7

CHAPTER

![]()

Infections I: Nongranulomatous Pneumonias

This chapter includes nongranulomatous pneumonias in which a microbe can usually be identified in biopsy specimens, and in which pathologic recognition may be necessary for diagnosis before the results of cultures and other laboratory studies are available. Common bacterial pneumonias that are usually diagnosed clinically are not included.

TOPICS

Viral

Viral

Cytomegalovirus Pneumonia

Cytomegalovirus Pneumonia

Herpes Simplex/Varicella-Zoster Pneumonia

Herpes Simplex/Varicella-Zoster Pneumonia

Adenovirus Pneumonia

Adenovirus Pneumonia

Measles Pneumonia

Measles Pneumonia

Influenza and Other Viral Pneumonias

Influenza and Other Viral Pneumonias

Fungal

Fungal

Invasive Aspergillosis/Mucormycosis

Invasive Aspergillosis/Mucormycosis

Candida Pneumonia

Candida Pneumonia

Mycetomas

Mycetomas

Pneumocystis Pneumonia

Pneumocystis Pneumonia

Bacterial

Bacterial

Nocardiosis

Nocardiosis

Actinomycosis

Actinomycosis

Legionnaires’ Disease

Legionnaires’ Disease

Rhodococcus Equi Pneumonia/Malakoplakia

Rhodococcus Equi Pneumonia/Malakoplakia

VIRAL PNEUMONIA

Viral pneumonia is common, and there are a large number of potential respiratory viral pathogens. Most cases are mild and self-limited, however, and only rare cases come to biopsy. This section focuses on selected severe viral pneumonias that may undergo biopsy.

Many viruses can be accurately identified in routine stains by considering both the tissue reaction and the accompanying cytopathic changes. Knowledge of the patient’s immune status is also important, as some viral infections occur only in immunocompromised persons. Many viruses have unique ultrastructural findings that can be used for identification, although electron microscopy has been largely replaced by immunohistochemical staining using specific antibodies to viral components. Important contrasting features of selected viruses are listed in Table 7.1.

CYTOMEGALOVIRUS PNEUMONIA (CMV)

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) pneumonia occurs almost exclusively in immunocompromised persons with only rare cases reported in immunologically intact individuals. Pathologic diagnosis is essential because antiviral treatment needs to be instituted promptly, usually before culture results are available.

Histologic Features

Cellular enlargement with intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions

Cellular enlargement with intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions

Interstitial pneumonia, less commonly diffuse alveolar damage (DAD)

Interstitial pneumonia, less commonly diffuse alveolar damage (DAD)

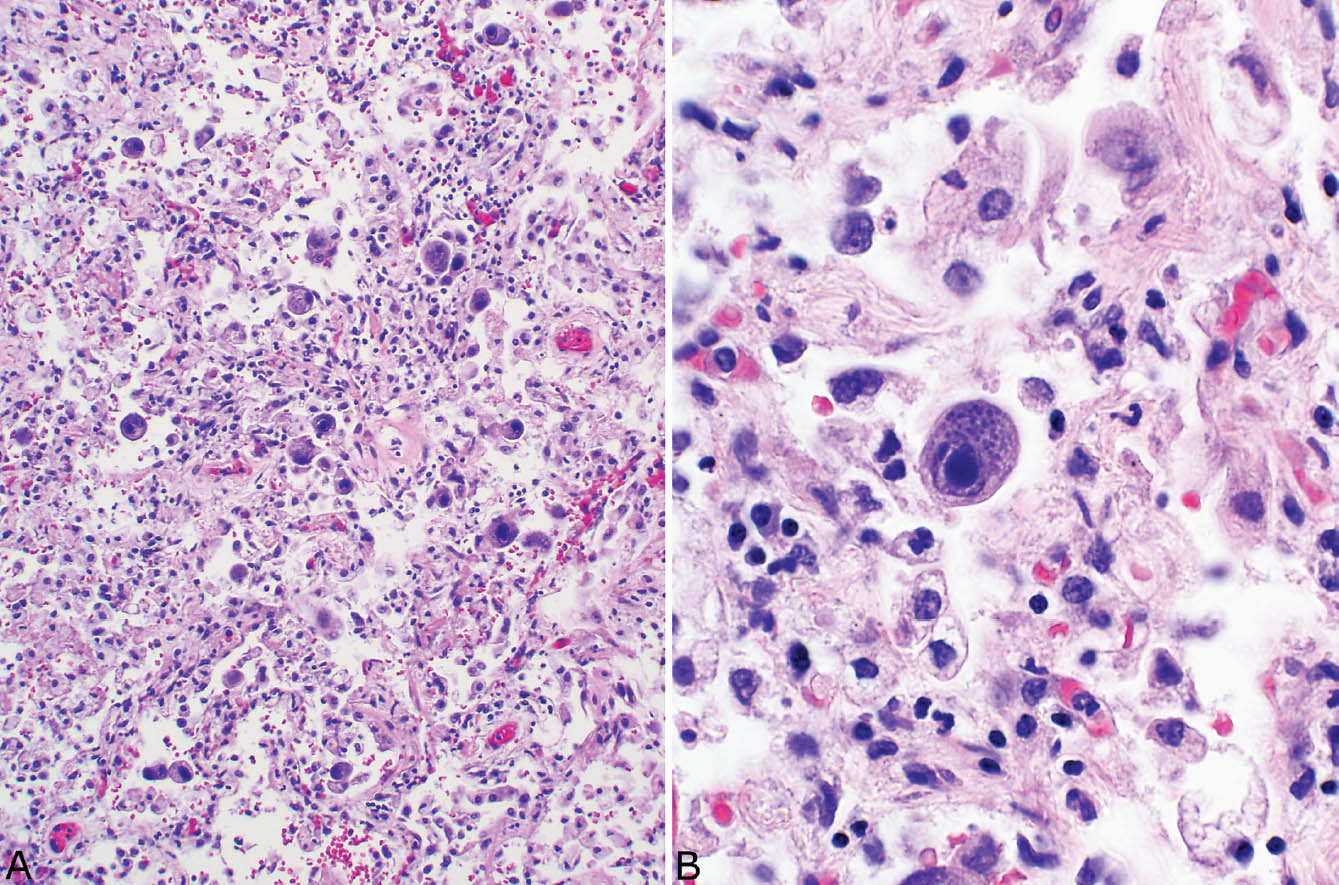

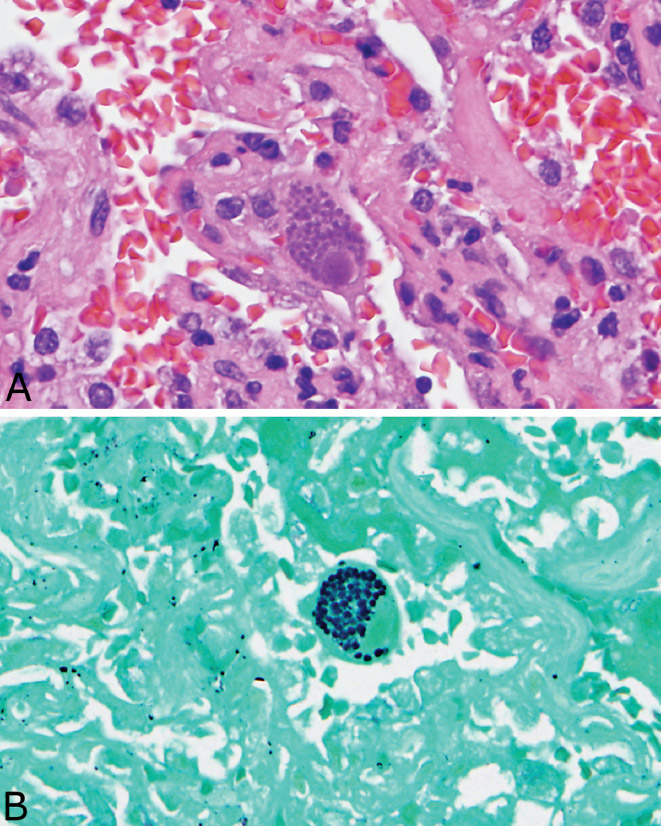

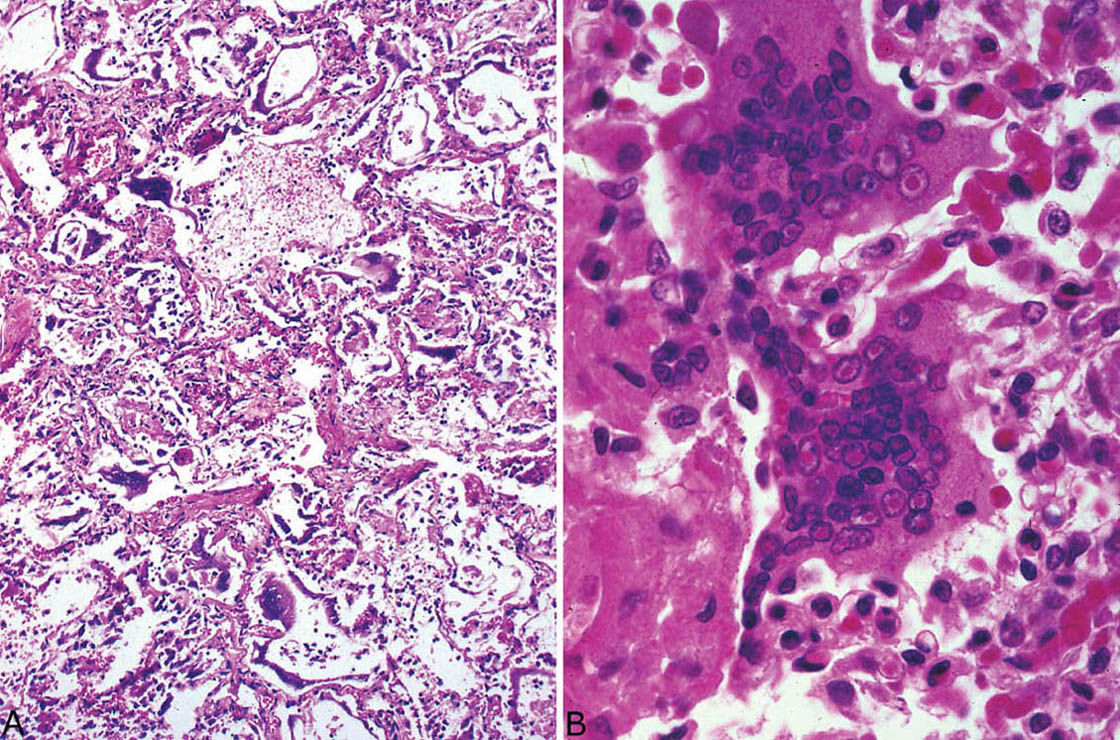

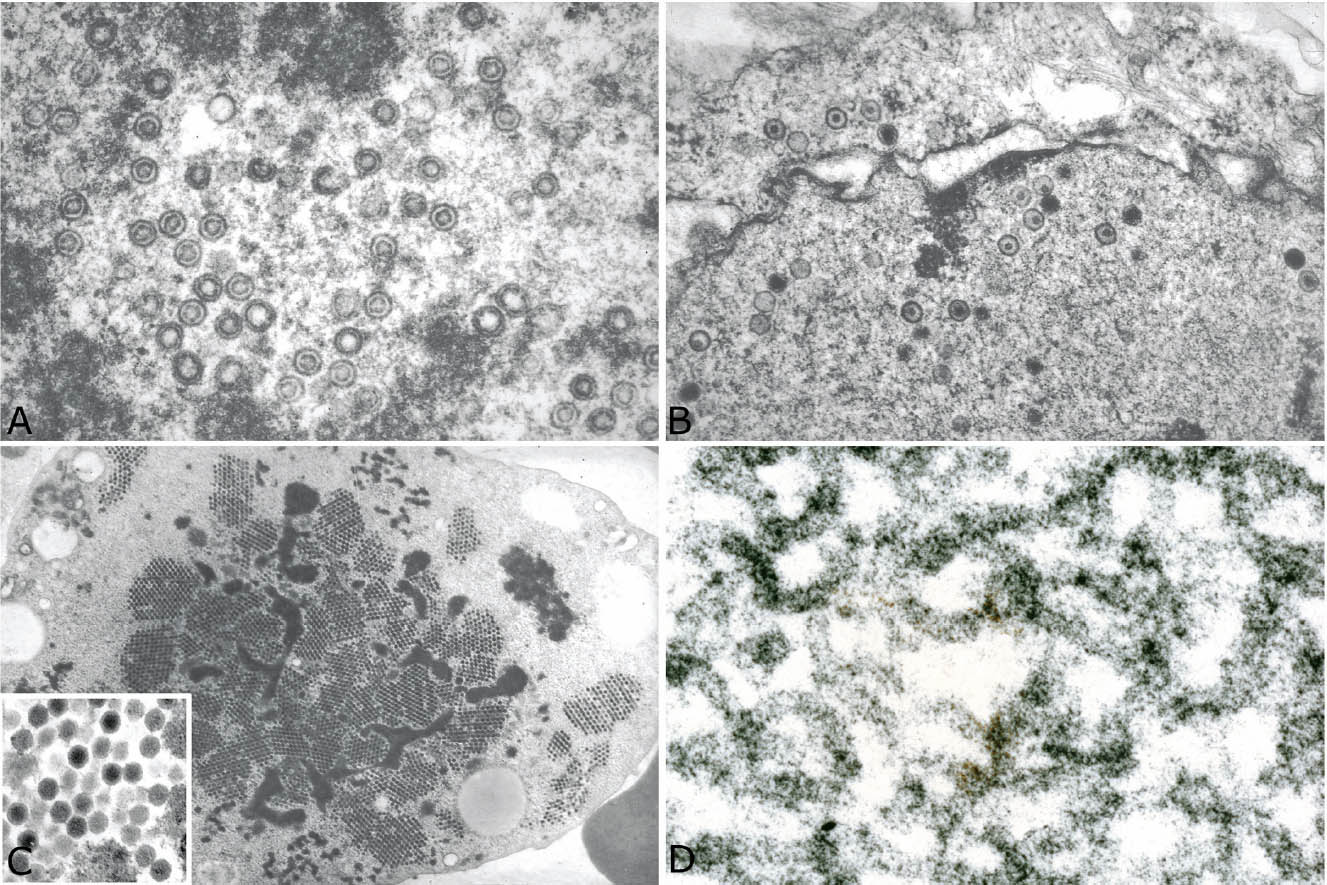

The histologic hallmark of CMV pneumonia is the presence of enlarged cells (cytomegaly) that contain both intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions (Figure 7.1). The intranuclear inclusions appear dark purple to basophilic and are separated from the surrounding chromatin by a clear halo, whereas the intracytoplasmic inclusions appear as coarse basophilic granules. Alveolar pneumocytes and alveolar macrophages are the cells most commonly showing the viral effect, although changes can also be present in bronchiolar epithelium and endothelial cells. If only endothelial cells are involved, however, disseminated CMV infection with secondary lung involvement is more likely than primary pneumonia. The intracytoplasmic inclusions contain a mucopolysaccharide envelope that stains positively in Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) stains (Figure 7.2), and should not be misinterpreted as fungal organisms. Commercially available immuno-histochemical stains are available and can be used to confirm the diagnosis of CMV infection. They are usually not necessary, however, and are not productive in cases lacking cytopathic changes in hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) stains. Ultrastructurally, the inclusions consist of viral particles measuring 100 to 200 nm and containing a clear to granular round core surrounded by a double membrane (see Figure 7.9A).

