Chapter 71 Gynecologic Surgery

Pelvic Embryology And Anatomy

Embryology

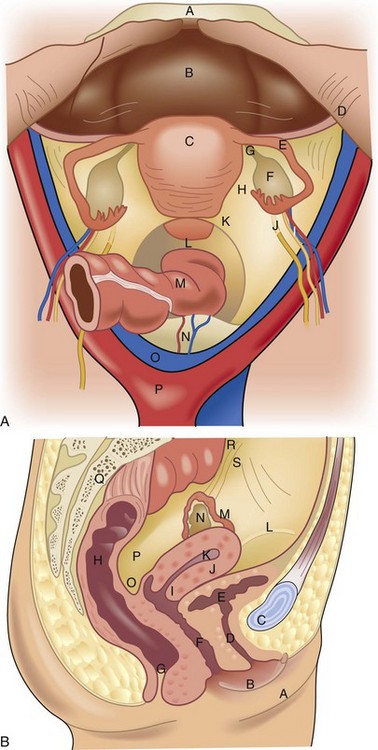

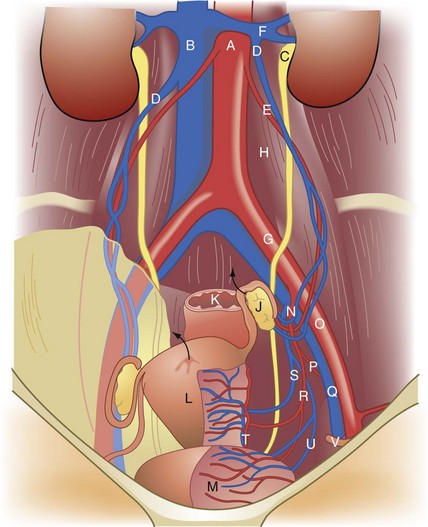

The internal genitalia are derived from the genital ridge. The ovaries develop from the incorporation of primordial germ cells into coelomic epithelium of the mesonephric (wolffian) duct and the tubes, uterus, cervix, and upper two thirds of the vagina develop from the paramesonephric (mullerian) duct. The embryologic ovaries migrate caudad to the true pelvis. Primordial ovarian follicles develop but remain dormant until stimulation in adolescence by gonadotropins. The paired mullerian ducts migrate caudad and medially to form the fallopian tubes and fuse in the midline to form the uterus, cervix, and upper vagina. The wolffian ducts regress. Failure or partial failure of these processes can result in distortions of anatomy and potential diagnostic dilemmas (Table 71-1).

Table 71-1 Selected Anatomic Abnormalities as a Result of Disrupted Embryogenesis

| ORGAN | ABNORMALITY |

|---|---|

| Ovary | Duplication of ovary; secondary ovarian rests; paraovarian cysts (wolffian remnants) |

| Tube | Congenital absence; paratubal cyst (hydatid of Morgagni) |

| Uterus | Agenesis; complete or partial duplication of the uterine fundus |

| Cervix | Agenesis; complete or partial duplication of the cervix |

| Vagina | Agenesis; transverse or longitudinal septum; paravaginal (Gartner’s duct) cyst |

| Vulva | Fusion; hermaphroditism; cyst of the canal of Nuck (round ligament cyst) |

Anatomy

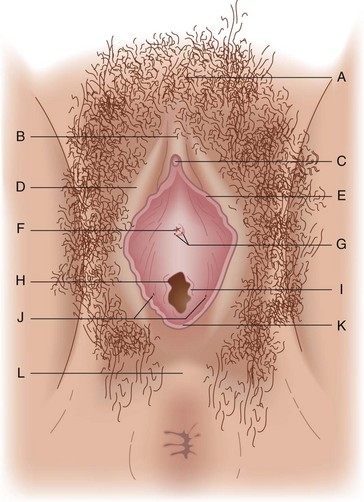

External Genitalia

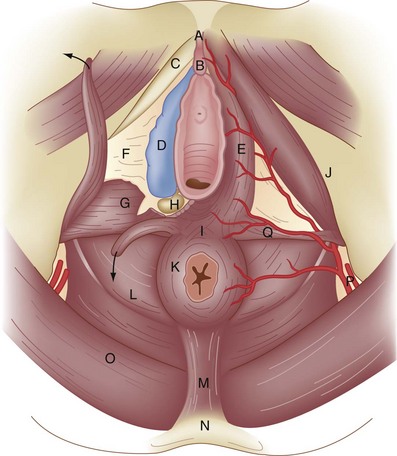

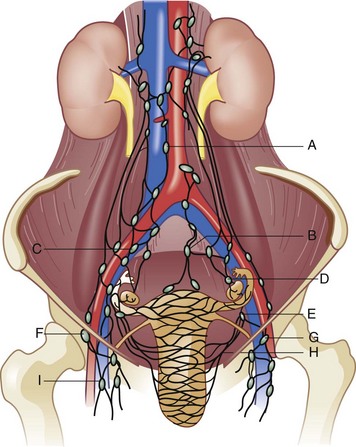

The external genitalia consist of the mons veneris, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, vulvar vestibule, urethral meatus, and ostia of the accessory glandular structures (Fig. 71-1). These structures overlie the fascial and muscle layers of the perineum. The perineum is the most caudal region of the trunk; it includes the pelvic floor and those structures occupying the pelvic outlet. It is bounded superiorly by the funnel-shaped pelvic diaphragm and inferiorly by the skin covering the external genitalia, anus, and adjacent structures. Laterally, the perineum is bounded by the medial surface of the inferior pubic rami, obturator internus muscle below the origin of the levator ani muscle, coccygeus muscle, medial surface of the sacrotuberous ligaments, and overlapping margins of the gluteus maximus muscles (Fig. 71-2).

Reproductive Physiology

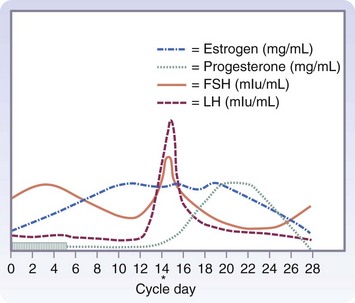

The development of a differential diagnosis of gynecologic complaints is facilitated by an understanding of the reproductive cycle and eliciting a careful menstrual history. Many conditions are a direct consequence of aberrations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian cycle and the effects of the hormonal milieu on the endometrium. Others tend to be mere variations in the presentation of different phases of the cycle. A detailed description of the cycle is beyond our scope here, but the surgeon needs to have a basic understanding of the relationships in this complex process to elicit an adequate history, interpret the findings on physical examination, use ancillary tests appropriately, and formulate the differential diagnosis (Fig. 71-6).

Clinical Evaluation

Diagnostic Considerations

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree