An increasing hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level portends an adverse cardiovascular prognosis; however, the association between glycemic control, platelet reactivity, and outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with drug-eluting stents (DES) is unknown. We sought to investigate whether HbA1c levels are associated with high platelet reactivity (HPR) in patients loaded with clopidogrel and aspirin, thereby constituting an argument for intensified antiplatelet therapy in patients with poor glycemic control. In the prospective, multicenter Assessment of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy With Drug Eluting Stents registry, HbA1c levels were measured as clinically indicated in 1,145 of 8,582 patients, stratified by HbA1c <6.5% (n = 551, 48.12%), 6.5% to 8.5% (n = 423, 36.9%), and >8.5% (n = 171, 14.9%). HPR on clopidogrel and aspirin was defined after PCI as P2Y12 reaction units (PRU) >208 and aspirin reaction units >550, respectively. HPR on clopidogrel was frequent (48.3%), whereas HPR on aspirin was not (3.9%). Patients with HbA1c >8.5% were younger, more likely non-Caucasian, had a greater body mass index, and more insulin-treated diabetes and acute coronary syndromes. Proportions of PRU >208 (42.5%, 50.2%, and 62.3%, p <0.001) and rates of definite or probable stent thrombosis (ST; 0.9%, 2.7%, and 4.2%, p = 0.02) increased progressively with HbA1c groups. Clinically relevant bleeding was greatest in the intermediate HbA1c group (8.2% vs 13.1% vs 9.5%, p = 0.04). In adjusted models that included PRU, high HbA1c levels (>8.5) remained associated with ST (hazard ratio 3.92, 95% CI 1.29 to 12.66, p = 0.02) and cardiac death (hazard ratio 4.24, 95% CI 1.41 to 12.70) but not bleeding at 2-year follow-up. There was no association between aspirin reaction units >550 and HbA1c levels. In conclusion, in this large-scale study, HbA1c and HPR were positively associated, but the clinical effect on adverse outcome was driven by poor glycemic control, which predicted ST and cardiac death after PCI regardless of PRU levels, warranting efforts to improve glycemic control after DES implantation in patients with diabetes mellitus.

Key aspects of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) such as insulin resistance, metabolic abnormalities including hyperglycemia, and oxidative stress and inflammation all increase platelet reactivity. High platelet reactivity (HPR) in patients on treatment with clopidogrel is a well-described predictor of adverse thrombotic events after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Additionally, a number of studies have established that increasing hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels portend an adverse cardiovascular prognosis, and a few reports have shown an association between HPR and DM. These findings may imply that HPR is a driver of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with hyperglycemia and that intensified platelet inhibition is needed in patients with elevated HbA1c levels undergoing PCI. Nonetheless, the association between DM or abnormal glycemic control, platelet reactivity, and outcomes after PCI with drug-eluting stents (DES) is still unclear. Previous studies examining the outcomes of intensified platelet inhibition in subjects with DM have demonstrated conflicting results. In addition, several recent studies have been unable to demonstrate an independent correlation between HbA1c levels and (1) platelet reactivity or (2) lower platelet aggregation after intensive glycemic control in patients with long-standing uncontrolled DM, suggesting that glycemic control does not influence platelet reactivity. The aim of the present study was to first investigate whether HbA1c levels were independently associated with HPR in a large-scale cohort of patients loaded with clopidogrel and aspirin, and second, to investigate whether the association between HgbA1c and clinical outcomes was mediated by HPR, thereby constituting an argument for intensified antiplatelet therapy in patients with poor glycemic control.

Methods

The present study is a dedicated analysis of the prospective, multicenter Assessment of Dual AntiPlatelet Therapy With Drug Eluting Stents (ADAPT-DES) registry. HbA1c levels were measured at the discretion of the treating physician at the enrolling site and were therefore collected in 1,145 of 8,582 enrolled patients.

The design of the ADAPT-DES registry has previously been described in detail. Aspirin was given as either (1) a non–enteric-coated oral dose of 300 mg or more at least 6 hours before PCI or (2) a chewed dose of 324 mg or intravenous dose of 250 mg or more at least 30 minutes before PCI. Clopidogrel was given as either (1) a dose of 600 mg at least 6 hours before platelet reactivity testing, (2) a dose of 300 mg at least 12 hours before platelet reactivity testing, or (3) a dose of 75 mg or more for at least 5 days before platelet reactivity testing. Platelet reactivity was assessed after successful PCI and after an adequate period to ensure full antiplatelet effect using the VerifyNow Aspirin and P2Y12 assays (Accumetrics, San Diego, California). If eptifibatide or tirofiban was used during PCI, a 24-hour washout period was required before platelet reactivity testing. A 10-day washout period was required if abciximab was used, and thus, no patients receiving abciximab were enrolled. After PCI, patients were treated with aspirin indefinitely, and clopidogrel was recommended for at least 1 year.

Definite or probable stent thrombosis (ST) was defined according to the Academic Research Consortium criteria. Major adverse cardiac events (MACE) included cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI), or target lesion revascularization for ischemia or other symptoms. Additional end points included all-cause and cardiac mortality, MI, and clinically relevant bleeding. Clinically relevant bleeding was defined as the occurrence of any of the following: a Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction major or minor bleed, a GUSTO (Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Arteries) bleed, an ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage Strategy) major bleed, or any postdischarge bleeding event requiring medical attention.

We categorized patients by HbA1c <6.5% (n = 551, 48%), 6.5% to 8.5% (n = 423, 37%), and >8.5% (n = 171, 15%). The grouping of the HbA1c cut points was chosen a priori on the basis of several previous cohorts that identified an HbA1c level of 8.5% as being predictive of adverse cardiovascular events in diabetic populations. Andersson et al showed in 7,500 overweight patients with type 2 DM and/or cardiovascular disease and stratified by groups of 1 percentage point HbA1c increase, that cardiovascular risk was the lowest below 6.5%, similarly elevated for patients between 6.5% to 8.5%, and constantly increasing >8.5%. Similarly, Xu et al recently reported an HbA1c level of 8.5% to be independently predictive of cardiac adverse events.

HPR on clopidogrel was defined as P2Y12 reaction units (PRU) >208. The HPR cutoff was chosen as it has been previously validated in different cohorts and because the optimum PRU cutoff for both definite/probable and definite ST was determined to be 206 in the ADAPT-DES study. The cutoff for HPR on aspirin was >550 aspirin reaction units (ARU).

Demographic and baseline characteristics of HbA1c groups were compared using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the 1-way analysis of variance for continuous variables except for race, for which the Fisher’s exact test was used, and baseline ARU, which was highly skewed and compared with the Kruskal–Wallis test.

Predictors of HPR were identified using simple logistic regression with categorized HbA1c and a multivariate model chosen through a stepwise selection procedure with HbA1c level forced into the final model. The results are given as odds ratios and 95% CIs.

Adverse event rates were estimated using a Kaplan–Meier analysis and compared using the log-rank test; estimated failure rates and numbers of events are shown. Subsequently, Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) of HbA1c. Two adjusted models were constructed—one with HbA1c and PRU alone and one fully adjusted model using a stepwise selection procedure with entry and removal thresholds equal to 0.1 with HbA1c and PRU forced into the model. Because of the rarity of ST events, only the HbA1c-and PRU-adjusted model was estimated. In both the PRU and fully adjusted models, the interaction between PRU and HbA1c was tested but was never significant and was removed from the final models. The HRs and 95% CIs are given.

The proportional hazards assumption was checked for each of the final models, and the effect of HbA1c varied with time in the MACE and MI models; an interaction term between time and HbA1c was included in those models to correct the violations.

All analyses were conducted with SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) and plots were constructed in R, version 3.2.1, (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the ggplot2 package, version 1.0.0; a 2-sided significance level of 0.05 was used throughout.

Results

In the overall cohort of patients with available HbA1c levels, most of the patients (61%, 693 of 1,145) had known DM, of whom 38% (266 of 693) had insulin-treated DM. The median HbA1c for this study cohort was 6.5% (interquartile range 5.8 to 7.6). Patients with HbA1c >8.5% were significantly younger, more likely non-Caucasian, were more likely to be enrolled at a US site, had a higher body mass index, and more insulin-treated DM, acute coronary syndromes, and acute heart failure at the time of PCI (Killip’s class II to IV). Hypertension; hyperlipidemia; coronary artery disease in terms of previous MI, PCI, and coronary artery bypass grafting; peripheral artery disease; and previous heart failure were less present when HbA1c was <6.5%. The frequency of preprocedure aspirin and thienopyridine administration was highest in the mid HbA1c group ( Tables 1 and 2 ).

| Variable | Baseline Hemoglobin A1c (%) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <6.5 (n = 551) | ≥6.5 and ≤8.5 (n = 423) | >8.5 (n = 171) | ||

| Age (years) | 63 ± 11.2 | 64.9 ± 9.8 | 59.4 ± 10.6 | <0.0001 |

| Men | 426 (77%) | 306 (72%) | 122 (71%) | 0.36 |

| Race | 0.03 | |||

| White | 525 (95%) | 386 (91%) | 149 (87%) | |

| Black | 17 (3.1%) | 25 (5.9%) | 17 (9.9%) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 29 ± 5.4 (551) | 31.2 ± 6.4 (423) | 32.4 ± 6.1 (171) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 174 (32%) | 362 (86%) | 157 (92%) | <0.0001 |

| Diabetes: insulin or oral | 134 (24%) | 317 (75%) | 144 (84%) | <0.0001 |

| Oral only (no insulin) | 94/174 (54%) | 181/362 (50%) | 54/157 (34%) | <0.0001 |

| Insulin | 40/174 (23%) | 136/362 (38%) | 90/157 (57%) | |

| Diet or not treated | 40/174 (23%) | 45/362 (12%) | 13/157 (8.3%) | |

| Peripheral arterial disease (history) | 49 (8.89%) | 60 (14%) | 24 (14%) | 0.06 |

| Congestive heart failure (history) | 35 (6.35%) | 67 (16%) | 26 (15%) | <0.0001 |

| Previous myocardial infarction (>7 days percutaneous coronary intervention) | 119 (22%) | 115 (27%) | 50 (29%) | 0.14 |

| Previous coronary bypass | 70 (13%) | 88 (21%) | 31 (18%) | 0.008 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 202 (37%) | 188 (44%) | 71 (42%) | 0.14 |

| Renal insufficiency (history) | 46 (8.4%) | 55 (13%) | 20 (12%) | 0.17 |

| Dialysis | 8 (1.5%) | 8 (1. 9%) | 3 (1.8%) | 0.86 |

| Hypertension | 420 (76%) | 374 (88%) | 145 (85%) | <0.0001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 342 (62%) | 349 (83%) | 126 (74%) | <0.0001 |

| Smoker | ||||

| Never | 233 (42%) | 193 (46%) | 71 (42%) | 0.01 |

| Former | 162 (29%) | 151 (36%) | 48 (28%) | |

| Current | 156 (28%) | 79 (19%) | 52 (30%) | |

| United States site | 303 (55%) | 217 (51%) | 125 (73%) | <0.0001 |

| Variable | Baseline Hemoglobin A1c | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <6.5 (n = 551) | ≥6.5 and ≤8.5 (n = 423) | >8.5 (n = 171) | ||

| Killip class (at time of PCI): 2-4 | 14 (2.54%) | 9 (2.13%) | 12 (7.02%) | 0.01 |

| Stable angina | 169 (31%) | 156 (37%) | 29 (17%) | <0.0001 |

| Acute coronary syndromes | 318 (58%) | 203 (48%) | 113 (66%) | 0.0003 |

| Unstable angina | 100/318 (31%) | 85/203 (42%) | 46/113 (41%) | 0.007 |

| ST-segment elevation | 89/318 (28%) | 30/203 (15%) | 18/113 (16%) | |

| Non–ST-segment elevation | 129/318 (41%) | 88/203 (43%) | 49/113 (43%) | |

| Angina | 450 (82%) | 326 (77%) | 131 (77%) | 0.43 |

| Asymptomatic coronary artery disease | 22 (4%) | 45 (11%) | 19 (11%) | 0.0002 |

| Atypical chest pain | 33 (5.99%) | 34 (8.04%) | 24 (14.04%) | 0.009 |

| Degree of coronary artery disease >1 | 219 (40%) | 109 (26%) | 59 (35%) | <0.0001 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 57.2 ± 13.9 (462) | 51.7 ± 13.5 (268) | 50.8 ± 13.6 (142) | <0.0001 |

| >1 Vessels treated per patient | 493 (89%) | 345 (82%) | 151 (88%) | 0.004 |

| Location: Left anterior descending coronary artery | 250 (45%) | 202 (48%) | 77 (45%) | 0.72 |

| >1 Stent implanted | 227 (41%) | 184 (44%) | 75 (44%) | 0.71 |

| Lesion length, mm | 26.7 ± 19.4 (551) | 27.6 ± 20.8 (423) | 26.9 ± 18.8 (171) | 0.78 |

| Minimum pre-PCI TIMI flow = 1 or 0 | 56 (10.2%) | 31 (7.3%) | 17 (9.9%) | 0.86 |

| Minimum post-PCI TIMI flow = 3 | 550 (99.8%) | 420 (99.3%) | 170 (99.4%) | 0.37 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 14.1 ± 1.6 (548) | 13.6 ± 1.5 (422) | 13.7 ± 1.6 (171) | 0.0001 |

| Creatinine clearance <60 mL/min | 82 (15%) | 74 (18%) | 21 (12%) | 0.73 |

| White blood cell count, K/mL | 8.3 ± 2.8 (546) | 8 ± 2.5 (421) | 8.7 ± 2.9 (171) | 0.01 |

| Platelet count, K/mm 3 | 225.8 ± 59.7 (546) | 215.4 ± 57.7 (421) | 228 ± 72.1 (171) | 0.04 |

| Aspirin | ||||

| Pre-procedure | 492 (89%) | 403 (95%) | 152 (89%) | 0.002 |

| Prescribed at Discharge | 542 (99%) | 414 (98%) | 171 (100%) | 0.15 |

| Thienopyridine | ||||

| Pre-procedure | 420 (76%) | 365 (86%) | 125 (73%) | <0.001 |

| Prescribed at Discharge | 548 (99.6%) | 417 (98.6%) | 170 (99.4%) | 0.17 |

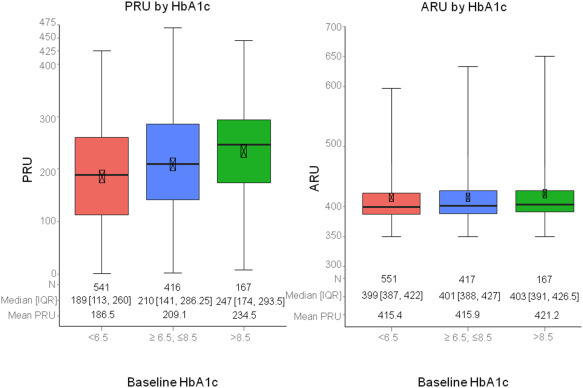

The median ARU values for each HbA1c group were similar (399.0 [387.0 to 422.0], 401.0 [388.0 to 427.0], and 403.0 [391.0 to 426.5 for HbA1c <6.5, ≥6.5 and ≤8.5, and >8.5, respectively; p = 0.08), whereas those for PRU increased significantly with increasing levels of HbA1c (189.0 [113.0, 260.0], 210.0 [141.0, 286.25], and 247.0 [172.0, 293.5], p <0.0001; Figure 1 ).

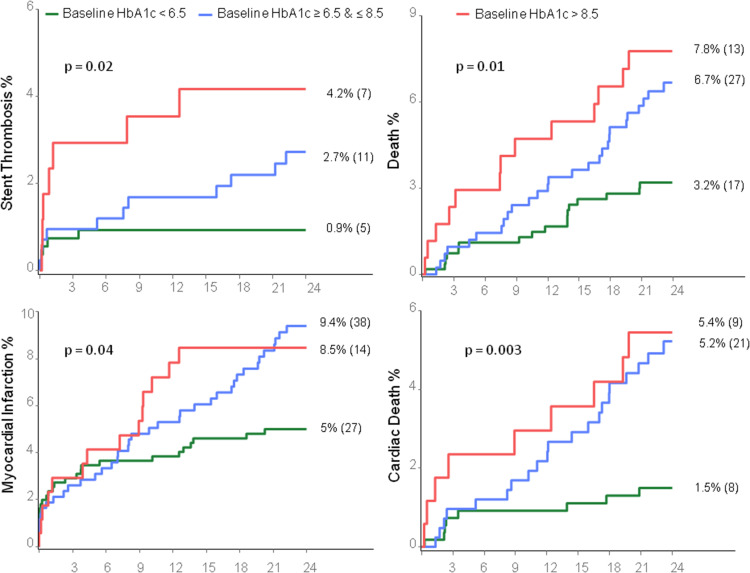

A total of 48% patients (543 of 1,124) had HPR on clopidogrel defined by PRU >208, whereas only 3.9% (44 of 1,135) had HPR on aspirin, defined by ARU >550. The proportion of PRU >208 ( Figure 1 ) and the rates of definite/probable ST and all-cause death ( Figure 2 ) increased progressively with HbA1c groups in a stepwise fashion, whereas the rates of cardiac death and MI were elevated in patients with intermediate (compared to low) HbA1c levels but did not increase further with HbA1c levels >8.5% ( Figure 2 ). Clinically relevant bleeding was most frequent in the intermediate HbA1c group (13.1%) compared with the low (8.2%) and high (9.5%) HbA1c groups (p = 0.04, Figure 3 ). The proportion of patients with ARU ≥550 was not associated with HbA1c levels (4.2% vs 3.4% vs 4.1%; p = 0.79).

In a model adjusted for PRU, HbA1c >8.5% remained associated with definite/probable ST (HR 3.92, 95% CI 1.24 to 12.37, p = 0.02). Furthermore, HbA1c >8.5% was significantly associated with all-cause death and cardiac death in the fully adjusted analysis, whereas PRU >208 was not ( Table 3 ).

| Adjusted for PRU Only | Fully Adjusted ∗ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (Confidence Interval) | P value | Hazard Ratio (Confidence Interval) | P value | |

| Stent thrombosis † | ||||

| HbA1c high vs low | 3.92 (1.24-12.37) | 0.02 | . | |

| HbA1c mid vs low | 2.38 (0.82-6.92) | 0.11 | . | |

| PRU >208 | 1.94 (0.79-4.77) | 0.15 | . | |

| Major adverse cardiac events ‡ | ||||

| HbA1c high vs low | 1.77 (0.98-3.17) | 0.057 | 1.54 (0.86-2.77) | 0.15 |

| HbA1c mid vs low | 2.04 (1.31-3.16) | 0.002 | 1.81 (1.16-2.82) | 0.009 |

| PRU >208 | 1.04 (0.76-1.43) | 0.79 | 1.06 (0.77-1.45) | 0.73 |

| Death § | ||||

| HbA1c high vs low | 2.03 (0.93-4.40) | 0.07 | 2.42 (1.08-5.41) | 0.03 |

| HbA1c mid vs low | 2.05 (1.10-3.83) | 0.02 | 1.69 (0.89-3.22) | 0.11 |

| PRU >208 | 1.81 (1.03-3.20) | 0.04 | 1.56 (0.87-2.77) | 0.13 |

| Cardiac death ¶ | ||||

| HbA1c high vs low | 2.95 (1.03-8.48) | 0.04 | 4.24 (1.41-12.70) | 0.01 |

| HbA1c mid vs low | 3.61 (1.52-8.55) | 0.004 | 3.23 (1.34-7.81) | 0.009 |

| PRU >208 | 1.81 (0.89-3.67) | 0.10 | 1.12 (0.53-2.36) | 0.76 |

| Myocardial infarction ‖ | ||||

| HbA1c high vs low | 2.76 (1.14-6.66) | 0.02 | 2.34 (0.97-5.64) | 0.059 |

| HbA1c mid vs low | 2.97 (1.48-5.96) | 0.002 | 2.58 (1.28-5.22) | 0.008 |

| PRU >208 | 1.14 (0.72-1.80) | 0.58 | 1.08 (0.68-1.72) | 0.76 |

| Bleeding ∗∗ | ||||

| HbA1c High v Low | 1.21 (0.67-2.19) | 0.53 | 1.22 (0.67-2.24) | 0.52 |

| HbA1c Mid v Low | 1.72 (1.15-2.58) | 0.009 | 1.40 (0.93-2.11) | 0.11 |

| PRU > 208 | 0.89 (0.61-1.30) | 0.54 | 0.76 (0.52-1.12) | 0.16 |

∗ Adjusted models selected with a stepwise selection process with entry and exit criteria both = 0.1—HbA1c category and PRU >208 were kept in every model; candidate variables were: men, Caucasian, creatinine clearance <60 ml/min, current smoker, acute coronary syndromes, previous myocardial infarction, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, baseline hemoglobin, baseline white blood cell count, baseline platelet count, history of peripheral arterial disease, history of congestive heart failure, degree of coronary artery >1, Killip’s class II to IV at the time of percutaneous coronary intervention, age, and body mass index.

† Number of stent thrombosis events (23) was insufficient for multivariate adjustment.

‡ Selected covariates: HbA1c category, PRU >208, creatinine clearance <60 ml/min, previous myocardial infarction, a history of peripheral arterial disease, a history of congestive heart failure, baseline platelet count, and degree of coronary artery >1.

§ Selected covariates: HbA1c category, PRU >208, age, previous myocardial infarction, hyperlipidemia, baseline white blood cell count, the history of peripheral arterial disease, the history of congestive heart failure, and degree of coronary artery >1.

¶ Selected covariates: HbA1c category, PRU >208, age, body mass index, men, previous myocardial infarction, hyperlipidemia, baseline hemoglobin, and baseline white blood cell count.

‖ Selected covariates: HbA1c category, PRU >208, previous myocardial infarction, baseline hemoglobin, baseline platelet count, the history of peripheral arterial disease, and degree of coronary artery >1.

∗∗ Selected covariates: HbA1c category, PRU >208, age, acute coronary syndromes, baseline hemoglobin, the history of peripheral arterial disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree