INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

In 1991, the National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference established the current indications for bariatric surgery, which have remained in effect since that time. These guidelines recommend bariatric surgery for patients

with acceptable operative risks

with acceptable operative risks

who are well informed and motivated

who are well informed and motivated

evaluated by a multidisciplinary team

evaluated by a multidisciplinary team

with failure of established weight control programs

with failure of established weight control programs

with body mass index (BMI) ≥40, or ≥35 with at least one high risk, obesity-related comorbid condition

with body mass index (BMI) ≥40, or ≥35 with at least one high risk, obesity-related comorbid condition

The prominent obesity-related comorbid conditions include hypertension, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea, cardiomyopathy, and pseudotumor cerebri.1,2 Other common obesity-related comorbidities include gastroesophageal reflux, osteoarthritis, infertility, cholelithiasis, venous stasis, and urinary stress incontinence.3 With a large body of evidence supporting the efficacy of bariatric surgery in ameliorating the above comorbidities, debate over the role of bariatric surgery specifically to treat these conditions, more than the obesity, has begun.4,5

Relative contraindications to bariatric surgery include the following.

Alcohol or drug dependence

Alcohol or drug dependence

Ongoing smoking

Ongoing smoking

Uncontrolled psychiatric disorders such as depression or schizophrenia

Uncontrolled psychiatric disorders such as depression or schizophrenia

Inability to comprehend the requirements for postoperative nutritional and behavioral changes

Inability to comprehend the requirements for postoperative nutritional and behavioral changes

Unacceptable cardiorespiratory risk (American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] class IV)

Unacceptable cardiorespiratory risk (American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] class IV)

End-stage hepatic disease

End-stage hepatic disease

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Patients preparing for gastric bypass require both preoperative medical evaluation and optimization of medical comorbidities prior to surgery. Medical clearance requires a comprehensive and thorough review of the patient’s medical history, specifically looking for factors which can predict an adverse outcome. Independent predictors of surgical morbidity and mortality include age ≥45 years, male gender, BMI ≥50 kg/m2, risk for pulmonary embolism, and hypertension.6,7 Collectively, these clinical findings can be used to calculate an Obesity Surgery Mortality Risk Score (OS-MRS), which has been validated at multiple institutions. Patients with 0 or 1 comorbidity are considered low risk or class A with a 0.2% risk of mortality. Those in class B have 2 or 3 comorbidities and are at intermediate risk of 1.2%. Class C patients are highest risk and have 4 or 5 comorbidities with a corresponding mortality of 2.4%.6 BMI ≥50 kg/m2 and cigarette smoking have also been shown to be associated with higher postoperative surgical morbidities.8,9 Preoperative workup should include the following:

Comprehensive history and physical examination

Comprehensive history and physical examination

12-lead EKG

12-lead EKG

Basic blood chemistries, lipid profile, and nutritional panel

Basic blood chemistries, lipid profile, and nutritional panel

Chest radiograph

Chest radiograph

The choice of operation for a particular patient must take into account several issues including the surgeon’s expertise and the patient’s preference, BMI, metabolic conditions, and other associated comorbidities. While gastric bypass is largely considered the most effective procedure in achieving long-term weight loss, it is also the most effective in reducing the metabolic derangements of obesity, including diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. However, these benefits come with a slightly higher overall mortality rate. For gastric bypass, an average 30-day mortality is 0.16% compared with that of laparoscopic adjustable gastric band placement at 0.06%.10 For this reason, high-risk patients may at times be counseled away from the more definitive gastric bypass and toward the safer, albeit less effective, laparoscopic gastric banding.

The benefit of preoperative weight loss prior to gastric bypass has been debated. A recent randomized trial demonstrated that patients who achieve ≥5% excess body weight loss prior to surgery had significantly lower weight and BMI and a higher excess body weight loss 1 year after surgery.11 The success of this and other trials is felt to predict those patients with the discipline and willingness to follow healthy lifestyles that will ultimately translate to successful and sustained long-term weight loss.12 As a result, many surgeons will place patients on one of many available forms of preoperative weight loss diet for 2 to 4 weeks prior to surgery, with a goal of 10% excess body weight loss. Many forms of commercial dietary programs are available for these purposes, often consisting of a high-protein, low-fat, low-carbohydrate, predominately liquid diet. An additional benefit of this preoperative liquid diet is decreased liver size and density that makes manipulation of the left lobe of the liver easier during surgery.

SURGERY

SURGERY

All patients should receive routine deep venous thrombosis (DVT) chemoprophylaxis immediately prior to arrival in the operating room, as initial development of DVT is felt to occur intraoperatively in this high-risk population. In addition, routine preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis is also indicated. A second generation cephalosporin is adequate, but typically requires increased dosing in morbidly obese patients.

