8

CHAPTER

![]()

Infections II: Granulomatous Infections

This chapter includes selected infections likely to be encountered on biopsy or surgical specimens in which granulomatous inflammation, usually necrotizing or a combination of necrotizing and non-necrotizing, is the primary tissue reaction. The emphasis is on histologic characteristics that aid in correctly identifying the responsible organisms.

TOPICS

Evaluation of Necrotizing Granulomas

Evaluation of Necrotizing Granulomas

Histoplasmosis

Histoplasmosis

Cryptococcosis

Cryptococcosis

Coccidioidomycosis

Coccidioidomycosis

Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis

Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections

Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections

Dirofilarial Nodule (Dog Heartworm Disease)

Dirofilarial Nodule (Dog Heartworm Disease)

EVALUATION OF NECROTIZING GRANULOMAS

The vast majority of necrotizing granulomas are infectious in etiology. Although cultures remain the gold standard for diagnosis of most infections, they are not always taken, and the results may not be known for several weeks. Noninfectious necrotizing granulomatous disorders (see Chapter 6) are quite rare, but they often have a fulminant course requiring prompt treatment, and infection may have to be excluded histologically before culture results are available. Pathologists, therefore, need to be able to efficiently search for organisms, and when found, accurately identify them. This process requires synthesis of the hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) appearance and the results of special stains, and it does not have to be tedious.

We recommend using Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) stain for fungi and Ziehl–Neelsen or auramine–rhodamine stains for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) following a careful examination of the slides in H and E. The slides can be scanned at intermediate magnification (10x to 20x) for most organisms. High magnification (40x) should be used to search for histoplasma and to identify AFB. Oil (100x) should be used only to ascertain that positive staining is “real” and not an artifact. This particularly pertains to AFB, as random AFB positive artifacts are common. Slides should not be screened under oil, however.

Table 8.1 lists the steps useful for identifying organisms in necrotizing granulomas. First, the H and E stain should be examined at low magnification to assess the overall features of the granulomatous process, and then higher magnification can be used to search for and to identify fungal organisms. Although there are no granulomatous features entirely specific to a particular organism, some features favor certain organisms. For example, suppuration is more common in blastomycosis and coccidioidomycosis, whereas amorphous necrosis is seen more often in histoplasmosis and tuberculosis, and non-necrotizing granulomas are more common in cryptococcosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial infections.

Many fungi are visible in H and E, both within the necrotic zones and within histiocytes, and their morphologic features should be assessed at high magnification. GMS is used to confirm that the structures seen on H and E are fungi or to find them when they are not visible in H and E. The combination of the tissue reaction and the morphology of the fungus in both H and E and GMS stains usually leads to accurate identification. The main differentiating features of the common fungi causing granulomatous inflammation are summarized in Table 8.2.

TABLE 8.1 Evaluation of Necrotizing Lung Granulomas

I. | At low magnification evaluate features of granulomatous inflammation in H and E:

|

II. | At high magnification look for fungi in H and E:

|

III. | Evaluate special stains:

|

IV. | Use the H and E findings along with the results of special stains to identify the organism |

AFB, acid-fast bacilli; GMS, Gomori methenamine silver; H and E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Acid-fast stains should be searched after fungal stains are negative, and the pathologist should focus the search on the most necrotic areas of the granulomas rather than looking in areas of viable parenchyma. Similarly, in histoplasma granulomas, the organisms cannot be seen in H and E and are usually found only in the central-most necrotic areas of granulomas. Therefore, pathologists need not waste time searching other areas. Up to three blocks containing necrotic areas should be examined with special stains, but stains are rarely productive in additional blocks or if necrotic areas are not present in the blocks.

Helpful Tips—Granulomatous Infections

Save time by beginning your organism search in the central, most necrotic portions of granulomatous inflammation.

Save time by beginning your organism search in the central, most necrotic portions of granulomatous inflammation.

Perform special stains in up to three blocks, and choose ones containing the most active, necrotic granulomatous inflammation.

Perform special stains in up to three blocks, and choose ones containing the most active, necrotic granulomatous inflammation.

Use morphologic features of the organism in both H and E and GMS combined with the appearance of the tissue reaction to help identify fungi.

Use morphologic features of the organism in both H and E and GMS combined with the appearance of the tissue reaction to help identify fungi.

HISTOPLASMOSIS

Histoplasmosis is endemic in the central United States, although cases occur well beyond this area. The disease is usually self-limited, and most patients are asymptomatic. Pathologists most often encounter this infection in a nodule biopsied because of the radiographic suspicion of tumor, although rare cases of acute, symptomatic disease may occasionally also undergo biopsy.

Histologic Features

Necrotizing granulomatous inflammation (except in disseminated histoplasmosis; see the following section, “Disseminated Histoplasmosis”)

Necrotizing granulomatous inflammation (except in disseminated histoplasmosis; see the following section, “Disseminated Histoplasmosis”)

Oval-shaped yeasts, small and uniform in size, not visible in H and E (except when intracellular in disseminated histoplasmosis only)

Oval-shaped yeasts, small and uniform in size, not visible in H and E (except when intracellular in disseminated histoplasmosis only)

Typically, necrotizing granulomatous inflammation is seen in all clinical forms (see the subsequent section, “Clinical Features”) of histoplasmosis except for disseminated histoplasmosis. The granulomatous inflammation often appears nearly quiescent with well-circumscribed necrotic areas bounded by a thin rim of epithelioid histiocytes admixed with abundant collagen and chronic inflammation (Figure 8.1). Other cases may appear more active with infarct-like areas and abundant cellular debris within the central necrosis surrounded by a thick rim of plump epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells (Figure 8.2). In early active cases, the necrotic zones are not well circumscribed and may have irregular contours with a haphazard “geographic” pattern (Figure 8.3). Vascular inflammation commonly accompanies the other changes and may be granulomatous (Figure 8.2C; see also Figure 6.15). A necrotizing vasculitis (see Chapter 6) is not a feature, however.

Histoplasma yeasts are best outlined with a GMS stain, and they are found in the central-most necrotic areas of the granulomas (Figures 8.1 and 8.3). A Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain only weakly, if at all, stains the organisms, however, and should not be used to screen for fungi in necrotizing granulomas. The organisms are small, about half the size of a red blood cell, uniform in size, and oval shaped. Because they are so small, they can be easily overlooked or mistaken for anthracotic pigment in GMS stains if the slides are scanned at low magnification (Figure 8.3B).

