Foregut Cysts of the Mediastinum

Pasquale Ferraro

Jocelyne Martin

André C. H. Duranceau

Mediastinal cysts are common lesions encountered in children and adults. Most are congenital lesions, and they account for 20% to 32% of all primary masses of the mediastinum.39,46 When Takeda and associates55 reviewed their series, the 95 patients with mediastinal cysts in their adult population accounted for 14% of all mediastinal masses; 47 were bronchogenic cysts and 4 esophageal duplications. Despite the frequent discovery of these cysts in infancy and childhood, half or more of these cysts are not identified until the third or fourth decade of life. In the authors’ experience, reported by St-Georges and associates,51 in regrouping all cystic lesions of the mediastinum found in nonpediatric university-affiliated hospitals, 32% of all cysts were found in patients <20 years of age, whereas 68% were in patients >20 years of age.

Classification of Mediastinal Cysts

The classification of mediastinal cysts is usually based on their etiology (Table 202-1). Foregut cysts are the result of an abnormal budding or division of the primitive foregut. Also called enterogenous cysts, they are most frequently divided into categories based on their histologic features and embryogenesis.

Bronchogenic cysts occur mostly along the tracheobronchial tree and are usually found behind the carina. Most often they are unilocular and lined by ciliated columnar epithelium with focal or extensive squamous metaplasia. Rosai,42 Coulson,11 Sternberg,50 and Marchevsky and Kaneko31 have described how the walls of these cysts may contain hyaline cartilage, smooth muscle, bronchial glands, and nerve trunks. Bronchogenic cysts account for 50% to 60% of mediastinal cysts and are usually found in adults. They can be intrapulmonary or extrapulmonary and rarely show a communication with the airway. These cysts may extend below the diaphragm as dumbbell cysts.64

Esophageal cysts are less common than bronchogenic lesions; they are characterized by a double layer of smooth muscle in their walls. Most of them are found embedded in the wall of the lower half of the esophagus. Their lining may be squamous, ciliated columnar, or a mixture of both. Distinction from bronchial cysts may be difficult or even impossible; the best evidence in favor of their esophageal etiology is when they are totally within the esophageal wall and covered by a definite double layer of smooth muscle. They are usually not in communication with the esophageal lumen. Two theories are suggested by Abel,1 Coulson,11 Marchevsky and Kaneko,31 Rosai,42 and Sternberg50 to explain the development of esophageal cysts: persistent vacuoles in the wall of the foregut or an abnormal budding from the foregut.

This chapter focuses on the most common cystic lesions encountered in the mediastinum of the adult. These are the bronchogenic cysts and the esophageal cysts of the foregut.

Bronchogenic Cysts

Embryogenesis

The bronchogenic foregut cysts are believed to result from sequestration of cells from the region of the laryngotracheal groove during early embryologic development. During the third week of gestation, the laryngotracheal groove or primitive respiratory system develops as a ventral diverticulum located in the floor of the foregut, just caudal to the pharyngeal pouches. This diverticulum later transforms into a tube that becomes the primitive bronchial tree. After the fourth week,

two enlargements develop distally; these become the future bronchial and lung buds. By the 35th day, the lobar bronchi appear.

two enlargements develop distally; these become the future bronchial and lung buds. By the 35th day, the lobar bronchi appear.

Table 202-1 Classification of Mediastinal Cysts | |

|---|---|

|

Abnormal budding of the bronchial tree may lead to abnormal tracheal and bronchial cystic masses called bronchogenic cysts. When this abnormal budding occurs early during gestation, the cysts tend to be located within the mediastinum and seldom communicate with the bronchial tree. Cysts that arise later during development are more peripheral and are located within the lung parenchyma. These intraparenchymal cysts often have a bronchial communication.

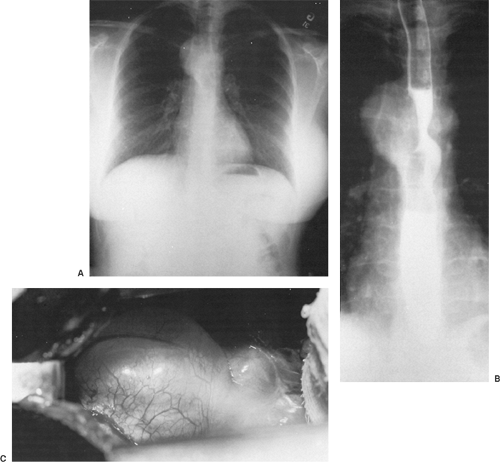

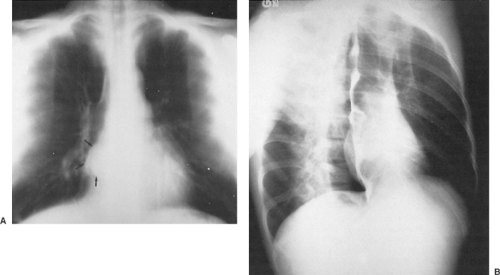

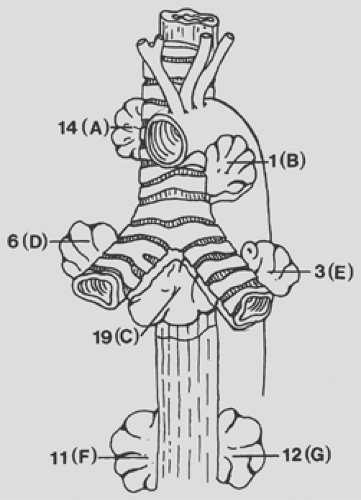

The majority of the bronchogenic cysts are in close anatomic relationship with the tracheobronchial tree (Fig. 202-1) or the esophagus (Fig. 202-2) in the visceral compartment of the mediastinum. A bronchogenic cyst may occasionally even extend below the diaphragm as a dumbbell cyst. Amendola and colleagues2 reviewed nine cases of dumbbell cysts reported in the literature and added one of their own discovered in this latter location. Coselli and associates10 described a bronchogenic cyst located wholly within the abdomen in the region of the tail of the pancreas.

Three other similarly located cysts have been described by Miller35 and Sumiyoshi53 and their colleagues as well as by Murley and Lenz.37

As noted, cysts developing late in the course of embryologic development may be located within the parenchyma of the lung and in the adult represent approximately 25% of all bronchogenic cysts.

Pathology

Bronchogenic cysts are most often spherical, unilocular cystic masses in contact with the tracheobronchial tree. Infrequently the cysts may be lobulated, multiloculated, or rarely multiple. They may be located near or within the wall of the esophagus, in the lung, or even within the pericardial sac. Maier30 divided their locations into five groups: paratracheal, carinal, hilar, paraesophageal, and miscellaneous. In our experience, in using the tracheobronchial bifurcation as a dividing line, 23% of the cysts were located in the superior portion of the chest, whereas 77% were below the tracheal carina. Roughly one-third were in the middle mediastinum, whereas the other two-thirds extended to the limits of the posterior portion of the mediastinum and even to the paravertebral area (Fig. 202-3). The fifth group, miscellaneous, are located in abnormal locations. These cysts include the aforementioned dumbbell cysts as well as those in the anterior mediastinal compartment, pericardial cavity, paravertebral sulcus, and abdomen. Coselli and associates10 suggested that these cysts possibly arise from abnormal budding of the primitive foregut that migrates into the abdomen before fusion of the pleuroperitoneal membranes. Buddington8 reported a cyst located within the diaphragm. Magnussen29 and Dubois13 and their associates reported a bronchogenic cyst in the presternal area and supraclavicular spaces, respectively. Gomes and Hufnagel,19 among others, reported an intrapericardial location. Swartz et al.54 described an enteric cyst attached directly to the epicardium of the left ventricle. In the series collected by us, the location of the 86 bronchogenic cysts was mediastinal in 66 patients and intrapulmonary in 20.

As observed by Sulzer and associates52 in their series of 40 bronchogenic cysts, more than 85% of these are in close association with either the tracheobronchial tree or the esophagus. Two-thirds of these cysts were located in a paratracheal or subcarinal location; the remaining third were paraesophageal in location in the lower half of the chest.

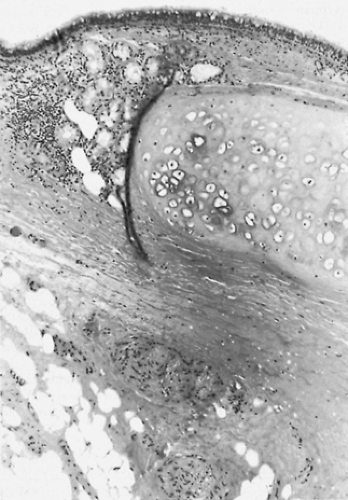

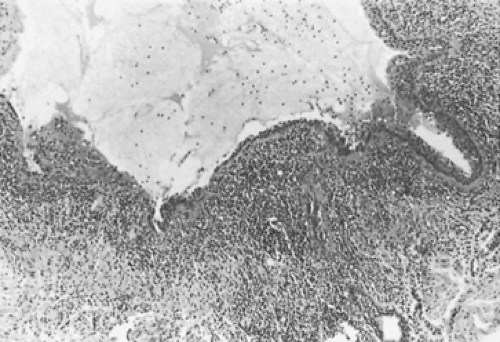

The cysts contain a whitish-gray mucinous material but may contain brownish inspissated material. The common lining is a single layer of respiratory epithelium ciliated columnar cells (Fig. 202-4). This layer of cells may be cuboidal or a simple flattened epithelial layer. Varying degrees of squamous metaplasia can be present. A lamina propria may contain bronchial glands, connective and smooth muscle tissue, and cartilage. At times, in the presence of infection, the cyst may contain frank pus. With infection, the epithelial layer lining the cyst may be absent (Fig. 202-5).

Clinical Features

Bronchogenic cysts are found somewhat more often in men than in women, although in our series and that of Takeda the ratio was reversed. Many in the adult are asymptomatic, but contrary to a widely held belief, as espoused by Maier30 and Wychulis and associates,62 well over half are or will become symptomatic because of compression of the airway or the esophagus or the presence of infection. The latter may be caused by perforation into either of the former structures, but the infection most often occurs without such a communication.

Figure 202-4. Photomicrograph of the wall of the bronchogenic cyst shown in Figure 202-1 reveals an internal surface lined by characteristic respiratory epithelium. A cartilaginous plate is present beneath the mucosal lining. |

Figure 202-5. Photomicrograph of wall of the resected infected bronchogenic cyst shown in Figure 202-2 with absence of a portion of the mucosal lining due to the inflammatory process. |

In the series reported by Sirivella and associates,48 which included individuals with nonspecific and enterogenous cysts, 16 of 20 patients were symptomatic and the most common complaints were cough, dyspnea, dysphagia, and chest pain. Most patients in Zambudio’s series complained of chest pain.64

In our series, published by St-Georges and coworkers,51 66.6% of the patients with mediastinal bronchogenic cysts were symptomatic and the majority (two-thirds) had two or more symptoms. These are summarized in Tables 202-2 and 202-3. When the cyst is in the mediastinum, substernal pain is the most common symptom. This is likely the result of irritation or inflammation of the surrounding parietal or mediastinal pleura. Dysphagia, dyspnea, and cough are all caused by compression or irritation of bronchi or the esophagus by the cyst. Expectoration of purulent sputum is seen in 7.5% of the mediastinal cysts and indicates either infection of the cyst with fistulization or, more likely, pneumonia in the adjacent compressed lung. Actually, 26 of 66 (39.3%) of our patient population were observed conservatively and 15 of 26 (57.6%) developed symptoms while the abnormal mass was being observed conservatively. If a complication occurs in a radiologically detected cyst located in the mediastinum, nearly one-third of these patients will remain asymptomatic. These lesions may then lead to further difficulties.

Complications

Eighteen patients (27%) had a complicated cyst, as documented by gross and histopathologic examination, but in none did this

complication result in a major illness (Table 202-4). Inflammation of the cyst wall with or without mucosal ulcerations was observed in 18% of the patients, and this finding was often associated with chest pain. True cyst infection with positive bacteriology was uncommon, and frank communication with the tracheobronchial tree was documented in three patients who presented with dyspnea, fever, and productive cough. Communication with the esophagus or the pericardial cavity was not observed.

complication result in a major illness (Table 202-4). Inflammation of the cyst wall with or without mucosal ulcerations was observed in 18% of the patients, and this finding was often associated with chest pain. True cyst infection with positive bacteriology was uncommon, and frank communication with the tracheobronchial tree was documented in three patients who presented with dyspnea, fever, and productive cough. Communication with the esophagus or the pericardial cavity was not observed.

Table 202-2 Incidence of Symptoms Associated With Mediastinal Bronchogenic Cysts | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

Table 202-3 Symptoms Associated With Mediastinal Bronchogenic Cysts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree