INDICATIONS

Reconstruction of the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) that includes fundoplication is indicated in the treatment of (1) gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and (2) symptomatic mechanical obstruction resulting from Type III and Type IV (paraesophageal) hiatal hernia.

GERD

To avoid the pitfalls of indiscriminate surgery seen in the laparoscopic experience of the recent past, surgery for GERD must be used in highly selected patients to treat specific symptoms and reverse or halt documented, severe mucosal damage resulting from quantified abnormal reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. Surgery for GERD should be considered only if (1) a trial of aggressive medical treatment using proton pump inhibitors (PPI) with dose escalation and lifestyle modifications has failed, (2) mucosal damage has been identified and quantified, (3) abnormal gastroesophageal reflux has been documented, and (4) a repairable problem in the reflux barrier has been found.

Symptom Control

Heartburn is the main symptom indication for surgery in GERD patients. There are three typical clinical scenarios: (1) Heartburn initially controlled by PPI therapy that has become refractory or is poorly controlled despite dose escalation, (2) heartburn well controlled, but side effects of PPI therapy are intolerable, and (3) volume regurgitation despite effective heartburn control. GERD-related dysphagia in the above scenarios may not be as effectively treated by surgery, but it is an indication nonetheless. Beware of patients with typical symptoms that do not respond to medication, those demanding immediate surgery for relief of intolerable symptoms, and those with scleroderma, because their outcome with surgery is poor. Age itself should not change these indications. Need for lifelong medical therapy in a young patient with well-controlled symptoms is an indication for surgery only if a durable repair can be ensured.

Atypical symptoms, such as cough, laryngitis, hoarse voice, sore throat, asthma, chest pain, and abdominal bloating, should be associated with typical GERD symptoms and responsive to PPI therapy if surgery is to be considered. If symptoms are only atypical, they must be proven to be GERD related and responsive to PPI therapy or demonstrated to be the result of acid reflux before surgery is prescribed.

Mucosal Injury

Poorly controlled or recurrent ulcerative esophagitis after aggressive PPI therapy is an indication for surgery. Other causes that result in lack of healing, such as pill-induced injury, must be ruled out. Most strictures can be managed initially with medical therapy and dilatation. As with esophagitis, unsuccessful medical therapy or recurrent strictures despite effective medical therapy are indications for surgery. The ability of any therapy to completely reverse Barrett’s esophagus (BE) or prevent its progression to cancer has not been demonstrated; therefore, indications for surgery in a GERD patient with nondysplastic BE are identical to those for the GERD patient without BE.

Mechanical Obstruction

Mechanical obstruction caused by paraesophageal hernias, typically with organoaxial volvulus, is an indication for repair of the EGJ with fundoplication. Uncommonly, this is an acute presentation with ischemia or infarction. More typically, the symptoms are chronic and progressive and include early satiety, postprandial discomfort, attack of unrelenting postprandial epigastric pain, and chronic blood loss secondary to Cameron ulcers.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Obesity

An often ignored but essential part of physical examination is measuring and recording weight and height and calculating body mass index (BMI). Overweight (BMI 25 to 29) and obese (BMI 30 to 34) GERD patients should be counseled on weight loss and encouraged to reach their ideal weight before elective surgery. Because obesity and GERD are interrelated, successful and sustained weight loss may eliminate need for surgery. Although there is disagreement concerning impact of obesity on outcome of antireflux surgery, the health benefits of weight loss in severely (BMI 35 to 39) and morbidly (BMI ≥ 40) obese GERD patients should make weight loss surgery the operation of choice in these patients.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Investigations

The preoperative barium esophagram has been neglected, misused, and in some cases abandoned, with the advent of modern investigations of GERD and hiatal hernia. However, it provides valuable information about the mucosa, esophageal complications, reflux of gastric contents, reflux barrier, and esophageal function. It should, whenever possible, be ordered by the surgeon and performed by a radiologist, experienced in preoperative assessment of GERD and hiatal hernia, who is a member of the multidisciplinary team evaluating and treating the patient. If dysphagia is the predominant symptom and the diagnosis is in question, the examination should start as a timed barium esophagram.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with biopsy has replaced the upright air- contrast phase of the barium esophagram for mucosa evaluation. EGD and biopsy both diagnose and assess esophageal injury by visual and histopathologic mucosal examination. Visual assessment of esophageal injury is graded using the Los Angeles classification. Histopathologic findings, although nonspecific, are confirmatory in the clinical setting of GERD. The finding of specialized columnar epithelium (BE) in the tubular esophagus is secondary to GERD. In the absence of dysplasia, surveillance esophagoscopy and biopsy are required in patients with BE regardless of therapy. EGD should be performed by the surgeon prior to surgery. The finding of a hiatal hernia identifies failure of two elements of the reflux barrier: loss of (1) intra-abdominal esophagus and (2) extrinsic sphincter. The following must be recorded: measurements from the incisor teeth to the squamocolumnar junction, gastric rugal folds, and diaphragmatic hiatus; length of hiatal hernia; length of the esophagus; type of hiatal hernia; presence of volvulus of the intrathoracic stomach; presence of mucosal abnormalities (strictures, rings, etc.); and presence of mural abnormalities (submucosal tumors, leiomyoma, etc.).

The definition of GERD requires causation of symptoms or complications by abnormal reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. Ambulatory pH monitoring performed off medication both quantifies acid reflux and relates symptoms to acid exposure. It has evolved from an in-hospital test to an ambulatory wireless 48-hour study. Once reserved for diagnostic dilemmas, in the 21st century it is essential before any proposed operation. It is invaluable in diagnosing GERD and documenting the preoperative state for later comparison. Excessive acid exposure on pH testing is a surrogate for reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus, and in the majority of patients it is adequate to diagnose GERD. Abnormal pH monitoring is the investigation most predictive of successful outcome of surgery for GERD.1 In the uncommon patient in whom duodenal reflux must be confirmed and quantified, ambulatory bilirubin monitoring is required. Similarly, in the patient in whom nonacid reflux must be assessed, combined impedance and pH monitoring is necessary.

Esophageal manometry excludes unsuspected motility disorders or motility disorders masquerading as GERD, confirms adequate esophageal peristalsis for GERD surgery, and quantifies preoperative resting pressure and relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter for later comparison. High-resolution manometry has replaced conventional manometry because it provides a spatially enhanced pressure topogram, which is a dynamic representation of the esophageal body and reflux barrier. It isolates the esophageal hiatus from the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), increasing understanding of function of the EGJ and facilitating treatment decision-making. For modern esophageal evaluation, high-resolution manometry is invaluable and highly recommended.

If gastric emptying abnormalities are suspected by history or investigations, gastric clearance assessment with radionucleotide tracers is necessary.

Patient Preparation

Patient preparation for surgery is that for general anesthesia and upper GI abdominal surgery. Lifelong smoking cessation and realization of ideal weight and adequate nutrition are important for avoidance of complications following elective surgery and optimizing long-term outcome. A bowel prep is not standard and is reserved for special situations, such as the chronically constipated patient. Perioperative antibiotics and DVT prophylaxis are prescribed.

SURGERY

SURGERY

Positioning and Instrumentation

After placement of an epidural catheter for perioperative pain management and induction of general anesthesia, the patient is placed supine on the operating table. The arms are placed at the patient’s side and secured. The operating table, initially flat, will be placed in 20-degree anti-Trendelenburg position to facilitate exposure. Both a sternal retractor, which lifts the sternum and costal arch up and cephalad, and an abdominal wall retractor, which separates the abdominal wound edges laterally, are used.

Technique

A midline abdominal incision starting at the xiphoid process and extending half the distance to the umbilicus is usually adequate for exposure and repair. Reconstruction of the EGJ follows three principles: restoration of intra-abdominal esophagus, reconstruction of an extrinsic sphincter, and reinforcement of the intrinsic sphincter.

Restoration of Intra-abdominal Esophagus

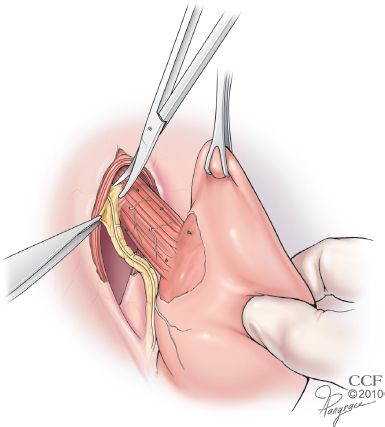

The left lateral segment of the liver is mobilized by dividing the triangular ligament, then retracted laterally to expose the esophageal hiatus. The pars lucida of the lesser omentum over the caudate lobe of the liver is divided. If possible, but not mandatory, the hepatic branch of the vagus and accompanying vasculature should be preserved. This exposes the right crus. Dissection of the right crus is performed on its medial surface inside the hiatus to protect its peritoneal covering. The dissection is carried anteriorly to define the apex of the hiatus and posteriorly to define the confluence of the crura (Fig. 3.1).

The stomach is delivered into the abdomen using a hand-over-hand technique. The short gastric vessels are divided, including the highest branch that typically obscures the inferior portion of the left crus as this vessel passes posteriorly into the retroperitoneum. This vessel is frequently not divided, leading to difficulty with later steps in the operation. This fundic mobilization allows the stomach to be retracted medially, exposing the left crus, which is prepared similarly to the right crus. The dissection inside the hiatus proceeds anteriorly to meet the right crural mobilization at the apex of the hiatus and posteriorly to define the confluence of the crura. These steps divide the “hernia sac.” Division, not removal of the hernia sac (removal is never complete from an infra- diaphragmatic approach), is a key element of this dissection.

Figure 3.1 The left lateral segment of the liver has been mobilized and the lesser omentum divided. Dissection of the right crus is performed on its medial surface inside the hiatus to protect its peritoneal covering. The dissection is carried anteriorly to define the apex of the hiatus and posteriorly to define the confluence of the crura. The hernia sac is divided but not necessarily completely excised. (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2013. All Rights Reserved.)

The hiatal dissection indirectly mobilizes the distal esophagus, which is encircled with an umbilical tape or penrose drain. The dissection of the esophagus then proceeds both bluntly and sharply in the posterior mediastinum until adequate length of intra-abdominal esophagus is obtained. If the pleura is breached, particularly with large paraesophageal hernia mobilization, drains may be placed into the respective pleural spaces.

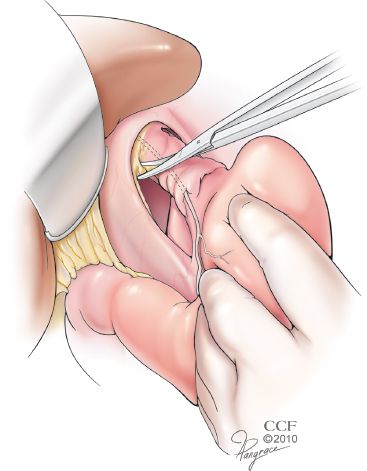

In certain patients, such as those with the much disputed diagnosis of short esophagus, this esophageal dissection alone is inadequate to restore a sufficient length of intra-abdominal esophagus. The diagnosis of a short esophagus should be made preoperatively. It is suspected in patients with a history of peptic stricture or repeated esophageal dilatation, long-segment BE, sliding (Type I) hiatal hernia more than 4-cm long, paraesophageal (Type III and Type IV) hiatal hernia, or nonreducible hiatal hernia on upright air-contrast barium esophagram. In such patients, adequate intra-abdominal length is obtained by adding a Collis gastroplasty. This begins with dissection of the esophagogastric fat pad, which is a key component of the preparation of the abdominal esophagus, regardless of the need for a Collis gastroplasty (Fig. 3.2). This mobilization selectively vagotomizes the gastroplasty segment. A 50-Fr bougie is passed orally and held against the lesser curve and used as a guide and mold for formation of the gastroplasty tube. A 3- to 6-cm long tube of stomach is constructed along its lesser curve using surgical staplers. With adoption of laparoscopy, esophageal lengthening has evolved into a simple wedge gastroplasty, because of technical difficulties presented by laparoscopy and misunderstanding of the principles of constructing a Collis gastroplasty. Predictably, acid production in this unprepared gastric segment perpetuates GERD. A Collis gastroplasty must be added in patients with short esophagus to assure sufficient intra-abdominal esophageal length and thus eliminate one cause of the repair being under tension (Fig. 3.3).

Failure to restore adequate intra-abdominal esophageal length produces a repair under tension that will eventually fail. In patients with failed surgery, review of the operative report may identify inadequate restoration of the intra-abdominal esophagus as a reason for failure of the initial surgery.

Figure 3.2 Mobilization of the esophagogastric fat pad is essential to both identify the EGJ and permit direct apposition of the peritoneal surface of the fundus to the bare surface of the distal esophagus. This selectively vagotomizes the segment, allowing its use as a gastroplasty tube if necessary. (Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2013. All Rights Reserved.)