Chapter 1 History of Surgery

Importance of Understanding Surgical History

Historical Relationship Between Surgery and Medicine

Knowledge of Human Anatomy

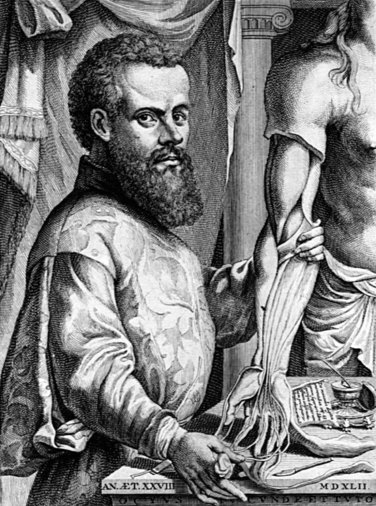

Few individuals have had an influence on the history of surgery as overwhelmingly as that of the Brussels-born Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564; Fig. 1-1). As professor of anatomy and surgery in Padua, Italy, Vesalius taught that human anatomy could be learned only through the study of structures revealed by human dissection. In particular, his great anatomic treatise, De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem (1543), provided fuller and more detailed descriptions of human anatomy than any of his illustrious predecessors. Most importantly, Vesalius corrected errors in traditional anatomic teachings propagated 13 centuries earlier by Greek and Roman authorities, whose findings were based on animal rather than human dissection. Even more radical was Vesalius’ blunt assertion that anatomic dissection must be completed by physician-surgeons themselves—a direct renunciation of the long-standing doctrine that dissection was a grisly and loathsome task to be performed by a diener-like individual while the perched physician-surgeon lectured by reading from an orthodox anatomic text from on high. This principle of hands-on education would remain Vesalius’ most important and long-lasting contribution to the teaching of anatomy. Vesalius’ Latin literae scriptae ensured its accessibility to the most well-known physicians and scientists of the day. Latin was the language of the intelligentsia and the Fabrica became instantly popular, so it was only natural that over the next 2 centuries, the work would go through numerous adaptations, editions, and revisions, although always remaining an authoritative anatomic text.

Method of Controlling Hemorrhage

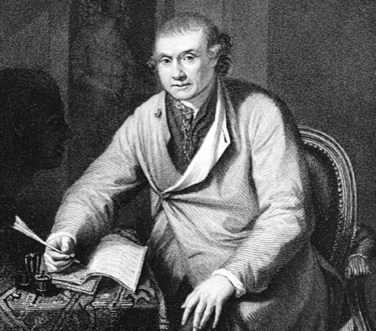

The position of Ambroise Paré (1510-1590) in the evolution of surgery remains of supreme importance (Fig. 1-2). He played the major role in reinvigorating and updating Renaissance surgery and represents severing of the final link between surgical thought and techniques of the ancients and the push toward more modern eras. From 1536 until just before his death, Paré was engaged as an army surgeon, during which time he accompanied different French armies on their military expeditions, or was performing surgery in civilian practice in Paris. Although other surgeons made similar observations about the difficulties and nonsensical aspects of using boiling oil as a means of cauterizing fresh gunshot wounds, Paré’s use of a less irritating emollient of egg yolk, rose oil, and turpentine brought him lasting fame and glory. His ability to articulate such a finding in a number of textbooks, all written in the vernacular, allowed his writings to reach more than just the educated elite. Among Paré’s important corollary observations was that when performing an amputation, it was more efficacious to ligate individual blood vessels than to attempt to control hemorrhage by means of mass ligation of tissue or with hot oleum. Described in his Dix Livres de la Chirurgie avec le Magasin des Instruments Necessaires à Icelle (1564), the free or cut end of a blood vessel was doubly ligated and the ligature was allowed to remain undisturbed in situ until, as a result of local suppuration, it was cast off. Paré humbly attributed his success with patients to God, as noted in his famous motto, “Je le pansay. Dieu le guérit,”—that is, “I treated him. God cured him.”

Pathophysiologic Basis of Surgical Diseases

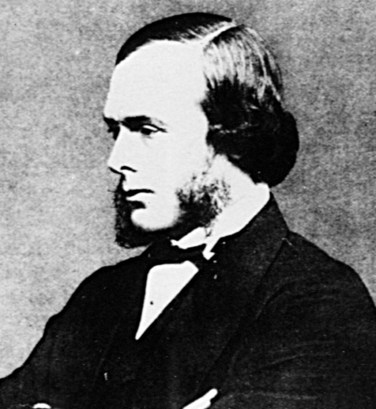

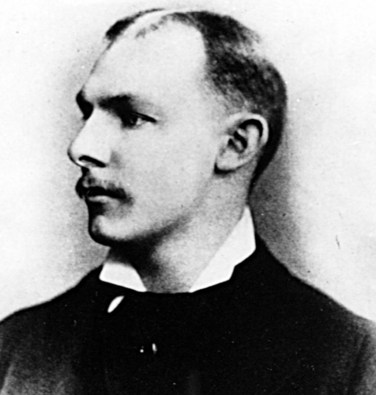

Although it would be another 3 centuries before the third desideratum, that of anesthesia, was discovered, much of the scientific understanding concerning efforts to relieve discomfort secondary to surgical operations was based on the 18th century work of England’s premier surgical scientist, John Hunter (1728-1793; Fig. 1-3). Considered one of the most influential surgeons of all time, his endeavors stand out because of the prolificacy of his written word and the quality of his research, especially in using experimental animal surgery as a way to understand the pathophysiologic basis of surgical diseases. Most impressively, Hunter relied little on the theories of past authorities but rather on personal observations, with his fundamental pathologic studies first described in the renowned textbook A Treatise on the Blood, Inflammation, and Gun-Shot Wounds (1794). Ultimately, his voluminous research and clinical work resulted in a collection of more than 13,000 specimens, which became one of his most important legacies to the world of surgery. It represented a unique warehousing of separate organ systems, with comparisons of these systems—from the simplest animal or plant to humans—demonstrating the interaction of structure and function. For decades, Hunter’s collection, housed in England’s Royal College of Surgeons, remained the outstanding museum of comparative anatomy and pathology in the world, until a World War II Nazi bombing attack of London created a conflagration that destroyed most of Hunter’s assemblage.

Anesthesia

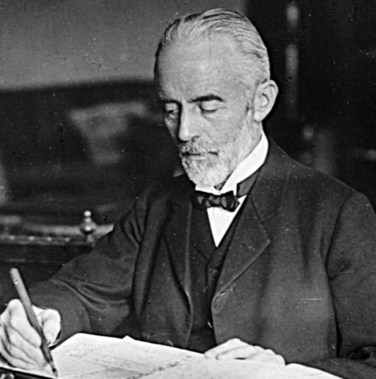

Still, by the mid-19th century, both physicians and patients were coming to hold surgery in relatively high regard for its pragmatic appeal, technologic virtuosity, and unambiguously measurable results. After all, surgery appeared a mystical craft to some. To be allowed to consensually cut into another human’s body, to gaze at the depth of that person’s suffering, and to excise the demon of disease seemed an awesome responsibility. It was this very mysticism, however, long associated with religious overtones, that so fascinated the public and their own feared but inevitable date with a surgeon’s knife. Surgeons had finally begun to view themselves as combining art and nature, essentially assisting nature in its continual process of destruction and rebuilding. This regard for the natural would spring from the eventual, although preternaturally slow, understanding and use of Joseph Lister’s (1827-1912) techniques (Fig. 1-4).

Early 20th Century

With all four fundamental clinical prerequisites in place by the turn of the century, highlighted by the emerging clinical triumphs of various English surgeons, including Robert Tait (1845-1899), William Macewen (1848-1924), and Frederick Treves (1853-1923); German-speaking surgeons, including Theodor Billroth (1829-1894; Fig. 1-5), Theodor Kocher (1841-1917; Fig. 1-6), Friedrich Trendelenburg (1844-1924), and Johann von Mikulicz-Radecki (1850-1905); French surgeons, including Jules Peán (1830-1898), Just Lucas-Championière (1843-1913), and Marin-Theodore Tuffiér (1857-1929); Italian surgeons, most notably Eduardo Bassini (1844-1924) and Antonio Ceci (1852-1920); and several American surgeons, exemplified by William Williams Keen (1837-1932), Nicholas Senn (1844-1908), and John Benjamin Murphy (1857-1916), scalpel wielders had essentially explored all cavities of the human body. Nonetheless, surgeons retained a lingering sense of professional and social discomfort and continued to be pejoratively described by nouveau scientific physicians as nonthinkers who worked in little more than an inferior and crude manual craft.

Ascent of Scientific Surgery

William Stewart Halsted (1852-1922), more than any other surgeon, set the scientific tone for this most important period in surgical history (Fig. 1-7). He moved surgery from the melodramatics of the 19th-century operating theater to the starkness and sterility of the modern operating room, commingled with the privacy and soberness of the research laboratory. As professor of surgery at the newly opened Johns Hopkins Hospital and School of Medicine, Halsted proved to be a complex personality, but the impact of this aloof and reticent man would become widespread. He introduced a new surgery and showed that research based on anatomic, pathologic, and physiologic principles and the use of animal experimentation made it possible to develop sophisticated operative procedures and perform them clinically with outstanding results. Halsted proved, to an often leery profession and public, that an unambiguous sequence could be constructed from the laboratory of basic surgical research to the clinical operating room. Most importantly, for surgery’s own self-respect, he demonstrated during this turn of the century renaissance in medical education that departments of surgery could command a faculty whose stature was equal in importance and prestige to that of other more academic or research-oriented fields, such as anatomy, bacteriology, biochemistry, internal medicine, pathology, and physiology.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree