Foregut Cysts of the Mediastinum in Infants and Children

Anthony Chin

Marleta Reynolds

Bronchopulmonary foregut malformations, so named by Gerle11 in 1968, encompass a full spectrum of rare, benign congenital aberrations that arise during the development of the embryonic foregut. Terms that have been used to describe these malformations include bronchogenic cysts, duplication cysts or enterogenous cysts, and neuroenteric cysts. Bronchopulmonary foregut malformations may include a broader spectrum of disorders with associations with pulmonary sequestrations, congenital cystic adenomatoid malformations, congenital lung cyst, and congenital lobar emphysema. The close embryonic relationship, clinical presentation, radiographic findings, and overlapping features has led to the collective categorization of these entities as foregut aberrations or cysts. This chapter specifically addresses the bronchogenic and enteric duplication variants of this malformation.

Incidence

According to Meza et al.,20 11% to 18% of mediastinal masses in infants and children are attributable to foregut malformations. There appears to be a slightly higher distribution in males than females. Bower and Kisewetter6 report that 7.5% of mediastinal masses in children are brochogenic in origin and 7% are esophageal in origin. In Holcomb and associates’12 series of 96 patients with alimentary tract duplications, 21% of the duplications were esophageal and 3% of the duplications were thoracoabdominal. Autopsy series compiled by Arbona et al.,1 revealed 6 esophageal cysts in 49,196 autopsies (1:8,200).

Embryology and Etiology

The primitive foregut gives rise to the pharynx, respiratory tract, and upper portion of the gastrointestinal tract from the esophagus to the duodenum at the ampulla of Vater. Foregut malformations are thought to originate from the region of the laryngeotracheal groove, which develops from the primitive foregut in the third to fourth week of gestation. The stage of embryonic development and separation during which the error occurs seems to play a role in the location and type of malformation. Cysts that arise late in gestation tend to be in the lung parenchyma and are more peripheral. No unifying theory explains the spectrum of anomalies. In Barnes and Pilling’s review,3 ischemia, trauma, infection, and adhesions have been postulated as potential causes. The split notochord theory offers some explanation to enteric and neuroenteric anomalies. Foregut malformations have been seen in studies performed by Beasley and colleagues4 of Adriamycin-induced rat models, and studies by Arsic et al.2 reveal emerging evidence that altered signaling of the Shh-GLi pathway may contribute to some foregut malformations. The exact embryogenesis is yet to be fully elucidated.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with foregut malformations may present with symptoms of chest pain or respiratory complaints of dyspnea, cough, pneumonia, recurrent asthma, hemoptysis, and cyanosis. They may have gastrointestinal complaints of vomiting, dysphagia,

anorexia, weight loss, and/or gastrointestinal bleeding. The presentation may be asymptomatic, or it may present incidentally on radiographic examination. The manner of presentation seems to depend on several factors, including the anatomic location, age at presentation, mass effect of the lesion, and potential complications that may result from the lesion.

anorexia, weight loss, and/or gastrointestinal bleeding. The presentation may be asymptomatic, or it may present incidentally on radiographic examination. The manner of presentation seems to depend on several factors, including the anatomic location, age at presentation, mass effect of the lesion, and potential complications that may result from the lesion.

The anatomic location of these malformations may be quite variable. Sulzer and associates’32 review of 40 cysts in all age groups found that two-thirds of the cysts were located in the upper half of the mediastinum and often associated with the trachea or the tracheal bifurcation. When they were found in the lower half of the mediastinum, the lesions were associated with the esophagus. St-Georges and colleagues30 reported that 22 of 66 bronchogenic cysts were found in the middle mediastinum and 43 of 66 were found in the posterior mediastinum. Cysts have also been located intrapericardially, intrathymically, and in the region of the paravertebral sulcus. They have been excised from within the pulmonary ligament and may reside outside the mediastinum, with numerous examples of subcutaneous bronchogenic cysts. These cysts tend to be found in the suprasternal area and scapular region.

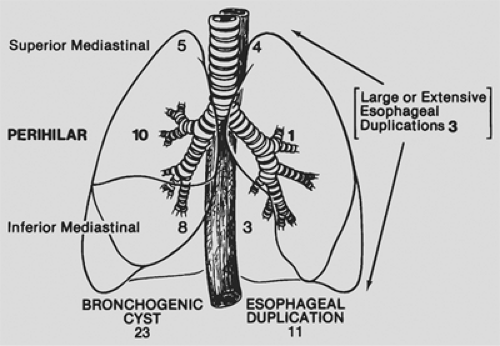

The age at presentation may range from the prenatal period into late adulthood. Reviews of bronchogenic cysts by St-Georges et al.30 (n = 86) and Suen et al.31 (n = 42) revealed that symptoms were present in 72%, 50%, and 94% of patients, respectively. The most common complaint was chest pain. Nobuhara and associates23 reviewed 68 children and found that 20% were asymptomatic and the majority had either respiratory (54%) or gastrointestinal (13%) complaints. Ribet and colleagues25 report that children with bronchogenic malformations are more often symptomatic from compressive symptoms than adults (70.8% versus 60%). They believe this is because the cysts in children tend to be situated above and at the level of the hilum. Snyder and associates29 described 34 infants and children with mediastinal foregut cysts. The locations of these cysts are shown in Figure 201-1. Of the total, 23 children had bronchogenic cysts and 11 had enteric cysts; 12 were asymptomatic. Most of the others developed symptoms related to the location of the cyst and presented with symptoms of pneumonia, major airway obstruction, or esophageal obstruction (Table 201-1). Regardless of the presentation, further workup and a planned surgical excision is necessary when a foregut malformation is suspected.

Figure 201-1. Location of foregut cysts of the mediastinum in 34 infants and children. (From Snyder ME, et al. Diagnostic dilemmas of mediastinal cysts. J Pediatr Surg 1985;20:810. With permission.) |

Table 201-1 Mediastinal Foregut Cysts: Clinical Presentation in 34 Children | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Radiographic Investigation

Standard Radiography

Foregut duplications are best investigated initially with standard posteroanterior and lateral x-rays. Zhang and colleagues34 believe that an x-ray exam should also include the abdomen, as mediastinal lesions may extend into the abdomen and communicate with enteric duplications. Suen and his group31 report that 88% of the patients in their series had an identifiable lesion on standard chest x-ray. Most cysts were homogenous, smooth, and round or ovoid in appearance and are located in the middle or posterior mediastinum. These lesions may be missed when located in the subcarinal location or when masked by pneumonia or other inflammatory processes. Cysts that compress the adjacent trachea or bronchus may lead to unilateral air trapping and mediastinal shift (Fig. 201-2). Occasionally, a cyst may be filled with air, and the chest radiograph shows a well-defined, radiolucent spheric or oval mass (Fig. 201-3).

Contrast Studies

A contrast esophogram may demonstrate extrinsic compression or distortion of the esophagus (Fig. 201-4). It may show a communication between a duplication and the intestinal tract. In the series of mediastinal cysts evaluated by St-Georges and colleagues,30 54% of the patients had positive findings on esophogram. The CT scan has replaced the esophagram as the diagnostic modality of choice because it can better differentiate this lesion from other masses in the mediastinum.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree