INDICATIONS

There are three schools of thought regarding the indications for a partial fundoplication: (1) That they are unneeded, since the 360-degree Nissen fundoplication has been shown to work with normal and abnormal esophageal motility; (2) that they are better tolerated than a Nissen and should be universally applied, and finally (3) that they are useful in select cases based on an individual’s esophageal motility status (tailored approach). For the sake of this chapter, we will take the position that a tailored approach to antireflux surgery is reasonable, recognizing that there are good arguments for both extremes as well. Because a complex dynamic exists between esophageal motility, lower esophageal sphincter function, gastric function, parasympathetic input, anatomic orientation, and eating behavior, the optimal procedure should be selected for each individual based on a thorough preoperative interview, physical examination, and physiologic evaluation.

Indications: A partial fundoplication should be considered in patients who have a documented need for antireflux surgery and one or more of the following indications.

Patients undergoing an esophagomyotomy (for achalasia, hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter (LES), epiphrenic diverticulum, etc.)

Patients undergoing an esophagomyotomy (for achalasia, hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter (LES), epiphrenic diverticulum, etc.)

Presence of a named primary esophageal motility disorder

Presence of a named primary esophageal motility disorder

Very poor esophageal body motility (peristaltic amplitude <30 mm Hg, >50% simultaneous or dropped peristaltic waves in the esophageal body)

Very poor esophageal body motility (peristaltic amplitude <30 mm Hg, >50% simultaneous or dropped peristaltic waves in the esophageal body)

Severe aerophagia

Severe aerophagia

Inadequate fundus for a full fundoplication

Inadequate fundus for a full fundoplication

Psychological or physical disorders that would not allow the patient to tolerate difficulties with vomiting, belching, or eating large volumes

Psychological or physical disorders that would not allow the patient to tolerate difficulties with vomiting, belching, or eating large volumes

Failure of a full fundoplication due to dysphagia

Failure of a full fundoplication due to dysphagia

Surgeon preference

Surgeon preference

CONTRAINDICATIONS

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Although there are no absolute contraindications to a partial fundoplication compared with a full fundoplication, there are absolute contraindications to antireflux surgery. These include the following.

Inability to tolerate general anesthesia

Inability to tolerate general anesthesia

Severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Uncorrected coagulopathy

Uncorrected coagulopathy

Advanced pregnancy

Advanced pregnancy

Inability to provide informed consent

Inability to provide informed consent

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

The goals of the preoperative evaluation are to confirm the need for an antireflux operation, identify associated pathology that may alter the surgical approach (behavioral, psychological, or associated foregut pathology), and assess overall operative risk. Evaluation always begins with a detailed history and physical examination.

A standardized symptom assessment questionnaire is a useful tool for documenting primary and associated pathology as well as for postoperative follow-up.

A standardized symptom assessment questionnaire is a useful tool for documenting primary and associated pathology as well as for postoperative follow-up.

Every patient being considered for an antireflux operation should have a complete physiologic evaluation that includes 24-hour pH monitoring (± impedance) and esophageal manometry.

Every patient being considered for an antireflux operation should have a complete physiologic evaluation that includes 24-hour pH monitoring (± impedance) and esophageal manometry.

The pH monitoring provides objective evidence of whether reflux exists, rates the severity of reflux, and provides a baseline against which postoperative pH studies can be measured in the event that symptoms fail to resolve or if symptoms recur.

The pH monitoring provides objective evidence of whether reflux exists, rates the severity of reflux, and provides a baseline against which postoperative pH studies can be measured in the event that symptoms fail to resolve or if symptoms recur.

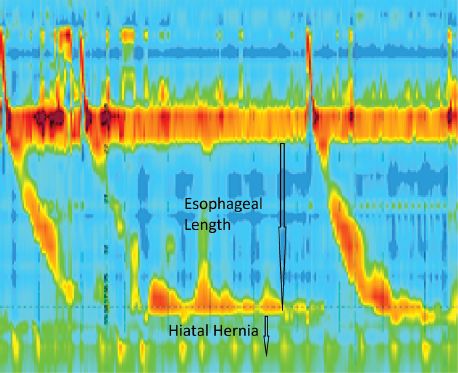

Esophageal manometry is used to identify the type and severity of esophageal motility disorder and evaluate the characteristics of the lower esophageal sphincter. Manometry can also provide important clues regarding esophageal length and the presence of a hiatal hernia (Fig. 2.1). Dysfunctional esophageal motility can be the primary reason for the presenting complaint or it can be a subclinical manometric finding. In either case, manometric findings are often the primary factor guiding the selection of an antireflux technique. Surgeons are strongly encouraged to learn manual interpretation of esophageal manometry tracings, as computer interpretation is unable to differentiate a primary intrinsic motility disorder from a reversible distal esophageal hypocontractility that is secondary to chronic reflux.

Esophageal manometry is used to identify the type and severity of esophageal motility disorder and evaluate the characteristics of the lower esophageal sphincter. Manometry can also provide important clues regarding esophageal length and the presence of a hiatal hernia (Fig. 2.1). Dysfunctional esophageal motility can be the primary reason for the presenting complaint or it can be a subclinical manometric finding. In either case, manometric findings are often the primary factor guiding the selection of an antireflux technique. Surgeons are strongly encouraged to learn manual interpretation of esophageal manometry tracings, as computer interpretation is unable to differentiate a primary intrinsic motility disorder from a reversible distal esophageal hypocontractility that is secondary to chronic reflux.

Figure 2.1 High-resolution manometry is useful to assess esophageal body motility and to screen for hiatal hernia.

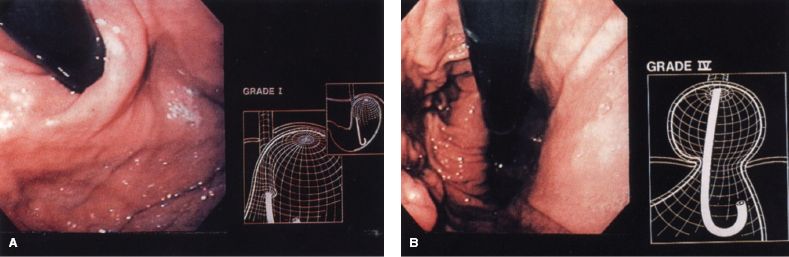

Every patient should have an upper endoscopy to evaluate for cancer, Barrett’s esophagus, a hiatal hernia, diverticula, strictures, esophagitis, and gastric pathology. It is also useful to grade the esophagogastric flap valve as seen in retroflexion based on the Hill standardized scale (Fig. 2.2). Any mucosal lesion should be photographed, biopsied, and described in detail in the endoscopy report. The preoperative endoscopic evaluation is optimally performed by the operating surgeon, because relevant surgical information is often not included in the report when endoscopy is done by someone who is not involved in surgical planning. Upper gastrointestinal contrast studies can provide additional information regarding pharyngeal function, esophageal dilation, esophageal length, hiatal hernia size, and hiatal hernia configuration. Such imaging studies are not mandatory, but should be ordered at the discretion of the operating surgeon if concerns for an alternate or additional pathology are raised during the initial phase of the work-up.

Every patient should have an upper endoscopy to evaluate for cancer, Barrett’s esophagus, a hiatal hernia, diverticula, strictures, esophagitis, and gastric pathology. It is also useful to grade the esophagogastric flap valve as seen in retroflexion based on the Hill standardized scale (Fig. 2.2). Any mucosal lesion should be photographed, biopsied, and described in detail in the endoscopy report. The preoperative endoscopic evaluation is optimally performed by the operating surgeon, because relevant surgical information is often not included in the report when endoscopy is done by someone who is not involved in surgical planning. Upper gastrointestinal contrast studies can provide additional information regarding pharyngeal function, esophageal dilation, esophageal length, hiatal hernia size, and hiatal hernia configuration. Such imaging studies are not mandatory, but should be ordered at the discretion of the operating surgeon if concerns for an alternate or additional pathology are raised during the initial phase of the work-up.

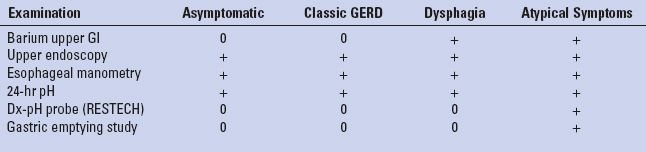

Gastric emptying studies, computed tomography (CT) scans, and direct laryngoscopy are examples of additional tests that are occasionally necessary to arrive at a comprehensive diagnosis (Table 2.1).

Gastric emptying studies, computed tomography (CT) scans, and direct laryngoscopy are examples of additional tests that are occasionally necessary to arrive at a comprehensive diagnosis (Table 2.1).

Figure 2.2 A: Retroflexed endoscopic view of a competent (Hill grade I) valve. B: Retroflexed endoscopic view showing a Hill grade IV valve.

TABLE 2.1 Preoperative Esophageal Tests Vary According to Presentation

SURGERY

SURGERY

General Considerations

Positioning

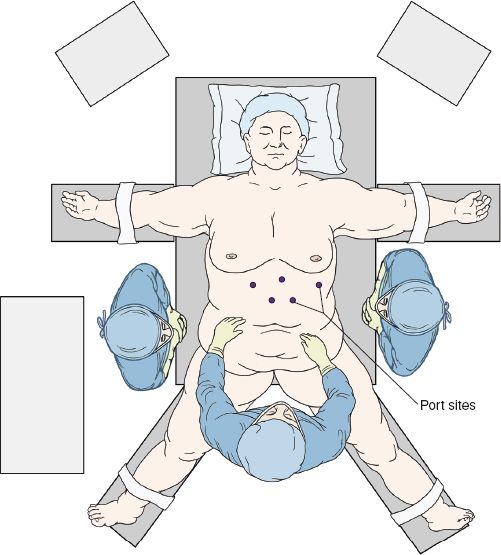

After induction of general anesthesia, the patient is placed in a split-leg position. The patient will be placed in a steep reverse Trendelenburg position during the operation, so it is imperative to secure the patient to the bed and eliminate the possibility of sliding on the table. These goals can be achieved with the aid of tape, a vacuum beanbag mattress, and/or footboards. The arms can be tucked or placed on arm boards and be slightly abducted. The surgeon stands to the patient’s left and the assistant between the legs as seen in Figure 2.3. Also, note the locations of video monitors at the patient’s head and to the right of the head in the direct sight line of both the surgeon and the assistant surgeon. Alternatively, the surgeon can operate from between the legs and the assistant from the patient’s left.

Figure 2.3 Typical OR positioning for a laparoscopic partial fundoplication.

Port Placement

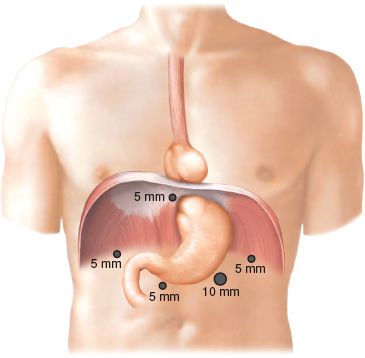

The technique for intra-abdominal access is based on surgeon preference, but is generally similar for all fundoplications. The authors prefer using a Veress needle to insufflate the abdomen. Trocar size is also a matter of preference. The authors’ first port is the camera port, a 10-mm trocar placed 12 cm from the xiphisternum and 3 cm left of the midline. This trocar should be well above the level of the umbilicus. The laparoscope is then inserted and visual exploration of the abdominal cavity is undertaken. Prior to placement of the remaining trocars, the patient is placed in a steep reverse Trendelenburg position. This position allows gravity to gently pull the abdominal viscera out of the hiatus and toward the pelvis. The locations of the remaining trocars are shown in Figure 2.4. Each of these trocars is 5 mm in size and placed under direct visualization. An articulated liver retractor is placed through the right upper quadrant trocar and is used to elevate the left lobe of the liver; the retractor handle is then secured to a table-mounted instrument holder. The surgeon’s left hand instrument works through the trocar that is just below and to the right of the xiphoid process, while the right hand works through the 5 mm trocar in the left upper quadrant. The assistant’s left hand works through the trocar that is 10 cm from the xiphisternum and in the midline.

Dissection

The assistant uses an atraumatic instrument to grasp the epigastric fat pad and retract the stomach downward. Ultrasonic shears are then used to divide the hepatogastric ligament over the caudate lobe. Approximately 15% of patients have a replaced left hepatic artery arising from the left gastric artery and coursing through the hepatogastric ligament. This vessel should be spared if possible, as there are instances, albeit rare, where division results in hepatic ischemia. Dissection is carried toward the hiatus until the right crus is identified.

The assistant uses an atraumatic instrument to grasp the epigastric fat pad and retract the stomach downward. Ultrasonic shears are then used to divide the hepatogastric ligament over the caudate lobe. Approximately 15% of patients have a replaced left hepatic artery arising from the left gastric artery and coursing through the hepatogastric ligament. This vessel should be spared if possible, as there are instances, albeit rare, where division results in hepatic ischemia. Dissection is carried toward the hiatus until the right crus is identified.

Figure 2.4 Typical laparoscopic port placement for fundoplication.

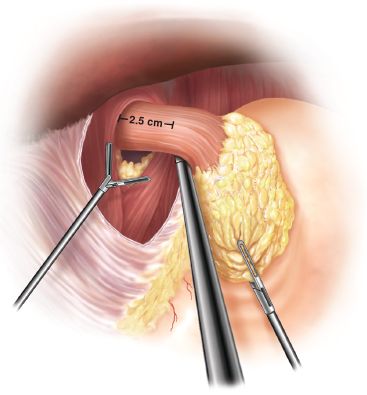

Figure 2.5 Mediastinal dissection usually allows adequate mobilization of the gastroesophageal junction (2.5 to 4 cm).

The phrenoesophageal ligament is incised at the apex of the hiatus allowing entrance into the mediastinum. The mediastinal esophagus is then mobilized using a combination of blunt dissection and ultrasonic dissection. Division of the phrenoesophageal ligament proceeds first along the right crus. Care must be taken to preserve the peritoneal covering of the crura, as this allows a more robust crural closure. Throughout the dissection, the vagi are repeatedly identified and protected by keeping them closely approximated to the esophagus.

The phrenoesophageal ligament is incised at the apex of the hiatus allowing entrance into the mediastinum. The mediastinal esophagus is then mobilized using a combination of blunt dissection and ultrasonic dissection. Division of the phrenoesophageal ligament proceeds first along the right crus. Care must be taken to preserve the peritoneal covering of the crura, as this allows a more robust crural closure. Throughout the dissection, the vagi are repeatedly identified and protected by keeping them closely approximated to the esophagus.

The dissection is then carried into the retroesophageal space. From here, the attachments to the left crus and the fundus can be taken down. The mediastinal dissection is complete when there is 2.5 to 4 cm of tension-free intra-abdominal esophagus (Fig. 2.5). Attention is then turned to the short gastric vessels, which we routinely divide to a variable extent for partial fundoplications to ensure that there is no untoward tension on the wrap. Short gastrics are taken with the ultrasonic shear, starting at the caudal aspect of the upper third of the greater curvature for Toupet, the midpoint of the splenic hilum for Dor, and only the proximal few centimeters for the Hill repair. The stomach is retracted toward the patient’s right, allowing visualization of the retrogastric attachments, which are divided for complete mobilization of the fundus.

The Toupet Fundoplication

The Toupet repair was described as a more physiologic alternative to the Nissen in 1963. Initially a 180-degree posterior wrap with no primary crural closure, it was quickly modified to be a 270-degree wrap with hiatal closure.

Modifications: Crural repair, increased wrap circumference from 180 degrees to 270 degrees

Modifications: Crural repair, increased wrap circumference from 180 degrees to 270 degrees

Operative Technique—The Repair

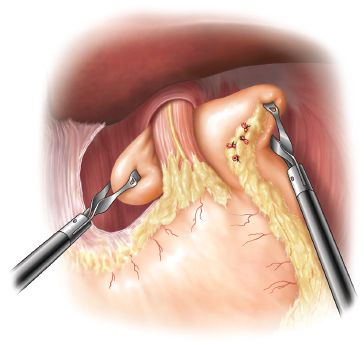

For the Toupet, the gastric fundus must be completely mobilized, both by dividing the short gastric vessels of the upper third of the stomach and by freeing the stomach off the retroperitoneum. With the assistant providing caudal traction on the epiphrenic fat pad, the mobilized fundus is approached from the right, through the retroesophageal window, and brought posterior to the esophagus from left to right. This portion of the fundus is then grasped along the line of divided short gastric vessels with the surgeon’s left hand, while the greater curvature on the left side is held with the right hand and a “shoeshine” maneuver is performed. With the two ends of the wrap retracted away from the esophagus and cephalad toward the diaphragm, the surgeon slides the fundus back and forth behind the esophagus (Fig. 2.6). This maneuver should result in a 1:1 reciprocal movement within each hand. This ensures that the wrap is fully mobilized, is not twisted, and is neither too tight nor too floppy.

Figure 2.6 The “shoeshine” maneuver checks for adequate esophageal length, optimal wrap fixation points, and floppiness of the fundoplication.