2

CHAPTER

![]()

Interstitial Diseases I: Cellular Variants

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a broad term that, depending on definition, may encompass a wide variety of unrelated diseases. To many clinicians, ILD includes all diseases that involve the lung diffusely, and the term is often used synonymously with “diffuse lung disease.” This approach is not practical for pathologists because lumping conditions that primarily involve airspaces together with those that mainly affect interstitial structures makes diagnosis unnecessarily difficult. A more practical approach is to separate those conditions based on morphology that predominantly affect the interstitium and, thus, represent true ILD from those that predominantly involve airspaces. It is important to remember, however, that some airspace abnormalities are present in nearly all morphologic ILDs and vice versa, and the pathologist must assess the predominant site of involvement while acknowledging that a few diseases may be difficult to categorize in this way. The sole purpose of this approach is to facilitate diagnosis for pathologists, and it is not meant to replace any other classification scheme.

To further expedite diagnosis, we have divided the ILDs into predominantly cellular (this chapter) and predominantly fibrotic (Chapter 3) variants. There may be overlapping features among some conditions, and, therefore, a few are included in both chapters. Certain other specific ILDs (pneumoconiosis, infections, for example) are reviewed in other chapters.

TOPICS

Cellular Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonia (NSIP)

Cellular Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonia (NSIP)

Hypersensitivity Pneumonia (HP)

Hypersensitivity Pneumonia (HP)

Lymphoid Interstitial Pneumonia (LIP)

Lymphoid Interstitial Pneumonia (LIP)

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH)

Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH)

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis

Lymphangiomyomatosis (LAM)

Lymphangiomyomatosis (LAM)

Diffuse Meningotheliomatosis

Diffuse Meningotheliomatosis

CELLULAR NONSPECIFIC INTERSTITIAL PNEUMONIA (NSIP)

There are two main histologic forms of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP)—cellular and fibrotic—and they are distinguished based on the predominant component. An intermediate variant in which inflammation and fibrosis are present in equal proportions was described in the early literature, but as a general rule when inflammation predominates or is equally admixed with fibrosis the changes are considered to represent cetlular NSIP. Fibrotic NSIP is diagnosed when the fibrosis predominates, and it is discussed in Chapter 3.

Histologic Features

Mild to moderate thickening of alveolar septa by an infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells

Mild to moderate thickening of alveolar septa by an infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells

Fibrosis absent or mild

Fibrosis absent or mild

Minimal, if any, architectural distortion

Minimal, if any, architectural distortion

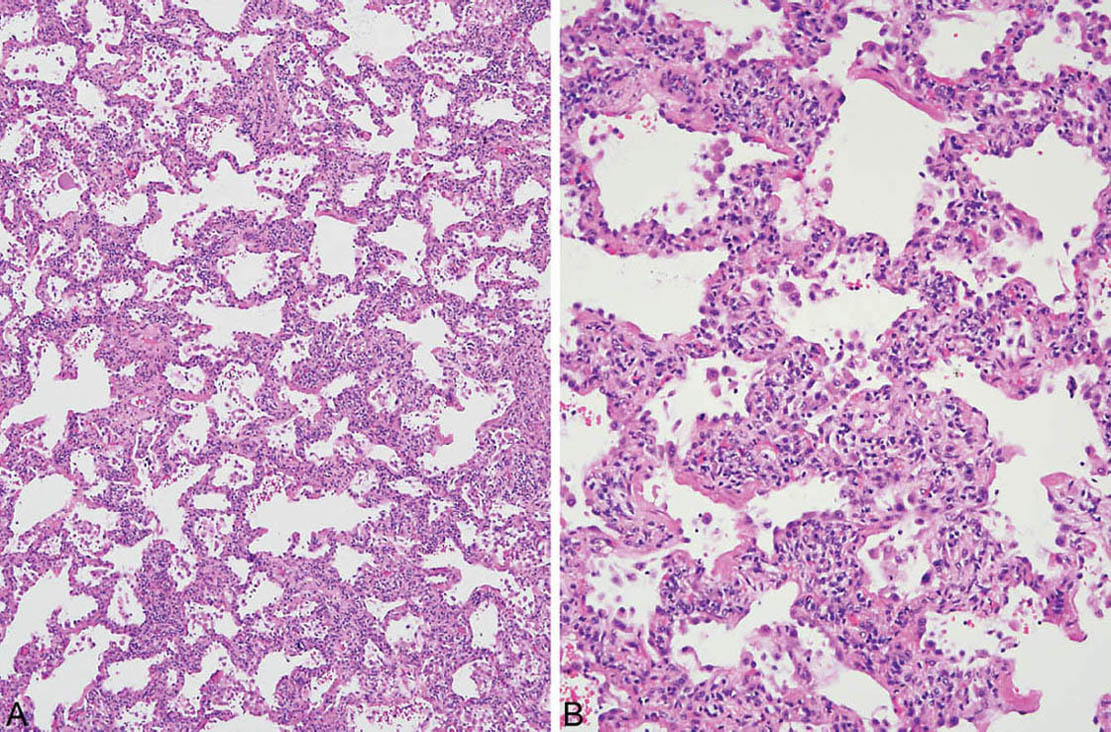

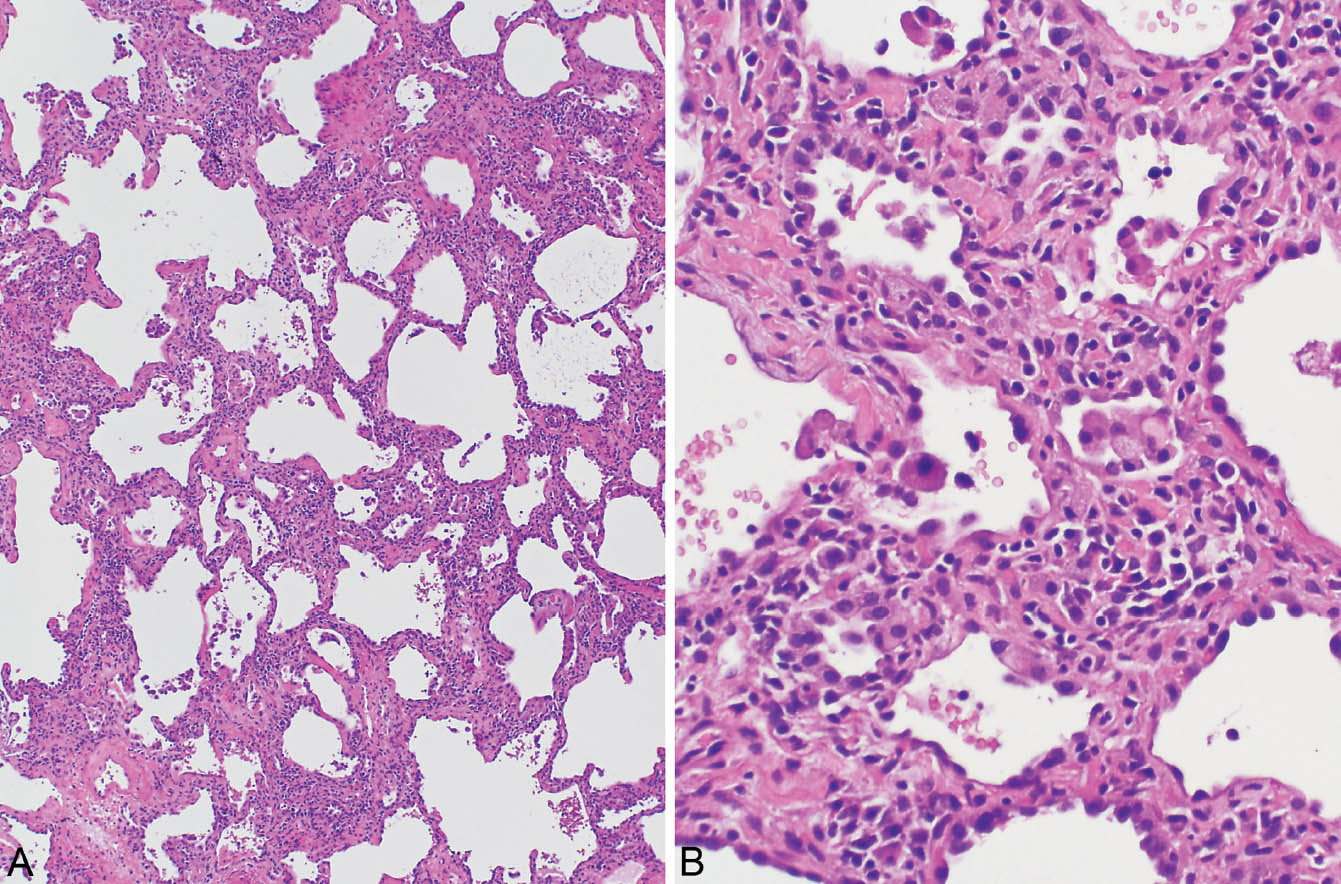

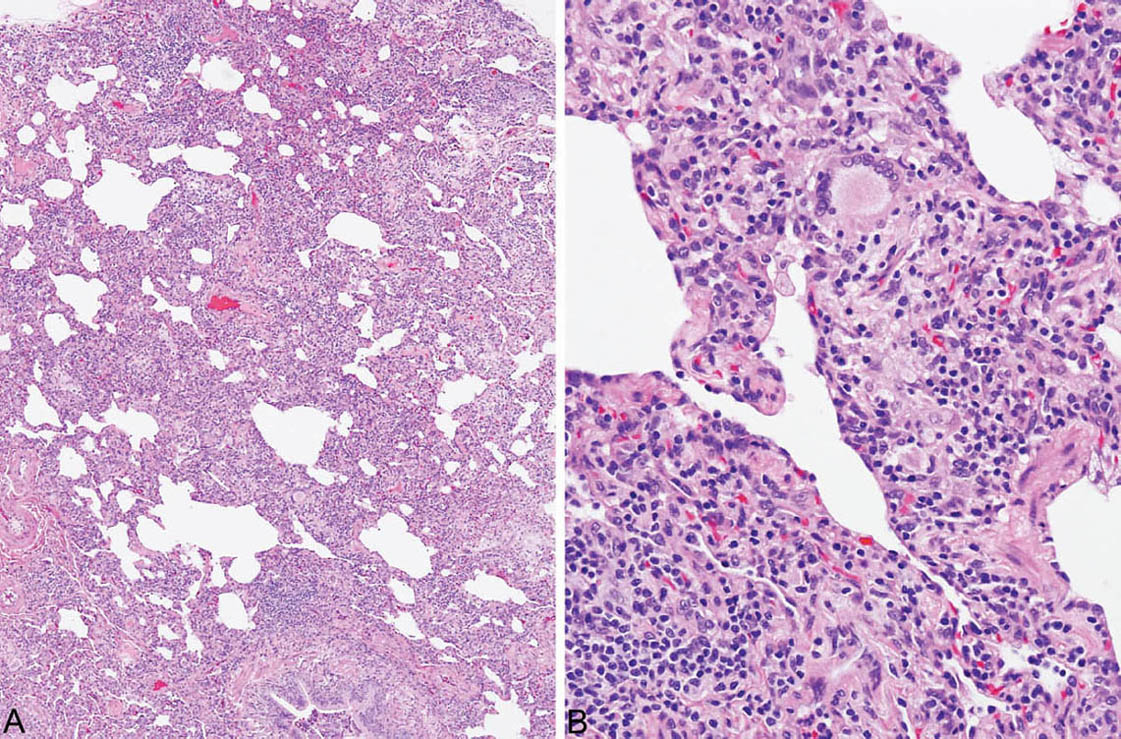

At low magnification, the process appears relatively uniform and is characterized by widening of alveolar septa by a cellular infiltrate with little, if any, architectural distortion (Figures 2.1 and 2.2). The process usually is diffuse but it may be patchy, and it is sometimes accentuated in the interstitium around bronchioles. The cellular infiltrate comprises a mixture of lymphocytes and plasma cells in variable proportions. Hyperplastic alveolar pneumocytes may be prominent along the thickened alveolar septa, thus adding to the appearance of interstitial cellularity. Some fibrosis in the form of collagen deposition may be present within alveolar septa as well (Figure 2.2), but is overshadowed by the cellular infiltrate. The appearance differs from fibrotic NSIP (Chapter 3) in which the collagen deposition predominates over inflammation (compare with Figures 3.15, 3.16, and 3.17). In cases in which inflammation and collagen are present in nearly equal amounts, the distinction of cellular and fibrosing NSIP is somewhat subjective, and although potentially of some prognostic significance, it has little influence on patient therapy.

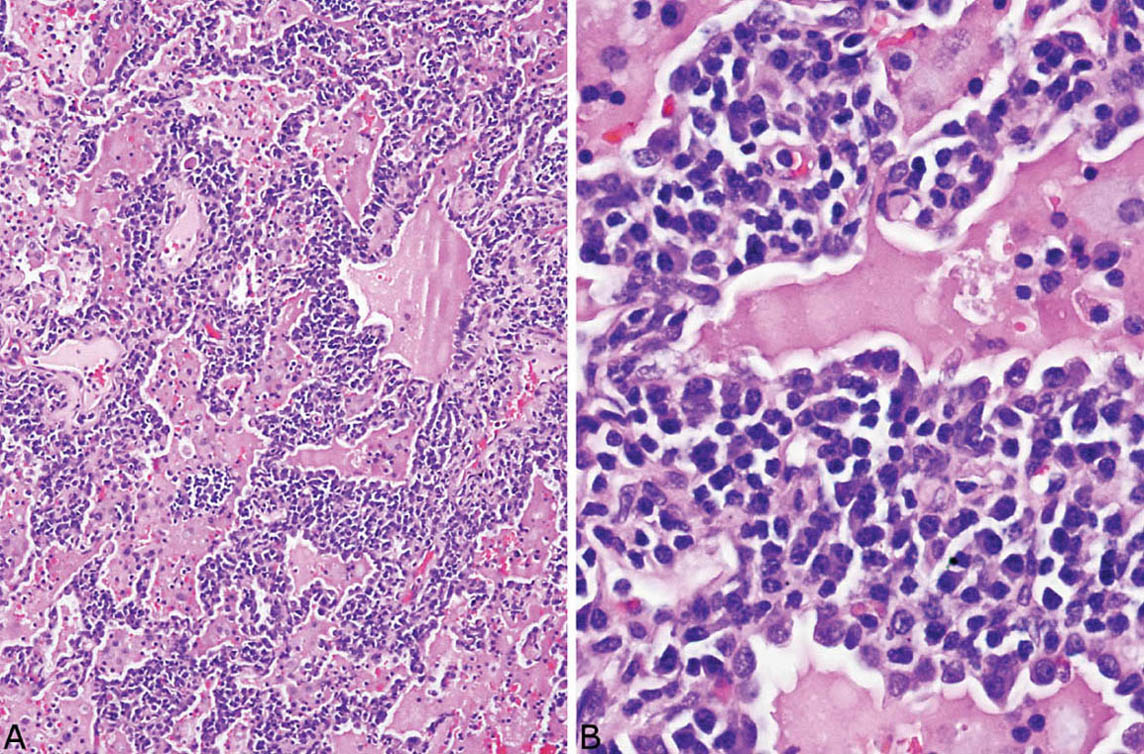

FIGURE 2.1 Cellular NSIP. (A) Uniform thickening of alveolar septa by a cellular infiltrate. (B) Higher magnification shows that the infiltrate comprises a mixture of lymphocytes and plasma cells. NSIP, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia.

FIGURE 2.2 Cellular NSIP. (A) In this case, patchy, mild, collagen-type fibrosis (top) is admixed with a cellular infiltrate. (B) Higher magnification showing lymphocytes and plasma cells admixed with some collagen in the thickened alveolar septa. Alveolar pneumocyte hyperplasia is also present and there are scattered intra-alveolar foamy macrophages. Although some fibrosis is present, the cellular infiltrate predominates. NSIP, cellular nonspecific interstitial pneumonia.

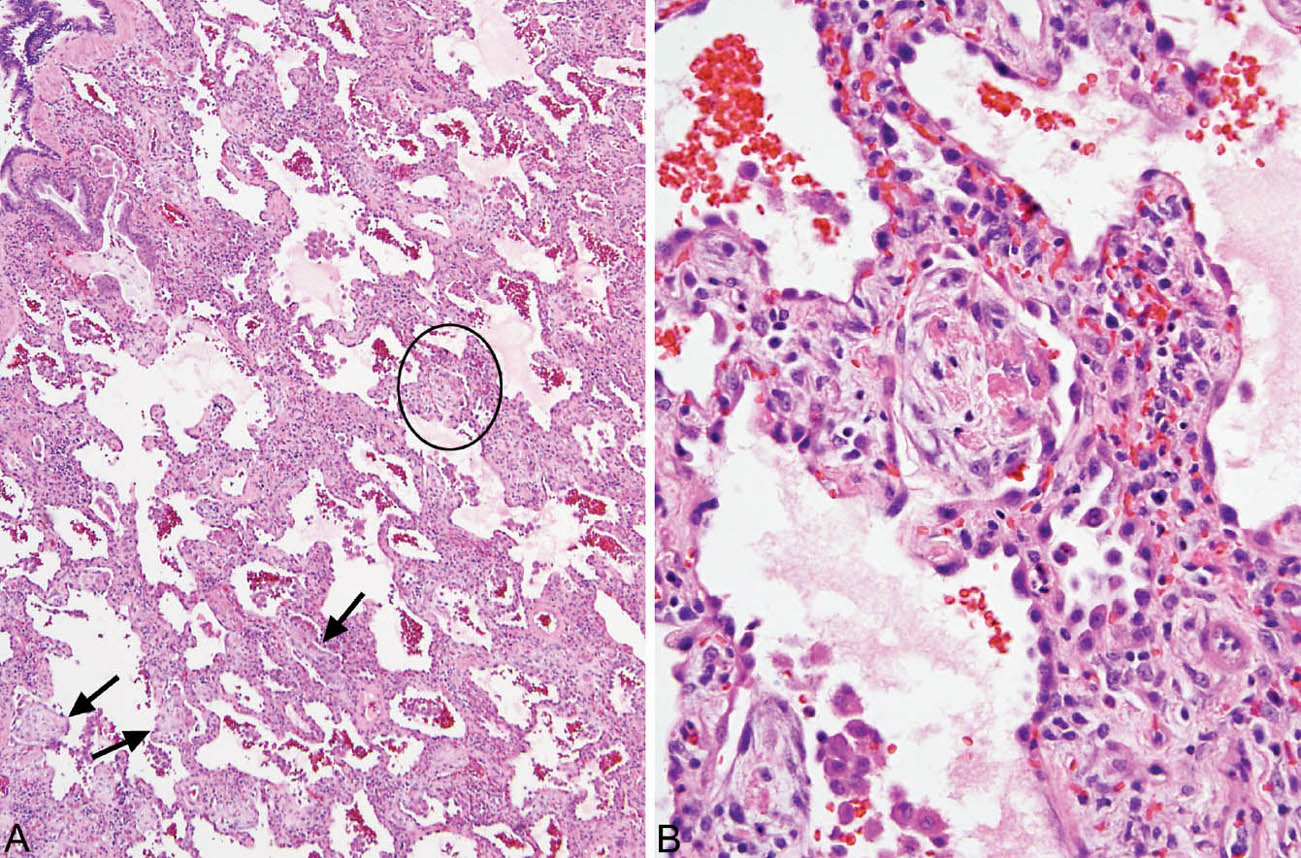

Small foci of organizing pneumonia commonly accompany the interstitial inflammation, and intra-alveolar macrophages with foamy cytoplasm may be present focally (Figure 2.3).

Pigmented macrophages, which are incidental markers of smoking (respiratory bronchiolitis, RB; see Chapter 11), may accumulate within airspaces in smokers with NSIP. In such cases, the changes should not be confused with respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease (RBILD), in which significant interstitial inflammation or fibrosis is absent (see Chapter 4).

Terminology: NSIP Versus NSIP Pattern

For clinicians, the term “NSIP” is usually interpreted as synonymous with the clinicopathologic entity of idiopathic NSIP. Identical pathologic findings, however, can be encountered in other situations, including especially underlying collagen vascular diseases, hypersensitivity pneumonia (HP), and drug toxicity. Therefore, it is preferable to use the term NSIP only in the setting of idiopathic disease, whereas the diagnosis of “NSIP pattern” is more appropriate in other settings or when clinical information is lacking. Alternatively, the descriptive term “cellular chronic interstitial pneumonia” may be used instead of NSIP pattern when clinical history is unknown or incomplete or in immunocompromised persons in whom the etiology is likely related to infection, chemotherapy, or transplantation.

Clinical Features

Cellular idiopathic NSIP is less common than fibrotic NSIP (Chapter 3) and carries a significantly better prognosis. The onset is usually insidious or subacute with dyspnea and cough occurring over several months. Adults in the fifth decade are most commonly affected, although the disease has a wide age onset and can affect children. A slight female predominance is reported in some series. Bilateral ground glass infiltrates are characteristic radiographically. The prognosis is good with a favorable response to corticosteroid therapy in most patients.

FIGURE 2.3 Cellular NSIP. (A) In this example, small foci of organizing pneumonia are present in addition to the cellular interstitial infiltrate (circle and arrows). (B) Higher magnification of the circled area showing a typical intra-alveolar fibroblast plug with some admixed fibrin deposition within an airspace adjacent to the inflamed interstium. NSIP, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia.

Helpful Tips—Cellular NSIP

Diagnose “NSIP” (rather than “NSIP pattern”) only if clinical history is supportive of idiopathic disease, and potential etiologies (such as underlying collagen vascular disease, drug reactions, or exposure sources) are excluded.

Diagnose “NSIP” (rather than “NSIP pattern”) only if clinical history is supportive of idiopathic disease, and potential etiologies (such as underlying collagen vascular disease, drug reactions, or exposure sources) are excluded.

It is best not to diagnose cellular NSIP/NSIP pattern in immunocompromised patients, as the finding in that patient population has a different connotation; use “cellular chronic interstitial pneumonia” instead.

It is best not to diagnose cellular NSIP/NSIP pattern in immunocompromised patients, as the finding in that patient population has a different connotation; use “cellular chronic interstitial pneumonia” instead.

Be cautious about diagnosing cellular NSIP/NSIP pattern on transbronchial biopsy specimens, since similar inflammatory changes are common nonspecific findings in peribronchial interstitium.

Be cautious about diagnosing cellular NSIP/NSIP pattern on transbronchial biopsy specimens, since similar inflammatory changes are common nonspecific findings in peribronchial interstitium.

HYPERSENSITIVITY PNEUMONIA (HP)

HP is an allergic reaction of the lung to inhaled antigens, usually organic dusts. It is important for the pathologist to recognize the features because continued exposure to the inciting antigen may lead to irreversible fibrosis.

Histologic Features

Cellular chronic interstitial pneumonia with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes

Cellular chronic interstitial pneumonia with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes

Bronchiolocentric distribution or accentuation

Bronchiolocentric distribution or accentuation

Frequent loose non-necrotizing granulomas and organizing pneumonia

Frequent loose non-necrotizing granulomas and organizing pneumonia

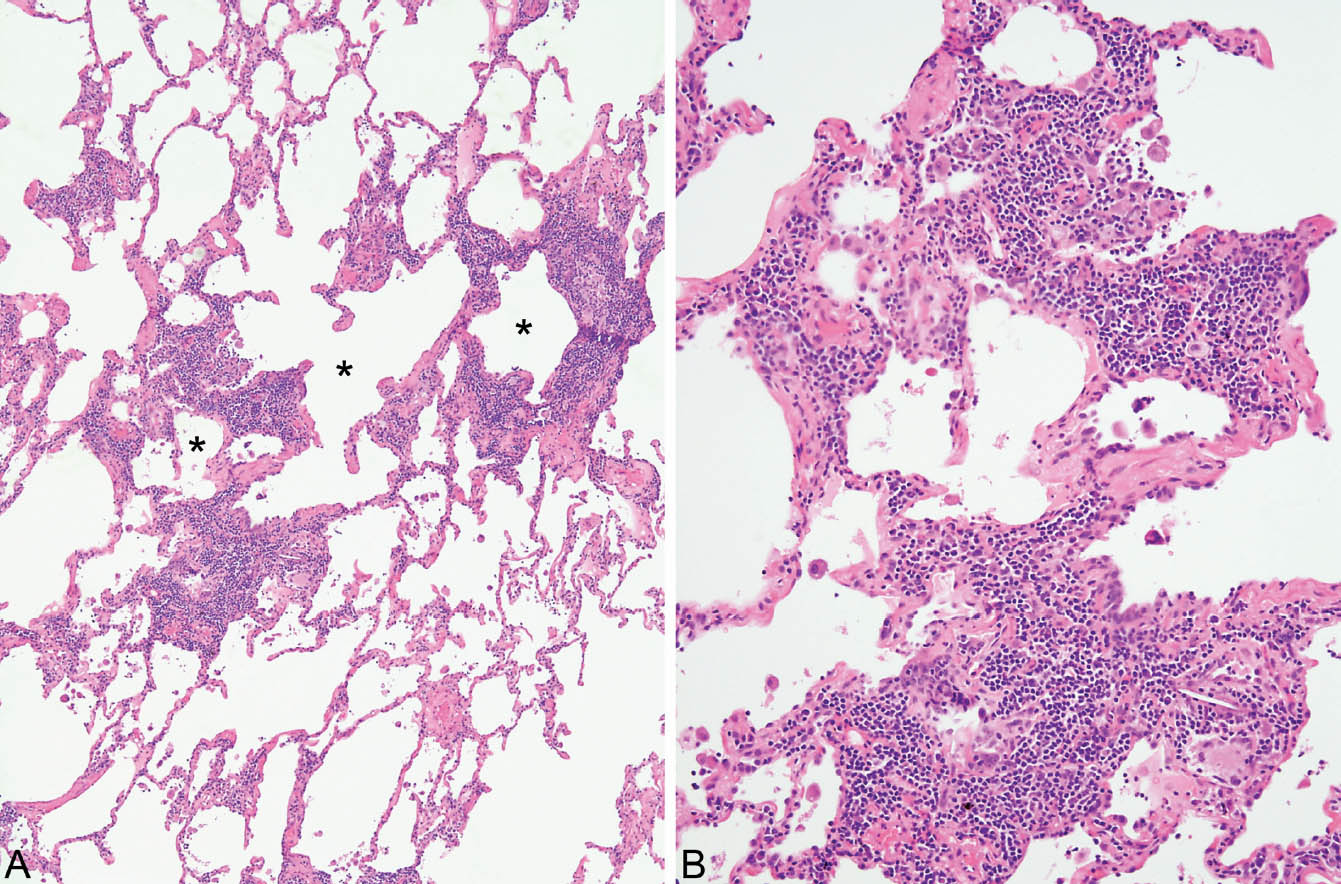

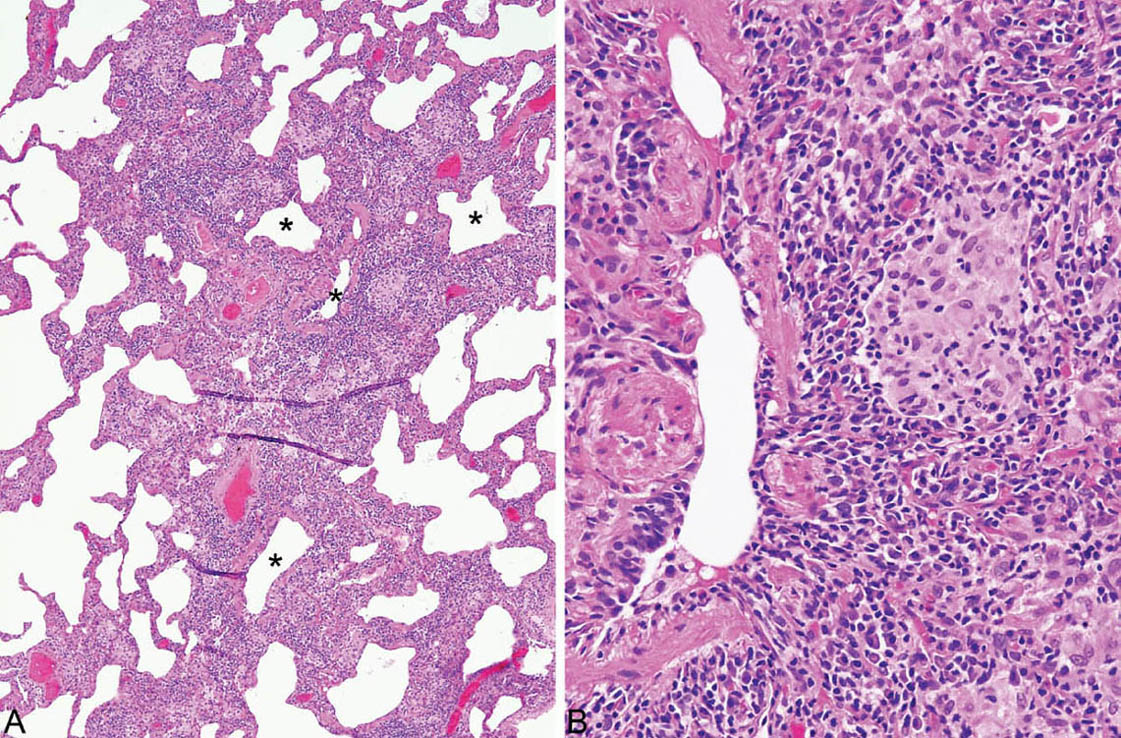

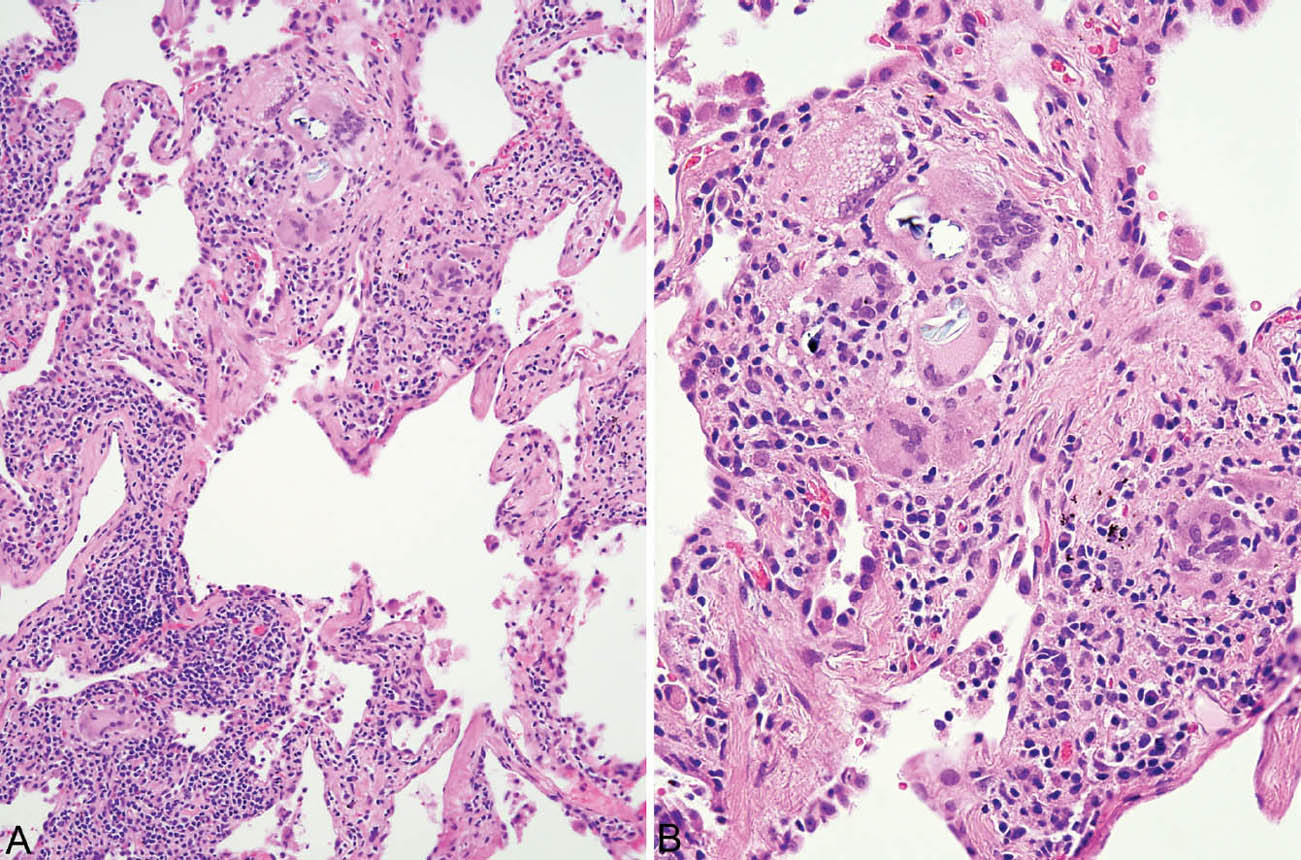

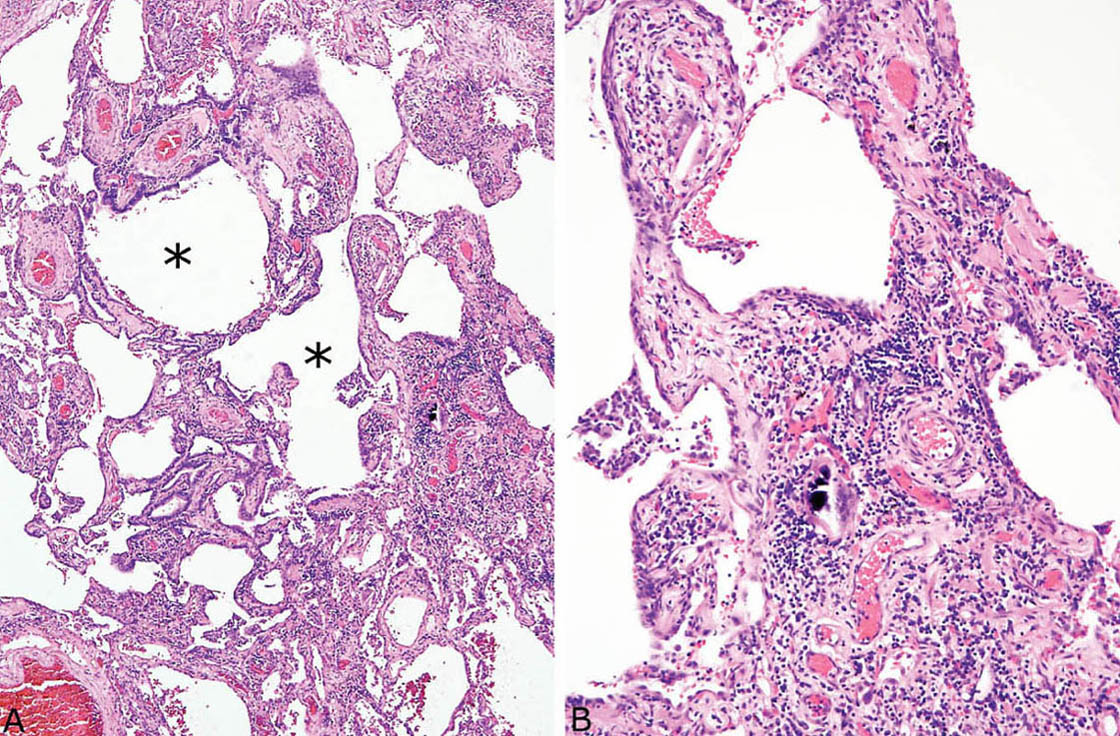

HP is characterized by a cellular chronic interstitial pneumonia that begins in peribronchiolar parenchyma and may eventually involve the lung diffusely (Figures 2.4 and 2.5). In early stages, a bronchiolocentric distribution with uninvolved distal parenchyma may be prominent (Figure 2.4), but even when the process becomes diffuse, accentuation around bronchioles can usually still be appreciated (Figure 2.6). The tip-off to diagnosis is the presence of plump epithelioid histiocytes intermingled with interstitial lymphocytes and plasma cells. The histiocytes may be present individually or may form small, loose non-necrotizing granulomas, which are most prominent around bronchioles and alveolar ducts (Figures 2.5 and 2.6). Multinucleated giant cells are common as well. Cholesterol clefts, small calcifications, and other nonspecific cytoplasmic inclusions are common in the histiocytes and giant cells (Figure 2.7). Foci of organizing pneumonia (bronchiolitis obliterans) accompany the other findings in about half the cases (Figure 2.8). Fibrosis along with some architectural distortion may be prominent in advanced, long-standing HP (Figure 2.9), and those cases may be difficult to distinguish from fibrotic NSIP and even usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP; see Chapter 3). In such cases, the bronchiolocentric accentuation of the infiltrate along with histiocytes or giant cells should suggest the diagnosis.

FIGURE 2.4 Hypersensitivity pneumonia. (A) At low magnification, a dense chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate is seen in the interstitium around alveolar ducts (stars). The more distal parenchyma is uninvolved. (B) At higher magnification, the prominent interstitial inflammatory cell infiltrate is better appreciated. It consists mainly of lymphocytes and plasma cells with scattered histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells (bottom right), one containing a cholesterol cleft.

FIGURE 2.5 Hypersensitivity pneumonia. (A) In this example, there is a diffuse cellular infiltrate involving both peribronchiolar and more distal interstitium. (B) At higher magnification, a prominent histiocytic component with an occasional multinucleated giant cell is noted along with lymphocytes and plasma cells in the interstitium adjacent to a respiratory bronchiole (lower right).

FIGURE 2.6 Hypersensitivity pneumonia. (A) Although the interstitial infiltrate in this case is diffuse, accentuation around respiratory bronchioles (stars) can still be appreciated. (B) A loose aggregate of epithelioid histiocytes is present within the infiltrate adjacent to this respiratory bronchiole.

The combination of cellular interstitial pneumonia along with bronchiolocentric distribution or accentuation and epithelioid histiocytes and/or loose granulomas is necessary for the pathologic diagnosis of HP, and the additional presence of focal organizing pneumonia further supports the diagnosis. This combination is not present in all cases, however, and some have been reported that show an NSIP pattern only, as well as, rarely, usual interstitial pneumonia. The possibility of HP should be suggested in any cellular bronchiolocentric interstitial pneumonia, although a bronchiolocentric distribution is not specific, and further clinical evaluation in such cases is necessary to establish the diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

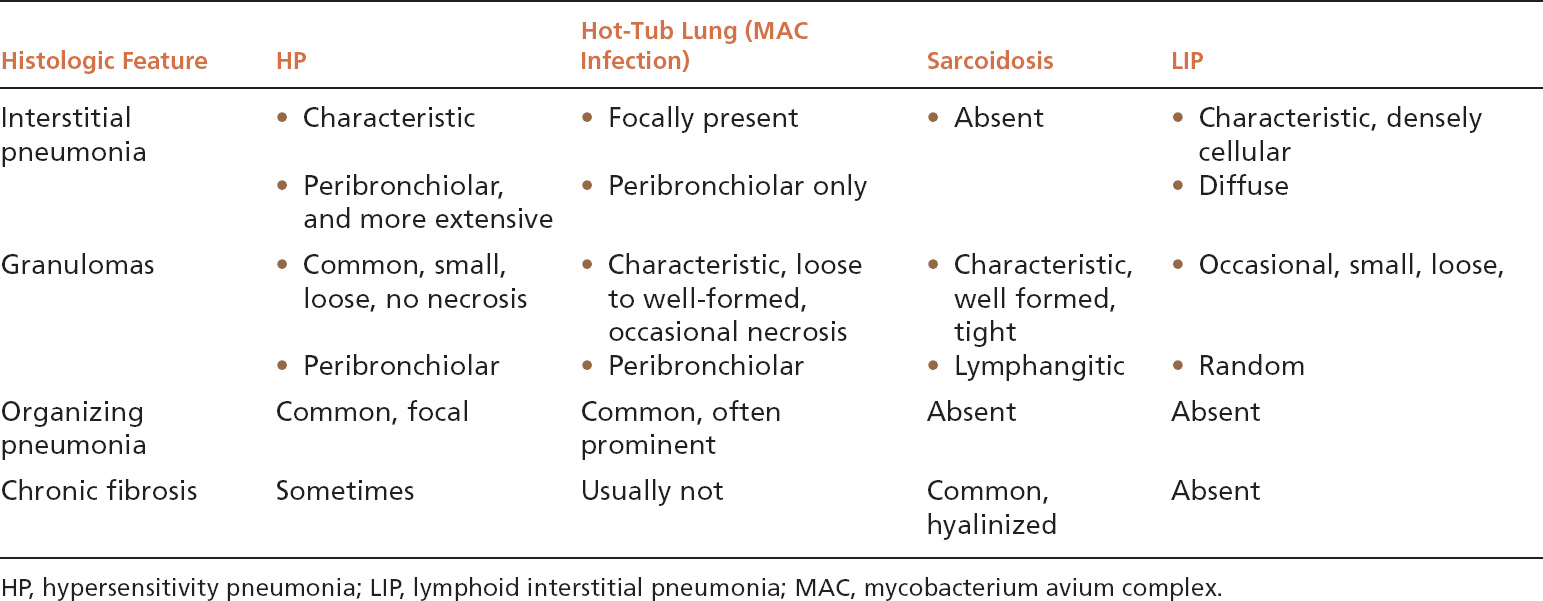

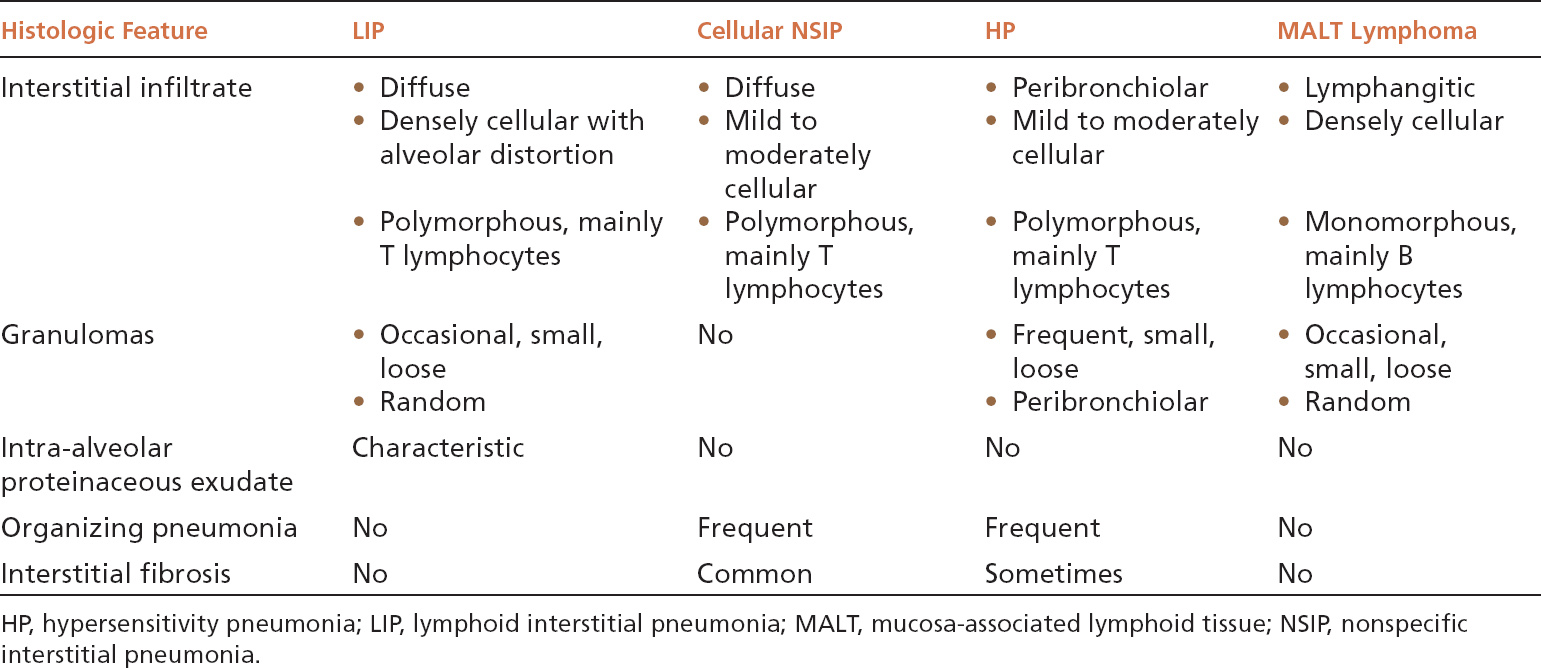

Because granulomas are often present in HP, other granulomatous lung diseases may enter the differential diagnosis (Table 2.1). Sarcoidosis (see subsequent section, “Sarcoidosis”) is usually mentioned as an important lesion in the differential diagnosis, but if it is remembered that HP is primarily a cellular interstitial pneumonia with small, loose granulomas, the distinction is not difficult. In sarcoidosis, there is no interstitial pneumonia, the granulomas are tight and well formed, and their distribution is lymphangitic rather than peribronchiolar. Furthermore, airspace lesions do not occur in sarcoidosis, whereas foci of organizing pneumonia are common in HP. Most granulomatous infections, likewise, are not difficult to distinguish from HP because necrotizing granulomas are usually present without an interstitial pneumonia, and organisms are easily identifiable in special stains. One exception is mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) infection, which can cause a combination of interstitial pneumonia, granulomas, and organizing pneumonia similar to HP. Most MAC infections are related to hot-tub exposure, and thus are termed hot-tub lung (see Chapter 8, Figure 8.16). Whether hot-tub lung is a form of HP or a true infection is debatable. It differs from HP, however, in that the granulomas tend to be larger and well circumscribed sometimes containing necrosis, and the interstitial pneumonia does not extend beyond the peribronchiolar parenchyma. Certain infections in immunocompromised persons may also mimic HP, and in this setting special stains for organisms should be carefully examined. The diagnosis of HP should not be seriously considered in immunocompromised persons unless there is a strong supporting clinical history. Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP) (see subsequent section, “Lymphoid Interstitial Pneumonia”) also enters the differential diagnosis because histiocytes and loose granulomas may occur in the interstitial infiltrate. It differs in that it lacks both bronchiolocentric accentuation and organizing pneumonia areas, and the interstitial infiltrate is more densely cellular.

FIGURE 2.7 Hypersensitivity pneumonia. (A) Loose non-necrotizing granuloma (top) and scattered multinucleated giant cells are present along with chronic inflammatory cells in the interstitium around this respiratory bronchiole. (B) A higher magnification view shows nonspecific cytoplasmic inclusions within some giant cells representing metabolic breakdown products. Some may be birefringent under polarized light.

FIGURE 2.8 Hypersensitivity pneumonia. (A) A densely cellular infiltrate is present in the interstitium around an alveolar duct (star). At the top, adjacent airspaces are partially filled fibroblast plugs of organizing pneumonia, shown at higher magnification in (B). An area of loose granulomatous inflammation is also present in the area of organizing pneumonia and is shown at higher magnification in (C).

FIGURE 2.9 Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonia. (A) In this example, considerable fibrosis with mild architectural distortion is appreciated at low magnification, although interstitial cellularity is maintained surrounding respiratory bronchioles (stars). (B) Higher magnification showing a multinucleated giant cell with calcified cytoplasmic inclusion in the cellular infiltrate.

TABLE 2.1 Contrasting Histologic Features of HP and Other Inflammatory and Granulomatous Processes

Clinical Features

Hypersensitivity pneumonia is an immunologic reaction to inhaled antigens, including most often bacterial, animal protein, and fungal (Table 2.2). The onset can be acute, subacute, or chronic. The acute form is well recognized clinically because it follows known exposure to an antigen within a few hours, and biopsy is not necessary for diagnosis. Both the subacute and chronic forms may come to biopsy because the relation of the disease to an exposure source may not be obvious clinically. Symptoms may occur over weeks or months and include fever and shortness of breath in subacute disease, whereas the chronic form has a more insidious onset with shortness of breath and cough occurring over months. Bronchoalveolar lavage usually shows lymphocytosis with CD8 predominance. The radiographic changes vary from ground glass and nodular infiltrates early to reticular interstitial markings often with air trapping and sometimes honeycomb change in long-standing cases. The process usually has an upper lobe predominance, which may help in the radiologic differential diagnosis. Although most patients respond to corticosteroid therapy, the optimal therapy is to remove the offending antigen from the patient’s environment or vice versa. Irreversible fibrosis may develop with continued exposure. Identifying the inciting antigen may be difficult, however, as laboratory tests are not entirely specific, and inhalation challenge with a presumed antigen is usually not practical.

TABLE 2.2 Common Causes of HP

Thermophilic bacteria | Moldy hay (farmer’s lung) Air conditioners (air conditioner lung) Humidifiers (humidifier lung) |

Bird proteins | Droppings, feathers (pigeon breeder’s disease, bird fancier’s lung) |

Fungi (Trichosporon cutaneum, Cryptococcus albidus) | Home environment (summer-type HP—Japan) |

Other bacteria (Pseudomonas, acinetobacter, nontuberculous mycobacteria) | Metal working fluid (machine operator’s lung) |

Chemicals (trimellitic anhydride, methylene diisocyanate, toluene diisocyanate) | Plastics, rubber manufacturing (chemical worker’s lung) |

HP, hypersensitivity pneumonia.

Helpful Tips—HP

A bronchiolocentric distribution includes accentuation of the process around alveolar ducts as well as bronchioles, and, therefore, a bronchiole may not be visible in the center of a bronchiolocentric infiltrate. Sometimes even alveolar ducts are not identified, and bronchiolocentricity is identified by proximity to a pulmonary artery, which normally is accompanied by an alveolar duct or bronchiole.

A bronchiolocentric distribution includes accentuation of the process around alveolar ducts as well as bronchioles, and, therefore, a bronchiole may not be visible in the center of a bronchiolocentric infiltrate. Sometimes even alveolar ducts are not identified, and bronchiolocentricity is identified by proximity to a pulmonary artery, which normally is accompanied by an alveolar duct or bronchiole.

An exposure source may not be identifiable even in cases with classic pathologic findings.

An exposure source may not be identifiable even in cases with classic pathologic findings.

HP should not be a strong consideration in immunocompromised persons, because, in that setting, the changes most often are due to infection or occasionally to drug (methotrexate) toxicity.

HP should not be a strong consideration in immunocompromised persons, because, in that setting, the changes most often are due to infection or occasionally to drug (methotrexate) toxicity.

LYMPHOID INTERSTITIAL PNEUMONIA (LIP)

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP) is a rare interstitial pneumonia that is most commonly associated with underlying immunodeficiency or collagen vascular diseases. Some cases reported as LIP in the past were unrecognized low-grade (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue [MALT]) lymphomas.

Histologic Features

Densely cellular chronic interstitial pneumonia composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells in variable proportions sometimes accompanied by histiocytes and loose granulomas

Densely cellular chronic interstitial pneumonia composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells in variable proportions sometimes accompanied by histiocytes and loose granulomas

Marked widening of alveolar septa by the interstitial infiltrate with compression and distortion of alveolar spaces

Marked widening of alveolar septa by the interstitial infiltrate with compression and distortion of alveolar spaces

Proteinaceous exudate often present in alveolar spaces

Proteinaceous exudate often present in alveolar spaces

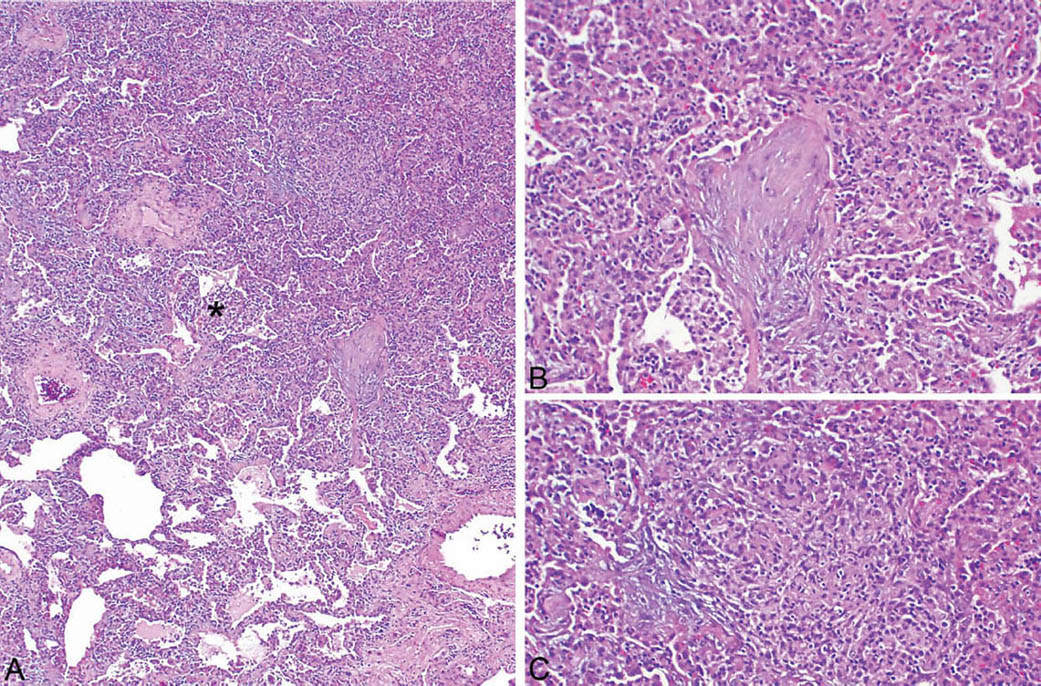

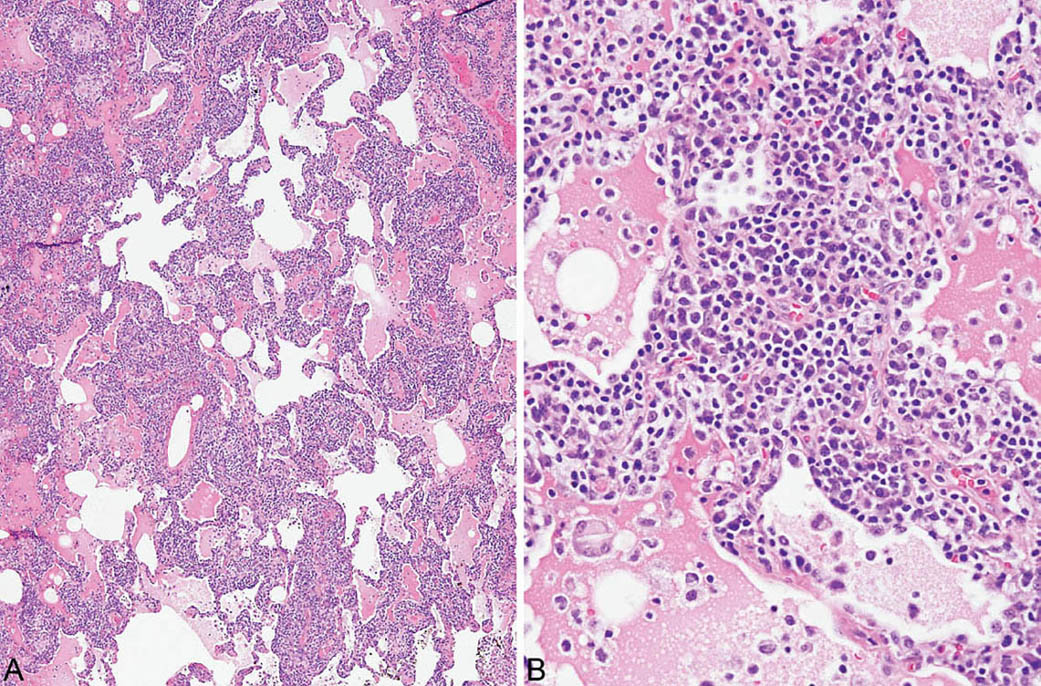

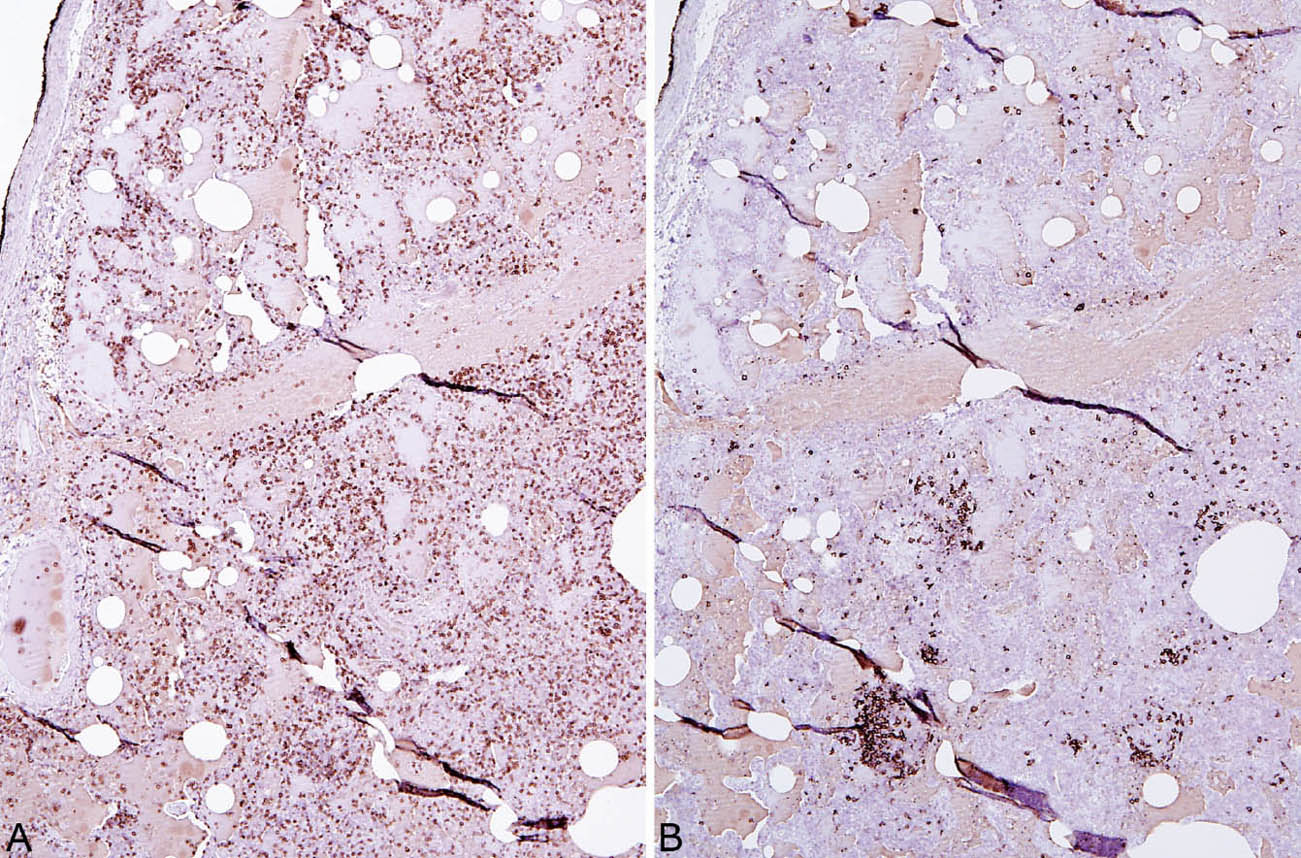

LIP is characterized by a densely cellular interstitial infiltrate composed of a mixture of small lymphocytes and mature plasma cells in variable proportions with minimal, if any, fibrosis (Figure 2.10). Occasional lymphoid follicles with germinal centers may be present. The lymphocytes are predominantly CD3-positive T-cells with only scattered CD20-positive B-cells except in germinal centers, and the plasma cells are polyclonal (Figure 2.11). The process is diffuse without any specific localization. Alveolar septal widening by the interstitial infiltrate may be so striking that adjacent alveolar spaces appear compressed or otherwise distorted. A proteinaceous exudate that stains deeply eosinophilic is commonly present within adjacent alveolar spaces, and there may also be scattered intra-alveolar lymphocytes and macrophages (Figure 2.12). Sometimes epithelioid histiocytes either individually or in small aggregates are focally admixed with the interstitial lymphocytes and plasma cells, but well-formed granulomas are not seen (Figure 2.13). Organizing pneumonia is not a feature.

FIGURE 2.10 Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia. (A) At low magnification, there is marked, relatively uniform alveolar septal thickening by a dense cellular infiltrate. (B) A higher magnification highlights the characteristic mixture of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Note the prominent eosinophilic proteinaceous exudate present within some adjacent airspaces.

Clinical Features

LIP is a rare interstitial pneumonia. It tends to affect middle-aged adults, although it also occurs in children with HIV infection in whom it is considered a marker of AIDS. Dyspnea and cough are common presenting complaints. Radiographically, there is a spectrum of changes including most commonly diffuse ground glass and reticulonodular opacities. Nodules and cysts have also been described. In adults, LIP is often associated with underlying diseases such as Sjogren syndrome and other collagen vascular diseases as well as certain immunodeficiency states such as common variable immunodeficiency. The clinical course is variable, depending on the underlying condition, with some patients responding to corticosteroid therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

The main lesion in the differential diagnosis of LIP is a low-grade, extra-nodal marginal zone B-cell (MALT) lymphoma (Table 2.3). MALT lymphomas contain predominantly monomorphous infiltrates of small lymphocytes that follow a lymphangitic distribution. Although plasma cells and histiocytes and even small granulomas or abortive germinal centers may also occur, they usually are focal findings. The small lymphocytes are predominantly B-cells and stain positively with CD20 in contrast to CD3-positive T lymphocytes that predominate in LIP, and B-cell gene rearrangements can usually be identified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques. When plasma cells are prominent, immunohistochemistry or in situ hybridization for kappa and lambda light chains can be used to assess clonality.

FIGURE 2.11 Lymphoid phenotype in LIP. (A) The majority of lymphocytes stain positively as T-cells (CD3 immunostain) whereas (B) there are only scattered B-cells (CD20 immunostain). Most of the B-cells are present in small germinal centers. LIP, lymphoid interstitial pneumonia.

FIGURE 2.12 Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia. (A) This low-magnification view shows the characteristic dense interstitial cellular infiltrate and resultant distorted and angulated alveoli. A prominent proteinaceous exudate containing scattered macrophages and lymphocytes is present within the airspaces. (B) Higher magnification shows the typical densely cellular mixture of plasma cells and lymphocytes causing marked thickening of alveolar septa.

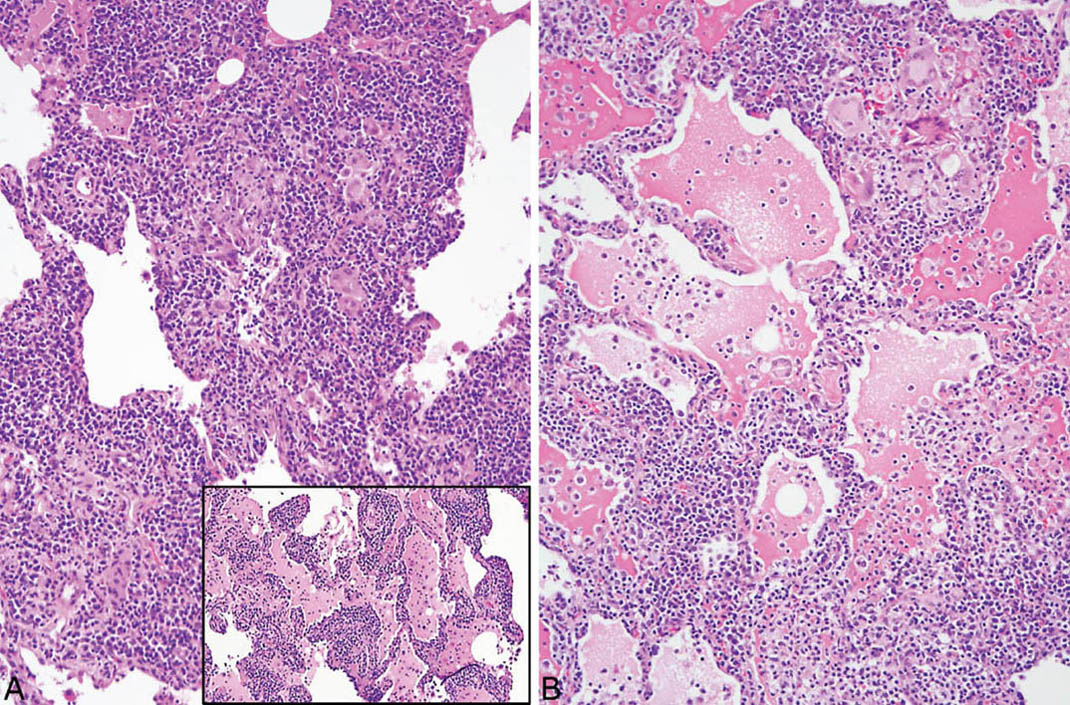

FIGURE 2.13 Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia. (A) In this example, scattered epithelioid histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells are focally admixed with the dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and there are occasional loose granulomas (B, top right). Note also the distortion of alveoli by the marked interstitial infiltrate. Inset in (A) is a low-magnification view from the same case showing the typical dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate without histiocytes or granulomas that comprised most of the infiltrate in other areas.

TABLE 2.3 Contrasting Features of LIP and Other Cellular Interstitial Processes

Both cellular NSIP and classic HP enter the differential diagnosis of LIP as well, and their contrasting features are summarized in Table 2.3. The most important features in the differential diagnosis include the greater density of the infiltrate in LIP and the resultant marked alveolar septal widening and distortion without fibrosis. Although loose granulomas may occur in LIP, they are randomly distributed rather than peribronchiolar as in HP. The intra-alveolar proteinaceous exudate is characteristic of LIP and not usually seen in the other entities.