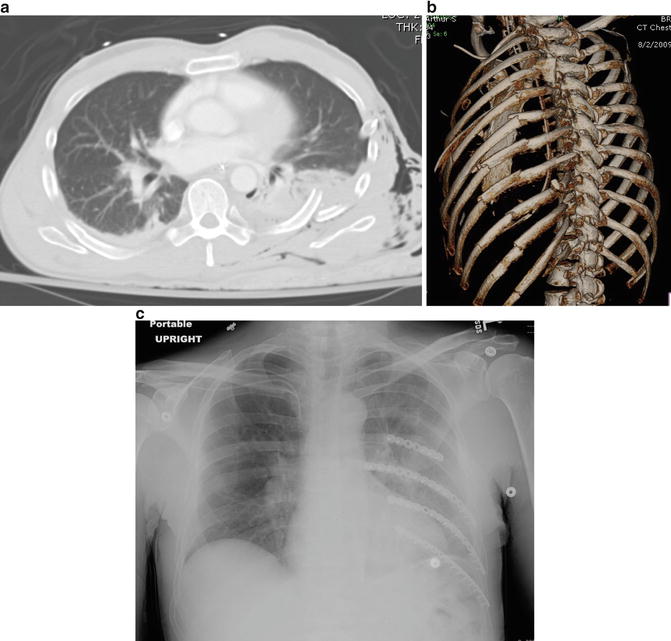

Fig. 7.1

(a) A patient with a severe chest wall injury with a number of indications for surgery including severe deformity with a flail segment, inability to wean from a ventilator, intraparenchymal lung penetration, and severe respiratory compromise. (b) A CT scan of the chest demonstrating the severity of the injury. (c, d) We have found three-dimensional CT scan reconstruction to be very valuable in the assessment of these injuries as it enables the surgeon to grasp the overall clinical deformity, evaluate the fixation required for each rib, anticipate potential obstructions (i.e., the scapula), and plan the surgical approach. (e) An intraoperative photograph demonstrating fixation of the three most displaced ribs through a lateral thoracotomy type approach. It is not necessary to plate every rib in this setting: simply repairing enough to stabilize the flail segment is the operative goal. (f) Comparative preoperative and postoperative radiographs demonstrating the successful re-establishment of chest wall dimensions and contours. The patient received operative care on post-injury day 3, extubated on post-injury day 4, and discharged on post-injury day 7 (Case courtesy of W. Drew Fielder, MD FACS)

Current opinion is changing however, as three recent randomized, controlled trials [9–11] as well as a meta-analysis [12] present strong arguments for both short- and long-term benefits following operative management of the FC.

A current review of the relative indications and contraindications for the fixation of chest wall injuries is presented. However, further research with randomized, controlled trials is urgently needed in this controversial field.

Indications

Anterolateral Flail Chest with Respiratory Failure and Without Significant Underlying Pulmonary Contusion

The most common indication for surgical fixation of an FC, and that with the strongest evidential support, is for respiratory failure with an anterolateral flail segment without severe underlying pulmonary contusion (PC) [4, 9, 10, 13, 14]. Patient profiles from two randomized clinical trials on this topic were consistent with this indication. Tanaka et al. described a group of 18 FC patients being ventilated for acute respiratory failure whose chest wall injuries were managed surgically with Judet struts. Their outcomes were compared to randomized controls managed nonoperatively. Approximately two-thirds of the patients had a mild or moderate underlying lung contusion. They found short- and long-term benefits to operative repair, including a decrease in duration of ventilatory support, decreased length of stay (LOS) in the intensive care unit (ICU), lower rates of pneumonia, improved pulmonary function tests (PFTs), and decreased time to return to work [9]. Marasco et al.’s 23 operative patients did not have severe PC underlying their FC and were managed with resorbable rib-specific plates. All patients were already ventilated with no prospect of weaning for the next 48 h. Their time of ventilatory support and ICU LOS were also significantly reduced following fixation [10] (Fig. 7.2).

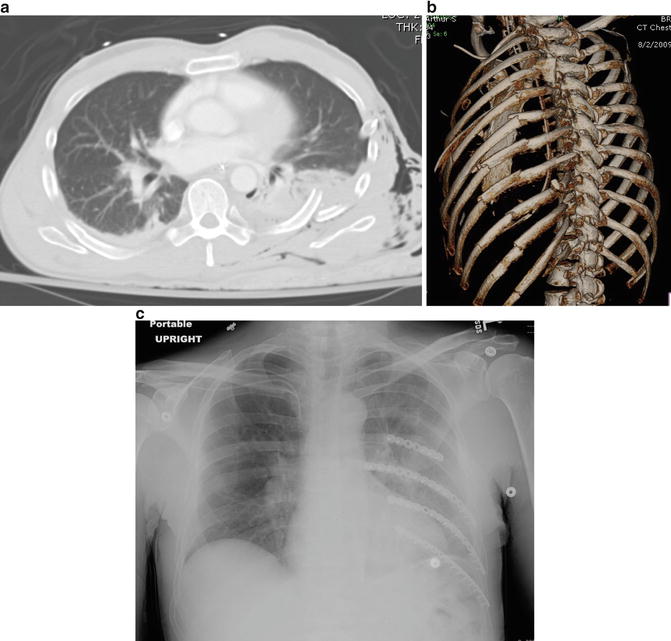

Fig. 7.2

(a) A CT scan of a patient with chest wall injury, multiple consecutive rib fractures, and a flail segment. The actual morphology of the fractures is difficult to determine from the plain CT scan. (b) The three-dimensional reconstruction scan demonstrates the overall pattern and location of the fractures and specifically the segmental nature of the more inferior rib fractures. This type of information assists in surgical planning and implant selection. (c) Surgical fixation of the flail segment was performed: the segmental fractures required the use of longer implants to span both fracture sites (Case courtesy of W. Drew Fielder, MD FACS)

Level II studies also support this indication. Lardinois et al. conducted a prospective trial in which 66 patients with anterolateral FC had fixation with 3.5 mm pelvic reconstruction plates. They found greater than expected improvement in PFTs at 6 months and found patients with anterolateral FC with respiratory failure and minimal lung contusion recovered exceptionally well. In particular, they recommended early intervention in elderly patients meeting these criteria in order to avoid prolonged ventilatory support and to preserve thoracic physiology. They noted the elderly is at particular risk for rapid deterioration with what may seem to be a relatively minor injury, but, due to their limited reserve, do not fare well after traumatic injuries [13].

When contemplating surgical fixation of a chest wall injury, the absence of severe underlying PC may be particularly important. Altered physiology has been demonstrated following these injuries [15, 16] that results in a lesser benefit to surgical fixation, as evidenced by a lack of improvement in length of mechanical ventilation when compared to matched controls [17].

Respiratory Compromise in Non-intubated Patients

Operative repair is not limited to patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Early signs of respiratory compromise in non-intubated FC patients should prompt assessment of the patient’s progress or deterioration, trauma physiology, and how well they would tolerate mechanical ventilation. Respiratory status can be monitored by arterial blood gas evaluation and observed clinically and radiographically. Haasler et al. supports chest wall stabilization for progressive chest cavity shrinkage as observed on sequential chest radiographs [18]. In a prospective study by Granetzny et al., 20 non-intubated FC patients were randomized to surgical or nonsurgical management, and significant improvements were seen in ventilator days, ICU LOS, total LOS, rates of pneumonia and deformity, as well as PFTs at 2 months in the operative group [11]. Althausen et al. showed the same short-term improvements in their retrospective case-controlled study with locking reconstruction plates in non-intubated patients with respiratory compromise in spite of appropriate analgesic measures and maximal nonoperative measures [4]. In these patients, surgical stabilization allows for improvement in respiratory dynamics through chest wall stabilization, leading to better pain control, allowing more efficient secretion clearance [13].

Thoracotomy for Other Indications

The “on the way out” strategy is a more traditional indication for fixation. This term describes the fixation of associated rib fractures upon exit from the chest cavity during a thoracotomy performed for other indications (see below). Molnar describes it as the only definite indication for FC fixation [19]. The Eastern Association of the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) Practice Management Guidelines on FC gives this a Level III recommendation [20]. Scenarios in which thoracotomy may be indicated include massive acute hemothorax (>1,500 ml immediately after thoracostomy tube placement or >200 ml/h output from a chest tube for 3 h [21]), cardiovascular injury, tracheobronchial injury, diaphragm injury, pulmonary laceration with ongoing air leak, or retained hemothorax (Chap. 11). The authors of many studies support this practice: [1, 3, 17, 22–26] however, less than one in five surgeons who manage acute trauma patients in the USA describes this as a valid indication [8].

Failure to Wean from Mechanical Ventilation

Intubated FC patients who are failing to wean from the ventilator, as mentioned above, should also be considered for operative fixation. While only a third of surveyed surgeons endorse this indication [8], and supporting evidence is limited to expert opinion, this has traditionally been an accepted indication [1, 26, 27]. With new technologies and new studies being produced on a regular basis, however, it is anticipated that, while this will remain an operative indication, it will not be the primary one. Secondary benefit may also be achieved in patients with underlying PC who have persistent flail segments and are failing to wean from the ventilator [13]. It is difficult to outline specific indications for fixation in this setting: there are a variety of factors that will influence the decision in this regard. In general, a failure of a ventilated patient to improve with time, and with no reasonable expectation for doing so, represents a relative indication for fixation. This is a decision that should be made after a multidisciplinary discussion involving the traumatologist, surgeon, and intensivist (Table 7.1).

Table 7.1

Summary of indications for flail chest fixation and level of supporting evidence

Indication | References | Strongest level of evidence |

|---|---|---|

Anterolateral flail chest with respiratory failure and without significant underlying pulmonary contusion | Tanakaa, Marascoa, Althausen, Lardinois, Davignon | Randomized controlled trial (Level I) |

Respiratory compromise in non-intubated patients | Granetznya, Althausen, Haasler, Lardinois, Pettiford | Randomized controlled trial (Level I) |

Thoracotomy for other indications | Althausena, Ahmeda, Nirula 2010, Teng, Mayberry, Molnar, Voggenreiter, EAST, McDowell, Moore, Paris, Pettiford | Retrospective case-controlled study (Level III) |

Failure to wean from mechanical ventilation | Althausena, Nirula 2006a, Nirula 2010, Mayberry, EAST, Pettiford | Retrospective case-controlled study (Level III) |

Deformity too significant to heal spontaneously | Althausena, Moore, Pettiford | Retrospective case-controlled study (Level III) |

Intractable pain

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|