Patient Positioning

Patient positioning is often dictated by the surgeon’s preference. Some surgeons prefer the French or lithotomy position. The main advantage of this position is access in between the patient’s legs and the inline trajectory of one’s laparoscopic instruments. This centers the surgeon over the operative field and improves the posture while minimizing shoulder fatigue. However, this position can be difficult and time consuming and places patients at risk for nerve injury if not positioned properly. Most surgeons have evolved their procedure to a completely supine position with arms outstretched on and secured to arm boards. A footboard is recommended to minimize patient slippage inferiorly during reverse Trendelenburg positioning, as is an upper thigh strap to minimize lateral slippage during rotation of the patient. All bolsters placed behind the patient’s neck and/or shoulders during anesthesia to facilitate endotracheal intubation should be removed prior to initiation of surgery. A Foley catheter is optional. Routine cardiac noninvasive monitoring is essential. Invasive monitoring, including arterial and central venous catheters, is not routinely indicated and is only utilized in selected cases where such additional monitoring is necessary.

Technique

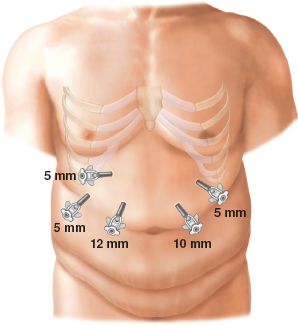

Standard technique includes a 5-trocar configuration (Fig. 9.1). Initial cannulation of the abdominal cavity with a Veress needle is typically through the camera port, located in the left supraumbilical region. Upon insufflation to 15 mm Hg, the Veress needle is removed and a 12-mm trocar is inserted followed by camera confirmation of no visceral injury from entry. Subsequent 5-mm trocars are placed in the far left and right subcostal margins just above the viscera, along with a right epigastric (12-mm) and right upper quadrant (5-mm) trocars. The far right subcostal trocar secures a serpentine liver retractor for anterior retraction of the left lobe of the liver. Alternatively, the subxiphoid 5-mm trocar site can be used to accommodate a Nathanson liver retractor. The operating surgeon utilizes the epigastric and right upper quadrant trocars while the assistant utilizes the left subcostal trocar and the laparoscope.

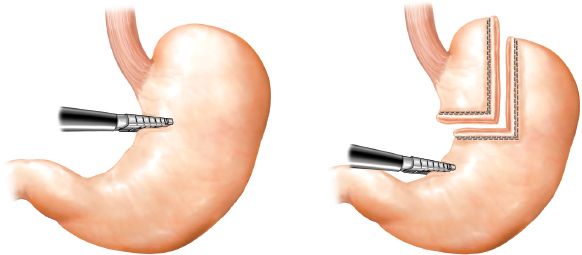

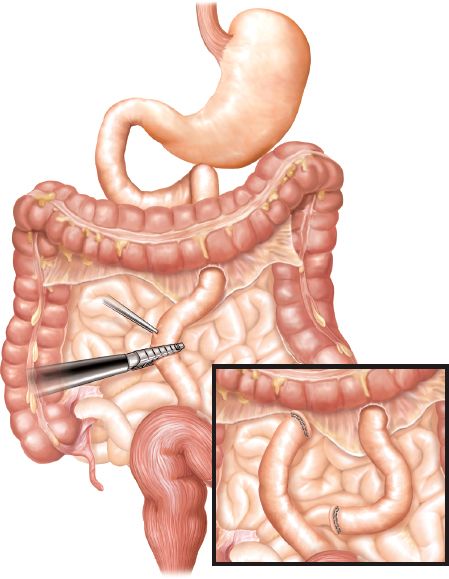

Creation of the gastric pouch and gastrojejunostomy begins with division of the gastrohepatic ligament (Fig. 9.2). The vasculature of the lesser curve of the stomach should be divided with a vascular stapler. Creation of the gastric pouch then proceeds with transverse division of the proximal stomach approximately 4 cm distal to the gastroesophageal junction. The transection is made approximately 3 cm wide and then proceeds superiorly toward the lateral aspect of the angle of His. Once the pouch is constructed, the gastrojejunostomy can be formed. The small bowel and its mesentery are divided approximately 30 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz, and the distal (Roux) limb is brought up to the gastric pouch (Fig. 9.3). Great care must be taken to divide the mesentery carefully so as to avoid significant devascularization of the Roux limb. The greater omentum can be divided in the middle to permit easier approximation of and less tension on an antecolic gastrojejunostomy.

Figure 9.1 Trocar configuration for standard 5-port technique.

Figure 9.2 Construction of lesser curve-based gastric pouch. The staple line should start horizontally and then turn perpendicularly, directly up toward the angle of His in an effort to create a rectangular pouch.

Figure 9.3 Division of jejunum and its mesentery 30 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz.