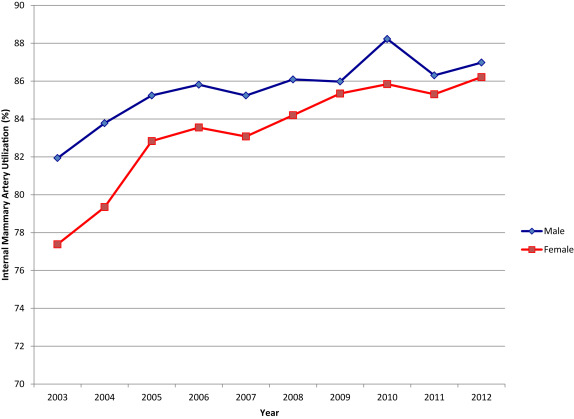

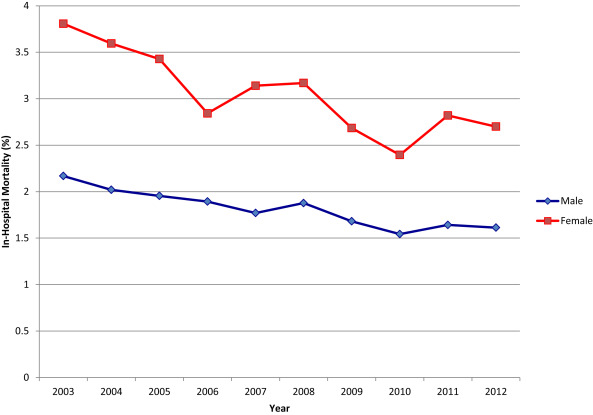

Women historically have a greater risk of operative mortality than men after coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). There is paucity of contemporary data in gender outcomes of surgical revascularization and understanding modifiable factors that contribute to gender differences are critical for quality improvement and practice change. We, therefore, sought to examine whether the gender gap in CABG outcomes is closing in the contemporary era by conducting a retrospective analysis from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database from 2003 to 2012. We included all patients who underwent isolated CABG surgery (n = 2,272,998; female n = 623,423 [27.4%]; male n = 1,649,575 [72.6%]). The annual rate of CABG surgeries decreased by 53.7% in men and 57.8% in women over the 10-year study period. Although internal mammary artery use in women was less frequent than in men in 2003 (77.4% vs 81.9%, p <0.001), a significant uptrend closed this gap by 2012 (86.2% vs 87.0%, p trend 0.003). Overall, unadjusted in-hospital mortality was greater in women (3.2% vs 1.8%, p <0.001). Female gender remained an independent predictor of mortality after multivariate adjustment (odds ratio 1.40, 95% CI 1.36 to 1.43, p <0.001) across all age groups. However, in-hospital mortality decreased at a faster rate in women (3.8% to 2.7%, RR −29.1%, p trend 0.002) than in men (2.2% to 1.6%, RR −25.7%, p trend <0.001) from 2003 to 2012. In conclusion, CABG rates in the United States are decreasing over time, yet in-hospital mortality continues to improve. Women have worse in-hospital outcomes than men; however, the gender gap is slowly closing.

Gender differences in clinical presentation of coronary artery disease (CAD) and outcomes after acute coronary syndrome have been well established. The onset of clinical symptoms related to CAD is at least a decade later in women. The atypical nature of symptoms and lower diagnostic accuracy of noninvasive testing in women make prompt diagnosis and treatment challenging. There have only been minor differences in clinical outcomes after stent-based revascularization between men and women, whereas gender-based differences in outcomes have historically been more prominent in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Women have had more co-morbidities, worse postoperative outcomes, fewer bypass grafts, and a lower frequency of internal mammary artery (IMA) utilization. In addition, women undergoing CABG had longer hospitalizations and subsequent higher cost of care. There are limited data regarding gender differences in outcomes after CABG in the contemporary era. Using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database, we examined CABG gender trends from 2003 to 2012 with respect to in-hospital outcomes, including mortality, stroke, bleeding, respiratory failure, acute renal failure (ARF), cardiogenic shock, wound infection, and sepsis. We hypothesized that the gender gap with respect to CABG outcomes is closing over time but that women still have worse postoperative outcomes. Understanding modifiable factors that contribute to these gender differences is critical for quality improvement and future practice change.

Methods

Data were obtained from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project—NIS files from 2003 to 2012. The NIS is a 20% stratified sample of all nonfederal US hospitals and in 2012 contained deidentified information on 36,484,846 discharges from 4,378 hospitals and 44 states. Discharges are weighted based on the sampling scheme to permit inferences for a nationally representative population. Each record in the NIS includes all procedure and diagnosis International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes recorded for each patient’s hospital discharge.

From January 2003 to December 2012, hospitalizations leading to isolated CABG surgery were selected by searching for the ICD-9-Clinical Modification (CM) procedure codes 36.10, 36.11, 36.13, 36.14, 36.15, 36.16, 36.17, or 36.19 in any of the 15 procedure fields in the database. Patients aged <18 years were excluded from analyses. Concomitant valve surgeries were excluded. The absence of ICD-9-CM codes 39.61 and 39.62 identified off-pump CABG surgery.

Patient-level and hospital-level variables were included as baseline characteristics. Hospital-level data elements were derived from the American Heart Association Annual Survey Database. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality co-morbidity measures based on the Elixhauser methods were used to identify co-morbid conditions. The primary outcome measures were in-hospital all-cause mortality, stroke, bleeding, respiratory failure and ARF. Other outcome measures assessed included cardiogenic shock, wound infection, and sepsis. Outcome measures were identified by the following ICD-9 codes: stroke (997.02, 362.31, 368.12, 781.4, 433.11, 435, 434), major bleeding (430 to 432, 578.X, 719.1X, 423.0, 599.7, 626.2, 626.6, 626.8, 627.0, 627.1, 786.3, 784.7, and 459.0), respiratory failure (518.81, 518.84, and 799.1), ARF (584), cardiogenic shock (785.51), wound infection (998.51 and 998.59), and sepsis (038, 995.91, 995.92 and 999.3).

We calculated procedure rates as the weighted number of CABG procedures divided by 20% of the total number of US adults during the same periods. Estimates of the US adult population from 2003 to 2012 were obtained from the US Census Bureau. Trends in the annual rates of CABG, IMA utilization, and in-hospital mortality were assessed using time series modeling and stratified by gender. To compare baseline characteristics and in-hospital clinical outcomes with respect to gender, either the Mann–Whitney Wilcoxon nonparametric tests or Student t test were used for continuous variables, and Pearson chi-square tests were used for categorical variables. Continuous variables are presented as medians; categorical variables are expressed as frequencies (percentages).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to adjust for baseline differences between male and female groups by adjusting for univariate predictors of examined outcomes (p <0.01). The models were adjusted for the following demographic, hospital-level, and procedural variables: age, race, hospital bedsize, hospital teaching status, region, payer, anemia, collagen vascular disease, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, coagulopathy, hypertension, liver disease, neurological disorders, obesity, peripheral vascular disorders, chronic renal failure, hemodialysis dependence, valve disease, IMA use, number of bypass grafts, previous CABG and previous percutaneous coronary intervention. For all regression analyses, the Taylor linearization method “with replacement” design was used to compute variances. Similar analyses were performed for various age groups within female gender (<50, 50 to 59, 60 to 69, 70 to 79, and >80 years).

All statistical tests were 2-sided, and a p value of <0.05 was set a priori to be statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and SPSS, version 20 (IBM corporation, Armonk, New York).

Results

Of the 2,272,998 discharge records analyzed from patients who underwent CABG without concomitant valve surgery from 2003 to 2012, 27.4% (n = 623,423) were women and the remaining 72.6% (n = 1,649,575) were men. Overall baseline and hospital characteristics of the study groups divided by gender are presented in Table 1 . Women were older than men in undergoing CABG and had greater number of co-morbidities including hypertension, diabetes, anemia, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, obesity, peripheral vascular disease, and chronic renal failure. Although there was an increasing frequency of reported co-morbidities over time, similar gender differences were found when patient risk profiles were compared for each year across the 10-year study period ( Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 ).

| Characteristics | Male (N=1,649,575) | Female (N=623,423) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD (years) | 65.0 ± 10.6 | 66.9 ± 11.0 | <0.001 |

| Elective Admission | 47.1% | 43.0% | <0.001 |

| White race | 81.4% | 76.5% | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 71.4% | 74.1% | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, uncomplicated | 30.3% | 35.2% | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus with chronic complications | 5.5% | 7.9% | <0.001 |

| Anemia ∗ | 14.3% | 18.3% | <0.001 |

| Collagen Vascular Disease | 1.1% | 2.8% | <0.001 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 0.8% | 1.4% | <0.001 |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 21.0% | 24.1% | <0.001 |

| Coagulopathy | 9.9% | 10.7% | <0.001 |

| Liver Disease | 1.0% | 0.8% | <0.001 |

| Neurological Disorder | 2.5% | 3.1% | <0.001 |

| Obesity † | 13.6% | 19.4% | <0.001 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 12.7% | 14.8% | <0.001 |

| Previous Percutaneous Coronary Intervention | 11.8% | 9.8% | <0.001 |

| Previous Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting | 1.4% | 1.1% | <0.001 |

| Internal Mammary Artery used | 85.9% | 82.8% | <0.001 |

| Bilateral Internal Mammary Artery used | 4.1% | 2.4% | <0.001 |

| On Pum | 74.9% | 72.2% | <0.001 |

| Number of Grafts | |||

| 1 | 13.9% | 18.7% | <0.001 |

| 2 | 34.2% | 37.7% | <0.001 |

| 3 | 32.1% | 27.5% | <0.001 |

| 4 | 16.2% | 10.8% | <0.001 |

| Payer | <0.001 | ||

| Medicare | 48.8% | 60.7% | |

| Medicaid | 4.5% | 7.0% | |

| Private | 39.4% | 26.3% | |

| Uninsured | 3.8% | 3.5% | |

| Hospital Teaching Status | <0.001 | ||

| Teaching | 57.7% | 57.8% | |

| Hospital Bed Size | 0.003 | ||

| Small | 6.5% | 6.7% | |

| Medium | 19.2% | 19.2% | |

| Large | 74.3% | 74.2% | |

| Hospital Region | <0.001 | ||

| Northeast | 16.2% | 15.9% | |

| Midwest | 24.1% | 25.0% | |

| South | 43.2% | 44.6% | |

| West | 16.6% | 14.6% | |

| Length of Stay (Days) | <0.001 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 9.0 ± 7.2 | 10.4 ± 8.3 | |

| Median | 7 | 8 | |

| Cost (US Dollars) | <0.001 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 113,595.3 ± 92,748.7 | 121,499.1 ± 100,213.6 | |

| Median | 87,919.0 | 93,429.0 | |

∗ Anemia as reported by ICD-10 codes: D501, D508, D509, D510, D511, D512, D513, D518, D519, D520, D521, D528, D529, D530, D531, D532, D538, D539, D630, D631, D638, D649.

† Obesity as reported by ICD-10 codes: E6601, E6609, E661, E662, E668, E669, O99210, O99211, O99212, O99213, O99214, O99215, R939, Z6830, Z6831, Z6832, Z6833, Z6834, Z6835, Z6836, Z6837, Z6838, Z6839, Z6841, Z6842, Z6843, Z6844, Z6845, Z6854.

Payer mix varied greatly by gender, with Medicare and Medicaid insurances being more common in women versus men, whereas private insurance covered 39.4% of men and only 26.3% of women. Hospital teaching status, bedsize, and region were numerically similar between genders. Median length of stay was one day longer for women and mean cost of hospitalization was also higher for women ( Table 1 ).

The annual rate of CABG surgeries decreased by 53.7% in men over the study period from 4,408 procedures per million adults per year in 2003 to 2,042 procedures per million adults per year in 2012. Similarly, there was a 57.8% reduction in the annual rate of CABG surgeries in women from 1,479 procedures per million adults per year in 2003 to 639 procedure in 2012.

Men had a higher rate of triple or quadruple bypass graft utilization compared with women who were more likely to have only 1 or 2 grafts ( Table 1 ). Overall, the IMA was used less frequently in women (82.8% vs 85.9%, p <0.001). Although IMA use in women was less than men in 2003 (77.4% vs 81.9%, p <0.001), a significant uptrend closed this gap by 2012 (86.2% vs 87.0%, p trend = 0.003; Figure 1 ).

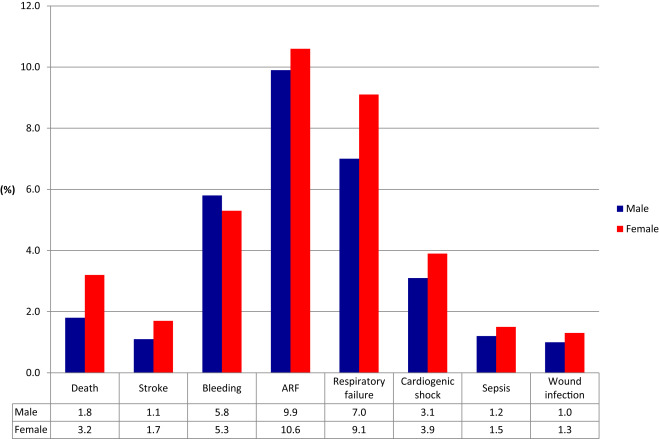

Figure 2 depicts the unadjusted primary and secondary in-hospital outcomes by gender for the entire study period. All in-hospital clinical outcomes, except bleeding, were significantly higher in women. In-hospital mortality was 3.2% in women versus 1.8% in men (p <0.001). Table 2 lists the unadjusted ORs for the association between female gender and clinical outcomes. Women had a 72% increased risk of mortality (OR 1.72, 95% CI 1.69 to 1.75) and 49% increased risk of stroke (OR 1.49, 95% CI 1.46 to 1.53) compared with men. Other clinical outcomes including ARF, respiratory failure, cardiogenic shock, sepsis, and wound infection carried a ∼10% to 30% increased risk in women ( Table 2 , p <0.001 for all).

| Outcome | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P-Value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 1.72 (1.69-1.75) | <0.001 | 1.40 (1.36-1.43) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 1.49 (1.46-1.53) | <0.001 | 1.35 (1.31-1.40) | <0.001 |

| Bleeding | 0.90 (0.89-0.91) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.82-0.84) | <0.001 |

| Acute Renal Failure | 1.08 (1.07-1.09) | <0.001 | 0.89 (0.88-0.91) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory Failure | 1.32 (1.30-1.33) | <0.001 | 1.21 (1.20-1.23) | <0.001 |

| Cardiogenic Shock | 1.24 (1.23-1.26) | <0.001 | 1.13 (1.10-1.15) | <0.001 |

| Sepsis | 1.19 (1.16-1.22) | <0.001 | 1.02 (0.99-1.06) | 0.16 |

| Wound Infection | 1.29 (1.25-1.32) | <0.001 | 1.15 (1.11-1.18) | <0.001 |

Although CABG mortality was higher in women for each year of the study period, Figure 3 demonstrates a steady closing of the gender gap with decreasing in-hospital mortality from 2003 to 2012 in both men and women (p trend <0.001 in men and 0.002 in women) with a faster rate of decrease in women. There was a 25.7% relative risk reduction in in-hospital mortality in men (from 2.2% in 2003 to 1.6% in 2012) and a 29.1% relative risk reduction in women (from 3.8% in 2003 to 2.7% in 2012; Figure 3 ).

After multivariate adjustment, the odds of death and stroke in women were attenuated but remained significantly higher with a 40% increased risk of death (OR 1.40, 95% CI 1.36 to 1.43) and 35% increased risk of stroke (OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.31 to 1.40). The ORs of respiratory failure, cardiogenic shock, and wound infection in women were similarly attenuated to ∼15% to 20% increased risk, but remained statistically significant ( Table 2 ). Only sepsis risk became neutralized between men and women after adjustment (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.06). Bleeding rate remained lower in women (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.82 to 0.84).

Table 3 lists independent predictors of in-hospital mortality after CABG after adjusting for baseline characteristics. Of the variables included in the model, congestive heart failure was the strongest predictor of death with a fourfold increased risk, while having liver disease, coagulopathy, and being dialysis dependent doubled mortality risk. Female gender remained a strong independent predictor of mortality in our adjusted model with a 40% increased risk ( Table 3 ). When stratified by gender, liver disease, coagulopathy, pulmonary circulation disorders, and peripheral vascular disease were stronger predictors of in-hospital mortality in women, whereas congestive heart failure and dialysis were stronger predictors in men. Previous CABG was only a predictor of mortality in men. The increased mortality risk for women was found to be similarly high, ranging from ∼30% to 45% increased risk, across all age groups ( Table 4 ).