Foreign Bodies in the Esophagus

Gregory A. Coté

Ikuo Hirano

Foreign body (FB) ingestions are reasonably common and potentially serious events. While 75% to 90% of FB ingestions pass spontaneously and without complication92,97 most FBs retained in the GI tract are found in the esophagus.17,18 Foreign bodies in the esophagus cause the highest mortality and morbidity because of the potential for perforation and associated mediastinitis, pneumothorax, pericarditis, lung abscesses, and cardiac tamponade. Since retention times lasting >24 hours are associated with the highest rates of complications,26 all esophageal FBs should be managed on an urgent basis. Fortunately, success rates for endoscopic management of esophageal FBs typically range from 90% to 100%.10,16,62,66,67,93,97

The location of retained esophageal FBs varies depending on the object ingested and the age of the patient. In children, retained FBs are typically found proximal to the cricopharyngeus muscle, while in adults, they localize above the lower esophageal sphincter or a preexisting stricture.5 While children most commonly present with FB, impaired adults with mental retardation, underlying psychiatric problems, or alcohol intoxication are also at high risk.15 Further, edentulous adults are at risk of FB ingestions, particularly of their dental prostheses.1 Recurrent food impactions occur in patients with esophageal strictures. In addition to the age of the patient, the location of FB impaction is also determined by the characteristics of the object. Large and rigid FBs often lodge in the piriform fossa or the esophagus, while coins and impacted meat are usually found in the proximal and distal esophagus, respectively.49,64

Esophageal FBs can be classified into four categories: sharp foreign objects, blunt foreign objects, iatrogenic objects, and food boluses. The diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to each of these subtypes are discussed. Underlying esophageal disorders that may predispose individuals to FB or food impaction are reviewed.

Diagnosis

The most common symptoms of esophageal FB include dysphagia and odynophagia.6,18 Other symptoms may include chest pain, excessive salivation, regurgitation, and vomiting. Odynophagia may be due to persistent impaction of the FB, but it can also indicate mucosal injury by a foreign body that has already passed. An inability to tolerate salivary secretions indicates complete esophageal obstruction. Respiratory symptoms of cough, dyspnea, or stridor can be seen with aspiration of food or saliva secondary to esophageal obstruction, aspiration of a foreign body, laryngeal trauma, or extrinsic compression of the trachea by proximal esophageal distention. In addition to the nature and timing of self-reported or witnessed FB ingestion, the history should include details of prior episodes of dysphagia, including previous types of FB and the consistency of food that has produced problems in the past. A past history of esophageal or oropharyngeal surgery, caustic injury, radiation, or prior esophageal dilation allows the physician to anticipate likely underlying pathology and level of obstruction. Although gastroesophageal reflux disease is a very prevalent condition, a history of severe heartburn is an important risk factor for peptic stricture. History of atopy—including asthma, allergic rhinitis, or eczema—is present in 75% of patients with eosinophilic esophagitis.

On physical examination, lucid children or adults may be able to identify the material swallowed and point to a particular area of discomfort, although few patients are able to localize the level of impaction reliably.31 Patients are more precise when the impaction occurs proximal to the cricopharyngeus. On the other hand, localization of the FB discomfort to the mid- or lower sternum indicates esophageal rather than pharyngeal retention. Localization to the suprasternal notch can be seen with either pharyngeal or esophageal retention. Particular attention should be paid to crepitus, tenderness, or erythema in the neck, each of which suggests an oropharyngeal or proximal esophageal perforation. Perforation at the level of the esophagogastric junction may occur distal to the diaphragmatic hiatus. Therefore, a thorough abdominal exam should include signs of peritonitis or bowel obstruction, both of which would preclude endoscopic management.35

Radiographic evaluation of the chest and neck can be helpful to locate most artificial objects and steak bones as well as to evaluate for the presence of mediastinal or peritoneal free air.29 However, chicken or fish bones, plastic, wood, and most glass are radiolucent. Both anteroposterior and lateral views should be obtained and can differentiate an esophageal from a tracheal foreign body. Barium or Gastrografin studies should generally be avoided in esophageal FB patients. The oral contrast agents place patients at increased risk for aspiration during endoscopy and also make endoscopic extraction of retained FBs more difficult. In addition, the hypertonicity of Gastrografin carries a significant risk for pulmonary edema if this agent is aspirated. Moreover, a normal radiographic examination does not generally preclude the need for endoscopy in a symptomatic patient. One setting where oral contrast studies are used is in confirming the presence of an esophageal perforation suspected by exam or plain film findings. Computed tomography (CT) scans have proven useful in identifying ingested bones lodged in the esophagus36; 3D reconstruction may improve this technology.89 Ingested packets of contraband are an important limitation of CT imaging.37 Handheld metal detectors can localize the majority of swallowed metallic items and have been proposed as a means of reducing radiation exposure in children.8,34

Despite negative imaging, persistent symptoms warrant endoscopic evaluation.35,48 Rigid esophagoscopy or direct laryngoscopy should be used initially for impacted objects proximal to the level of the hypopharynx and cricopharyngeus muscle.29 While certain proximal items can be retrieved using a transnasal bronchoscope, flexible gastroscopy is more effective and equally tolerable.30 Specific aspects of the endoscopic management of esophageal FBs are discussed below.

Sharp and Blunt Foreign Objects

Most series report that coins are the most common foreign objects ingested by children, whereas chicken and fish bones predominate in adults.73 While the impaction of any object in the esophagus can be complicated by perforation,20 sharp objects (animal or fish bones, toothpicks, metallic objects, medication blister packs) are associated with a higher rate of perforation.28,35 Newell et al. even reported a complicated series of five patients who ingested bread clips.75 While many sharp objects will pass through the GI tract uneventfully, a sharp object identified in the esophagus should be removed emergently. Since the incidence of complications may be as high as 35%,37 endoscopic removal of any sharp object should be attempted if it is localized proximal to the duodenum.

Several unique issues arise for three particular blunt objects: coins, batteries, and narcotic packets. Coins are the most commonly ingested artificial objects, particularly in the pediatric population.5 Symptomatic patients should undergo urgent removal to reduce the rate of complications. A variety of extraction devices have been described, including balloon-tipped catheters,45,66 esophageal bougies,22 laryngoscopes,22,24 or flexible endoscopes.95 While none of these methods are free of risk, laryngoscopic or endoscopic extraction is generally the preferred approach. Some experts advocate a period of expectant management for the asymptomatic patient with a coin lodged in the esophagus who has no known underlying pathology.94 A study of 168 asymptomatic patients <21 years of age observed varying rates of spontaneous passage depending on the location of impaction: 14% if in the proximal third, 43% if in the middle third, and 67% if in the distal third.94 Once a coin has reached the stomach, it is passed spontaneously by all patients. Given the higher rate of complications after >24 hours, expectant management should be limited to ≤18 hours.

Disk or button batteries usually pass spontaneously, although case reports have described liquefaction necrosis and perforation related to the extrusion of concentrated potassium hydroxide from alkaline batteries. Esophageal injury can also result from pressure necrosis or low-voltage electrical burns. In a review of 2,382 cases, only 2 severe events were reported.65 A smaller series from Taiwan reported similar favorable outcomes in 25 subjects who presented after ingesting button batteries.27 A total of 19 cases of esophageal injury due to battery ingestion have been reported since 1979, all of which occurred with batteries >20 mm in diameter.102 Since batteries are easily recovered with retrieval baskets or nets, endoscopic removal of all batteries lodged in the esophagus is recommended.35 Rat-tooth or grasping forceps should be avoided owing to the risk of battery puncture, with resultant leakage of caustic contents. If batteries have already passed into the stomach, endoscopic retrieval can be reserved for those that remain in the stomach on repeat radiography at 48 hours or those with diameter >20 mm.65

Cocaine wrapped in plastic or latex condoms (used for “body packing”) is often visible on plain radiographs or CT scans, although cases of negative radiography have been reported.37,53 Since rupture and leakage of contents can be lethal, endoscopic extraction and the use of gastric lavage are not recommended. Conservative management is generally advised, with surgical intervention for signs of obstruction, packet rupture, or lack of progression.35,48,97

Endoscopic Management of Foreign Bodies in the Esophagus

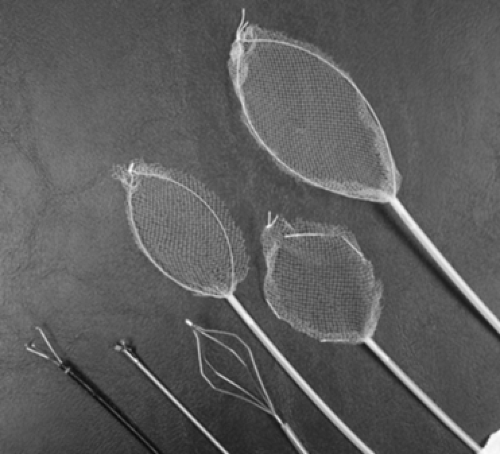

The endoscopic approach to removing sharp objects varies depending on the size, position, and location of the item. Objects >5 cm in length usually require endoscopic or surgical removal because they cannot traverse the pylorus and duodenum. Prior to endoscopy, several instruments should be readily available, including rat-tooth and alligator forceps, a polypectomy snare and grasper, baskets, short and long overtubes, and a foreign body protector hood (Fig. 145-1).35,74 If possible, a practice session with a similar object outside of the patient before endoscopy

may be helpful. Snares and forceps are most useful for sharp objects, whereas retrieval nets and baskets seem to be most effective for small, blunt objects.39,57 Retrieval baskets are now available in a variety of shapes and sizes.

may be helpful. Snares and forceps are most useful for sharp objects, whereas retrieval nets and baskets seem to be most effective for small, blunt objects.39,57 Retrieval baskets are now available in a variety of shapes and sizes.

In addition to facilitating repeated endoscopic intubation, overtubes provide airway protection and reduce the risk of mucosal lacerations during the removal of sharp objects (Fig. 145-3). Esophageal intubation with an overtube carries the risk of hypopharyngeal injury. Passage of the overtube may not be feasible in the setting of a very proximal FB obstruction. Esophageal injury is also a concern in patients with proximal esophageal strictures secondary to caustic ingestion, radiation, or eosinophilic esophagitis when the diameter of the overtube exceeds the diameter of the stricture. In addition, bypassing the upper esophageal sphincter with an overtube interferes with air distention, making visualization of the esophageal lumen more difficult. Short overtubes can be used for airway protection and to shield the upper esophagus and pharynx, while longer overtubes confer additional protection for the distal esophagus and lower esophageal sphincter. While longer overtubes are more cumbersome to use, they are particularly helpful for the removal of sharp objects located in the stomach. Longer overtubes mean greater resistance and less maneuverability for flexible endoscopes.

FB protector hoods are typically less cumbersome than overtubes and more comfortable for patients; these devices are particularly useful for the removal of objects from the stomach that may injure the lower esophageal sphincter during extraction (Fig. 145-2).11,12,13 Some cases have been reported involving the use of an overtube to facilitate esophageal dilation and passage of an impacted object into the stomach and then employing a protective hood to remove the item.82 To further reduce the risk of mucosal lacerations with extraction, the sharp end of the object should be pointed distally when grasped; for example, a safety pin can be removed by grasping the open ring at the elbow of the safety pin so that it can be extracted with the sharp end trailing behind (Fig. 145-4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree