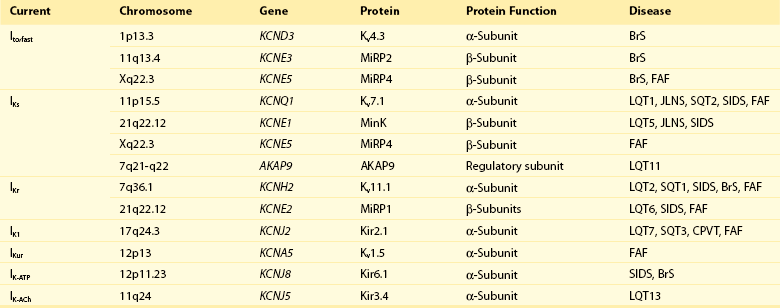

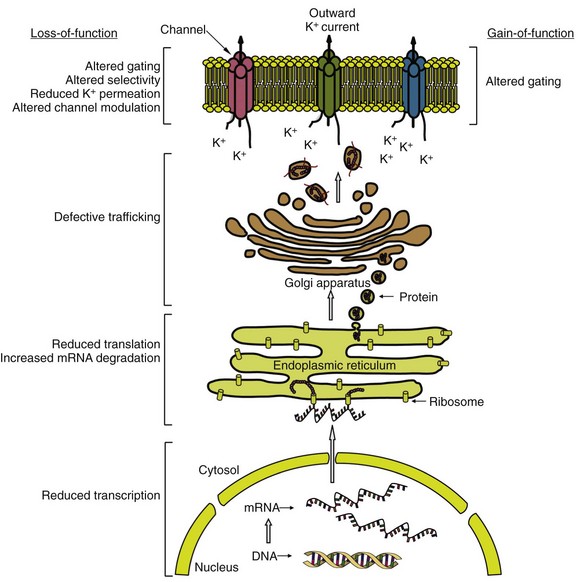

51 Potassium (K+) channels are necessary for proper functioning of cardiac myocytes and many other human cell types. In the mid-1990s, the human ether-a-go-go related gene (HERG; now referred to as KCNH2) and KVLQT1 (now referred to as KCNQ1), each encoding for a major cardiac K+ channel, were among the first genes linked to an inheritable arrhythmia syndrome.1,2 Ever since, many other genes encoding for cardiac K+ channels or their accessory (regulatory) subunits have been implicated in the etiology of various inheritable arrhythmia syndromes, including the long QT syndrome, the short QT syndrome, sudden infant death syndrome, catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, the Brugada syndrome, and familial atrial fibrillation (Table 51-1).3 A detailed description of the molecular biology and physiology of cardiac K+ channels is provided elsewhere in this book. This chapter focuses on the molecular genetics of inheritable diseases related to cardiac K+ channels, so-called K+ channelopathies. Clinical features and management of these diseases are described in detail elsewhere in this book. The long QT syndrome (LQTS) is a cardiac arrhythmogenic disease that causes syncope and sudden death due to torsades de pointes, a characteristic form of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, and ventricular fibrillation. Inheritable (congenital) LQTS is characterized by a prolonged heart rate corrected QT interval (QTc duration) on a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) due to a delay in repolarization of the ventricles, in the absence of structural heart diseases or secondary causes of a prolonged QTc duration, such as electrolyte abnormalities, hypothermia, and use of certain drugs. Inheritable LQTS with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance has an estimated prevalence of 1 : 2500, and is traditionally called the Romano-Ward syndrome (first described independently by the Italian pediatrician Cesarino Romano in 1963 and the Irish pediatrician O. Connor Ward in 1964). The very rare autosomal recessive form of LQTS, with concomitant congenital bilateral sensory neural deafness, is called the Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome (first described by Anton Jervell and his associate Fred Lange-Nielsen in 1957).3 The autosomal dominant form is subdivided into different subtypes (so far 13 subtypes) according to the affected gene. The subdivision is based on the chronological order in which the subtypes are reported. This subdivision, which is based on underlying molecular genetic and pathophysiological mechanisms, is not ideal, but is followed in this chapter. Four subtypes of LQTS (LQT1, LQT2, LQT7, and LQT13) are linked to mutations in genes encoding for the pore-forming α-subunits of voltage-gated cardiac K+ channels (Kv channels), and three subtypes (LQT5, LQT6, and LQT11) are linked to mutations in genes encoding for one of the regulatory subunits of Kv channels. Most mutations involve single-nucleotide substitutions in the coding regions (exons) of genes that alter a codon, leading to the replacement of one amino acid by a different one (missense mutations; approximately two-thirds of all mutations) or the creation of an early (premature) stop codon resulting in the formation of a truncated protein (nonsense mutations). Single-nucleotide substitutions in the noncoding regions (introns) also occur and may result in altered gene transcripts. Specific intronic nucleotide sequences at the intron/exon (acceptor site) and exon/intron (donor site) boundaries are crucial for the process whereby introns are excised from gene transcripts to create mature protein-encoding mRNAs (i.e., the splicing process). Mutations within these highly conserved intronic regions may cause aberrant splicing, leading to the deletion of entire exons (or exon parts) or inclusion of entire introns (or intron parts) in the mature mRNA, thereby often altering the open reading frame of translation and generating a new sequence of amino acids in the final product (i.e., frameshift). Mutations also involve insertion or deletion of one or more nucleotides, which may lead to a shift in the open reading frame, or (when a multiple of three nucleotides are inserted or deleted) to the addition or removal of one or more amino acids in the final product, without affecting the reading frame.4 Experimental investigation of mutated K+ channels (or a normal channel with a mutated regulatory subunit) in heterologous expression systems such as Xenopus oocytes or mammalian cell lines has unequivocally demonstrated that LQTS-related mutations delay repolarization by reducing the outward K+ current through the affected channel (loss-of-function).3 It is important to note that loss-of-function effects of LQTS-related mutations in KCNQ1 and KCNH2 (causing LQT1 and LQT2, respectively) have also been shown in the much more native environment of cardiac myocytes derived from patient-specific pluripotent stem cells from members of families affected with these diseases.5,6 In general, mutations cause loss-of-function by decreasing the number of functional channels in the sarcolemma (lower expression) or by disrupting the extent or speed of channel opening and closing (altered gating). Because α-subunits of Kv channels assemble as tetramers to form functional ion channels, it is of functional importance whether mutated channel proteins possess the ability to assemble with normal channel proteins in heterozygous mutation carriers where both normal and mutated channels coexist (a normal allele is inherited from one parent and a mutant allele is inherited from the other parent). When mutated subunits assemble with normal subunits, they can disturb the sarcolemmal expression or gating of the normal channel subunits (i.e., a dominant-negative effect). In this case, the overall loss of K+ current will exceed 50%. In contrast, when mutant subunits do not participate in tetramer assembly, 50% reduction (maximally) in the K+ current is anticipated (i.e., haploinsufficiency). As expected, dominant-negative LQTS-linked mutations have a worse clinical outcome than mutations that cause haploinsufficiency.7,8 In addition, LQTS patients with compound mutations (≈8% of all genotyped patients) in the same gene, but particularly in different LQTS-related genes, are shown to display a more severe phenotype than single mutation carriers.9 These clinical data indicate that the extent of decrease in cardiac K+ currents may determine disease severity in LQTS. A delicate balance between inward and outward ion currents determines the repolarization of ventricular myocytes. Substantial differences in the expression levels of K+ channels between cardiac myocytes in different cardiac regions create a spatial dispersion of repolarization within the healthy ventricular myocardium. In LQTS, K+ current reduction leads to prolongation of the action potential plateau phase (reflected as QT interval prolongation on the ECG), and this allows recovery from inactivation and reactivation of L-type Ca2+ channels, which produces early afterdepolarizations (EADs). EADs, together with an accentuated spatial dispersion of repolarization, underlie the substrate and the trigger for the development of torsades de pointes in LQTS.10 The consensus is that EADs initiate torsades de pointes, and EADs are probably the initiating event in LQT2, the second most prevalent type of LQTS. However, in LQT1, the most common type of LQTS, where arrhythmic events usually and predictably start at higher heart rates, the arrhythmogenic mechanism might be different. Delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs), spontaneous action potentials during phase 4 of the cardiac action potential, might play a role in this condition. DADs may also trigger ventricular arrhythmias in LQT7 (see later). LQTS type 1 (LQT1), type 5 (LQT5), and type 11 (LQT11) are linked to mutations that cause a reduction in the slowly activating delayed rectifier K+ current (IKs) in the heart. The α-subunit of the channel responsible for IKs (Kv7.1) is encoded by KCNQ1, and Kv7.1 proteins require the presence of their regulatory β-subunit MinK (encoded by KCNE1) to conduct IKs. IKs is markedly enhanced by β-adrenergic stimulation through phosphorylation of Kv7.1 channels by protein kinase C (PKC), requiring MinK, and protein kinase A (PKA), requiring A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs). As a result, IKs enables the physiological response (i.e., abbreviation) of repolarization to fast heart rates during sympathetic nerve activity.11 In 1991, two linkage studies linked a gene locus on chromosome 11 to LQTS in several unrelated families. Five years later, positional cloning techniques established KCNQ1 as the chromosome 11–linked LQT1 gene.2 In 1997, targeted mutational analysis of KCNE1 in two families with LQTS identified two missense mutations in KCNE1 (LQT5).12 LQT1 is now known to account for nearly 40% of all LQTS cases. LQT5 is rare, and mutations in KCNE1 may be responsible for nearly 3% of all LQTS cases.13–15 In 2007, targeted mutational analysis of the translated exons of AKAP9, encoding the A kinase anchoring protein type 9 (AKAP9; also called Yatiao), identified a missense mutation in a single patient with LQTS (LQT11). So far, only this one mutation in Yatiao has been linked to LQTS.16 To date, more than 300 mutations in KCNQ1 have been linked to LQT1. Most mutations are missense mutations (≈70%), followed by frameshift mutations (≈10%), splice-site mutations (≈10%), nonsense mutations (≈5%), and in-frame deletions or insertions (≈5%).13–15 Novel mutation detection methods have demonstrated large genomic rearrangements (i.e., copy number variants) in KCNQ1, leading to the complete deletion of one or more exons in LQTS patients who were mutation negative after traditional point mutation analyses.17 This study suggests that the prevalence of copy number variants in LQT1 may be higher than was previously thought. LQT1 mutations in Kv7.1 are mostly located in the transmembrane segments (≈60%), the intracellular C-terminus (≈30%), and the intracellular N-terminus (≈10%).13–15 A fraction of these mutations have been investigated in experimental settings, and these studies have revealed an array of molecular mechanisms that underlie IKs loss-of-function (Figure 51-1) including (1) defective Kv7.1 protein synthesis, (2) defective trafficking of mutated Kv7.1 proteins to the sarcolemma and their retention in the endoplasmic reticulum, (3) impaired ability of mutated proteins to coassemble into tetrameric channels, (4) altered biophysical properties, (5) disrupted interaction with regulatory proteins, and (6) defective endosomal recycling.3,18–20 Of note, these mechanisms are not mutually exclusive. Loss-of-function alterations in biophysical properties of mutated IKs channels involve a slower rate of channel activation, a shift in the voltage dependence of activation toward more depolarized membrane potentials (indicating later channel activation), and accelerated deactivation (indicating faster channel closing). Disrupted interaction of mutated Kv7.1 proteins with the key regulatory protein AKAP9 has been demonstrated to reduce Kv7.1 phosphorylation by PKA upon β-adrenergic stimulation.19 Disrupted interaction with phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) results in reduced PKC-mediated phosphorylation of the Kv7.1 proteins. PIP2, a sarcolemmal lipid, increases IKs activity through phosphorylation.20 IKs is also increased by the stress hormone cortisol through the action of the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1 (SGK1). Cortisol upregulates SGK1, thereby facilitating endosomal recycling of Kv7.1 channels and stimulating their insertion into the sarcolemma. Mutations in Kv7.1 can disturb this process, causing further IKs reduction upon stimulation of SGK1 by cortisol.18 Figure 51-1 Common molecular mechanisms responsible for cardiac potassium channel loss-of-function or gain-of-function in inherited potassium channel diseases. Consistent with the molecular signaling pathways, LQT1-related cardiac events occur often during exercise (in particular swimming) and psychological stress, when the adrenergic tone and plasma levels of cortisol are increased.21 In addition, the QT interval fails to shorten appropriately, and might even lengthen (paradoxical QT response), in LQT1 patients upon an increase in heart rate (immediately at standing from supine position or at peak exercise, and during the recovery phase of treadmill exercise testing).22,23 In healthy subjects, QT intervals shorten at faster heart rates, enabling QTc to remain within normal limits with decreasing R-R intervals. Moreover, QTc duration lengthening is also observed in LQT1 patients in response to the intravenous infusion of epinephrine.24 These clinical features indicate loss of an adequate compensatory response of IKs to β-adrenergic stimulation and stress hormones, most probably as the result of reduced phosphorylation and disrupted endosomal recycling of mutated Kv7.1 channels. As expected, antiadrenergic therapies such as β-blockers and left stellate ganglion ablation have great efficacy in LQT1 patients.25,26 β-Blockers have been shown to diminish QTc changes during exercise or standing and significantly reduce the rate of cardiac events.22,25 Molecular genetics may be useful not only for diagnostic purposes, but also for risk stratification in LQT1. In a multicenter study in 600 LQT1 patients, significantly higher rates of cardiac events were found in patients with mutations located in transmembrane segments or with mutations that exert dominant-negative effects on normal IKs channel subunits.7 Another large multicenter study associated mutations in highly conserved amino acid residues in Kv7.1 with significant risk of cardiac events.27 Moreover, a recent study in 387 LQT1 patients correlated clinical phenotype with changes in biophysical properties of Kv7.1 channels caused by different KCNQ1 mutations. Especially, a slower rate of channel activation was associated with increased risk for events in LQT1.28 In all these studies, the effects of the mutations were independent of traditional risk factors (i.e., QTc, female gender, and β-blocker therapy). Mutation type and location may be used to predict whether a KCNQ1 mutation is pathogenic or is an innocuous rare variant.29 This is clinically relevant in that large overlap of QTc values has been noted between patients with LQTS and healthy patients. Non-missense mutations, regardless of location, have an estimated predictive value of more than 99% to be pathogenic, and missense mutations have a high predictive value when located in the transmembrane segments, the pore loop, and the C-terminus of Kv7.1 proteins.29 LQT1 patients with a mutation in the cytoplasmic loops are at higher risk for lethal arrhythmias than are patients with a mutation in other regions of Kv7.1, probably because of a pronounced reduction in channel activation upon β-adrenergic stimulation.30 Recent studies have identified single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the nitric oxide 1 adaptor protein gene (NOS1AP) as strong modulators of QT interval duration and risk of cardiac events in LQT1 (and other LQTS types).31,32 First, genome-wide association studies associated SNPs in NOS1AP with QT interval in the general population. Next, a role for NOS1AP SNPs was found in sudden cardiac death in the general population.33,34 In 2009, a family-based association analysis linked SNPs in NOS1AP with QT interval prolongation and risk for cardiac arrest and sudden death in a large South African cohort of LQT1 patients with the A341V mutation.31 NOS1AP encodes CAPON, an accessory protein of the neural nitric oxide synthase, which controls intracellular nitric oxide production. Functional studies indicate that CAPON fastens cardiac repolarization through inhibition of L-type Ca2+ channels.35 This provides a rationale for the association of SNPs in NOS1AP with QT interval duration. SNPs in the 3′-untranslated region (3′UTR) of KCNQ1 may also modulate phenotype severity in LQT. In a recent study in two independent LQT1 cohorts from the Netherlands and the United States, SNPs in KCNQ1‘s 3′UTR were associated with QTc duration and symptoms in an allele-specific manner. Patients with derived SNP variants on their mutated KCNQ1 allele had shorter QTc and fewer symptoms, while patients with these variants on their normal KCNQ1 allele had longer QTc and a greater number of symptoms. Experimental studies showed that the expression of KCNQ1‘s 3′UTR with derived SNP variants was less than the expression of 3′UTR with ancestral SNP variants. The 3′UTR play a crucial regulatory role in gene expression by controlling stability and translation of mRNAs. SNPs in this region were suggested to affect this function of the 3′UTR, thereby altering gene expression in an allele-specific manner.36 If true, this is expected to be especially relevant when one allele contains a pathogenic mutation. However, these findings await replication in larger LQT1 cohorts before their clinical use is proposed. The KCNE-encoded MinK exerts its regulatory effects on Kv7.1 via interactions between the transmembrane segments and the C-termini of the two proteins. In general, interactions between transmembrane segments are believed to be essential for normal channel activation, while interactions between the C-termini regulate channel assembly and channel deactivation. LQT5 mutations involve mainly missense mutations, although in-frame deletions, nonsense mutations, and frameshift mutations are also found.13–15 Most mutations impair the ability of MinK to modulate gating properties of Kv7.1, causing a shift in the voltage dependence of activation toward more depolarized potentials (in particular, mutations in the transmembrane segments) and accelerating deactivation.37 Other mechanisms include defective trafficking of mutated MinK proteins (and thereby Kv7.1 proteins), impaired channel assembly, and reduced sensitivity to PIP2.20,37 Residues in the C-terminus of MinK are identified as key determinants for sensitivity of Kv7.1 to PIP2, and LQT5-linked mutations in these residues are shown to reduce PIP2-mediated phosphorylation of Kv7.1 proteins by PKC.20 Because of its low prevalence, genotype-phenotype correlations in LQT5 are not available but may resemble those observed in LQT1. An SNP in KCNE2, D85N, located in the C-terminus of MinK, has been associated with QT interval duration in the general population,33,34 and is shown to be more prevalent in (genotype-negative) LQTS patients.38 Heterologous expression studies revealed significant loss-of-function effects of D85N on KCNQ1-encoded and KCNH2-encoded currents.38 Therefore, D85N is suggested to be a disease-causing variant in LQTS, and certainly a modifier of phenotype in LQT1 and LQT2 patients. AKAP9 (Yatiao) has an N-terminal and a C-terminal binding domain that interacts with the C-terminus of Kv7.1. The only LQT11 mutation described so far (S1570L) has been found in 1 out of 50 genotype-negative unrelated LQTS patients. S1570L is located in the C-terminal binding domain of AKAP9. It has been shown to disrupt, but not eliminate, the interaction between AKAP9 and Kv7.1, leading to reduced cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-mediated phosphorylation of Kv7.1 by PKA during β-adrenergic stimulation. This is speculated to result in less IKs enhancement during sympathetic nerve activity.16

Inheritable Potassium Channel Disease

Long QT Syndrome

IKs-Related Long QT Syndrome

Long QT Syndrome Type 1

Long QT Syndrome Type 5

Long QT Syndrome Type 11

Inheritable Potassium Channel Disease