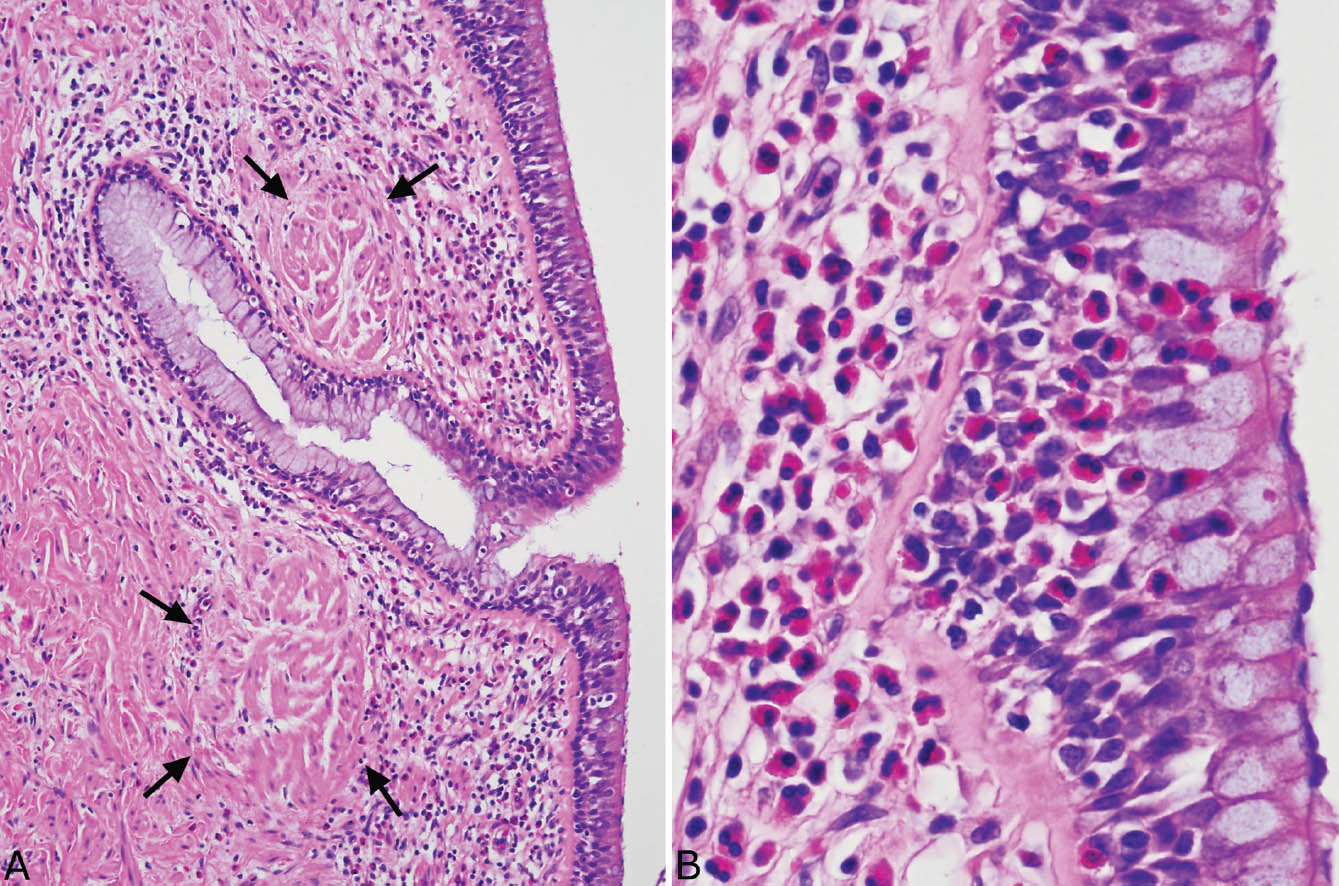

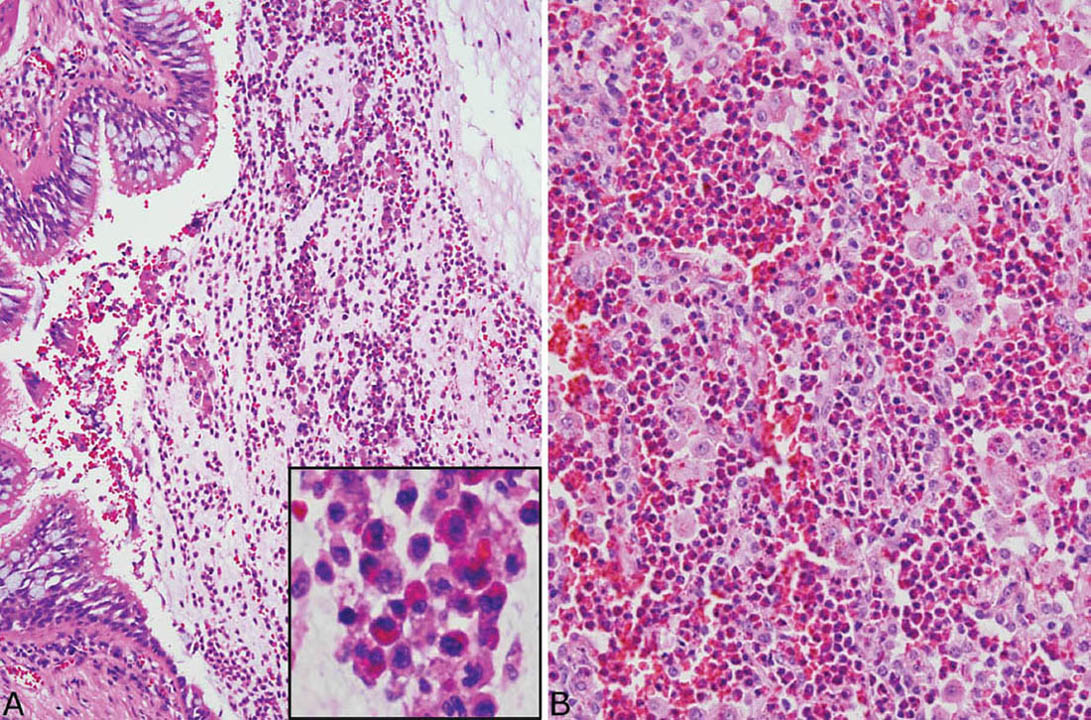

Typical changes of asthma are found within bronchi, whereas more distal bronchioles usually show only mild if any changes. Increased numbers of goblet cells are characteristically present in the bronchial epithelium, and the underlying epithelial basement membrane is thickened (Figure 11.1; see also Figure 11.6A). Hyperplasia of smooth muscle bundles in the bronchial wall is usually a prominent accompanying feature. A variable chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate usually containing numerous eosinophils is present in the bronchial wall, although eosinophils may be inconspicuous or absent if the patient has been treated with corticosteroids. Often a mucinous exudate containing a mixture of sloughed epithelial cells, mononuclear inflammatory cells, eosinophils, and occasional Charcot–Leyden crystals (see subsequent section, “Mucoid Impaction of Bronchi”) may be present within the bronchial lumens.

BRONCHIECTASIS

Bronchiectasis is defined as the permanent dilatation of bronchi accompanied by inflammation in their walls and in surrounding parenchyma. Most cases follow prolonged or recurrent infection, and the pathogenesis is related to a combination of bronchial wall weakening by the inflammatory cell infiltrate and traction from peribronchial fibrosis and scarring.

FIGURE 11.1 Asthma. (A) At low magnification, prominent goblet cell hyperplasia is visible in the bronchial epithelium. The epithelial basement membrane is thickened, and there is marked smooth muscle hyperplasia (arrows) in the wall. A chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate containing numerous eosinophils is also present. (B) At higher magnification, the prominent eosinophil infiltrate is highlighted both in the wall and in the overlying epithelium. Note the accompanying goblet cell hyperplasia and the thickened epithelial basement membrane.

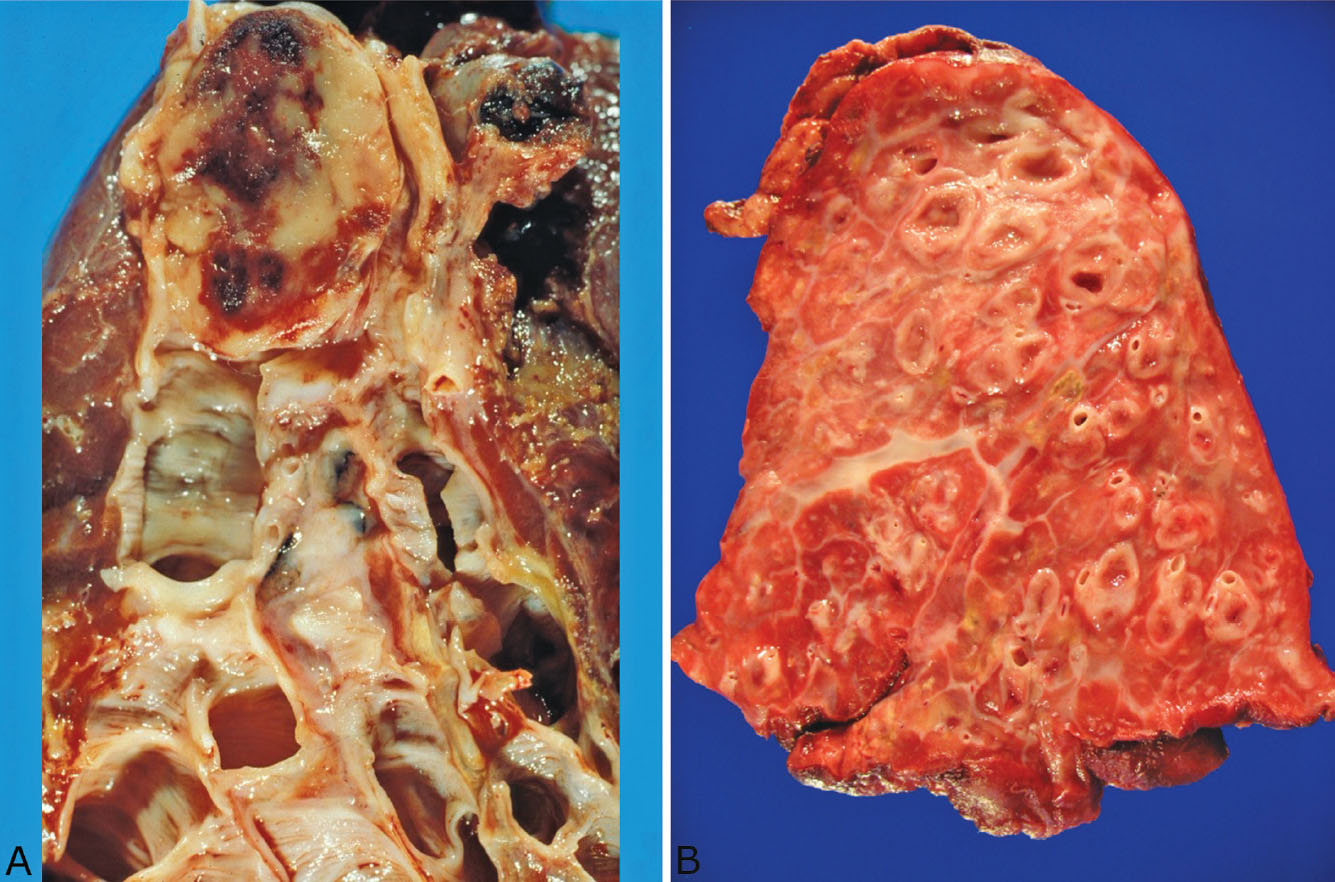

Bronchiectasis may be localized or diffuse. In the past, localized bronchiectasis was most commonly encountered in lobectomy specimens from children or young adults with a history of poorly treated pneumonias (so-called post-inflammatory bronchiectasis; Figure 11.2). Although with the widespread use of antibiotics this complication is now rare, post-inflammatory bronchiectasis is commonly seen in the middle lobe syndrome (see subsequent section, “Middle Lobe Syndrome”). More often, localized bronchiectasis is encountered as an incidental finding distal to bronchial obstruction (so-called post-obstructive bronchiectasis) as may occur with tumors, aspirated foreign bodies, or broncholithiasis, for example (Figure 11.3A). Widespread, diffuse bronchiectasis involving multiple lobes is rare and usually signifies an underlying predisposing disease, most commonly cystic fibrosis (Figure 11.3B). Mucoid impaction of bronchi (MIB) is a unique form of localized bronchiectasis and is discussed in the subsequent section, “Mucoid Impaction of Bronchi.”

The diagnosis of bronchiectasis is based on gross examination revealing dilated bronchi extending almost to the pleural surface, a location in which normal bronchi are not visible grossly. Purulent exudates may be present within the bronchial lumens, and parenchymal scarring may be prominent in surrounding parenchyma. The bronchial mucosa often has a ridged or corrugated appearance. The histologic features are nonspecific and reflect ongoing inflammatory and fibrotic changes.

Histologic Features

Dilated, thin-walled bronchi with damaged or destroyed cartilage, and nonspecific acute and chronic inflammation in their walls and lumens

Dilated, thin-walled bronchi with damaged or destroyed cartilage, and nonspecific acute and chronic inflammation in their walls and lumens

Variable surrounding acute and organizing pneumonia and fibrosis

Variable surrounding acute and organizing pneumonia and fibrosis

MIDDLE LOBE SYNDROME

The middle lobe syndrome refers clinically to chronic opacification usually affecting the right middle lobe and less often the lingula; bronchiectasis is the most common pathologic finding.

FIGURE 11.2 Bronchiectasis. (A) This left lower lobectomy was performed for localized, post-inflammatory bronchiectasis in a young adult. Note the dilated bronchi with surrounding scarring on the right compared to the relatively normal bronchus on the left. (B) A close-up view of bronchiectasis from another case showing the characteristic ridged or corrugated appearance of the bronchial mucosa. Note also the surrounding white scarred parenchyma.

FIGURE 11.3 Bronchiectasis. (A) In this example of localized post-obstructive bronchiectasis, a carcinoid tumor (top) has completely obstructed the proximal bronchus resulting in distal bronchiectasis. (B) This example of diffuse post-inflammatory bronchiectasis is a right pneumonectomy specimen from a 13-year-old boy with cystic fibrosis. The lung was excised to prevent spread of infection to the left lung, which was relatively unaffected.

Histologic Findings

In addition to typical features of bronchiectasis within the airways, acute and chronic inflammation and fibrosis may obliterate most of the surrounding middle lobe or lingular parenchyma. Organizing pneumonia is another common but nonspecific finding. Granulomatous inflammation, including both non-necrotizing and necrotizing, may accompany the other changes, and usually indicates mycobacterial, especially mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) infection (see next section, “Clinical Features”).

Clinical Features

Middle lobe syndrome occurs most often in adults, especially in older women, but also has been reported in children. Poor drainage of secretions inherent to the anatomic location is the likely cause in most cases. Lobectomy is performed in patients with recurrent symptoms uncontrolled by medical therapy. Some cases, especially in elderly women, are caused by MAC infection (see Chapter 8), and are referred to as the Lady Windermere syndrome. Voluntary cough suppression by these patients is thought to contribute to the pathogenesis.

MUCOID IMPACTION OF BRONCHI (MIB)

MIB is a specific form of proximal bronchiectasis. Most cases are encountered in lobectomy specimens, although occasionally a bronchial biopsy will be diagnostic. Many cases are manifestations of allergic bronchopulmonary fungal disease (ABPFD, see subsequent section, “Allergic Bronchopulmonary Fungal Disease”).

Histologic Features

Bronchiectasis with eosinophil infiltrates

Bronchiectasis with eosinophil infiltrates

Allergic mucin often containing fungal hyphae in the lumens of dilated bronchi

Allergic mucin often containing fungal hyphae in the lumens of dilated bronchi

Eosinophilic pneumonia and bronchocentric granulomatosis often present in distal parenchyma

Eosinophilic pneumonia and bronchocentric granulomatosis often present in distal parenchyma

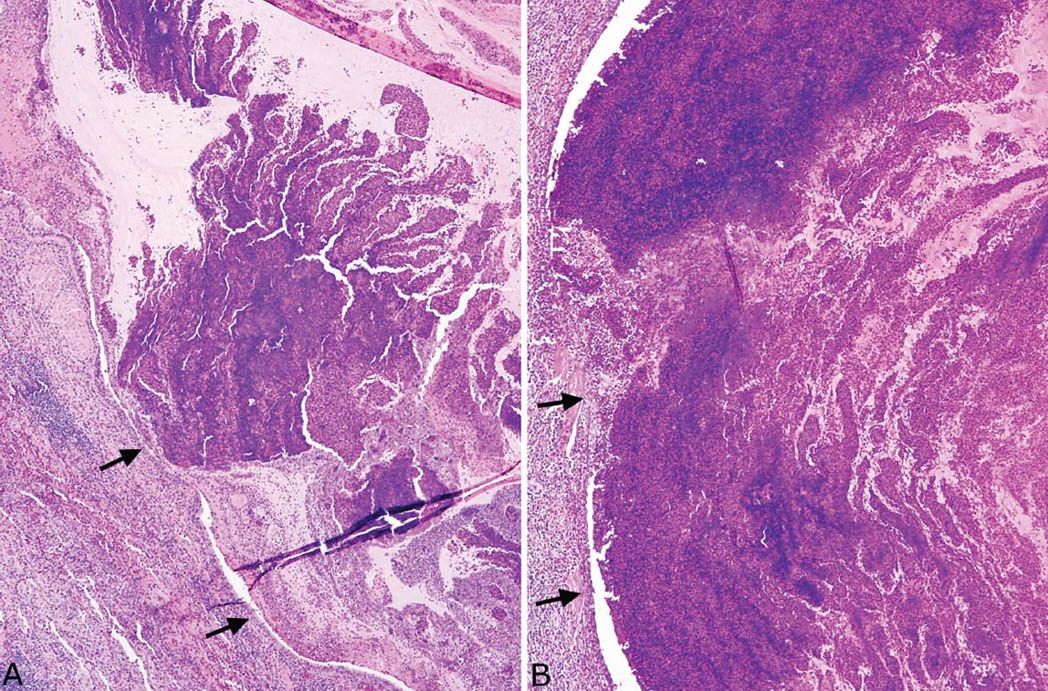

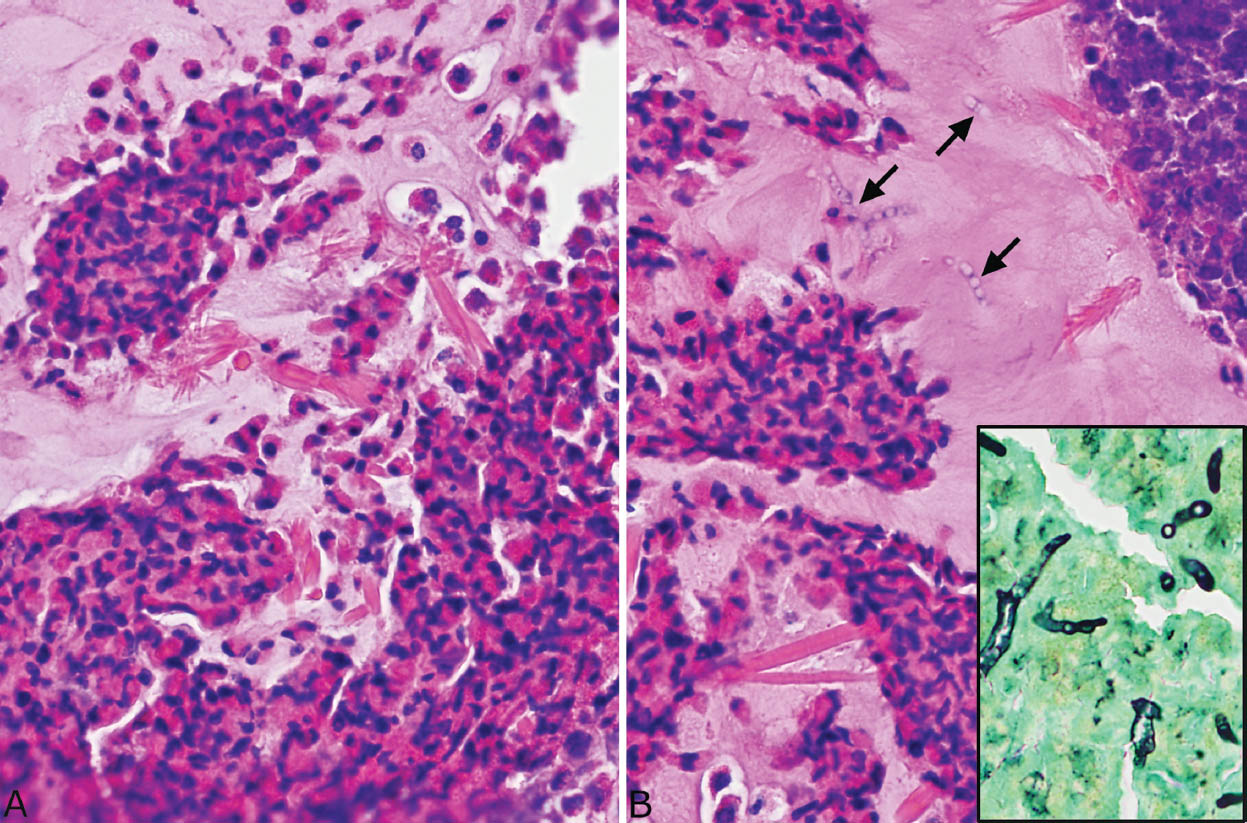

MIB is a specific form of bronchiectasis with typical luminal dilatation and thinned bronchial wall that involves proximal airways. The histologic hallmark is the presence of inspissated mucinous and cellular material that shows features of allergic mucin within the dilated lumens. Allergic mucin is characterized by a striking lamellar appearance at low magnification that is caused by clusters of degenerating cells layered within lightly staining blue-gray to eosinophilic mucin (Figure 11.4). On closer examination, most of the cells are degenerating eosinophils, although lesser numbers of sloughed bronchial epithelial cells, macrophages, and cell debris are also admixed (Figure 11.5). Occasional neutrophils may be present as well, but neutrophils are never numerous. Charcot–Leyden crystals, which are thought to be eosinophil-breakdown products, are always present and are necessary for diagnosis of allergic mucin (Figure 11.5). They are crystalloid structures that vary greatly in size and are best visualized within the mucin between the cell clumps in which they appear bipyramidal in longitudinal section and hexagonal in cross section. In many cases of MIB, scattered fungal hyphae can also be found in the allergic mucin, and their presence is indicative of ABPFD (see subsequent section, “Allergic Bronchopulmonary Fungal Disease”). Occasionally, they can be seen in hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) stained slides, but a Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) stain is usually needed because the hyphae are not numerous (Figure 11.5B). They appear irregularly arranged and fragmented with degenerative features, rather than uniform and organized as in invasive infections.

Eosinophils are a common finding in the parenchyma surrounding MIB and in cases of ABPFD. Small bronchi and some bronchioles may show features of asthma (Figure 11.6A), whereas eosinophilic bronchiolitis with intraluminal eosinophils and a dense peribronchiolar eosinophil infiltrate may be present in others (see Figure 6.25B). Areas of eosinophilic pneumonia (Chapter 4) are common within the adjacent parenchyma as well and are characterized by a mixture of eosinophils and macrophages filling alveolar spaces (Figure 11.6B; see also Figures 4.9, 4.10, and 4.11).

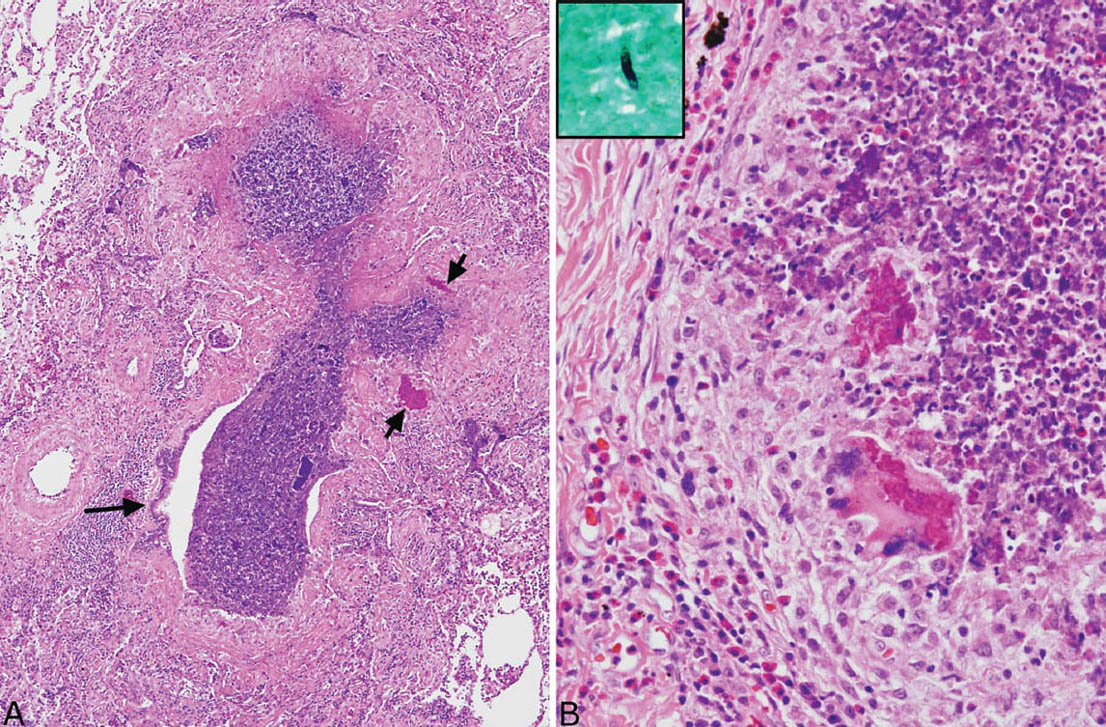

Another common finding distal to MIB is bronchocentric granulomatosis (Figure 11.7; see also Chapter 6, Figures 6.22–6.26). It is a necrotizing granulomatous process that centers upon and destroys bronchioles. Although granulomatous replacement of bronchioles can occur in infections and other granulomatous processes, when present in the context of MIB and eosinophilia, it is highly suggestive of ABPFD, and the finding of fungal hyphae remnants within the intraluminal necrotic debris confirms the diagnosis. One additional curious finding in some cases is clumps of coarsely granular, acellular eosinophilic material often engulfed by foreign-body giant cells present in and around the inflamed bronchioles (Figure 11.7B). The nature of these clumps is uncertain but they may represent degenerated eosinophils from the proximal MIB.

Differential Diagnosis

If the histologic characteristics of allergic mucin are remembered, MIB should not be confused with other forms of bronchial mucus plugging. Specifically, the common post-obstructive bronchiectasis with mucus plugging differs in that the mucus plugs contain mainly acute inflammatory cells and debris with scattered macrophages and bronchial epithelial cells within mucin, but rare, if any, eosinophils. No Charcot–Leyden crystals are seen, and characteristic layering of cells is absent. Plastic bronchitis is a rare entity that may occur in association with infections, bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, cardiac anomalies, or sickle cell disease. Although large intrabronchial plugs grossly similar to the mucus plugs in MIB may occur, the histologic findings resemble post-obstructive plugs, and allergic mucin is absent.

FIGURE 11.4 Mucoid impaction of bronchi. (A) At low magnification, a markedly dilated and inflamed bronchus is appreciated (arrows mark the bronchial epithelium on the left). Note the prominent layered appearance to the cell clusters within the lightly staining mucin that fills the lumen and is characteristic of allergic mucin. A dense eosinophil infiltrate surrounds the dilated bronchus (lower left). (B) In this example, the intraluminal mucinous and cellular exudate appears more solid but retains the characteristic lamellar appearance in areas. The arrows mark the surrounding bronchial epithelium on the left.

FIGURE 11.5 Allergic mucin in MIB. (A) A higher magnification shows the typical clusters of degenerating eosinophils alternating with relatively acellular mucin. Numerous varying-sized Charcot–Leyden crystals are seen within the mucin. Note their bipyramidal shape in longitudinal section and the hexagonal (center) shape in cross section. (B) In this example, scattered fungal hyphae are also seen in the mucin in the H and E stain and confirmed in a GMS stain (inset). Note their degenerative features and haphazard arrangement. GMS, Gomori methenamine silver; H and E, hematoxylin and eosin; MIB, mucoid impaction of bronchi.

FIGURE 11.6 Eosinophil infiltrates in MIB. (A) Changes of asthma are seen in this small bronchus distal to MIB. Note the goblet cell hyperplasia and thickened basement membrane. A mucinous exudate containing numerous eosinophils and macrophages (inset) is present in the lumen, but the lamellar arrangement of MIB is not present. (B) Eosinophilic pneumonia is present in parenchyma adjacent to the MIB in this case. Note the alveolar spaces packed with eosinophils and some macrophages. MIB, mucoid impaction of bronchi.

FIGURE 11.7 Bronchocentric granulomatosis in MIB. (A) The wall of this bronchiole (center) is almost completely replaced by necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with only a small focus of epithelium remaining (long arrow). The lumen is filled with a necrotic cellular exudate. Note the two acellular eosinophilic clumps (short arrows). (B) Higher magnification from another bronchocentric granuloma shows epithelioid histiocytes surrounding the central necrotic cellular exudate. Eosinophils are numerous in the surrounding infiltrate as well as in the necrotic exudate. Note the foreign-body reaction to the granular eosinophilic clumps. The inset is a GMS stain identifying a single fungal hyphal fragment within the necrotic debris, thus confirming ABPFD. ABPFD, allergic bronchopulmonary fungal disease; GMS, Gomori methenamine silver.

Although inspissated mucus containing eosinophils and occasional Charcot–Leyden crystals may be found in small bronchi in cases of otherwise uncomplicated asthma, the layering pattern of eosinophil clumps and the marked bronchial dilatation characteristic of MIB are absent.

Clinical Features

Most patients with MIB are asthmatics. Signs and symptoms of acute pneumonia related to bronchial obstruction are common at presentation, whereas some patients are asymptomatic. Radiographically, V- or Y-shaped densities involving proximal bronchi or an appearance resembling a cluster of grapes often with distal collapse or consolidation may be seen. Rarely, MIB appears as a rounded density suggesting neoplasm radiographically, and such unsuspected cases may be excised.

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Fungal Disease (ABPFD)

ABPFD is a clinical syndrome often manifesting MIB pathologically along with the frequently accompanying features of eosinophilic pneumonia and bronchocentric granulomatosis. It occurs exclusively in asthmatics and is caused by fungal hypersensitivity usually to aspergillus species, especially Aspergillus fumigatus (referred to as allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis—ABPA) or less often to other fungi (hence the more generic term, ABPFD). The diagnosis of ABPFD is usually made clinically based on the presence, in addition to asthma, of blood eosinophilia, lung infiltrates, immediate cutaneous reactivity to aspergillus or other fungi, elevated total serum IgE, precipitating antibodies to aspergillus or other fungi, elevated serum levels of specific IgE and IgG antibodies, and central bronchiectasis. Patients are treated with corticosteroids and sometimes antifungal agents. Establishing the diagnosis is important, especially in clinically unsuspected cases since, if untreated, recurrences are common and may lead to irreversible fibrosis. Additional clinical evaluation for ABPFD, therefore, is indicated in all patients with MIB whether or not fungi are identified histologically.

Helpful Tips—MIB

Always section the inspissated intraluminal mucinous material in bronchiectasis; do not wash out and discard before sectioning.

Always section the inspissated intraluminal mucinous material in bronchiectasis; do not wash out and discard before sectioning.

Do not diagnose allergic mucin and therefore MIB in the absence of Charcot–Leyden crystals.

Do not diagnose allergic mucin and therefore MIB in the absence of Charcot–Leyden crystals.

Always search allergic mucin with GMS for fungal hyphae.

Always search allergic mucin with GMS for fungal hyphae.

ABPFD should be diagnosed when fungal hyphae are identified within allergic mucin of MIB or in associated bronchocentric granulomatosis.

ABPFD should be diagnosed when fungal hyphae are identified within allergic mucin of MIB or in associated bronchocentric granulomatosis.

Additional clinical workup should be suggested to rule out ABPFD in cases of MIB containing allergic mucin but no identifiable fungi.

Additional clinical workup should be suggested to rule out ABPFD in cases of MIB containing allergic mucin but no identifiable fungi.

Findings identical to MIB with allergic mucin may occur in the paranasal sinuses, and, analogous to the lung, usually indicate allergic fungal sinusitis.

Findings identical to MIB with allergic mucin may occur in the paranasal sinuses, and, analogous to the lung, usually indicate allergic fungal sinusitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree