Interventional Bronchoscopy

INTRODUCTION

The first interventional bronchoscopy (also referred to as therapeutic bronchoscopy throughout this chapter) was performed by Gustav Killian in 1897 when he removed a pork bone from the right mainstem bronchus of a patient. For nearly 70 years bronchoscopy was predominantly a therapeutic procedure performed for foreign body extraction. Two events shifted the landscape of bronchoscopy—the lung cancer epidemic and the development of flexible bronchoscopy by Shigeto Ikeda in 1967. Following an escalation in lung cancer incidence, malignant airway obstruction requiring therapeutic intervention became much more common than foreign body extraction. As a result, new tools were developed to address malignant airway obstruction based upon a minimally invasive bronchoscopic approach. In addition, bronchoscopy-based technology has been developed to address chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma. Application of the technology has entered clinical trials and may alter the therapeutic options for these diseases processes. This chapter presents an overview of interventional bronchoscopy modalities that can be utilized for benign and malignant airway obstruction, COPD, and asthma.

INDICATIONS FOR interventional BRONCHOSCOPY

Many potential indications for interventional bronchoscopy have been recognized, including malignant airway obstruction, benign airway obstruction, and foreign body extraction, among others. (Table 36-1). The majority of therapeutic bronchoscopies performed today are undertaken for management of malignant airway obstruction, most commonly from lung cancer. It is estimated that up to 40% of patients with lung cancer develop symptomatic airway obstruction at some point during their disease process. Although lung cancer is the most common source of malignant airway obstruction, any primary thoracic malignancy, or any malignancy with pulmonary metastases, may result in symptomatic airway obstruction. Regaining airway patency to palliate symptomatic dyspnea and other respiratory symptoms may have significant impact on the quality of life of patients with advanced malignancy.

Benign airway obstruction etiologies are listed in Table 36-2 and consist of a variety of localized inflammatory and systemic conditions. Although the etiologic airway process is benign and not malignant, the interventions and management of these complex processes is far from benign to the patient. Interventional bronchoscopy techniques can often correct the presenting symptoms; however, the stenosis and symptoms often recur and patients may require repeat procedures to maintain airway patency. Selected patients may need to proceed with airway resection of the benign stenotic airway segment.1

Most patients with airway obstruction have clinical symptoms; dyspnea as the most common patient complaint. Depending on the rapidity of airway obstruction, dyspnea may have a rapid onset, or more commonly, an insidious evolution that gradually limits the patient activities. It is not uncommon for a family member to recognize this limitation more readily than the patient. As the airway obstruction worsens, the patient may begin to have orthopnea, which is a harbinger of an evolving critical airway obstruction. Other symptoms, such as cough, inability to clear secretions, chest discomfort, or fever from post obstructive pneumonia may develop. Early intervention is important to prevent worsening respiratory compromise or death.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR PATIENT PREPARATION, SEDATION, AND MONITORING

All patients undergoing bronchoscopy should undergo a complete pre-bronchoscopy evaluation, including a medical history, physical examination, and chest imaging. Although routine laboratory tests are not required, each evaluation should be individualized on the basis of patients’ underlying conditions and therapeutic procedures planned. CT scan is important to assess the degree of airway involvement and to plan interventions to be undertaken.

Sedation and analgesia for patients undergoing interventional bronchoscopy must be considered carefully. Stable patients who can lay flat without distress can undergo bronchoscopy with moderate sedation. Should the patient have moderate or severe respiratory distress or be unable to lay flat, strong consideration should be given to additional monitoring or anesthesiology procedural assistance. Patients with high oxygen requirements may require endotracheal intubation to reduce the risk of developing hypoxemic respiratory failure during moderate sedation. Moreover, if patients are unable to lie flat, they may require an initial upright bronchoscopy under minimal sedation to temporize luminal diameter before undergoing general anesthesia and more definitive interventional bronchoscopy.

Similar to diagnostic bronchoscopy, if a patient is stable for moderate sedation, topical analgesia of the oropharynx and airways should be achieved with lidocaine, followed by administration of a combination of a short-acting benzodiazepine (e.g., midazolam) and a narcotic (e.g., fentanyl).2 Rigid bronchoscopy is most safely performed with a patient receiving general anesthesia and breathing spontaneously or being ventilated with a jet ventilator.3 General anesthesia with inhaled anesthetics (e.g., sevoflurane) should be avoided in favor of total intravenous anesthesia in order to avoid exposure of the bronchoscopist to inhaled anesthetics when the ventilator circuit is open. With appropriate planning and monitoring, the vast majority of patients can undergo interventional bronchoscopy with low complication rates.

TYPES OF AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

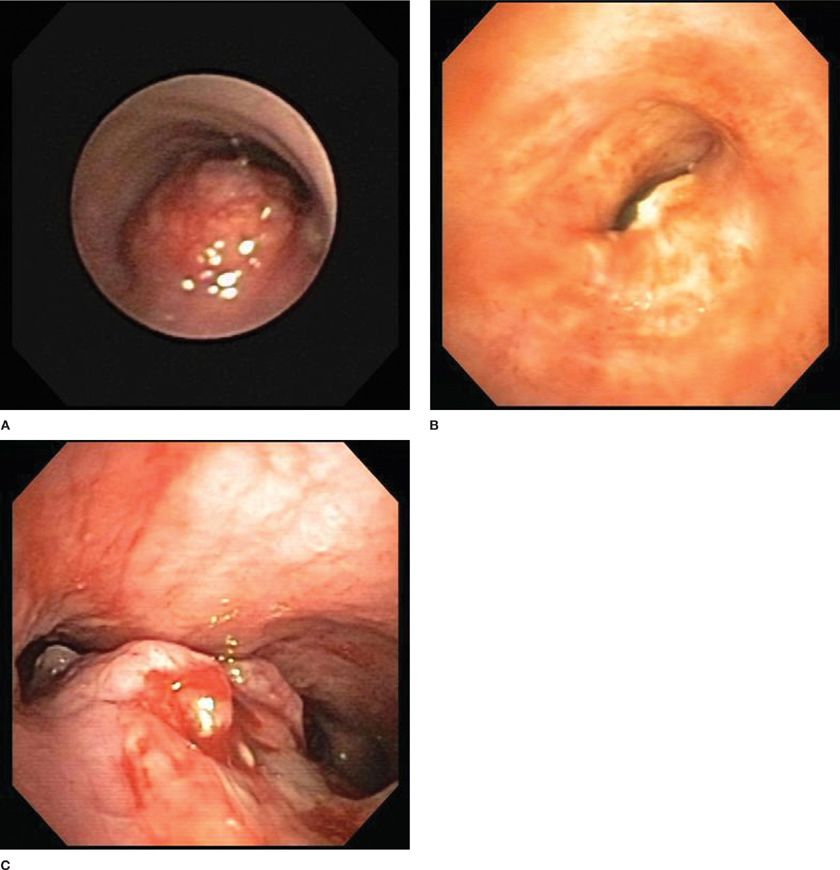

Figure 36-1 demonstrates the three main types of airway obstruction that may be encountered: purely intrinsic (A), purely extrinsic (B), or a combination of both intrinsic and extrinsic airway obstruction (C). Attention to preprocedural CT scan imaging allows fairly accurate assessment of these components and permits the therapeutic bronchoscopist to plan an approach. For lesions that are purely intrinsic, direct bronchoscopic debulking with rigid bronchoscopy, thermal ablation, or snare extraction, with or without stent placement, is appropriate. For purely extrinsic lesions, no tumor is present to debulk, and modalities used in purely intrinsic disease cannot be employed because of the risk of airway perforation. Extrinsic lesions are most amenable to balloon bronchoplastic dilatation and endoluminal stent placement. For mixed intrinsic–extrinsic lesions, all tumor removal modalities, as well as dilatation and stent placement, are feasible.

Figure 36-1 Types of airway compression. Intrinsic (A). Extrinsic (B). Mixed intrinsic and extrinsic (C).

ENDOLUMINAL AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

ENDOLUMINAL AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

Endoluminal obstruction of the tracheobronchial tree may result from various benign and malignant processes. The most common cause of endobronchial obstruction is advanced lung carcinoma. In patients with inoperable central airway tumors, restoration of airway patency may provide palliation and may even prolong life, particularly in the case of impending respiratory failure or postobstructive pneumonia.

Signs and symptoms of central malignant airway obstruction vary, but often include progressive dyspnea and functional limitation, wheezing, cough, stridor, hoarseness, hemoptysis, and chest pain. A careful pretreatment evaluation should be performed to distinguish symptoms attributable to focal tracheobronchial lesions from those related to underlying obstructive lung disease, parenchymal lung disease, or both. Although pulmonary function testing and thoracic imaging techniques, such as chest CT, may be useful in the evaluation of a patient with suspected malignant airway obstruction, bronchoscopy, either rigid or flexible, remains the diagnostic and therapeutic “gold standard.” Increasingly, however, three-dimensional reconstruction CT imaging, so-called “virtual bronchoscopy,” is being applied as a reliable noninvasive method of assessing the nature and extent of malignant airway obstruction, thereby allowing preprocedural intervention planning.

The bronchoscopic approach to management of malignant airway obstruction depends on the lesion location, presence or absence of associated extrinsic compression, and degree of clinical urgency. Rigid bronchoscopic debulking using adjunctive thermal ablation is recommended when airway recanalization must be performed on an emergency basis. If endobronchial obstruction is accompanied by marked extrinsic compression, stent placement may be beneficial.

The complexity of a lesion is equally important in determining the best approach to therapeutic bronchoscopy. Benign tracheal webs often are managed using laser or electrocautery-mediated resection alone, whereas complex fibrotic strictures may warrant the combination of rigid bronchoscopic or balloon dilation, thermal incision, and stent placement. For focal tracheal stenosis in patients at low risk for complications, surgical resection with primary re-anastomosis should remain the treatment of choice.

EXTRINSIC AIRWAY COMPRESSION

EXTRINSIC AIRWAY COMPRESSION

Extrinsic airway compression usually results from malignant involvement of structures adjacent to the central airways, such as mediastinal lymph nodes or the esophagus, but it may be associated with a benign process, such as fibrosing mediastinitis, tuberculosis, aneurysmal dilatation of the aorta, or sarcoidosis. The clinical signs and symptoms of extrinsic airway compression often mimic those of endobronchial obstruction. The diagnosis is established on the basis of bronchoscopic detection of marked airway narrowing in the absence of an endoluminal mass.

Therapeutic options in the management of extrinsic airway compression are limited. Ablative endoscopic approaches, such as laser therapy, cryotherapy, PDT, and electrocautery are contraindicated because of the lack of demonstrable benefit and risk of airway perforation. Although some patients with malignant disease may benefit from endobronchial brachytherapy, tracheobronchial stent placement is the palliative treatment of choice for patients with symptomatic extrinsic airway compression.

TYPES OF THERAPEUTIC BRONCHOSCOPY INTERVENTIONS

A wide variety of therapeutic bronchoscopic interventions may be offered. Each is described in subsequent sections.

RIGID BRONCHOSCOPY

RIGID BRONCHOSCOPY

The initial bronchoscope, developed by Killian, and further optimized by Chevalier Jackson, was a rigid metal tube that permitted either spontaneous or mechanical ventilation.4 Over the decades, rigid bronchoscopes of various lengths and sizes that are adaptable for diverse applications in children and adults have become available. Although the flexible bronchoscope has, to a large extent, replaced the rigid scope for most diagnostic and some therapeutic indications, rigid bronchoscopy still has vital therapeutic applications.

Modern rigid bronchoscopy systems are equipped with optical capabilities to allow better direct, magnified, circumferential illumination and visualization. The main advantage of rigid bronchoscopy over flexible bronchoscopy is its luminal working diameter, which allows multiple therapeutic instruments to be utilized simultaneously while ventilating the patient. Rigid bronchoscopy allows a number of therapies, such as laser photocoagulation, placement of endobronchial stents, balloon dilation, electrocautery, argon beam coagulation, and cryotherapy to be performed safely and effectively. Perhaps most importantly, in the setting of malignant airway disease or obstruction, a rigid bronchoscope can be used to “core out” large bulky airway tumors more efficiently and effectively than any thermal modalities (Video 36-1). Initial rigid bronchoscopic debulking, followed by thermal modality ablation to cauterize remaining tumor is common.5 For benign, fibrotic airway stenosis, the rigid bronchoscope becomes a very effective modality to partially debulk stenotic tissue and to dilate the stenosis.6 In experienced centers, rigid bronchoscopic airway recanalization remains the treatment of choice for serious or life-threatening tracheobronchial obstruction.

Video 36-1 A patient with a right paratracheal mass who underwent diagnostic and therapeutic bronchoscopy. Endoluminal tumor growth was present along the right lateral tracheal wall. The video demonstrates effective and efficient use of rigid bronchoscopy to mechanically debride tumor. Access at www.fishmansonline.com

The main complication from rigid bronchoscopy is dental injury from the scope cracking or fracturing teeth. Other complications, such as oropharyngeal laceration, arytenoid cartilage disarticulation, or vocal cord injury, are possible. Meticulous care upon rigid bronchoscope intubation is critical to avoid these possible complications. Intrathoracic complications, such as airway perforation, major bleeding from tumor debulking, and pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum are also possible but are infrequent in experienced hands.

BALLOON TRACHEOBRONCHOPLASTY

BALLOON TRACHEOBRONCHOPLASTY

Balloon dilatation has become an attractive alternative to rigid bronchoscopy for management of airway obstruction in benign and malignant airway obstruction, especially in anatomic locations where a rigid bronchoscope cannot enter or the luminal diameter is too narrow to allow safe rigid bronchoscope passage. High-pressure balloons of various lengths and diameters specifically designed for the tracheobronchial tree are readily available. These balloons are filled with saline or radio-opaque contrast media, advanced to the site of interest through the bronchoscope, and inflated until the desired diameter is attained.

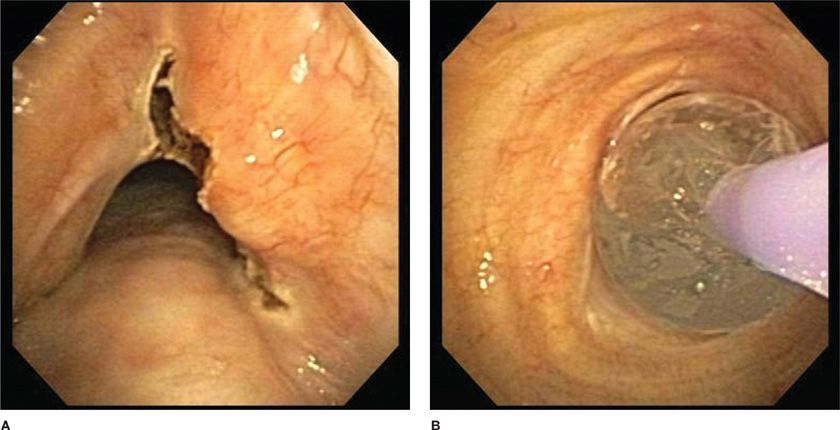

In the setting of benign stenosis, an initial defect in the stenosis is often made with a thermal modality so as to control the stenotic release point (Fig. 36-2). This approach has been used successfully in benign stenoses from endobronchial tuberculosis, idiopathic subglottic stenosis, and post-transplant anastomotic strictures.7 It is less successful when used alone to treat airway compromise accompanied by extrinsic airway compression, as the initial bronchoscopic improvement often rapidly returns to its original position as the extrinsic process persists. Complications of balloon tracheobronchoplasty include bronchospasm, chest pain, mucosal laceration, airway perforation, bleeding, postprocedure airway edema, pneumothorax, and pneumomediastinum.

Figure 36-2 Electrocautery incisions were made into the benign stenotic lesion (A). Following incision, balloon bronchoplasty dilatation was performed (B).

BRONCHOSCOPIC LASER THERAPY

BRONCHOSCOPIC LASER THERAPY

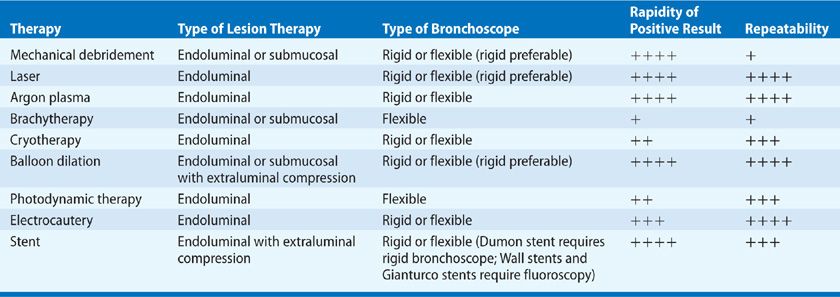

Perhaps the most widely known technique in therapeutic bronchoscopy is laser photocoagulation or photoablation. Table 36-3 compares characteristics of the laser modality compared with other modalities to be presented later. Lasers produce a beam of monochromatic, coherent light that induces tissue vaporization, coagulation, hemostasis, and necrosis. Although primarily useful in endoluminal malignant tumor ablation, bronchoscopic laser therapy also is beneficial in other tracheobronchial disorders, including inflammatory strictures, obstructive granulation tissue, amyloidosis, and benign tumors, such as hamartomas and lipomas.

Since the initial report of endobronchial laser ablation of an obstructive neoplasm by Laforet in 1976, several types of lasers have become available for management of tracheobronchial obstruction.8 The carbon dioxide (CO2) laser, used primarily by otolaryngologists, allows shallow tissue penetration (to a depth of 0.1–0.5 mm) and very precise cutting, but it has minimal hemostatic properties. With the development of other laser modalities, the CO2 laser has minimal current application in endobronchial tumor ablation, and its role remains primarily in management of laryngeal lesions.

For therapeutic bronchoscopy, neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG) laser ablation is most commonly used (Video 36-2). It provides tissue penetration to a depth of 3 to 5 mm, superior coagulation and improved hemostasis, but at the cost of less cutting precision. Nd:YAG laser procedures may be performed through a rigid or flexible bronchoscope. Success rates and complications directly related to laser therapy are not different when the procedure is performed through a rigid bronchoscope with the patient under general anesthesia, or through a flexible bronchoscope with use of topical anesthesia and moderate sedation.

Video 36-2 A patient who presented with a new right mainstem obstruction from lung cancer. The video shows Nd:YAG tumor coagulation and debulking. Access at www.fishmansonline.com

Use of Nd:YAG laser photoablation therapy as a single modality is associated with a recanalization rate >90% for endobronchial obstruction of large central airways; however, it is less successful in treating peripheral lesions or extrinsic airway compression.9,10 Nd:YAG laser photocoagulation may be an important treatment tool for patients with airway obstruction caused by benign endoluminal tumors. The Nd:Yap (yttrium-aluminum-perovskite) laser, with a patented wavelength of 1.34 μ wavelength, is purported to have better water absorption at that wavelength, improving the power-to-effective ratio compared with traditional Nd:YAG laser and carrying a lower complication risk.

Although endobronchial laser therapy generally is safe and well tolerated, it may be complicated by cardiac arrhythmias, airway perforation, pneumothorax, hemorrhage, hypoxemia, or endobronchial fire.11,12 Endoluminal laser utilization requires careful consideration of the lesion anatomic location and configuration relative to vital intrathoracic structures. If the lesion is in close proximity to the esophagus or pulmonary artery, endobronchial laser therapy carries risk for fistula formation. Laser therapy in a patient with tracheobronchial narrowing caused by extrinsic compression may result in airway perforation. In rare cases, pulmonary edema or fatal pulmonary venous gas embolism have been reported.13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree