INDICATIONS

A short esophagus may be suspected by a preoperative barium esophagram or endoscopic measurement of the distance from the upper esophageal sphincter to the lower esophageal sphincter, but is always confirmed intraoperatively. This shortening of the esophagus is thought to be the result of longitudinal esophageal muscular wall scarring secondary to severe chronic GERD.2,3 The prevalence of short esophagus is controversial but has been estimated to be present in 1.5% to 19% of patients who undergo surgery for GERD.4 – 14 Esophageal shortening can be defined as an intra-abdominal esophageal length less than 2.5 cm even after extensive mediastinal mobilization. If one encounters a shortened esophagus, the first step is to attempt further esophageal mobilization. However, if after all efforts, the intra-abdominal length of esophagus does not appear adequate for a tension-free, intra-abdominal wrap, then consideration for the Collis gastroplasty esophageal-lengthening procedure should be made.15,16

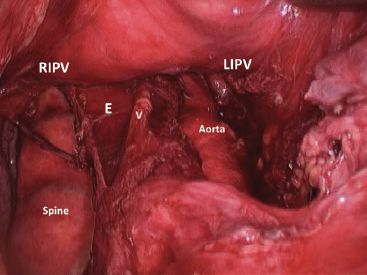

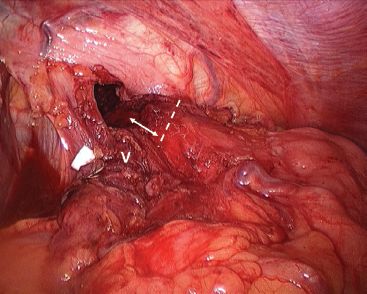

Horvath et al.3 defined three types of esophageal shortening: (1) apparent short esophagus; (2) true, reducible short esophagus; and (3) true, nonreducible short esophagus. Apparent short esophagus is the result of longitudinal compression of the esophagus in the mediastinum, but the esophagus is of normal length. A true, reducible short esophagus is defined as an esophagus that is indeed shortened, but with proper mediastinal mobilization up to and potentially beyond the level of the inferior pulmonary veins (Fig. 6.1), one is able to gain an intra-abdominal length of at least 2.5 cm. A true, nonreducible short esophagus does not allow for an intra-abdominal length of ≥2.5 cm, despite all efforts at esophageal mobilization and mediastinal dissection (Fig. 6.2), and requires a Collis gastroplasty.16 An esophageal intra-abdominal length of ≥2.5 cm is critical to avoid cephalad traction on the completed antireflux wrap and potential wrap herniation.3 As with any other hernia repair, recurrence is more common when the repair is done under tension. The successful surgical management of hiatal herniation may be enhanced when this esophageal-lengthening procedure is included with the standard operative repair in the setting of true, nonreducible esophageal shortening.

Figure 6.1 Laparoscopic view of mediastinal esophageal mobilization. Both inferior pulmonary veins are visible, the esophagus (E) has been dissected free while preserving the vagus nerve (V). RIPV, right inferior pulmonary vein; LIPV, left inferior pulmonary vein.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

CONTRAINDICATIONS

As long as a patient is considered an appropriate candidate for laparoscopic repair of a hiatal hernia, there are no absolute contraindications to performing a laparoscopic Collis gastroplasty. However, there are number of clinical situations where a Collis gastroplasty may be of concern. For example, in the setting of severe esophageal dysmotility with or without stricturing, one would hope to avoid adding a Collis gastroplasty as the dysmotile segment of neoesophagus and a wrap would contribute to postoperative dysphagia. In other cases, where the integrity of the esophagus may be of concern, for example, in difficult hiatal dissections, redo cases, or a difficult giant hernia, significant esophageal trauma may occur with potential myotomies and the safety of adding a Collis staple line may be questionable. Other cases that may be of concern include gastroplasty in compromised, elderly patients with poor tissue integrity or those on steroids where a staple line would preferably be avoided. In any event, we consider the Collis gastroplasty to be a compromise, but one that is necessary if you must do an antireflux procedure and you cannot gain tension-free, intra-abdominal esophagus. These important points emphasize that a Collis gastroplasty should never be used as a substitute to extensive mediastinal mobilization of the esophagus. That is, if you can avoid gastroplasty with good mobilization, then of course do this first. In some patients with a true short esophagus, one may choose to avoid the Collis gastroplasty and the antireflux wrap altogether and perform an esophageal resection with gastric pull-up or a Roux-en-Y esophagojejunal reconstruction as the preferred surgical option. In addition, a surgeon who is not properly trained or sufficiently experienced to technically handle a short esophagus should not perform this operation, and referral to clinical centers handling complex esophageal problems on a regular basis should be considered.

Figure 6.2 Short esophagus. After mediastinal mobilization and GEJ fat pad dissection, it is evident that there is only about 1 cm of esophagus in the abdominal cavity. The dashed line indicates the approximate location of the GEJ, the arrow shows the intra-abdominal length of esophagus. V, vagus nerve and mobilized fat pad.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

The surgeon must consider the possible need for esophageal-lengthening procedure in patients with a large hiatal hernia (>5 cm), a peptic stricture, long-segment Barrett’s esophagus (>3 cm), or a previous failed repair of a hiatal hernia. Because obesity increases intra-abdominal stress on any hernia repair, an esophageal-lengthening procedure should also be considered in obese patients undergoing hiatal hernia surgery.5,13,14

The clinical work-up of a patient being considered for hiatal hernia repair and antireflux surgery should include the following.

A barium esophagram to assess the size of the hernia and the presence of axial or longitudinal rotation and strictures.

A barium esophagram to assess the size of the hernia and the presence of axial or longitudinal rotation and strictures.

An upper endoscopy to measure the distance from the GEJ to the crural impression (i.e., hernia size) and to thoroughly examine the mucosa. Any mucosal abnormalities should be biopsied.

An upper endoscopy to measure the distance from the GEJ to the crural impression (i.e., hernia size) and to thoroughly examine the mucosa. Any mucosal abnormalities should be biopsied.

Esophageal manometry to assess motility. In the setting of severe motor dysfunction, we prefer to avoid a Collis if at all possible. This may lead to a decision to perform a partial wrap or in severe cases an esophagectomy or Roux-en-Y.

Esophageal manometry to assess motility. In the setting of severe motor dysfunction, we prefer to avoid a Collis if at all possible. This may lead to a decision to perform a partial wrap or in severe cases an esophagectomy or Roux-en-Y.

24 hour (or longer) pH study.

24 hour (or longer) pH study.

Gastric emptying studies if clinically indicated, for example, redo cases or patients with diabetes.

Gastric emptying studies if clinically indicated, for example, redo cases or patients with diabetes.

A computerized tomography scan can occasionally be helpful but is not routinely required prior to hiatal hernia surgery.

A computerized tomography scan can occasionally be helpful but is not routinely required prior to hiatal hernia surgery.

With the clinical information provided by the barium esophagram and endoscopy, the esophageal surgeon should be able to identify those patients at greatest risk for esophageal shortening and, accordingly, be prepared to perform esophageal-lengthening Collis gastroplasty if true esophageal shortening is present.

SURGERY

SURGERY

Positioning

The patient should be in a supine position, on a table capable of steep reverse Trendelenburg, with arms abducted.

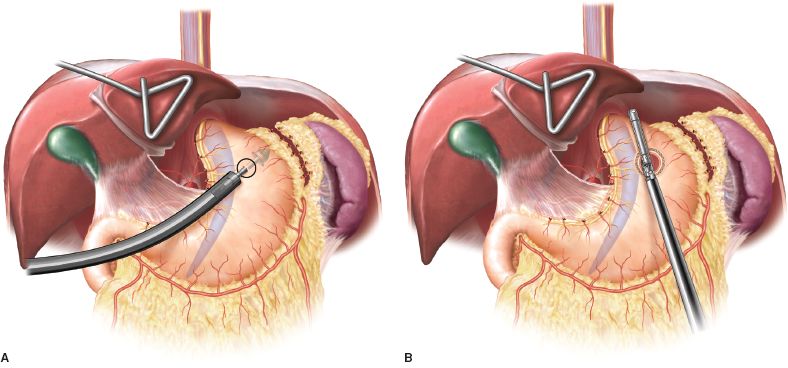

Figure 6.3 Collis gastroplasty using an EEA (A) and linear stapler (B) as originally described by Steichen and Champion.

Technique

Our initial surgical technique for laparoscopic gastroplasty, as part of a hiatal hernia repair, was based on the original procedure used by Felix Steichen for open gastroplasties.17 This was later described laparoscopically by Champion and others for laparoscopic vertical banded gastroplasty.4 In that procedure, a large esophageal bougie is placed into the upper stomach alongside the lesser curvature, and an EEA stapler is used to create a “doughnut hole” in the upper stomach alongside the margin of the lesser curvature. After successful creation of the “doughnut hole,” a linear endostapler is positioned within the hole, next to the lesser curvature gastric margin and against the intraesophageal bougie. The stapler is fired in a cephalad direction to create the neoesophagus from the lesser curvature stomach tube (Fig. 6.3).18

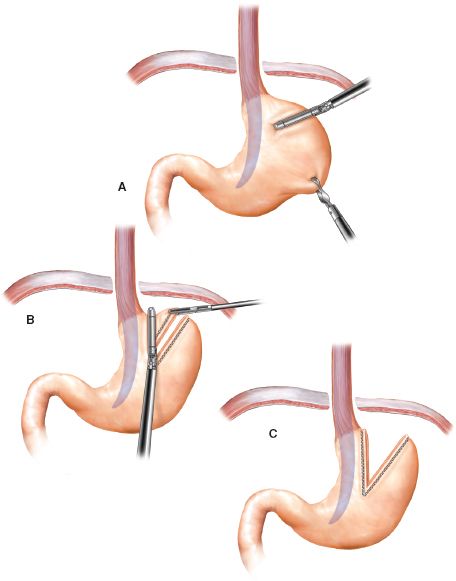

More recently, we have adopted the “wedge” gastroplasty approach (Fig. 6.4) which was used by Champion and described by Hunter and colleagues.19 This approach is easier to master and in most hands reduces the likelihood of staple-line leakage.

Operative steps for hiatal hernia repair and Collis gastroplasty using the wedge approach include the following.

Hernia sac reduction and excision.

Hernia sac reduction and excision.

Extensive mediastinal esophageal dissection with vagal nerve preservation (Fig. 6.1).

Extensive mediastinal esophageal dissection with vagal nerve preservation (Fig. 6.1).

GEJ fat pad dissection and evaluation of intra-abdominal esophageal length (Fig. 6.2). Intraoperative endoscopy can be of help to define the exact location of the GEJ. The anterior vagus nerve is dissected off the GEJ and proximal stomach. The intra-abdominal esophageal length is best determined after partial closure of the hiatus.

GEJ fat pad dissection and evaluation of intra-abdominal esophageal length (Fig. 6.2). Intraoperative endoscopy can be of help to define the exact location of the GEJ. The anterior vagus nerve is dissected off the GEJ and proximal stomach. The intra-abdominal esophageal length is best determined after partial closure of the hiatus.

Placement of a 48-French esophageal dilator along the lesser curvature.

Placement of a 48-French esophageal dilator along the lesser curvature.

The tip of the fundus is retracted inferiorly to expose the greater curvature for stapler application (Fig. 6.5).

The tip of the fundus is retracted inferiorly to expose the greater curvature for stapler application (Fig. 6.5).

The endoscopic GIA stapler is introduced through a left upper quadrant port (Fig. 6.6). The first staple line determines the appropriate level of transection of the greater curvature (Fig. 6.4, panel A and Fig. 6.7). A second and sometimes third staple line is applied to end snuggly at the edge of the dilator (Fig. 6.8).

The endoscopic GIA stapler is introduced through a left upper quadrant port (Fig. 6.6). The first staple line determines the appropriate level of transection of the greater curvature (Fig. 6.4, panel A and Fig. 6.7). A second and sometimes third staple line is applied to end snuggly at the edge of the dilator (Fig. 6.8).

The wedge is excised with a final staple line from a right upper quadrant port (Fig. 6.4, panel B and Fig. 6.9). This is easier to do with the hiatus partially closed, because it allows the tip of the stapler to enter the mediastinum.

The wedge is excised with a final staple line from a right upper quadrant port (Fig. 6.4, panel B and Fig. 6.9). This is easier to do with the hiatus partially closed, because it allows the tip of the stapler to enter the mediastinum.

The Collis segment (neoesophagus) is approximately 2.5 cm in length (Fig. 6.4, panel C and Fig. 6.10).

The Collis segment (neoesophagus) is approximately 2.5 cm in length (Fig. 6.4, panel C and Fig. 6.10).

Figure 6.4 Collis wedge gastroplasty.