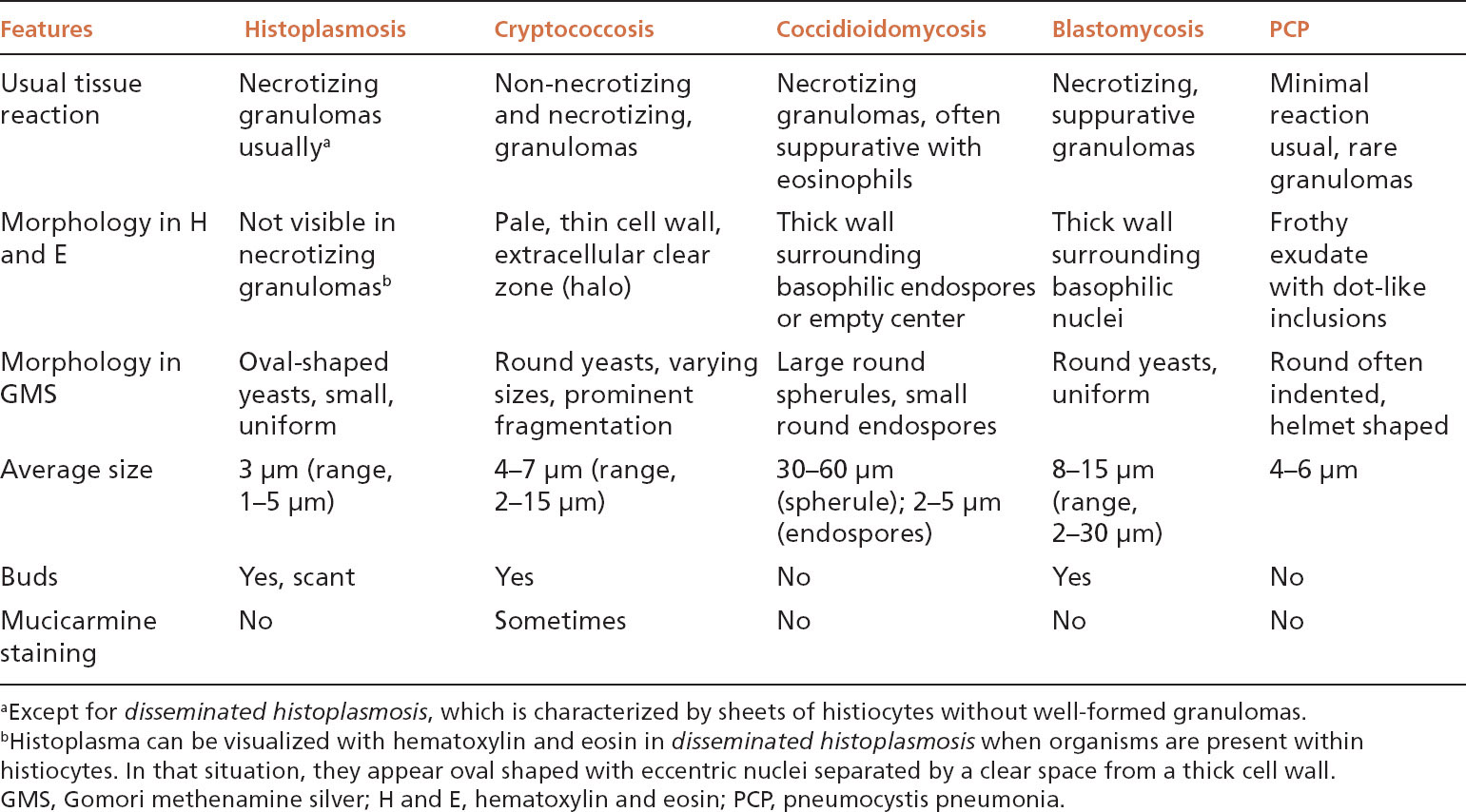

TABLE 8.2 Contrasting Features of Granulomatous Fungal Infections

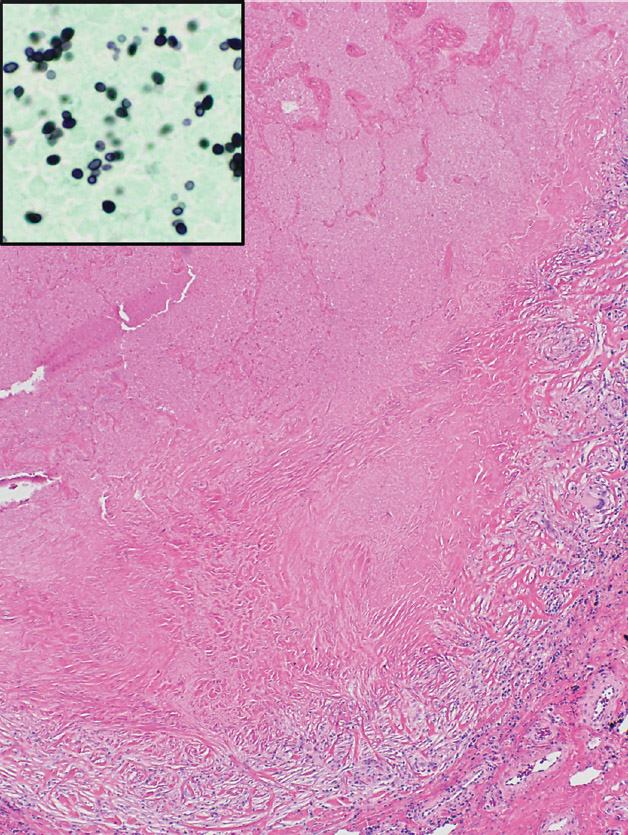

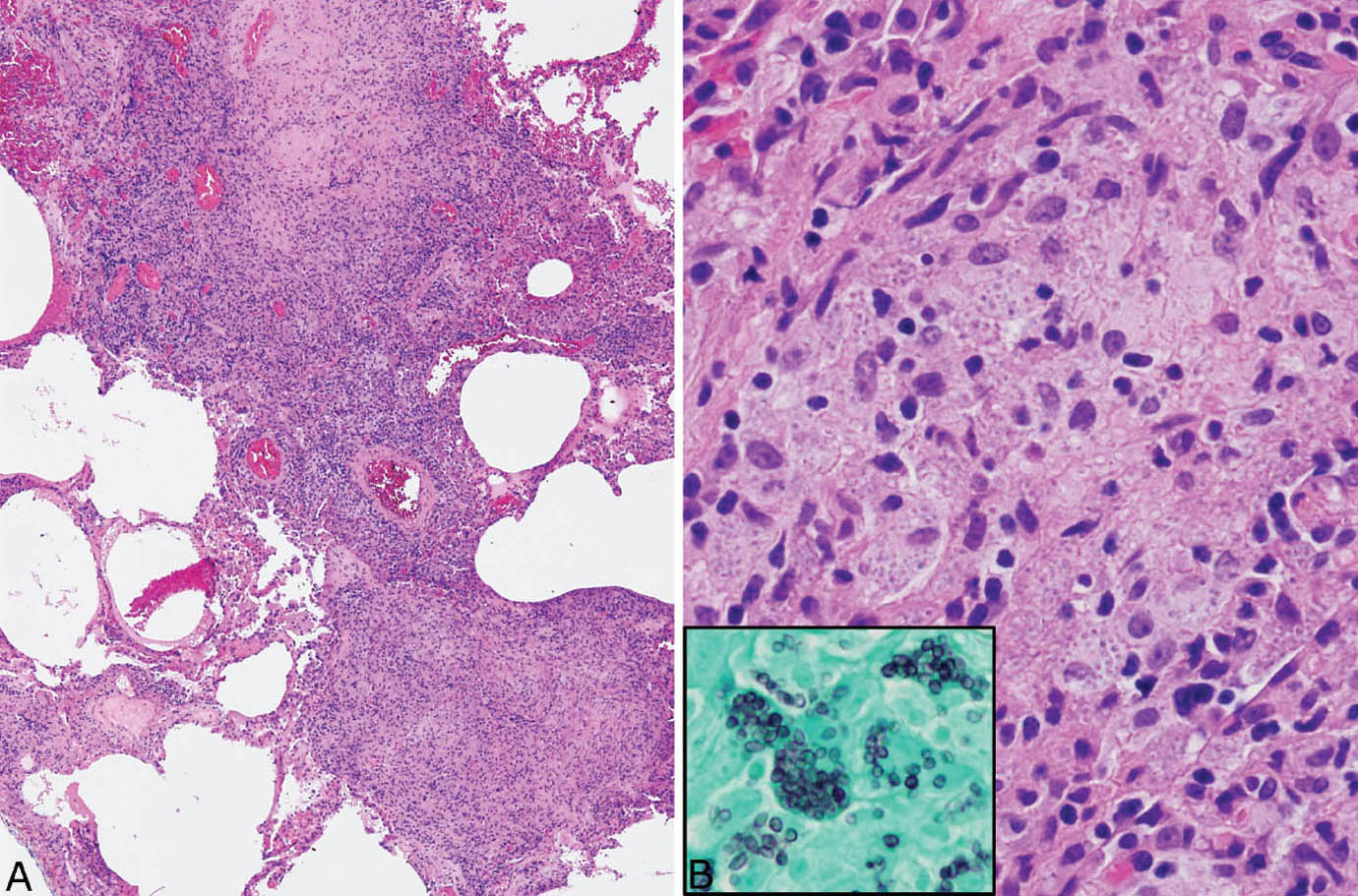

FIGURE 8.1 Histoplasmosis. This example is a typical nodule (histoplasmoma) with rounded borders and prominent central necrosis surrounded by a thin rim of epithelioid histiocytes and collagen. The process appears fairly quiescent. The inset is a GMS stain showing the characteristic small, uniform, oval-shaped yeasts present in the center of the necrotic zone. GMS, Gomori methenamine silver.

Disseminated Histoplasmosis

Disseminated histoplasmosis differs from other forms of histoplasmosis in that well-formed granulomatous inflammation is typically absent. Rather, sheets of histiocytes admixed with variable chronic inflammation are present mainly within the interstitium and they may replace portions of parenchyma (Figure 8.4). Focal necrosis is occasionally present, but organized necrotizing granulomatous inflammation is not seen. The organisms are present within the histiocyte cytoplasm and also spill into alveolar spaces where they can be found within the cytoplasm of alveolar macrophages. The intracellular organisms (in contrast to free organisms in necrotic granulomas) are easily visible in H and E stains, in which they produce a characteristic coarsely granular appearance at low magnification (Figure 8.5). Their morphology is better appreciated at high magnification where they appear as small, oval-shaped structures containing basophilic, eccentrically placed, dot-like, or crescent-shaped nuclei separated by a clear space from a lightly staining cell wall. The appearance is similar to that of leishmaniasis, but positive GMS staining excludes that diagnosis.

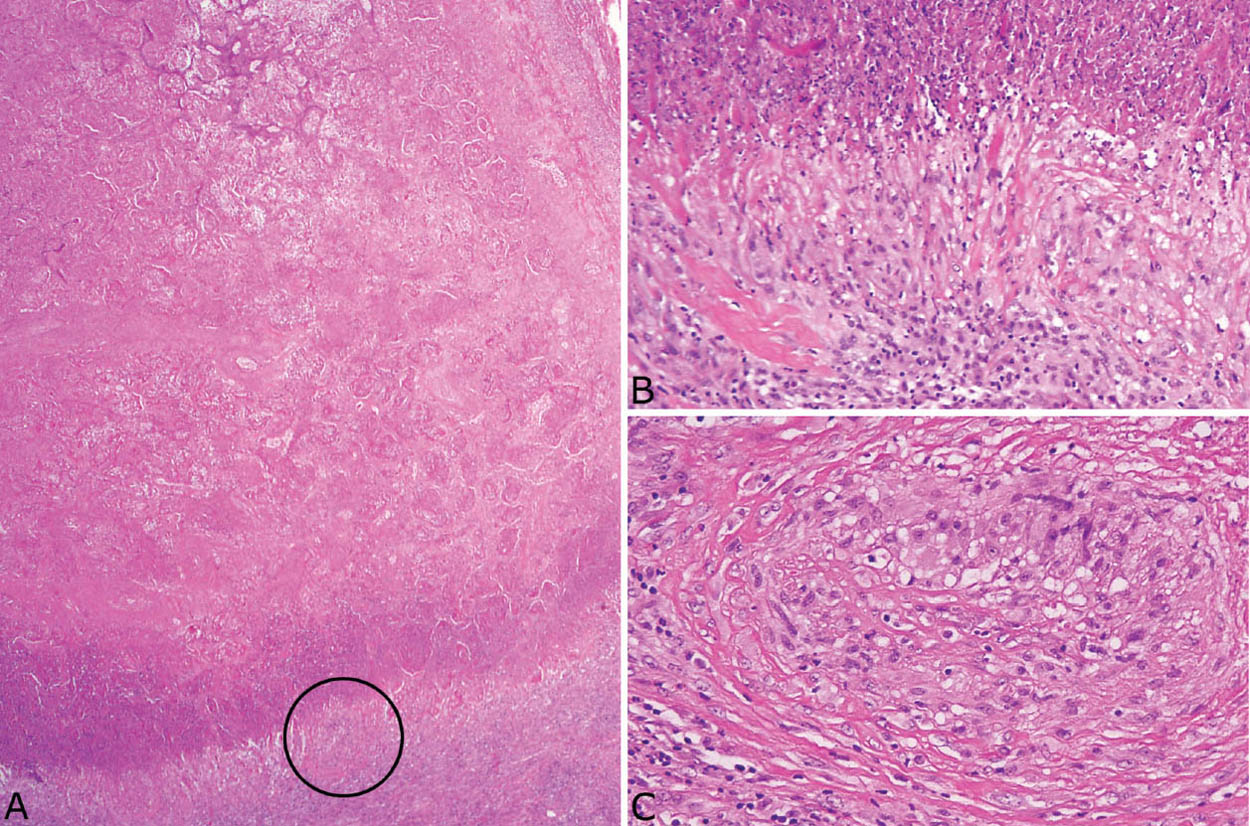

FIGURE 8.2 Histoplasmosis. (A) The necrotizing granulomatous inflammation in this histoplasmoma appears more active with prominent infarct-like necrosis and a basophilic “dirty” appearance at the edge. (B) Higher magnification from the edge shows abundant nuclear debris causing the “dirty” appearance to the necrosis with a surrounding rim of plump epithelioid histiocytes. (C) A granulomatous vasculitis is present adjacent to the necrotic zone (circled area in [A]). Note that although the blood vessel wall is almost completely replaced by the granulomatous inflammation, there is no associated necrosis.

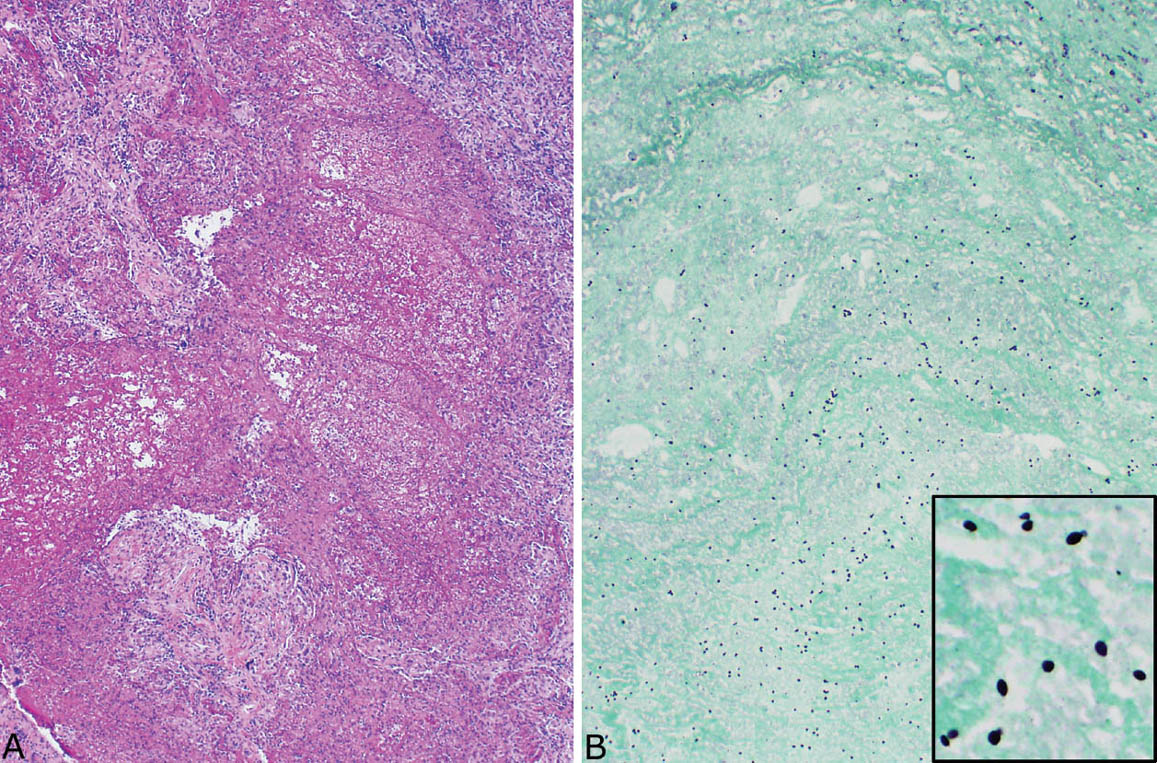

FIGURE 8.3 Histoplasmosis. (A) The necrotizing granulomatous inflammation in this case of acute histoplasmosis appears quite active with irregular, “geographic” necrotic zones containing remnants of lung parenchyma and nuclear debris. (B) A GMS stain at low magnification shows numerous organisms that can be mistaken for anthracotic pigment at this magnification. The inset is a high magnification showing the typical oval-shaped yeasts, one of which is budding (upper right). GMS, Gomori methenamine silver.

FIGURE 8.4 Disseminated histoplasmosis. (A) At low magnification, the interstitium is thickened and distorted by a histiocytic and chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. (B) A higher magnification shows histiocytes with coarsely granular cytoplasm that is caused by myriads of intracellular yeasts, which are confirmed by a GMS stain (inset). Well-formed granulomatous inflammation is not present. GMS, Gomori methenamine silver.

FIGURE 8.5 Disseminated histoplasmosis. (A) In this example, the organisms are present within alveolar macrophages and interstitial histiocytes. Note the granular appearance to the cytoplasm. (B) At high magnification, the eccentric dot-like nuclei of histoplasma with surrounding clear space are better appreciated. The inset is a GMS stain from the same area. GMS, Gomori methenamine silver.

Differential Diagnosis

The organisms most often considered in the differential diagnosis of histoplasma in necrotizing granulomas include cryptococcus and occasionally pneumocystis. Although histoplasma is considerably smaller than cryptococcus and pneumocystis, assessment of size is difficult and at best subjective in a given case. Probably, the most helpful features of histoplasma are the oval shape, the uniformity in size, and the fact that they are not visible in H and E stains in necrotic granulomas. Their contrasting features are summarized in Table 8.3.

Clinical Features

There are several clinical forms of histoplasmosis. Solitary necrotizing granulomas, so-called histoplasmomas, are common and most likely to be encountered by pathologists. They are usually incidental findings on chest radiographs and are biopsied or excised because of the radiographic suspicion of malignancy. Acute histoplasmosis is more common than histoplasmomas, but only rarely comes to biopsy as most patients are asymptomatic or have self-limited mild symptoms. Chronic histoplasmosis is uncommon. It occurs in patients with underlying chronic lung disease and may mimic tuberculosis with upper lobe, often cavitary, lung infiltrates. The diagnosis is made from sputum cultures and serologic test results in most cases with biopsy only rarely undertaken. Disseminated histoplasmosis occurs almost exclusively in immunocompromised persons or in infants. It is characterized by widespread parasitization of macrophages by the organisms with multiple organs, especially reticuloendothelial, involved. The diagnosis is usually made from blood or urine cultures or from biopsy of extrapulmonary sites, especially bone marrow or liver. Lung biopsy may be performed is cases in which pulmonary manifestations are prominent clinically.

Helpful Tips—Histoplasmosis

Histoplasma are small and easily overlooked at low magnification in GMS stains; use at least 20x magnification in searching for the organism.

Histoplasma are small and easily overlooked at low magnification in GMS stains; use at least 20x magnification in searching for the organism.

Do not use PAS to look for histoplasma in necrotizing granulomas, as the organisms within the necrotic areas are usually not visible in this stain (although it will outline them within cells in disseminated disease).

Do not use PAS to look for histoplasma in necrotizing granulomas, as the organisms within the necrotic areas are usually not visible in this stain (although it will outline them within cells in disseminated disease).

CRYPTOCOCCOSIS

Cryptococcus is a ubiquitous yeast whose natural habitat is soil, especially that contaminated with pigeon droppings. It may infect both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals, and is most often encountered by pathologists in biopsies or excisions of localized nodules or infiltrates.

Histologic Features

Non-necrotizing and necrotizing granulomatous inflammation

Non-necrotizing and necrotizing granulomatous inflammation

Round, budding yeasts varying in size and often fragmented, usually surrounded by a clear zone, and visible in H and E stains

Round, budding yeasts varying in size and often fragmented, usually surrounded by a clear zone, and visible in H and E stains

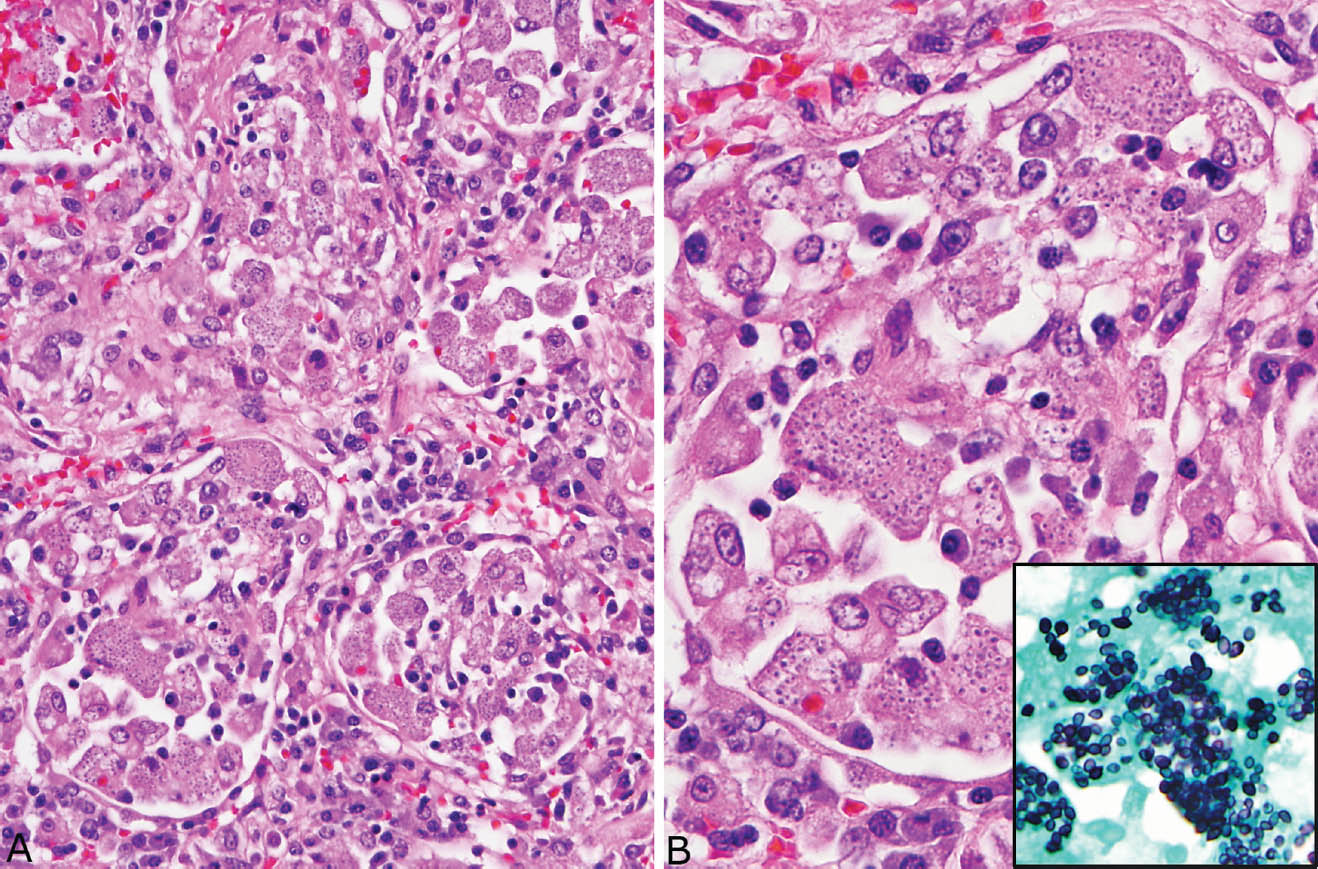

A wide spectrum of inflammatory changes can be encountered in pulmonary cryptococcosis that depends partly on the patient’s immune status. Loose, non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation is the most common finding (Figure 8.6). It is characterized by poorly organized aggregates of epithelioid histiocytes, often large and multinucleated, within background fibrosis and chronic inflammation. A bubbly appearance of the histiocyte cytoplasm because of clusters of intracellular organisms is frequently seen at low magnification (Figure 8.6A). Organizing pneumonia usually accompanies the histiocyte infiltrate and may be prominent (Figure 8.7A). Extracellular yeasts can also be seen within background inflammation and fibrosis, where they frequently occur in small clusters within larger clear spaces (Figures 8.7B and 8.7C).

TABLE 8.3 Distinction of Histoplasma, Cryptococcus, and Pneumocystis in Necrotizing Granulomas

Histoplasma | Cryptococcus | Pneumocystis |

Not visible in H and Ea | Characteristic yeasts with surrounding clear halo in H and E | Frothy exudate in H and E |

Not intracellulara | Intracellular yeasts common | Not intracellular |

Oval shape, uniform, small size in GMS | Round, varying sized with fragmentation in GMS | Round, uniform, occasional helmet forms in GMS |

Rare buds | Frequent buds | No buds |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree