Infections of the Chest Wall

Joseph LoCicero III

Chest wall infections can be categorized either as primary problems arising spontaneously or as secondary problems caused by previous procedures or preexisting disease states. The result is the same, with equally devastating potential complications. Management of such infections may be as simple as administering routine antibiotic therapy or may require multiple and prolonged drainage procedures and complex reconstructive operations. Prompt intervention is essential to minimize serious morbidity.

Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

The thorax accounts for one-fifth of the total body surface area and thus can be afflicted with many common, nonspecific soft tissue infections. Furuncles and boils common to any hair-bearing surface frequently occur. Superficial infections often develop in minor injuries and burns of the chest, as they do elsewhere in the body.

Abscesses

Soft tissue abscesses may occur anywhere on the chest wall. They are characterized by the usual signs and symptoms of an abscess anywhere on the body and are rarely associated with an abnormal chest radiograph. Two potentially serious infections specific to the chest wall and involving large potential spaces are subpectoral and subscapular abscesses. These occasionally present as primary infections but more often are secondary to a chronically infected thoracotomy incision. They are characterized by local pain, with or without swelling, combined with fever and leukocytosis. Computed tomography (CT) easily identifies and localizes the problem. Prompt drainage and appropriate antibiotic therapy usually lead to successful resolution. Suction catheters are rarely required because these spaces are obliterated once drained. Occasionally, when the abscess is large, several counterincisions are made to debride and pack the space more completely.

Tubercular Abscesses

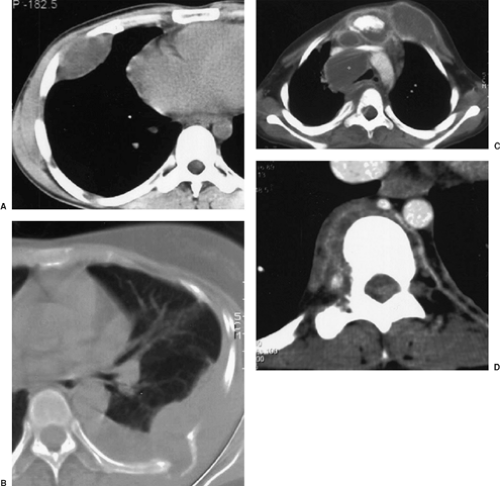

With the worldwide increase in tuberculosis and immigration of people from the third world to North America, pulmonary tuberculosis may be seen in any thoracic surgical practice. Like tuberculous infections of the skin on the neck, called scrofula, mycobacteria can cause a soft tissue infection of the chest wall. Hsu and colleagues24 reviewed its management in 1995. Even bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) spread from immunization has caused chest wall infection, as documented by Bellet and Prose.5 Patients present with a slowly enlarging, sometimes painful, sometimes painless mass on the chest wall. A CT scan is helpful to determine the extent of involvement. Figure 45-1 demonstrates that the surface involvement may be the simplest part of the abscess. Diagnosis can be made with a diagnostic aspiration of the abscess. Treatment should begin preoperatively with combination antituberculous therapy and continue for 6 to 9 months. Although Hsu24 advocated that surgical debridement should be reserved for failures, Kim and colleagues25 showed in 2008 that they could lower the recurrence rate of abscesses from 40% to 9.2%. Also, Cho and associates10 showed that the use of adequate preoperative antibiotic therapy markedly decreased the need for a second surgical debridement.

Fungal infections of the chest wall should also receive long-term antibiotic therapy, but radical debridement is a mandatory part of the therapy.

Gangrene

Necrotizing soft tissue infections may occur as a complication of empyema or trauma. These infections frequently begin when the pleural material is drained through the soft tissues either by chest tube or thoracotomy. Pingleton and Jeter37 reported extensive synergistic gangrene of the chest wall with Bacteroides melaninogenicus and Streptococcus viridans after tube thoracostomy for empyema. Delay in recognition led to the patient’s demise. The present author and Vanecko26 reported destruction of the pectoralis major and serratus muscles caused by clostridial myonecrosis at the site of a tube thoracostomy in a patient with Boerhaave’s syndrome. Radical debridement and daily dressing changes under general anesthesia eventually led to a successful outcome. Viste and colleagues48 reported a case of necrotizing infection caused by gastric herniation after laparoscopic fundoplication. Urschel and associates47 reviewed the world literature and found a 90% mortality rate for this devastating problem. A more recent review by Losanoff and colleagues27 found that the mortality rate for adults remained high at 73%.

Infections of the head and neck as well as dental manipulation have been identified as sources of necrotizing fasciitis of the chest. Steel41 described a case of necrotizing ulceration of the chest wall after dental manipulation; it was successfully

treated by surgical debridement and chemotherapy. He noted that the primary suspect organisms were Streptococcus milleri and Bacteroides species. Nallathambi and colleagues33 reviewed the current literature and discovered 28 chest wall and mediastinal infections related to dental manipulation or pharyngeal abscesses. These rapidly progressive, mixed aerobic and anaerobic infections have been associated with a 32% mortality rate. Antibiotic prophylaxis for deep dental manipulations and careful follow-up for any early signs of sepsis are essential.

treated by surgical debridement and chemotherapy. He noted that the primary suspect organisms were Streptococcus milleri and Bacteroides species. Nallathambi and colleagues33 reviewed the current literature and discovered 28 chest wall and mediastinal infections related to dental manipulation or pharyngeal abscesses. These rapidly progressive, mixed aerobic and anaerobic infections have been associated with a 32% mortality rate. Antibiotic prophylaxis for deep dental manipulations and careful follow-up for any early signs of sepsis are essential.

Early recognition, radical debridement of all involved necrotic tissue, high-dose antibiotic therapy, prolonged ventilatory support, and delayed closure with biologic tissue represent the only salvation for these patients. The antibiotic of choice used to be single-drug treatment with high-dose penicillin, but many organisms of the normal flora above the diaphragm have become resistant to penicillin. Therapy should begin presumptively with a combination that includes penicillin or ampicillin, an aminoglycoside, and clindamycin or metronidazole. Once cultures and susceptibilities are available, the antibiotic regimen should be tailored accordingly. Additional therapeutic modalities yet to be studied in trials are hyperbaric oxygen therapy and wound VAC (KCL, San Antonio, TX) dressings following control of local sepsis.

Infectious Chest Wall Invasion

With drug resistance and superinfection during antibiotic therapy, virulent organisms occasionally cause pneumonia, which

has the capability of direct chest wall invasion. Suchyta and associates42 reported a community-acquired chronic Acinetobacter calcoaceticus pneumonia with direct chest wall involvement discovered only at autopsy. In 1992, Yuan and associates52 successfully treated a patient with pneumonia and extensive chest wall involvement attributed to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. This patient required high-dose penicillin therapy for 3 months. However, as Hseih and colleagues20 point out, Actinomyces species (i.e., israelii, naeslundii, and odontolyticus) infections usually respond to antibiotic (penicillin) therapy, and surgical intervention may not be necessary if pretherapeutic diagnosis can be made.

has the capability of direct chest wall invasion. Suchyta and associates42 reported a community-acquired chronic Acinetobacter calcoaceticus pneumonia with direct chest wall involvement discovered only at autopsy. In 1992, Yuan and associates52 successfully treated a patient with pneumonia and extensive chest wall involvement attributed to Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. This patient required high-dose penicillin therapy for 3 months. However, as Hseih and colleagues20 point out, Actinomyces species (i.e., israelii, naeslundii, and odontolyticus) infections usually respond to antibiotic (penicillin) therapy, and surgical intervention may not be necessary if pretherapeutic diagnosis can be made.

Empyema Necessitatis

Infrequently seen today, the soft tissue infection called empyema necessitatis (or necessitans) is caused by an undrained underlying pleural infection. An untreated empyema may eventually burrow through the chest wall and into the subcutaneous tissue of the chest. Suspicion of this entity should be raised by the patient’s history and confirmed by physical and radiographic examination of the chest. The soft tissue component may require separate drainage but often resolves with appropriate drainage of the empyema. If spontaneous drainage of the empyema necessitatis occurs, it is rarely adequate unless the underlying component is managed also.

Miscellaneous Infections

Several other conditions may manifest as infections of the chest wall. Golladay and associates14 noted three benign conditions in 24 children who presented with chest wall masses. These included trichinosis, nodular fasciitis, and myositis ossificans, all confirmed by excisional biopsy. The latter two were almost certainly secondary to localized trauma.

Mondor’s Disease

Mondor’s disease is a benign condition consisting of localized thrombophlebitis occurring in the superficial veins of the breast and anterior chest wall. The true incidence of this entity is unknown. Reports have been sporadic. Because the condition produces few symptoms and signs, most examples are probably not referred to informed examiners for study.

The earliest description was by Fagge13 in 1869. Williams51 attributed the disease to thrombophlebitis, as did Mondor in 1939,30 for whom the condition is named. Most cases occur in women, and frequently no antecedent cause can be found. Radical mastectomy may predispose to the development of this disease, whereas benign conditions, such as fibrocystic disease, have no association with this entity. In a few instances in which a biopsy was performed, microscopy demonstrates a sclerosing endophlebitis with complete or partial obliteration of the lumen. In 2008, Ichinose and associates22 demonstrated conclusively through immunohistochemistry that the vast majority of cases are due to thrombophlebitis. Several case reports suggest that the etiology may be a hypercoagulable state, so protein S disease should be ruled out.

Clinically, the disease presents as a cordlike structure in the subcutaneous tissue of the axilla, chest, or abdomen. Its greatest significance may be the possible confusion with inflammatory carcinoma of the breast. It does not tend to recur or lead to thromboembolism. In most subjects, no specific therapy is indicated because the lesion regresses spontaneously.

Cartilage and Bony Structures

Tietze’s Syndrome

Painful, nonsuppurative swelling of the costal cartilages without abnormal histologic change is referred to as Tietze’s syndrome, or chondrodynia. This condition, which is not a disease, was described in two patients by Tietze,45 who attributed the changes to tuberculosis. This has never been confirmed. Since Tietze’s publication, case reports have been sporadic. Kayser,24 who reviewed the world literature, could find only 156 cases. The true frequency of this condition is not known, but the symptom complex appears to be common. Peyton36 described 76 women in his office practice and 156 men and women visiting an emergency room who complained of this syndrome.

Symptoms include chest pain and swelling of the costochondral junction. The junction, usually the second, is usually prominent and is tender to deep palpation. Peyton noted that emotional tension is frequently associated with this symptom complex. In a study by Disla and colleagues,11 of 122 consecutive patients with chest wall complaints presenting to the emergency room, 30% met criteria for diagnosis of costochondritis and 8% met the American College of Rheumatology criteria for fibromyalgia. After 1 year, 55% of the patients with costochondritis still had symptoms. Edelstein and colleagues12 pointed out that CT scan of the chest is helpful to exclude chest wall masses in these patients.

As might be expected for a condition as vague as this, several invasive treatments have been advocated, from hydrocortisone infiltration to surgical removal of the involved area. The latter hardly seems justified. In most patients, reassurance and symptomatic treatment with compounds containing ibuprofen are sufficient.