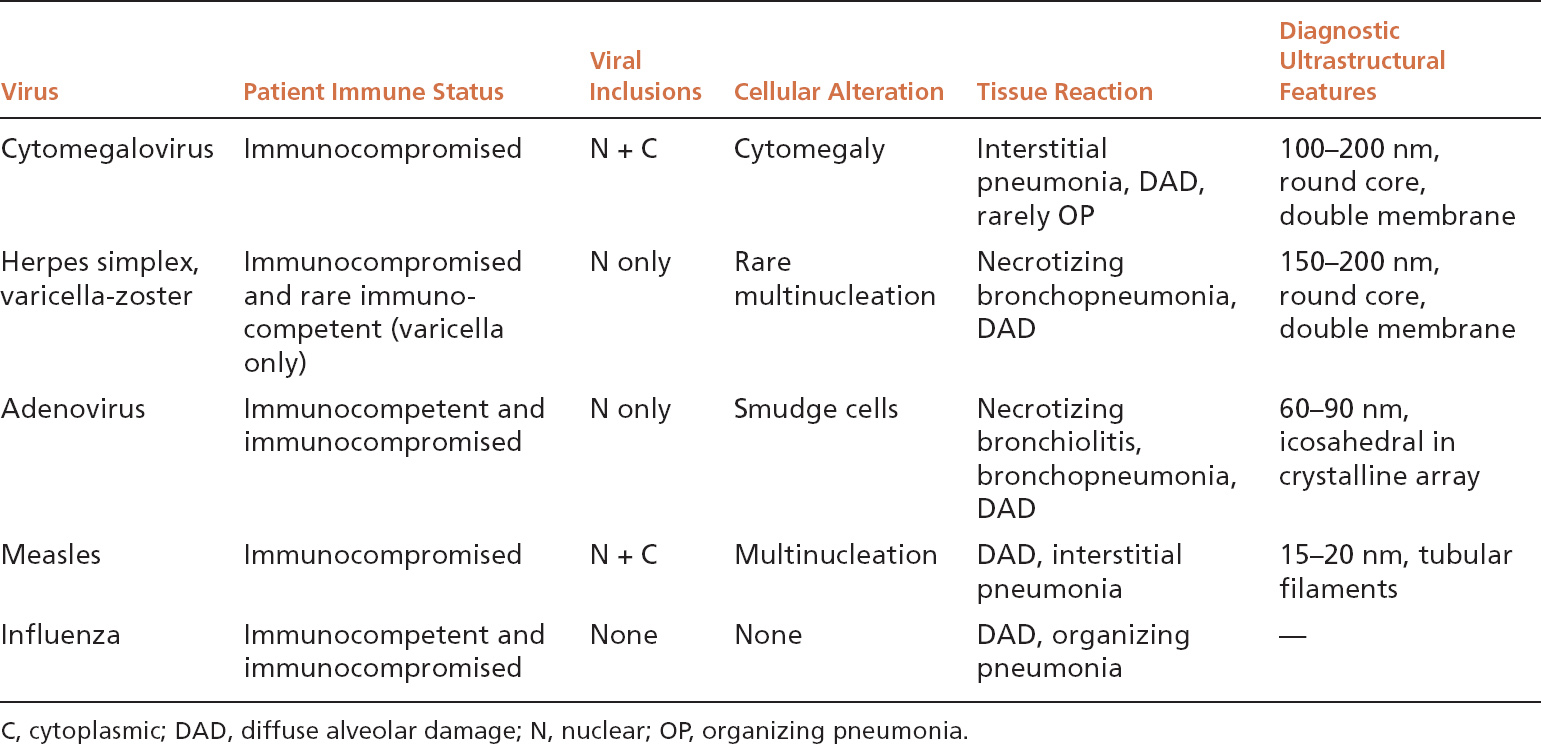

TABLE 7.1 Contrasting Features of Selected Viral Pneumonias

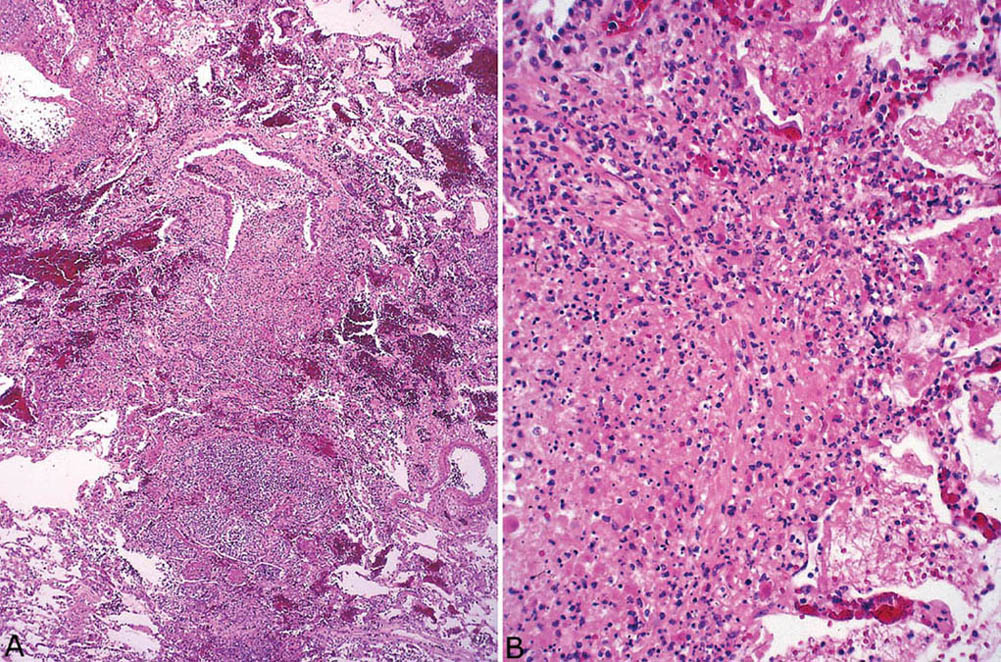

FIGURE 7.1 CMV pneumonia. (A) At low magnification, enlarged alveolar lining cells with darkly staining nuclei stand out within background cellular interstitial pneumonia. (B) The characteristic dark purple intranuclear inclusion and the basophilic granular intracytoplasmic inclusions are better visualized at high magnification. Note the large size of the involved cell compared with other cells in the field. CMV, cytomegalovirus.

The most common associated inflammatory reaction is a cellular interstitial pneumonia characterized by alveolar septal thickening by a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate along with alveolar pneumocyte hyperplasia (Figure 7.1). Less commonly, DAD (see Chapter 5) is encountered with prominent hyaline membrane formation, and there may be an associated interstitial chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate (Figure 7.3). Organizing pneumonia may be found in rare cases. Parenchymal necrosis is usually not a feature.

FIGURE 7.2 CMV inclusions. (A) Intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions are seen in this enlarged alveolar lining cell. (B) The intracytoplasmic inclusions stain strongly with GMS and should not be confused with fungal organisms. CMV, cytomegalovirus; GMS, Gomori methenamine silver.

Occasionally, cytopathic changes of CMV may be found in the absence of associated pathologic changes. This situation most likely reflects blood stream dissemination rather than a primary pneumonia, and its significance is clinically uncertain. CMV “pneumonia,” however, should be diagnosed only if the cytopathic changes are accompanied by the appropriate tissue reaction, including mainly interstitial pneumonia or DAD, or rarely organizing pneumonia.

Clinical Features

Among immunocompromised persons, recipients of bone marrow, heart–lung and other solid organ transplants, and HIV-infected individuals are especially susceptible to CMV pneumonia. Patients usually present with an acute febrile illness along with dyspnea and nonproductive cough. Diffuse lung infiltrates are usually present radiographically, although localized infiltrates have been described rarely. Mortality is high.

HERPES SIMPLEX/VARICELLA-ZOSTER PNEUMONIA

The histologic features of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster pneumonia are identical, and, therefore, they are discussed together.

Histologic Features

Necrotizing bronchopneumonia with bronchiolocentric distribution

Necrotizing bronchopneumonia with bronchiolocentric distribution

Intranuclear inclusions

Intranuclear inclusions

Herpes pneumonia is usually acquired via the airways, and, therefore, the lung changes center upon and spread from bronchioles. A necrotizing inflammatory reaction in which karyorrhexis from necrotic inflammatory and parenchymal cells is prominent destroys and replaces bronchioles and peribronchiolar parenchyma (Figures 7.4 and 7.5). DAD is often present in adjacent areas, and squamous metaplasia may be seen in residual bronchiolar epithelium. Cases lacking a bronchiolocentric distribution are rare and indicate a hematogenous spread to the lungs rather than an origin in the airways, a situation seen mainly in disseminated herpes simplex infection in newborns.

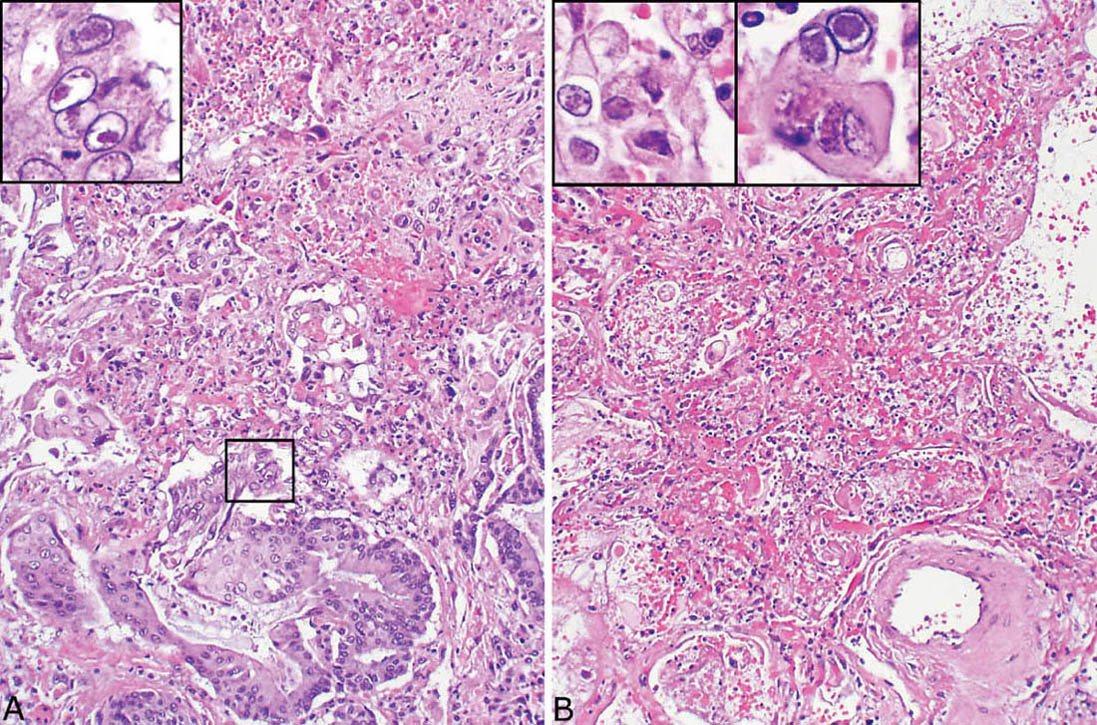

The diagnostic intranuclear inclusions of herpes virus may be difficult to identify because of the extensive necrosis, but searching within or around intact bronchiolar epithelium can be especially productive (Figure 7.5). The most typical and easiest to recognize inclusion is Cowdy type A characterized by a round, eosinophilic central body that is separated from the surrounding nuclear chromatin by a clear halo. It differs from the intranuclear inclusion of CMV in that it appears eosinophilic rather than basophilic, and cytomegaly is not present. Another type of intranuclear inclusion is characterized by dense, ground glass change that fills the nucleus and is surrounded by a basophilic rim. Such cells may have irregular nuclear borders, and they may be multinucleated with nuclear molding. As with CMV, immunohistochemical stains using commercially available antibodies can be used to confirm the diagnosis. Ultrastructurally, herpes inclusions are similar to those of CMV measuring 150 to 200 nm and consisting of a central dense core surrounded by a double membrane (see Figure 7.9B).

FIGURE 7.3 DAD in CMV pneumonia. (A) In this example, DAD with hyaline membrane formation is prominent. A dense interstitial chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate accompanies the DAD in areas. CMV-infected cells are visible at low magnification (arrows). (B) High magnification of a CMV-infected cell (left arrow in A) shows the typical large cell with intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions. Note the prominent associated chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. CMV, cytomegalovirus; DAD, diffuse alveolar damage.

FIGURE 7.4 Herpes virus pneumonia. (A) A low-magnification view illustrates the bronchiolocentric distribution of the necrotizing process with partial destruction of the bronchiole at top center and involvement of peribronchiolar parenchyma. (B) Higher magnification showing the characteristic marked karyorrhexis of the inflammatory cells and the necrotic parenchymal cells.

FIGURE 7.5 Herpes virus pneumonia. (A) Residual bronchiolar epithelium adjacent to necrotic parenchyma has undergone squamous metaplasia in this case, and Cowdry type A intranuclear inclusions are seen (boxed area at high magnification in the inset). (B) In another field from the same case, the bronchiole (identified only by the location of the changes next to an artery at bottom) is completely destroyed and replaced by the characteristic karyorrhectic necrosis. The inset at top left is a high magnification showing irregular-shaped ground glass intranuclear inclusions partially rimmed by dense chromatin, while a multinucleated cell with Cowdry type A inclusions is present in the right inset.

Although active varicella pneumonia is similar to herpes simplex pneumonia, necrotic nodules sometimes containing calcification have been described in healing or healed varicella (chicken pox) pneumonia.

Clinical Features

Herpes simplex pneumonia occurs almost exclusively in immunocompromised persons, although severely ill burn patients are also susceptible. Immunocompetent persons may acquire tracheobronchial infection from prolonged intubation, but lung involvement is rare. Herpes simplex lung infection may also be found rarely in newborn infants as part of disseminated hematogenous infection. Mortality rates are high.

Varicella pneumonia occurs in immunocompetent as well as immunocompromised persons. Pulmonary infiltrates occur in about 15% of patients with chicken pox, most of whom are adults. Most children with varicella pneumonia are immunocompromised, whereas most adults are immunocompetent. The diagnosis is usually made clinically as the characteristic rash of chicken pox generally precedes the development of pneumonia. Radiographically diffuse nodular infiltrates are typical. Mortality ranges from 10% to 30% depending of the patient’s immune status.

Disseminated herpes zoster occurs predominantly in immunocompromised persons and patients with underlying malignancy. Hodgkin disease patients are particularly susceptible. Skin dissemination is the usual manifestation and is associated with low mortality. Lung involvement is uncommon.

ADENOVIRUS PNEUMONIA

Adenovirus infection is usually confined to the upper respiratory tract and associated with mild flulike symptoms. Rarely, however, it causes serious pneumonia in immunologically intact as well as in immunocompromised individuals.

Histologic Features

Necrotizing bronchiolitis and bronchopneumonia

Necrotizing bronchiolitis and bronchopneumonia

Intranuclear inclusions

Intranuclear inclusions

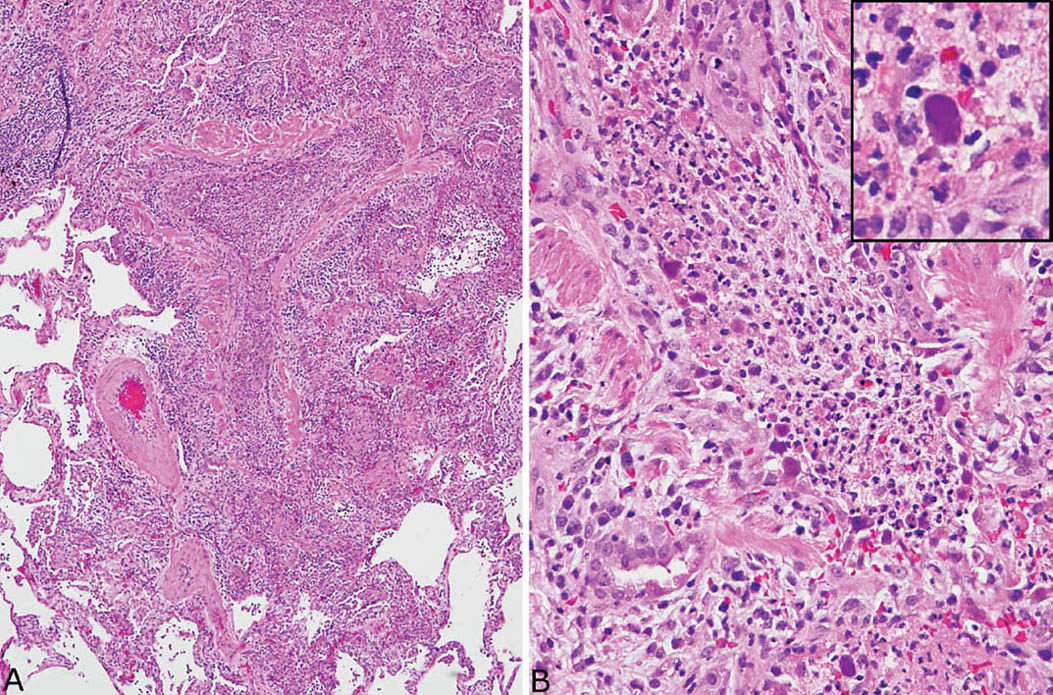

The histologic features of adenovirus pneumonia are similar to those of herpes pneumonia. The process is bronchiolocentric and characterized by acute inflammation and necrosis with prominent karyorrhexis that involve bronchioles and extend into adjacent parenchyma (Figure 7.6). Bronchiolar epithelium is sloughed and an acute inflammatory and necrotic cellular exudate fills their lumens. The necrotic inflammatory exudate extends variably beyond the affected bronchioles. The appearance differs from herpes pneumonia only in the relative predominance of bronchiolar over the pneumonic (alveolar) involvement, but this difference is minor. As with herpes pneumonia, DAD can also be found in the more distal parenchyma (Figure 7.7).

The clue to diagnosis is in identifying the characteristic intranuclear inclusions which, unfortunately, show some overlapping features with herpes inclusions (Figures 7.6B and 7.7B). “Smudge cells” are the most typical finding and are characterized by mild cellular enlargement and replacement of normal nuclear chromatin with a homogeneous, densely staining, amphophilic to basophilic intranuclear inclusion. Unlike similar inclusions in herpes virus infection, a distinct peripheral rim of condensed chromatin is usually not present and the nuclei remain round rather than irregular and distorted. A second type of intranuclear inclusion is round, eosinophilic, and separated from the nuclear membrane by a clear halo. It resembles a Cowdry type A inclusion, but is smaller and may be difficult to distinguish from a prominent nucleolus. Both inclusions are most easily identified in residual epithelium of affected bronchioles although they can also be found elsewhere in inflamed parenchyma. Ultrastructurally, adenovirus inclusions are easily distinguished from those of herpes virus (see Figure 7.9C). They are composed of icosahedral particles with a central, dense core and an outer coat that measure 60 to 90 nm and are arranged in a striking lattice-like or crystalline array. Knowledge of the patient’s immune status should also help in the differential diagnosis because herpes pneumonia occurs almost exclusively in immunocompromised persons, whereas adenovirus pneumonia may occur in immunologically intact, previously healthy individuals. As with herpes pneumonia, immunostains using commercially available antibodies can be used to confirm the diagnosis.

FIGURE 7.6 Adenovirus pneumonia. (A) A necrotizing bronchiolitis is seen in this area. Note the destruction of bronchiolar epithelium and the filling of the lumen by acute inflammatory cells that have spread into surrounding parenchyma. (B) A higher magnification view of the inflamed bronchiole highlights the necrotic intraluminal acute inflammatory cell exudate and the denudation of the epithelium. Typical “smudge” cells of adenovirus infection are noted along the bronchiole wall, and one is shown at higher magnification in the inset. Note the complete replacement of the nuclear contents by the homogeneous darkly staining inclusion.

Clinical Features

Pneumonia is a rare complication of adenovirus upper respiratory tract infection, but it carries a high mortality rate approaching 40%. Most deaths occur in children under the age of 1 year, but deaths have been reported in adults, including both previously healthy and immunocompromised. Peribronchiolar scarring with subsequent development of constrictive bronchiolitis obliterans (see Chapter 11) is a rare complication in some survivors.

MEASLES PNEUMONIA

Clinically apparent pneumonia is an uncommon complication of measles infection, usually occurring in immunocompromised children or less often adults. A rash is usually present, but rare cases reported without rash have been termed “giant cell pneumonia.”

Histologic Features

Large multinucleated giant cells with intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions

Large multinucleated giant cells with intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions

Interstitial pneumonia, DAD, and necrosis common

Interstitial pneumonia, DAD, and necrosis common

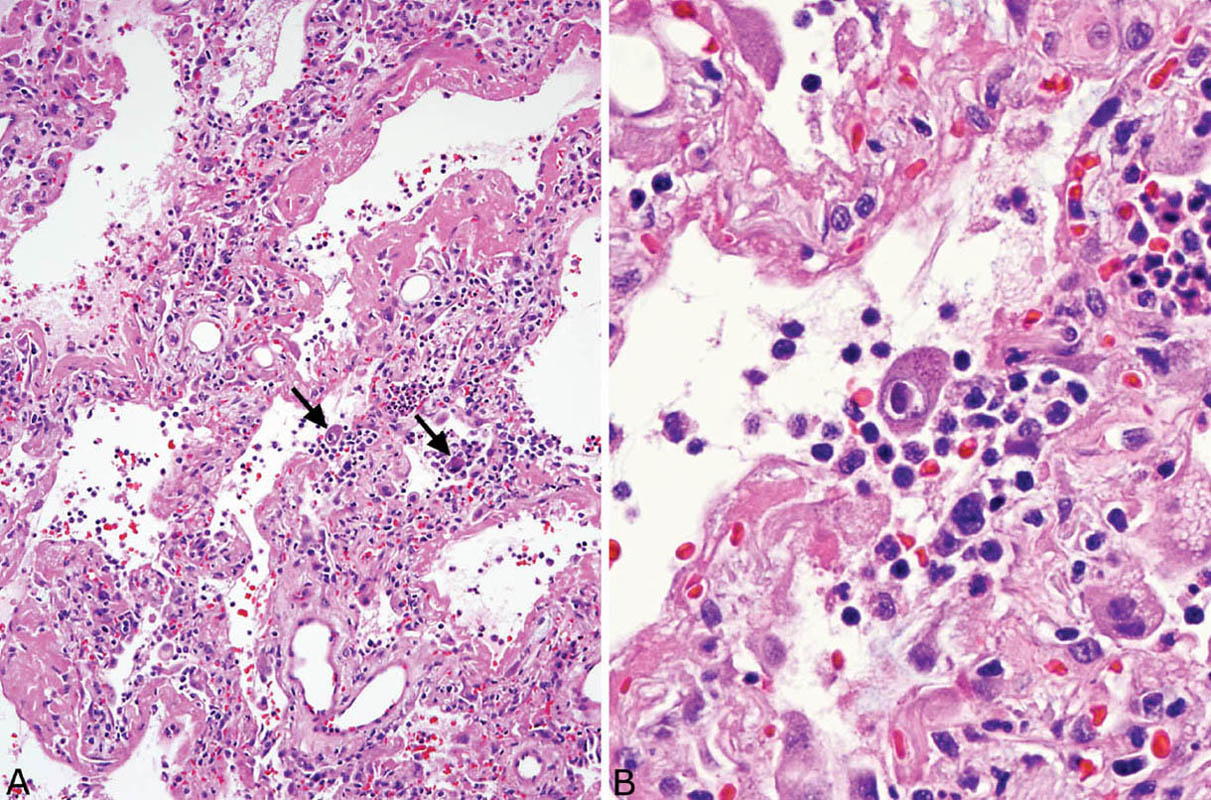

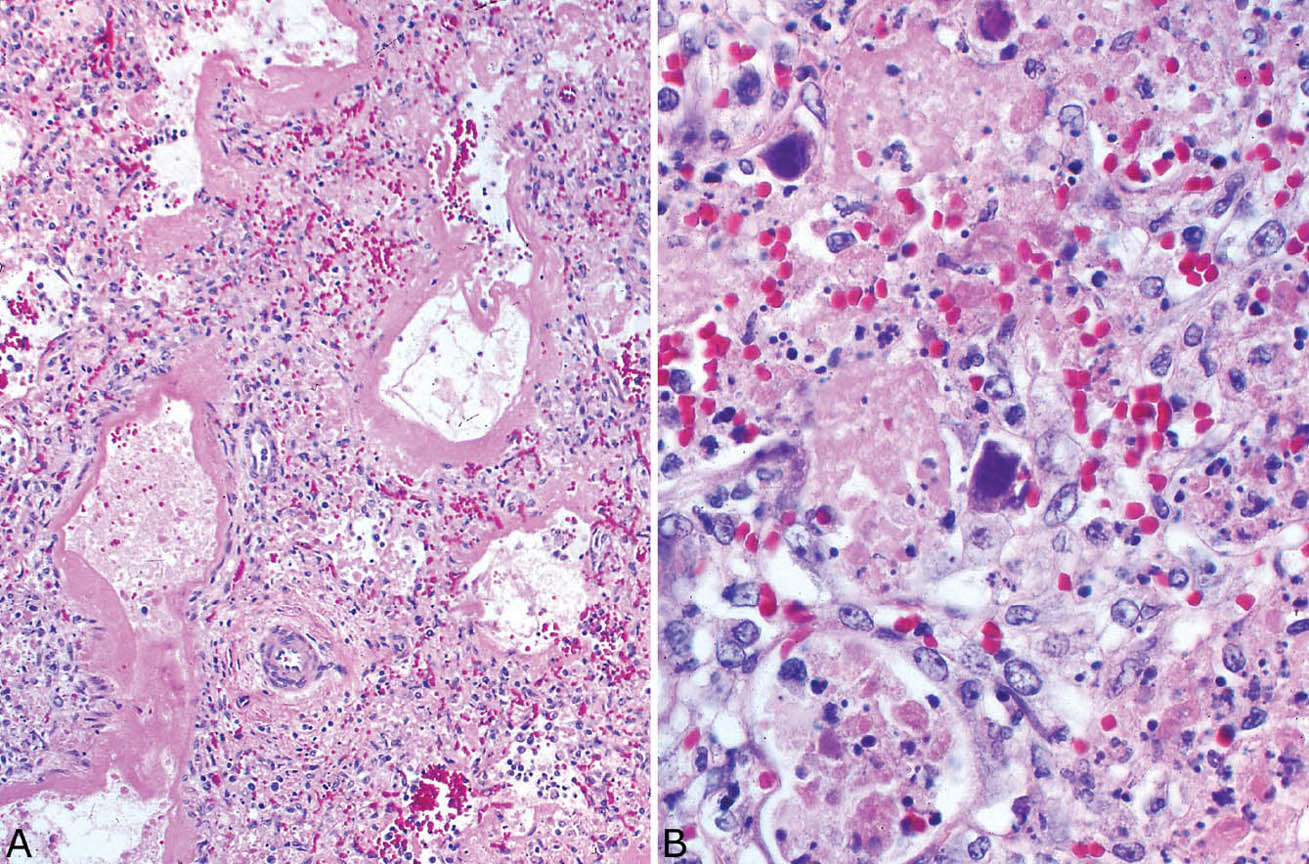

The most striking histologic finding in measles pneumonia is the presence of numerous large, multinucleated giant cells lining alveolar septa and detached within airspaces (Figure 7.8). The cells contain large numbers of nuclei with up to 60 reported in some cases, and they are present within abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. The cells are thought to form from fusion of alveolar lining cells. Both intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions are characteristic. The intranuclear inclusions resemble small Cowdry type A with a central eosinophilic structure separated by a clear halo from peripheral condensed chromatin. The ultrastructural features are distinct with tightly packed tubules measuring from 15 to 20 nm in diameter and having 6 nm cross-striations when viewed longitudinally (Figure 7.9D).

The giant cells occur in a background of DAD often accompanied by a cellular interstitial pneumonia. Focal necrosis may be found, and nonspecific squamous metaplasia is common in bronchiolar epithelium.

INFLUENZA AND OTHER VIRAL PNEUMONIAS

There are a number of other viral pneumonias that may rarely undergo lung biopsy, but in which specific diagnostic cytopathic effects are absent. The most common one is influenza pneumonia, while pneumonia caused by parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus, Hanta virus, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) corona virus, and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) virus is relatively rare. Histologically, most show varying features of DAD. Squamous metaplasia is common in bronchiolar epithelium, and a necrotizing bronchiolitis may sometimes accompany the other findings. Organizing pneumonia may occur in later stages, especially in influenza pneumonia, and immature lymphoid cells may be prominent in Hanta virus pneumonia. The diagnosis can be confirmed in some cases by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing or in situ hybridization for viral markers, and monoclonal antibodies are available in a few cases for immunohistochemistry. Viral particles have been reported by electron microscopy in SARS cases. The results of cultures and serologic tests are important to confirm the diagnosis, but not immediately available.

FIGURE 7.7 Adenovirus pneumonia. (A) In this example, DAD with hyaline membrane formation accompanies the typical karyorrhexis. (B) At higher magnification, the characteristic mildly enlarged smudge cells that formed from alveolar pneumocytes are seen. The typical intranuclear inclusions completely replace normal chromatin and obliterate the nuclear membrane (compare with herpes inclusions, Figure 7.5B, left inset). Note the background necrosis with conspicuous karyorrhexis. DAD, diffuse alveolar damage.

FIGURE 7.8 Measles pneumonia. (A) Numerous large, multinucleated giant cells are seen within background DAD. (B) Higher magnification of the characteristic giant cells showing large numbers of nuclei with prominent intranuclear inclusions. Intracytoplasmic inclusions are not seen in this field. DAD, diffuse alveolar damage.

FIGURE 7.9 Comparative ultrastructural findings in viral pneumonias. (A) CMV, (B) herpes virus, (C) adenovirus, and (D) measles virus (see text for details). CMV, cytomegalovirus.

Clinically, patients present with fever, dyspnea, and bilateral lung infiltrates. When features of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) intervene, mortality is high. RSV and parainfluenza pneumonia occur mainly in children, whereas in adults parainfluenza is seen mainly in immunocompromised individuals. In Hanta virus and SARS pneumonia, gastrointestinal symptoms are common in addition to respiratory complaints, and there may be accompanying hematologic abnormalities including thrombocytopenia and lymphopenia.

Helpful Tips—Viral Pneumonias

Diagnose CMV “pneumonia” only if appropriate tissue reaction is present; do not diagnose “pneumonia” if only cytopathic features are present in otherwise normal lung.

Diagnose CMV “pneumonia” only if appropriate tissue reaction is present; do not diagnose “pneumonia” if only cytopathic features are present in otherwise normal lung.

Cytopathic changes occurring only in endothelial changes usually indicate disseminated hematogenous CMV infection, not primary CMV pneumonia.

Cytopathic changes occurring only in endothelial changes usually indicate disseminated hematogenous CMV infection, not primary CMV pneumonia.

Some histologic features of herpes and adenovirus pneumonia may overlap; knowledge of the patient’s immune status helps in their differentiation, as herpes pneumonia is almost always associated with immune compromise.

Some histologic features of herpes and adenovirus pneumonia may overlap; knowledge of the patient’s immune status helps in their differentiation, as herpes pneumonia is almost always associated with immune compromise.

DAD is a common reaction to many viruses; look for diagnostic cytopathic changes and other less specific clues to diagnosis (bronchiolitis and necrosis with karyorrhexis).

DAD is a common reaction to many viruses; look for diagnostic cytopathic changes and other less specific clues to diagnosis (bronchiolitis and necrosis with karyorrhexis).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree