Inflammatory Diseases of the Esophagus

Arvydas D. Vanagunas

Robert M. Craig

As pointed out by Baehr and McDonald,1 esophageal infections are predominantly due to diminished host defense, the use of antibiotics, or a structural abnormality of the esophagus, such as a stricture. Infections with herpes simplex virus (HSV) and Candida species occur rarely in the immunocompetent individual. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and immunosuppression for transplantation and treatment of malignant disease are responsible for the increased importance of benign inflammatory diseases of the esophagus. Common and uncommon opportunistic infections of the esophagus in immunocompromised patients are outlined in Table 148-1. The aggressive use of protease inhibitors to suppress the replication of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and the routine use of antiviral prophylaxis in transplant recipients has actually resulted in an overall reduction in opportunistic infections of the esophagus during the past several years. Esophagitis related to gastroesophageal reflux is discussed in Chapter 151, and irradiation damage to the esophagus is considered in Chapters 114 and 115.

Candida Esophagitis

With AIDS and immunosuppression for transplantation has come an increase in fungal and viral infections of the esophagus. The most common infection that occurs in patients with AIDS is Candida esophagitis; its presence establishes the diagnosis of AIDS in patients who have a positive serum HIV antibody. Candida esophagitis can also occur in patients who are not immunosuppressed, but there are usually predisposing factors, as pointed out by Fazio6 and Kodsi13 and their colleagues. Kodsi and associates13 noted that most esophagitis with normal immune status occurs in elderly patients. Other factors associated with the development of Candida esophagitis in immunocompetent patients include malnutrition, alcoholism, lymphoproliferative disease, cancer, and head and neck irradiation. The use of antibiotics as well as inhaled and systemic corticosteroids can also allow the development of Candida esophagitis. Usually, the infection resolves spontaneously with discontinuation of the antibiotic or corticosteroid. Rarely, diabetic patients develop Candida esophagitis spontaneously. Frick7 and Winston31 and their colleagues noted that whereas Candida esophagitis is quite common in patients with AIDS, it occurs less commonly in patients who undergo transplantation and immunosuppression, and the risk is less than 5% in transplant recipients given prophylactic antifungal therapy. Larner and Lendrum15 described a patient with esophageal candidiasis secondary to omeprazole use, presumably a result of diminished acid production in the stomach, which allows colonization in the stomach followed by esophageal infection.

Most immunocompetent patients with Candida esophagitis respond to the elimination of a predisposing antibiotic or corticosteroid. Agents such as clotrimazole and nystatin mouthwash are effective for oral candidiasis and as prophylaxis against esophageal infection but are generally less effective than oral azoles. Azoles (ketoconazole, fluconazole, and itraconazole) are the agents of first choice in treating Candida esophagitis, and Barbaro and colleagues2 demonstrated in a randomized controlled trial that fluconazole, 100 to 200 mg daily, is the superior agent in patients with AIDS. Ketoconazole is generally less effective than the other azoles, and Laine and colleagues14 have suggested that the inefficacy of ketoconazole may be attributed to the necessity of an acid pH in the stomach for optimal ketoconazole absorption and to the increased frequency of hypochlorhydria in patients with AIDS.

Often, the esophagitis is so severe that the entire esophagus is filled with a pseudomembranous exudative infiltrate. The infection can invade the esophageal wall and produce systemic candidiasis. The patient should receive intravenous amphotericin B if there is not a rapid response to fluconazole. In general, the use of amphotericin B requires hospitalization. Once the patient has been shown to tolerate the medication well, he or she can be discharged to receive intermittent therapy intravenously at home. Amphotericin B is an effective agent but its severe side-effect profile, including renal toxicity, is problematic. A low dose of intravenous amphotericin B (10 to 20 mg daily) for a total dose in the range of 100 to 200 mg may be effective in curing Candida esophagitis. Lipid-based formulations of amphotericin B are currently available; these decrease the nephrotoxicity risk without compromising antifungal effects. Villanueva and colleagues26 described the effectiveness of a new echinocandin drug, caspofungin, as a less toxic alternative to amphotericin B in azole-resistant patients. This drug was approved in 2001 under the name Cancidas for patients who do not tolerate amphotericin B antifungal therapy.

Table 148-1 Opportunistic Pathogens of the Esophagus in Immunocompromised Patients | |

|---|---|

|

Diagnosis

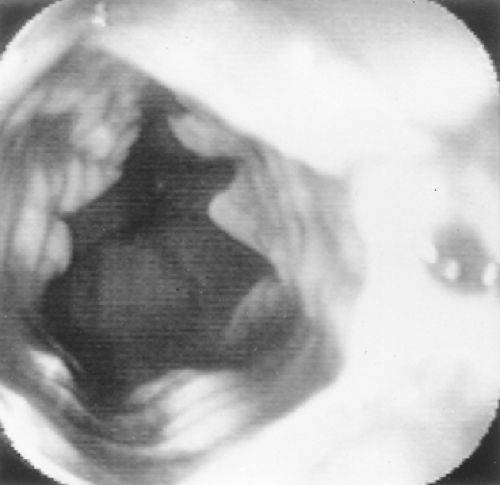

Oral candidiasis (thrush) may be seen with candidal esophagitis, but its absence does not exclude infection of the esophagus. The diagnosis of candidal esophagitis is established by upper endoscopy with cytologic and tissue analysis (Fig. 148-1). Endoscopy is the diagnostic procedure of choice, although antifungal empiric therapy when thrush is present is an acceptable approach. Endoscopy should be considered if symptoms do not resolve rapidly. The endoscopic appearance may range from a few white plaques to a confluent, thick, yellowish exudate coating the mucosa and encroaching on the esophageal lumen (Fig. 148-2). Brandt and colleagues3 described a technique involving the blind passage of a cytology brush transnasally. This technique is quite sensitive for the diagnosis of Candida but less reliable for HSV or cytomegalovirus (CMV) esophagitis. Patients with infectious esophagitis usually have odynophagia and often also dysphagia. Usually, esophageal candidiasis remains localized in the esophagus without systemic dissemination.

Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis is a rare illness affecting the patient’s T cells. The mouth, larynx, skin, and nails are usually involved with the infection. Often, esophagitis ensues as part of the generalized process.

Radiographic Features

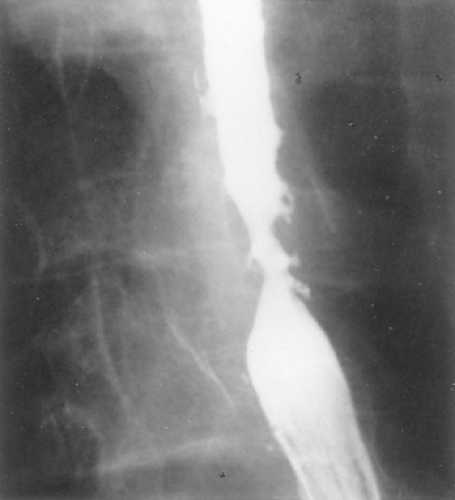

Patients with candidal esophagitis have large intramural defects owing to the pseudomembranous process. In addition, intramural pseudodiverticulosis sometimes is evident (Fig 148-2). Glick10 points out that candidal esophagitis can mimic viral esophagitis radiographically, thus necessitating endoscopic clarification.

Other Fungal Diseases

Rarely, other fungal diseases can affect the esophagus, especially in patients with AIDS. Fungi typically spread to the esophagus by contiguous spread from lymph nodes in the mediastinum or by vascular dissemination, although primary esophageal infection can occur. The presentations mimic other opportunistic esophageal infections, with odynophagia as the primary symptom. Long fibrosing esophageal strictures or fistulas should raise clinical suspicion of an atypical fungal infection. Torulopsis glabrata esophagitis was described by Mukherjee.20 Fortunately, because it is quite resistant to therapy, this is a rare complication in AIDS. An unusual finding of actinomycosis of the esophagus with resulting esophagobronchial fistula was reported by Vinson and Sutherland27 in an immune-depressed patient.

Aspergillosis, blastomycosis, mucormycosis, and histoplasmosis infections of the esophagus have been described.

Aspergillosis, blastomycosis, mucormycosis, and histoplasmosis infections of the esophagus have been described.