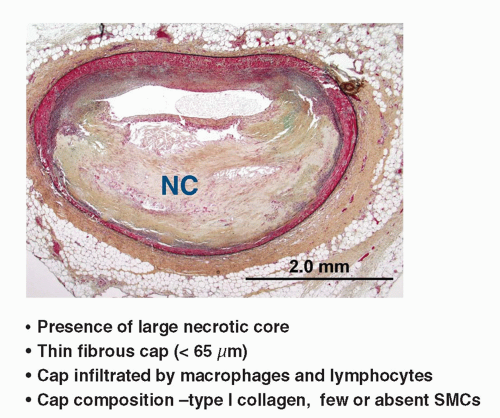

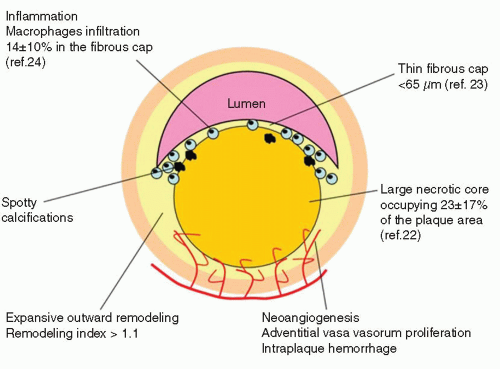

FIGURE 9-2 Typical morphologic traits associated with rupture prone plaques. (From: Vancraeynest D, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1961-1979, with permission.) |

Architecture: Plaque volume, length, remodeling, eccentricity, impact on lumen area, fibrous cap thickness, evidence of disruption;

Physiology: Impact on coronary flow reserve;

TABLE 9-1 Histologic Features of Suspected Vulnerable Plaquesa

Type

Features

nflamed thin-cap fibroatheroma, most frequent type and present in 60% to 70% of ACS cases

Necrotic core (lipid core) Thin cap <65µm nflammation

Erosion site, present in 20% to 30% of events, more frequent in women and younger patients with ACS

Increased vasa vasorum

Expansive remodelling

Increased plaque burden

Intraplaque hemorrhage

Calcified nodule, present in <3% of patients with ACS

Spotty calcification

Luminal narrowing

Plaque with a mural thrombus not producing a significant stenosis

Increased proteoglycans

Extensive calcification protruding into lumen

Considered to be a site of subsequent thrombosis because many plaque-causing events show repeated episodes of disruption and thrombosis

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; Ml, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TCFA, thin cap fibroatheroma

aaFrom: Muller JE et al. J Am Coll Cardiol Imaging. 2010;3:881-891

Composition: Lipid-necrotic core, fibrous, hemorrhage, calcium, etc.;

Pathobiology: Presence of inflammation, neovascularization, fibrous cap metabolism, apoptosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree