3

CHAPTER

![]()

Interstitial Diseases II: Fibrotic Variants

As in Chapter 2, this chapter includes only those conditions that predominantly involve the interstitium with relative sparing of airspaces. In contrast, however, this chapter includes conditions in which fibrosis predominates over inflammation. As noted in the previous chapter, a few conditions are included in both chapters, as the relative proportions of inflammation and fibrosis may vary, and, in these cases, both chapters may need to be searched to find the appropriate diagnosis. Certain pneumoconioses that may also have a fibrosing interstitial pattern are discussed in Chapter 9.

TOPICS

Usual Interstitial Pneumonia (UIP)

Usual Interstitial Pneumonia (UIP)

Fibrotic Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonia (NSIP)

Fibrotic Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonia (NSIP)

Scarred Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH)

Scarred Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH)

Smoking-Related Interstitial Fibrosis (SRIF)

Smoking-Related Interstitial Fibrosis (SRIF)

Collagen Vascular Disease–Associated Interstitial Fibrosis

Collagen Vascular Disease–Associated Interstitial Fibrosis

Nonclassifiable Interstitial Fibrosis

Nonclassifiable Interstitial Fibrosis

Rare, Unproven Entities

Rare, Unproven Entities

Pleuroparenchymal Fibroelastosis (PPFE)

Pleuroparenchymal Fibroelastosis (PPFE)

Bronchiolocentric Interstitial Pneumonia

Bronchiolocentric Interstitial Pneumonia

USUAL INTERSTITIAL PNEUMONIA (UIP)

Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) is the most common idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Although diagnostic radiologic features have been recognized in recent years that obviate the need for biopsy in about one half of patients, many patients still require biopsy for diagnosis. The pathologic diagnosis may be especially challenging in those cases, and strict diagnostic criteria need to be followed.

Histologic Features

Nonuniform, patchwork pattern of interstitial fibrosis

Nonuniform, patchwork pattern of interstitial fibrosis

Architectural distortion (honeycomb change and/or scars)

Architectural distortion (honeycomb change and/or scars)

Temporal variegation (fibroblast foci and collagen)

Temporal variegation (fibroblast foci and collagen)

Minimal interstitial inflammation

Minimal interstitial inflammation

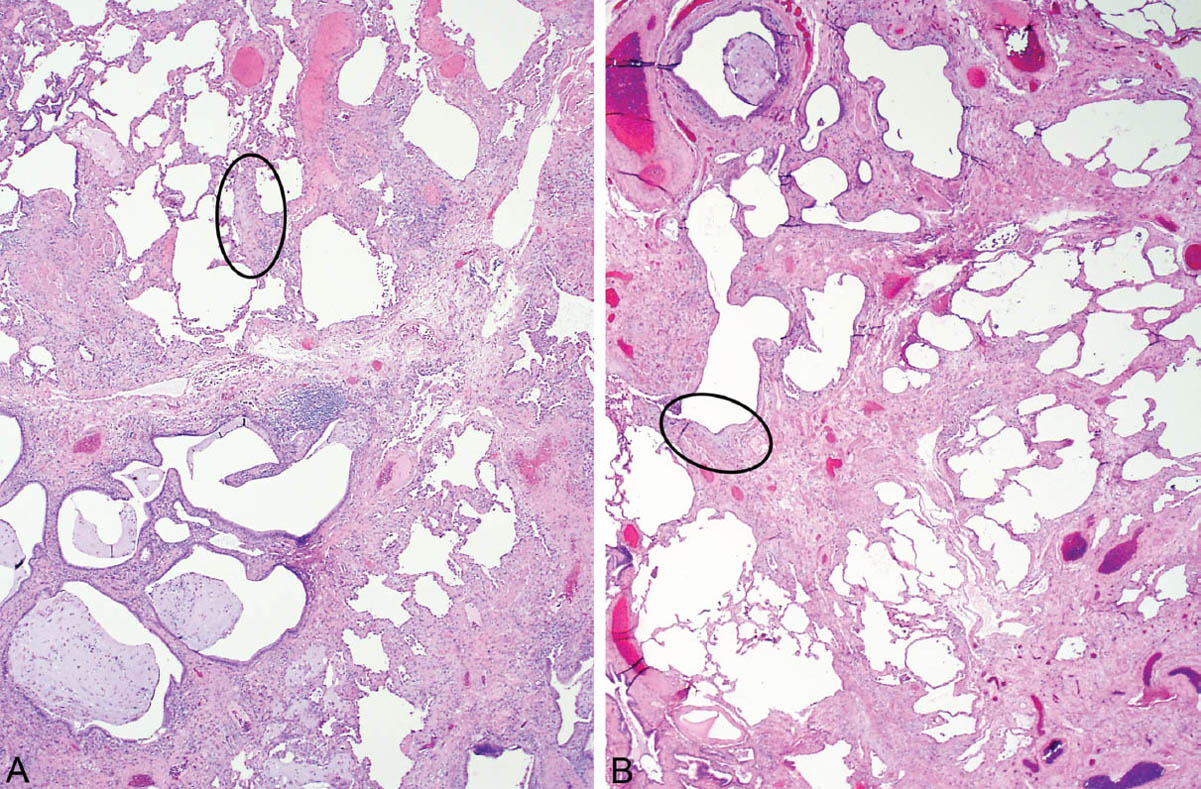

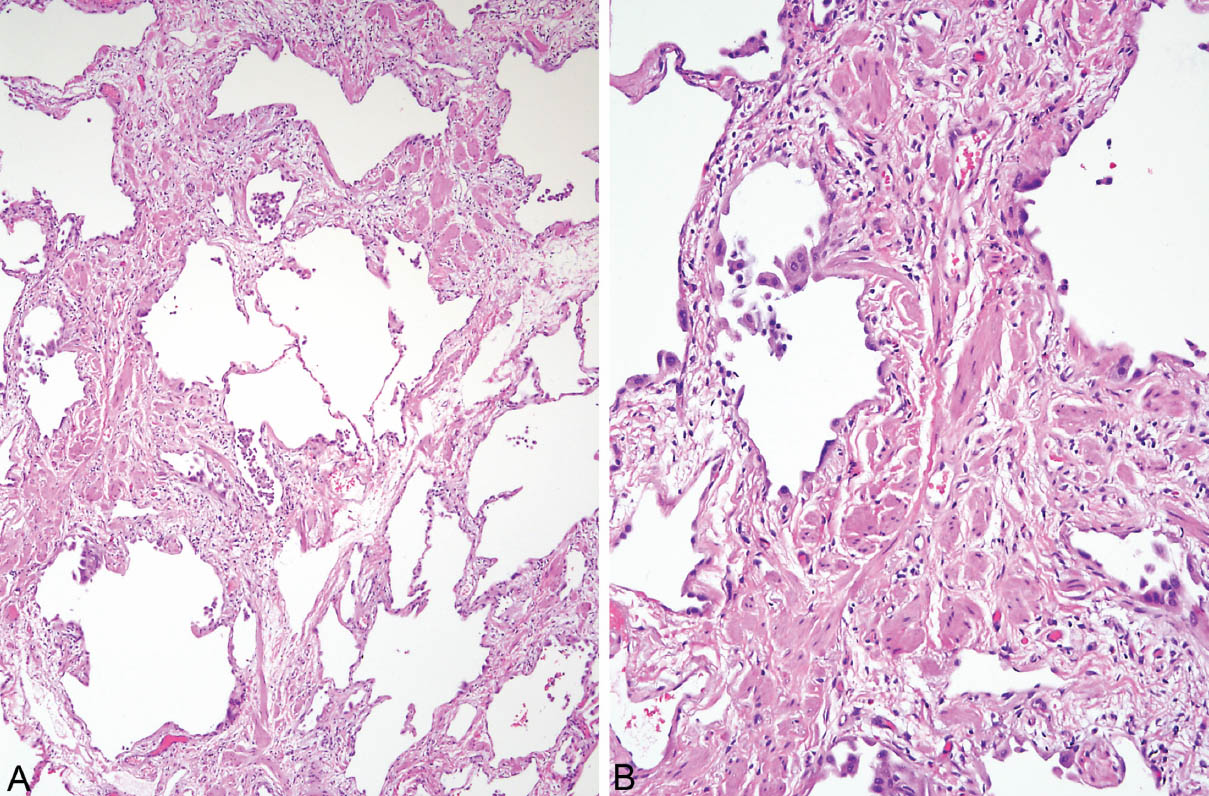

UIP has a characteristic nonuniform, heterogeneous appearance at low magnification, which is caused by alternating zones of abnormal, fibrotic parenchyma and islands of relatively normal lung (Figure 3.1). This seemingly random juxtaposition of abnormal and normal zones without intervening transition has been described as a patchwork pattern because of its resemblance to the apposition of different patterns in a patchwork quilt.

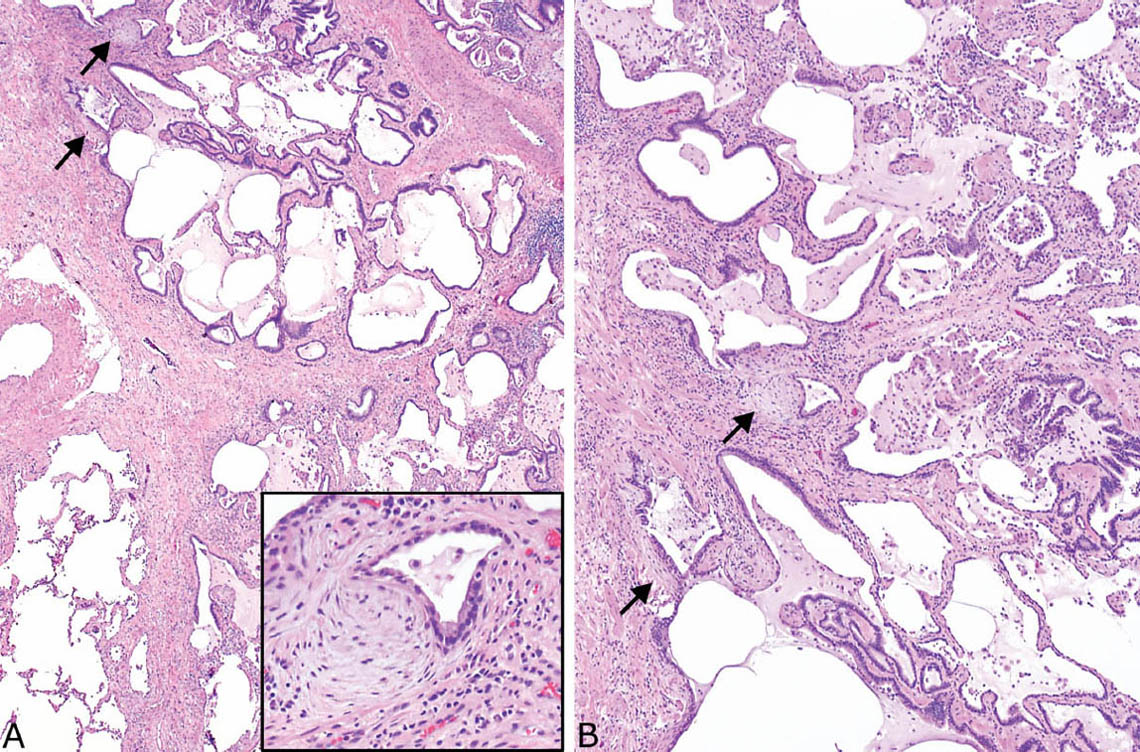

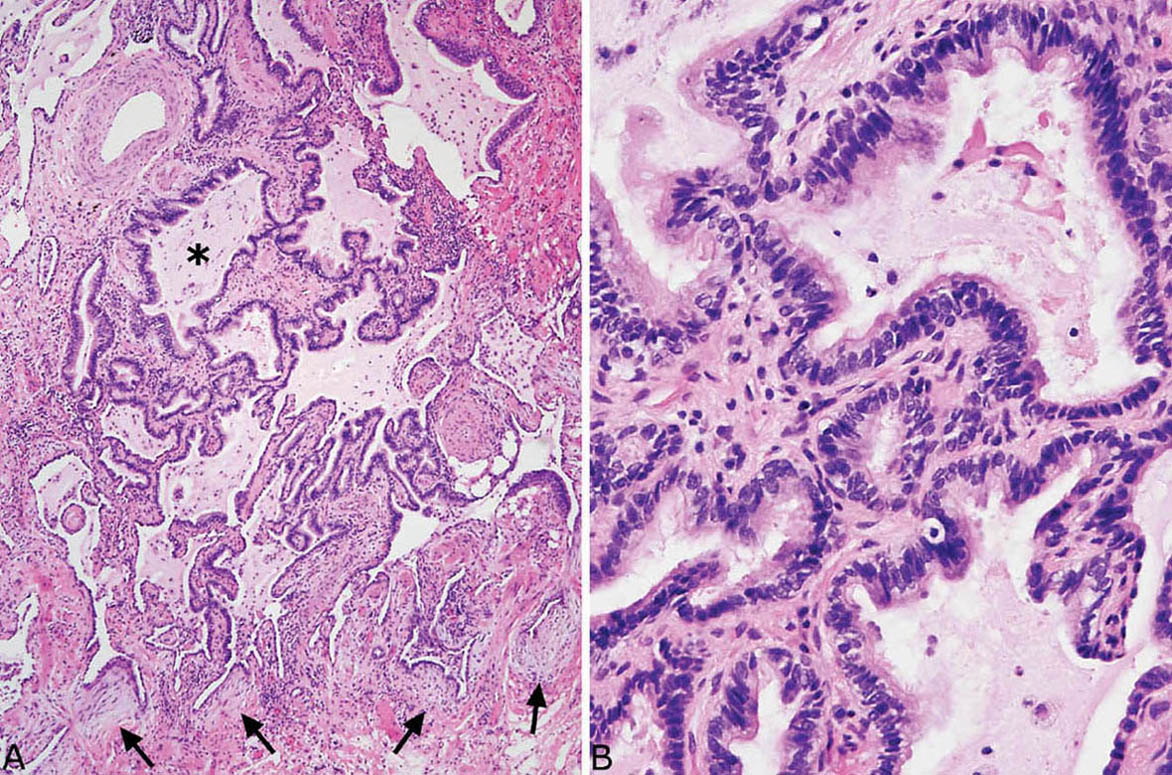

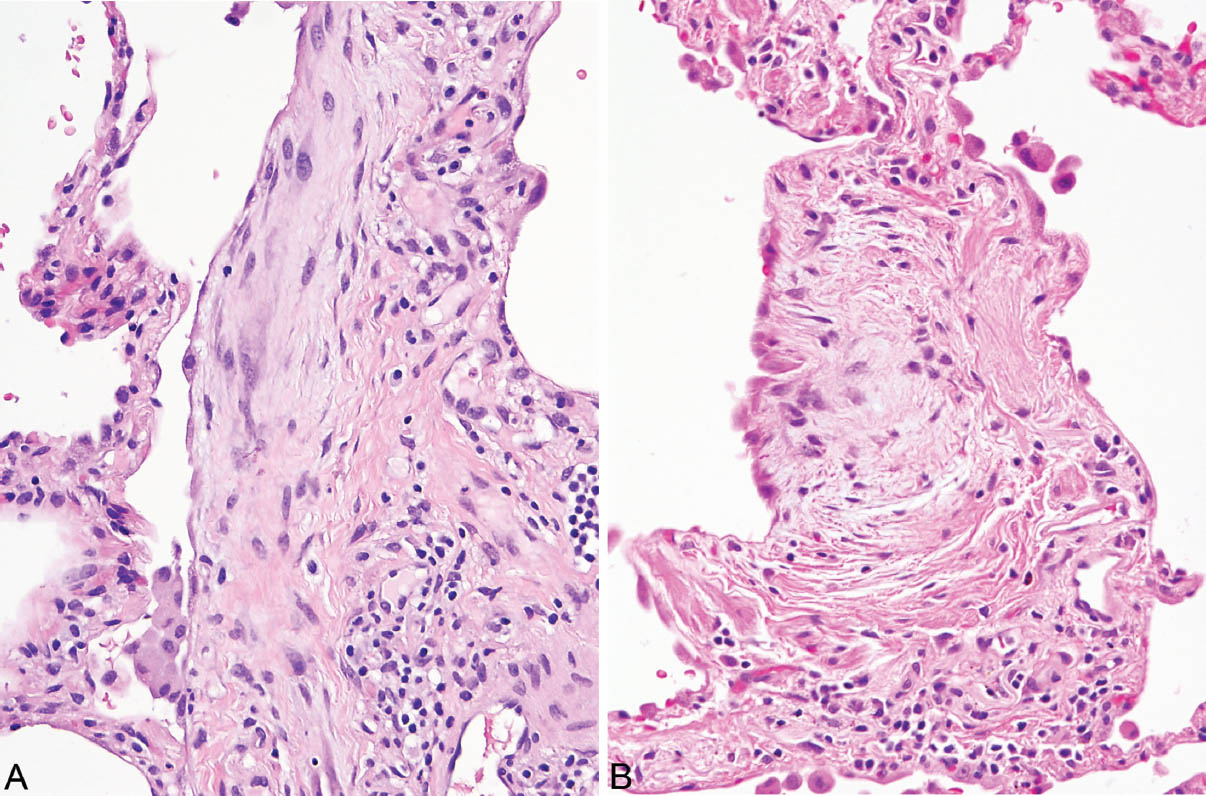

Architectural distortion is defined as destruction of normal alveolar structure and replacement by fibrous scars, honeycomb change, or both, and it is requisite for diagnosis. Honeycomb areas are almost always present and are usually accompanied by scars, but in rare cases honeycomb change is absent and scars are the only manifestation of architectural distortion. Honeycomb change is a form of end-stage, irreversibly damaged lung and is typified by the replacement of parenchyma by enlarged, restructured airspaces usually lined at least partially by bronchiolar epithelium and surrounded by dense collagen-type fibrosis (Figures 3.2 and 3.3). Residual intact bronchioles are often present within the honeycomb areas and are recognized by a surrounding smooth muscle layer (Figure 3.3A). The enlarged airspaces contain varying amounts of mucin and admixed inflammatory cells, including neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes. Acute and chronic inflammation is common in the adjacent interstitium.

FIGURE 3.1 Classic UIP at low magnification. (A) Nonuniform appearance is seen with uneven parenchymal destruction by honeycomb change (lower left) and scars admixed with islands of nearly normal lung (upper left), so-called patchwork pattern of lung involvement. The circle surrounds a fibroblast focus (see Figure 3.6A for higher magnification). (B) More prominent scars replace alveoli in this example with adjacent islands of normal lung and a small focus of honeycomb change (top center). A fibroblast focus is circled (see Figure 3.7A for higher magnification). UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

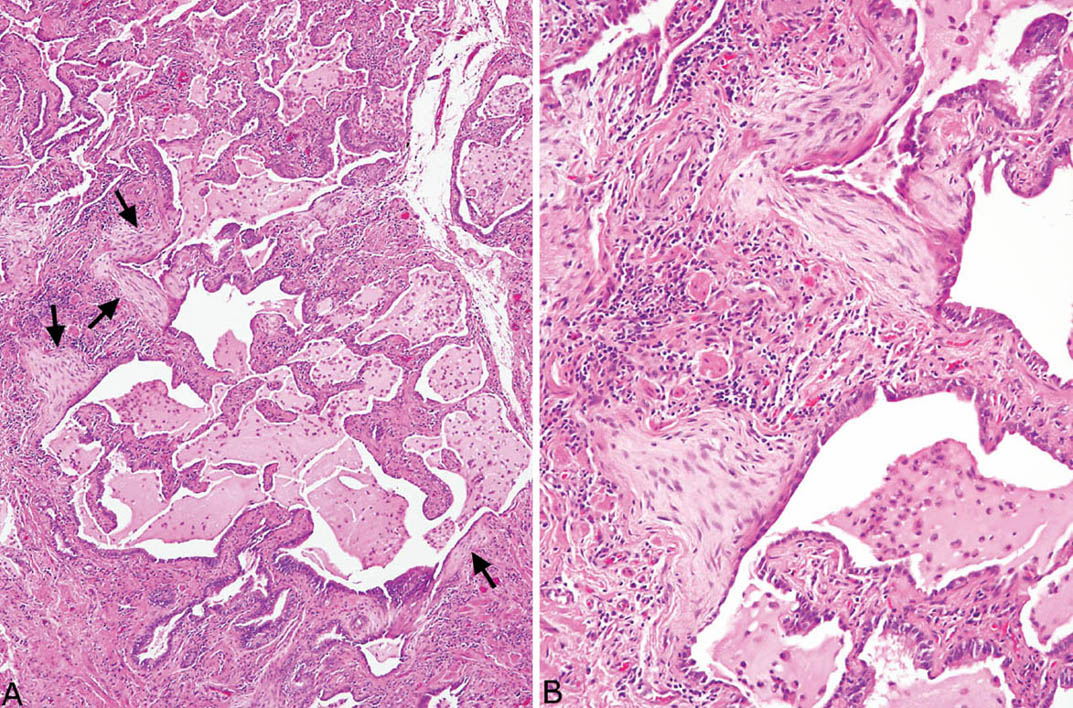

FIGURE 3.2 Honeycomb change in UIP. (A) Low magnification showing the enlarged epithelial-lined airspaces within adjacent fibrosis. Fibroblast foci are present as well (arrows), and an island of residual normal lung is seen in the lower left. The inset is a higher magnification of one of the fibroblast foci. (B) Higher magnification of honeycomb area showing mucin-containing macrophages and lymphocytes within the enlarged airspaces, which are lined by bronchiolar epithelium. There is also mild surrounding nonspecific chronic inflammation in addition to fibrosis. Note the fibroblast foci (arrows). UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

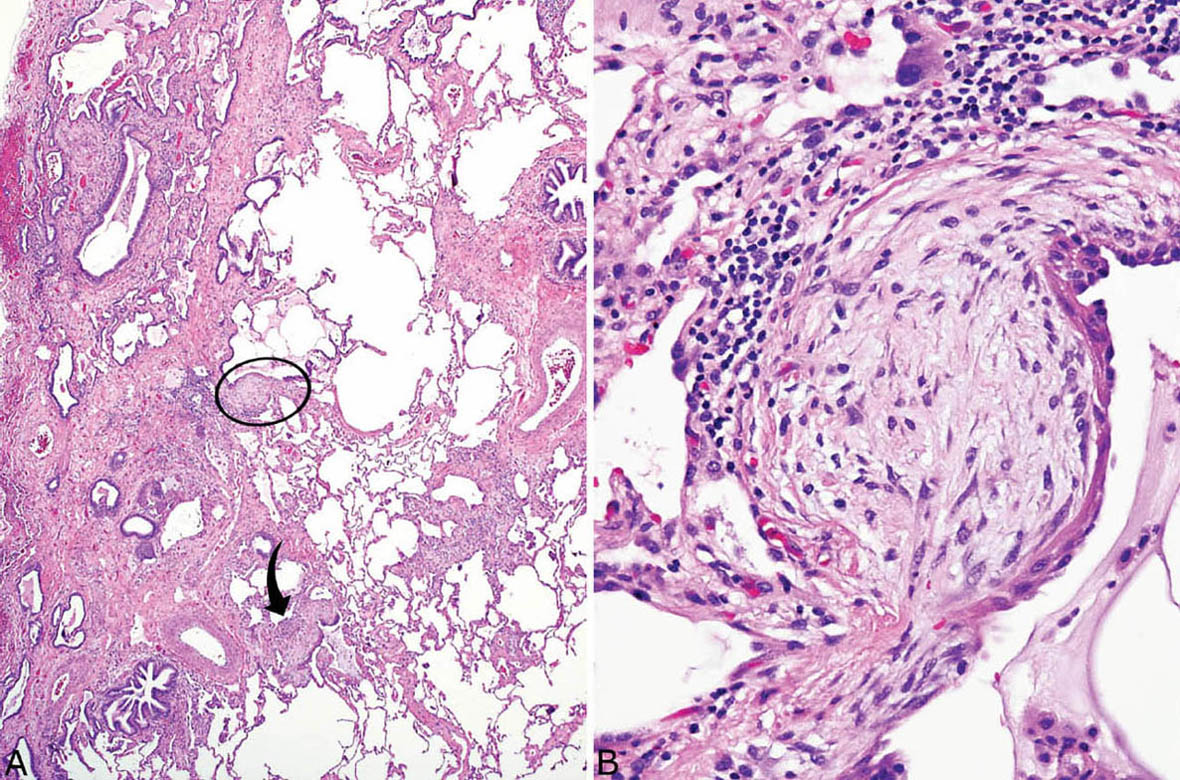

FIGURE 3.3 Honeycomb change in UIP. (A) This example shows a typical circumscribed focus of honeycomb change within densely fibrotic, scarred parenchyma. A residual bronchiole (star) with surrounding smooth muscle is present adjacent to a pulmonary artery (top left), and there are numerous fibroblast foci (arrows). (B) Higher magnification of the honeycomb spaces shows their ciliated, respiratory tract epithelial lining along with intraluminal mucin containing scattered macrophages. UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

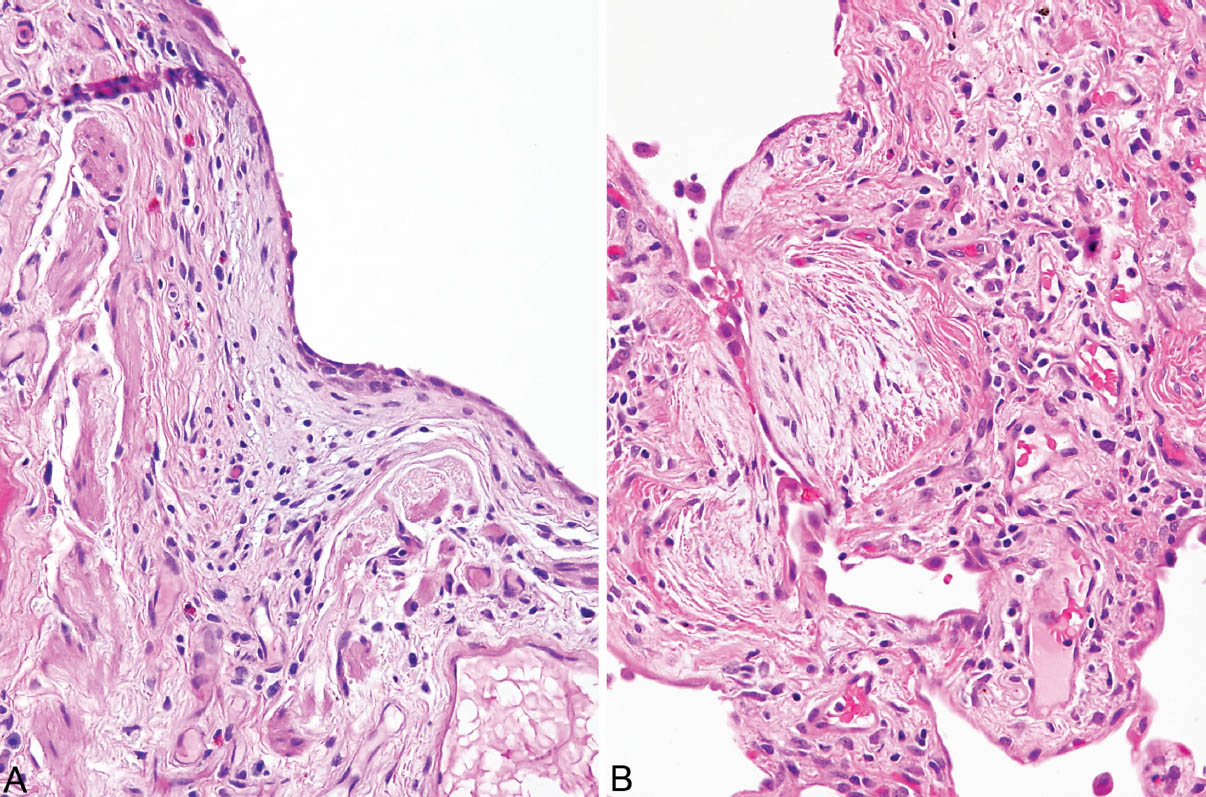

Parenchymal scars differ from honeycomb change in that they consist of rounded or angulated foci composed mainly of collagen without remnants of destroyed alveoli or restructured airspaces (Figure 3.4). Like honeycomb change, however, they replace portions of normal parenchyma. They may contain mild chronic inflammation and prominent small blood vessels. Although their appearance is different from honeycomb change, their pathogenesis is similar, and they are equally as important in indicating architectural distortion, especially in cases lacking honeycomb change. Scars also differ from ordinary interstitial fibrosis in which alveolar septa are thickened but alveolar architecture is preserved. Such areas of ordinary interstitial fibrosis are usually also present in UIP, where they are patchy and intermingle with the scars, honeycomb change, and residual normal interstitium. Bundles of hyperplastic smooth muscle are occasionally found in the honeycomb and scarred areas (Figure 3.5), and when prominent the term, “muscular cirrhosis” has been applied. They are usually associated with smoking.

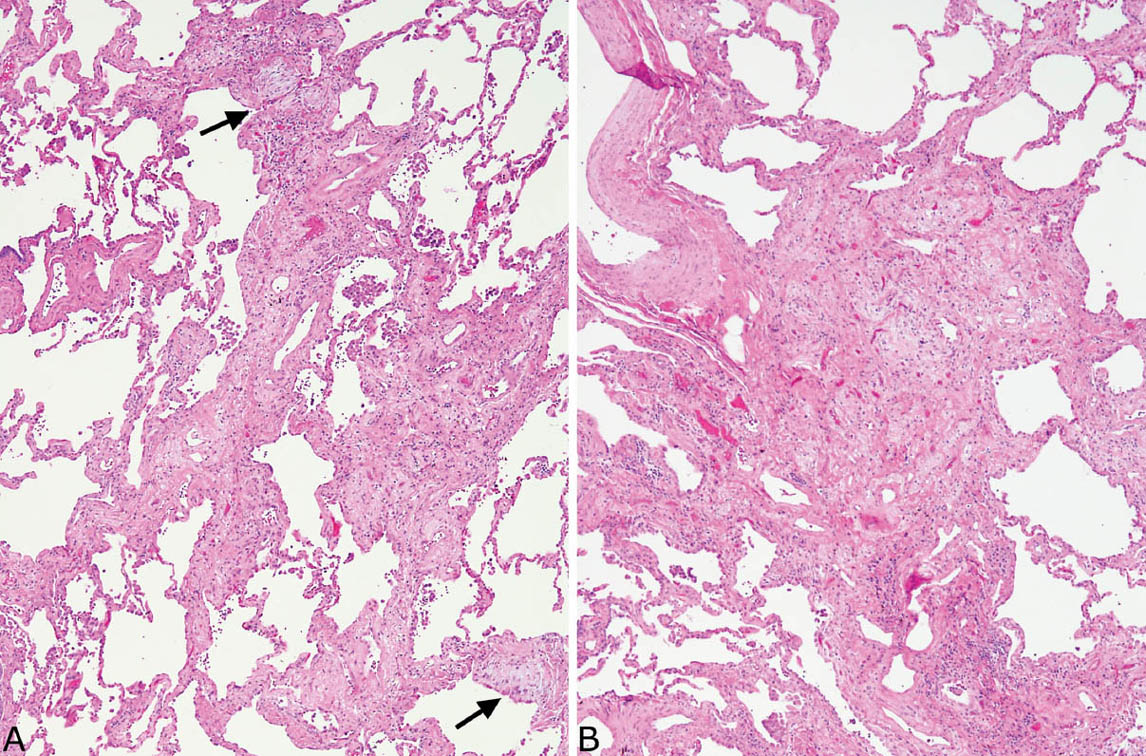

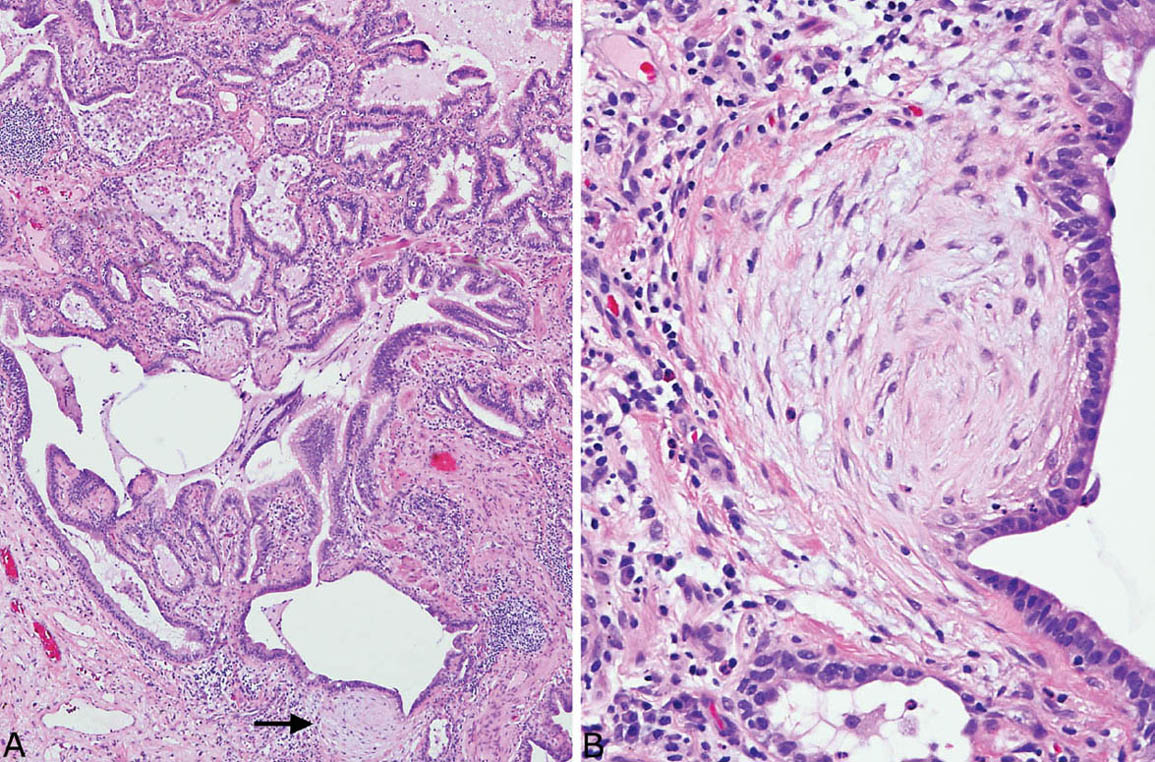

Temporal variegation is another important feature that is necessary for diagnosing UIP. It is characterized by a mixture of active, ongoing fibrosis (fibroblast foci) and chronic, inactive (collagen-type) fibrosis. Fibroblast foci occur along the interstitium, where they appear as lightly staining usually oval or elongated structures that stand out at low magnification (Figures 3.1–3.4A, 3.6, and 3.7). They are usually found in honeycomb or scarred areas (Figures 3.8 and 3.9), and they can also be found in areas of interstitial fibrosis without scarring (Figure 3.10) and occasionally even in relatively normal lung. They vary in number from case to case, being numerous in some to rare and difficult to find in others (compare Figures 3.3 and 3.9 with 3.4). They are composed of spindle-shaped fibroblasts and myofibroblasts arranged with their long axes in parallel, and they are embedded within myxoid stroma containing minimal collagen. Their luminal surface is covered by flattened or hyperplastic pneumocytes or bronchiolar epithelium and there may be associated squamous metaplasia. Mild associated chronic inflammation is often present as well.

FIGURE 3.4 Parenchymal scars in UIP. (A) Low magnification showing replacement of portions of alveoli by irregular fibrous scars in a patchwork pattern. Fibroblast foci (arrows) are easily visualized even at low magnification. Note also the incidental clusters of pigmented macrophages within airspaces that signify respiratory bronchiolitis (Chapter 11) in a smoker. (B) Higher magnification from another area showing a scar composed of collagen with scant chronic inflammation and prominent small blood vessels. UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

FIGURE 3.5 Smooth muscle hyperplasia in UIP. (A) Low magnification showing patchy scars alternating with normal lung in the characteristic patchwork pattern. Note scattered clusters of lightly pigmented macrophages within airspaces that indicate respiratory bronchiolitis and thus cigarette smoking (see Chapter 11). (B) At higher magnification, prominent hyperplastic smooth muscle bundles can be appreciated within the scars. UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

FIGURE 3.6 Fibroblast foci of UIP associated with alveolar septal fibrosis. (A) Fibroblast focus circled in Figure 3.1A. Note the elongated myofibroblasts and fibroblasts within lightly stained loose stroma. The surface is covered by a flattened epithelial layer. (B) Fibroblast focus from Figure 3.4A (bottom) covered by hyperplastic alveolar lining cells on the surface. Mild chronic inflammation accompanies the changes in both. Note the contrast between the loose stroma of the (active) fibroblast foci and the adjacent (mature, inactive) collagen deposition. UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

FIGURE 3.7 Fibroblast foci of UIP in areas of scarring. (A) Fibroblast focus circled in Figure 3.1B on the surface of a scar. Note the flattened lining cells covering the surface. (B) Fibroblast focus from Figure 3.4A (top) showing mild associated chronic inflammation and flattened surface lining cells. UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

FIGURE 3.8 Fibroblast foci in honeycomb areas of UIP. (A) Low magnification showing prominent fibroblast focus (arrow) in an area of typical honeycomb change. (B) Higher magnification of fibroblast focus showing low columnar epithelium covering the characteristic spindle cells. UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

FIGURE 3.9 Inflamed honeycomb area with fibroblast foci in UIP. (A) Low magnification showing honeycomb area with surrounding prominent chronic inflammation along with numerous macrophages within the intraluminal mucin. The fibroblast foci (arrows) are prominent even at low magnification. (B) Higher magnification showing fibroblast foci covered by flattened epithelium. Note the moderate surrounding chronic inflammation. UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

FIGURE 3.10 Fibroblast foci adjacent to honeycomb change in UIP. (A) Typical patchwork pattern of involvement of UIP changes is seen at low magnification. Fibroblast foci (circle and arrow) are seen in areas of interstitial fibrosis adjacent to scarred and honeycomb lung. A small focus of moderate interstitial inflammation is also present in this case (bottom right). (B) Higher magnification of circled fibroblast focus showing typical spindle cells beneath hyperplastic lining cells that have undergone squamous metaplasia. Chronic inflammation is prominent at the base of this fibroblast focus. UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

Fibroblast foci signify areas of acute lung injury that are undergoing organization, and they comprise the initial event in UIP. The theory is that multiple foci of microscopic acute injury occurring and recurring over many years account for the chronic progressive course with eventual scarring and honeycomb change. Not surprisingly, increased numbers of fibroblast foci tend to be associated with worse prognosis and shorter clinical course.

Fibroblast foci differ from the fibroblast plugs of organizing pneumonia (see Chapter 4) primarily by their interstitial rather than intraluminal (airspace) location. This distinction can be difficult at times, and other features helpful in their differentiation are listed in Table 3.1.

Inflammation is generally mild in UIP except for the honeycomb areas in which acute and chronic inflammation resulting from poor drainage in the altered parenchyma can be striking. Rarely, palisading histiocytes surround some honeycomb spaces and should stimulate a search of special stains for organisms. Air cysts surrounded by foreign-body giant cells are another uncommon finding in honeycomb areas, usually in patients with a history of mechanical ventilation, and they should not be confused with infectious granulomas (see Chapter 12, Figure 12.35). Interstitial chronic inflammation away from honeycomb areas may be increased in familial forms of UIP and in patients with underlying collagen vascular diseases (see subsequent section, “Collagen Vascular Disease–Associated Interstitial Fibrosis”). Lymphoid aggregates, sometimes with reactive germinal centers may be present as well and should raise suspicion of an underlying collagen vascular disease, especially rheumatoid arthritis. Occasionally, multinucleated giant cells with cholesterol crystals are observed and are nonspecific, likely related to tissue breakdown.

TABLE 3.1 Contrasting Features of Fibroblast Foci and Fibroblast Plugs

Fibroblast Foci | Fibroblast Plugs |

Occur within and along interstitium | Occur within airspaces |

Small, oval shaped to elongated | Varying size and shape (round, serpiginous, branching) |

Usually single, randomly distributed | Usually clustered in airspaces within and around small bronchioles and alveolar ducts |

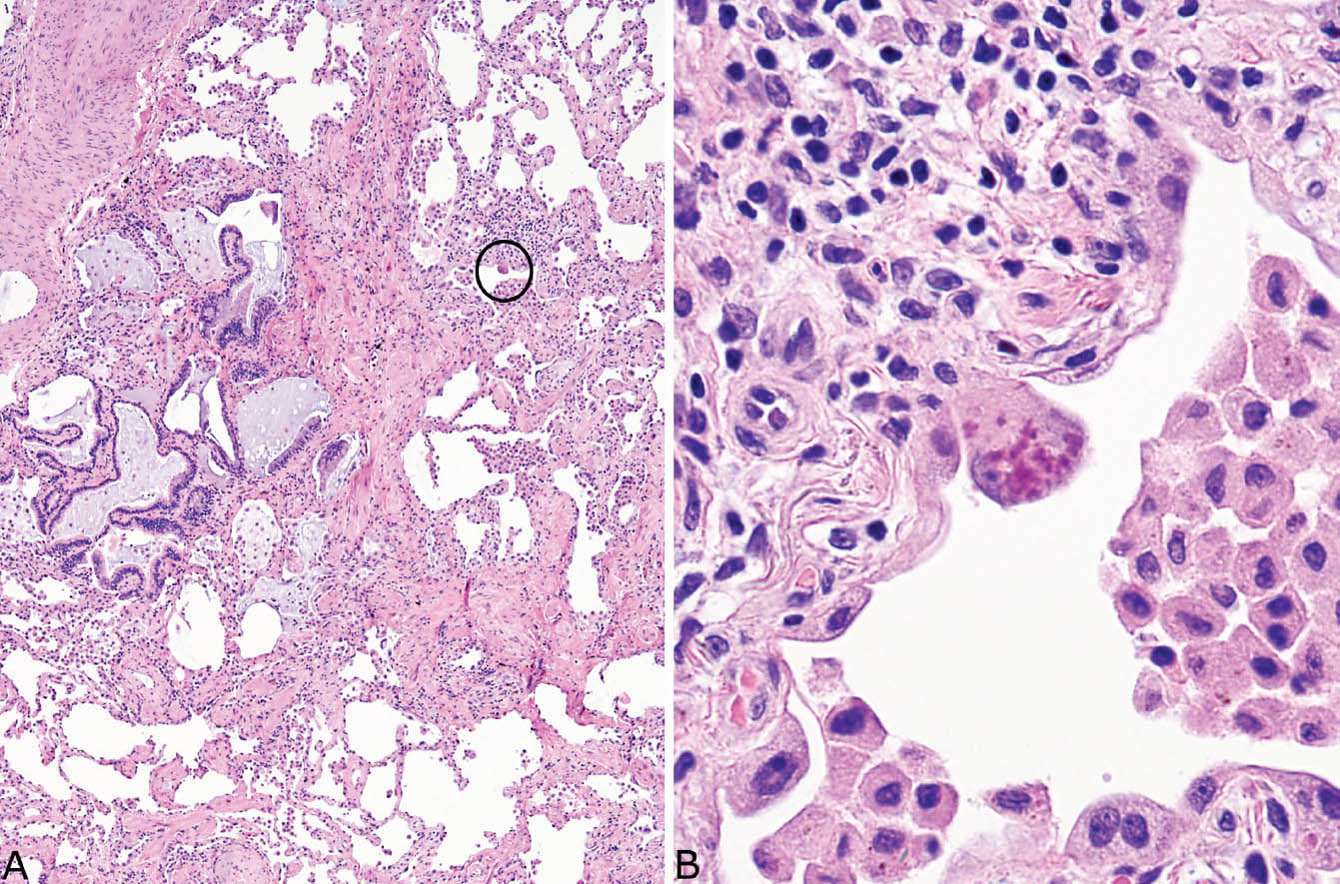

Alveolar pneumocyte hyperplasia is often prominent in the areas of alveolar septal fibrosis as in all interstitial processes. A curious finding in some cases is the presence of blurry hyaline-like material within the cytoplasm of the hyperplastic pneumocytes (Figure 3.11; see also Figure 1.15). This substance is referred to as cytoplasmic or Mallory hyaline (see Chapter 1) because of its resemblance to Mallory hyaline seen in liver disease. It is not specific to UIP, and it has no known significance in the lung.

Although the main abnormalities in UIP involve the interstitium, the alveolar spaces are not entirely free of abnormality. The most common finding is increased numbers of intra-alveolar macrophages, usually representing respiratory bronchiolitis (RB) due to cigarette smoking (see Chapter 11), and it is considered an incidental finding. Sometimes superimposed areas of organizing pneumonia (Chapter 4) or features of diffuse alveolar damage (DAD; Chapter 5) are found, and indicate acute exacerbation (see subsequent section, “Acute Exacerbation of UIP”). Small foci of airspace eosinophil and macrophage accumulation may also be seen and superficially resemble eosinophilic pneumonia (see Chapter 4) except that they are very focal and unaccompanied by other features of eosinophilic pneumonia. They have no known significance in this setting. As mentioned earlier, significant inflammation and mucin accumulation are common within honeycomb spaces and in that location have no particular significance.

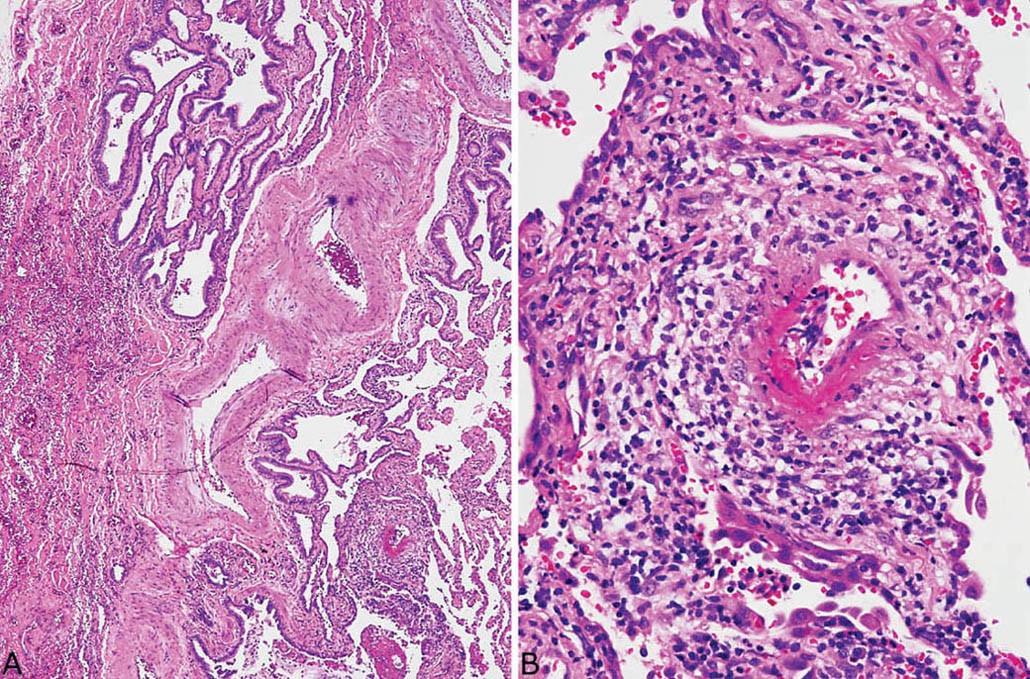

Vascular changes may also accompany other features of UIP. Most commonly, hypertensive changes, including intimal and medial hypertrophy, are found within the honeycomb areas, where they are secondary to local parenchymal destruction (see Chapter 10, Figure 10.18). If, however, the hypertensive vascular changes are found away from the end-stage lung areas, they may indicate clinically significant pulmonary hypertension. In such cases, an underlying collagen vascular disease, especially scleroderma, should be considered in the etiology. Rarely, a small-vessel vasculitis characterized by fibrinoid necrosis and chronic inflammation in small arteries and arterioles may be encountered (Figure 3.12). Patients with this finding usually have kidney involvement and are P-ANCA positive. Whether this association is coincidental or represents part of a specific syndrome is unclear.

FIGURE 3.11 Cytoplasmic (Mallory) hyaline in UIP. (A) Low magnification of otherwise typical UIP containing a single enlarged, darkly staining lining cell (circle). (B) High magnification of the cell in (A) shows a hobnail-shaped, reactive alveolar pneumocyte containing blurry, amorphous, and deeply eosinophilic material in its cytoplasm. Note the incidental smokers’ macrophages within airspaces. UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

Terminology: UIP Versus UIP Patterns

The term “UIP pattern” can be used for those few cases in which the pathologic findings resemble UIP but in which clinical evidence suggests a different disease. For example, the changes in patients with a history of inorganic or organic dust exposure or in patients receiving medications that may be associated with pulmonary fibrosis can be termed “UIP pattern.” It can also be used when other histologic features, such as granulomas or giant cells, for example, are present in addition to typical UIP changes. Usually, however, when classic pathologic changes of UIP are present, other disease entities are unlikely, and pathologists should feel comfortable diagnosing UIP.

UIP Versus Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF)

UIP is the defining pathologic finding in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, however, is a clinical term for a chronic progressive interstitial lung disease of unknown etiology, and it should not be provided as the primary pathologic diagnosis. Rather, the pathologic diagnosis should be UIP with the clinician determining whether the findings warrant inclusion as IPF.

Differential Diagnosis of UIP

A number of fibrosing interstitial lung diseases may enter the differential diagnosis of UIP, but the most common and often the most difficult to distinguish is fibrotic NSIP (see subsequent section, “Fibrotic Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonia”). Their contrasting features are listed in Table 3.2. Briefly, fibrotic NSIP lacks a patchwork pattern to the interstitial fibrosis, significant architectural distortion is not a feature, and it is usually temporally uniform without fibroblast foci. Although the distinction can be difficult when fibrosis is severe, it may not be important clinically at that stage because the prognosis in advanced disease is similarly poor.

Other forms of interstitial fibrosis may enter the differential diagnosis as listed in Table 3.3, but their distinction is usually not difficult if the main diagnostic features of UIP are remembered.

Although hypersensitivity pneumonia (HP) typically is a cellular interstitial process (see Chapter 2) that ordinarily would not be confused with UIP, rare cases as defined clinically are described that have features indistinguishable from UIP. In general, fibrotic HP should be considered in a UIP pattern only if there are prominent peribronchiolar granulomas or giant cells along with a cellular peribronchiolar interstitial infiltrate at least focally. An occasional giant cell or loose histiocyte aggregate is not sufficient, however.

FIGURE 3.12 Small-vessel vasculitis in UIP. (A) Low magnification showing typical honeycomb area of UIP at top left and abnormal blood vessel at lower right. (B) Higher magnification of the abnormal blood vessel shows fibrinoid necrosis of a portion of the vessel wall and a wide zone of surrounding chronic inflammation. UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

TABLE 3.2 Contrasting Features of Fibrotic NSIP and UIP

Histologic Feature | Fibrotic NSIP | UIP |

Patchwork pattern | Absent | Characteristic |

Architectural distortion (honeycomb change, interstitial scars) | Usually absent, never prominent | Characteristic, usually prominent |

Fibroblast foci | Usually absent, never numerous | Characteristic, usually easy to find |

NSIP, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

Clinical Features

Most patients with UIP on biopsy have IPF clinically, and for this discussion UIP and IPF are considered together. UIP/IPF is a disease of middle-aged to older adults usually between 50 and 70 years, and men are affected about twice as often as women. The disease is rare in persons younger than 40 years, and it does not occur in children. The onset is insidious with increasing dyspnea and cough, and the course is progressive and ultimately fatal in most patients. Median survival averages 2 to 6 years.

Radiographically, typical cases manifest bilateral, basilar predominant, peripheral reticular markings with traction bronchiectasis and honeycomb change noted on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT). These classic findings are present in only about half of patients, and they are considered diagnostic in the right clinical setting without the need for biopsy.

There is no known effective therapy for UIP, although recent evidence suggests that the antifibrotic agent, pirfenidone, and the tyrosine kinase inhibitor, nintedanib, may slow disease progression.

Acute Exacerbation of UIP

Although the clinical course of UIP/IPF is generally slowly progressive, some cases are marked by episodes of acute deterioration unrelated clinically to heart failure, infection, or other extraneous causes. Acute exacerbation is characterized pathologically by changes of acute lung injury, usually DAD, and less often organizing pneumonia or a combination of both superimposed on otherwise typical features of UIP (Figure 3.13). Sometimes, an acute exacerbation is the initial presentation of patients who have underlying but undiagnosed UIP, and the clinical history is acute respiratory failure. In such cases the finding of honeycomb areas within otherwise typical DAD is a clue to underlying UIP (Figure 3.14). In other cases, biopsies may contain mainly areas of honeycomb lung, and although the pathologist recognizes UIP, the DAD, which may be focal or present only at the deep edge of the biopsy, is easily missed. In such cases, the clue to diagnosis may come from the clinician who indicates that UIP does not fit with the patient’s acute presentation. Usually, with more careful review, areas of DAD can be found on the slides in addition to the UIP changes.

Helpful Tips—UIP

Do not diagnose UIP or other interstitial lung diseases in patients with radiographically localized infiltrates.

Do not diagnose UIP or other interstitial lung diseases in patients with radiographically localized infiltrates.

Be cautious in diagnosing UIP in persons younger than 50 years, and seriously question the diagnosis in persons younger than 40 years.

Be cautious in diagnosing UIP in persons younger than 50 years, and seriously question the diagnosis in persons younger than 40 years.

Inflammation may be severe in the honeycomb areas of UIP, and it should not detract from the diagnosis as long as it is confined to this area.

Inflammation may be severe in the honeycomb areas of UIP, and it should not detract from the diagnosis as long as it is confined to this area.

Acute exacerbation of UIP should be suspected when honeycomb change is seen in the background of a biopsy that otherwise shows acute lung injury changes, even when there is no history of chronic lung disease.

Acute exacerbation of UIP should be suspected when honeycomb change is seen in the background of a biopsy that otherwise shows acute lung injury changes, even when there is no history of chronic lung disease.

Look for areas of DAD in cases showing UIP microscopically but in which the clinical onset is acute.

Look for areas of DAD in cases showing UIP microscopically but in which the clinical onset is acute.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree