There are compelling reasons for interventional cardiologists to undertake percutaneous treatment of head to toe noncoronary atherosclerotic vascular diseases (1). Atherosclerosis is a “systemic” disease that often involves multiple vascular beds commonly causing coronary and noncoronary vascular problems in the same patient (2–4). There is general agreement that there is a shortage of trained health-care providers necessary to meet the rapidly increasing demand for percutaneous revascularization, particularly with regard to acute stroke and intracranial intervention. Interventional cardiologists possess the technical skills necessary to perform noncoronary vascular intervention but, in general, lack a comprehensive knowledge base regarding the specialty of vascular medicine. In recognition of the need for adult cardiovascular medicine trainees to gain broader expertise in vascular medicine and vascular intervention, a Core Cardiology Training Symposium (COCATS-11) has been developed (5,6).

Noncoronary vascular disease involving the extremities, visceral and renal organs, and brain is frequently an important aspect of the management of patients with heart disease. Renovascular hypertension is the most common cause of secondary hypertension in patients with atherosclerosis. Renovascular hypertension, causing resistant hypertension, negatively impacts the medical management of angina pectoris and congestive heart failure. Peripheral vascular symptoms, such as claudication, impair the effectiveness of cardiovascular rehabilitation programs. Coronary artery atherosclerosis is the most common cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease.

FEASIBILITY OF CARDIOLOGISTS PERFORMING NONCORONARY VASCULAR INTERVENTION

As experienced coronary interventionalists, we reported our initial experience in peripheral angioplasty in 164 consecutive patients over a 20-month period (7). Prior to performing angioplasty, we observed the performance of peripheral angioplasty in several angiographic laboratories performing high-volume peripheral angioplasty, we were proctored for our initial cases by a qualified outside operator, and our initial cases were reviewed and discussed with an experienced vascular surgeon.

Lower extremity percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) was performed in 116 patients, upper extremity PTA in 30 patients, and renal artery PTA in 18 patients. Successful results were obtained in 92% (191/208) of the lesions attempted, with a successful PTA in 99% (155/157) of stenoses versus 71% (36/51) of occlusions (p 0.01). In no patient did a failed attempt result in worsening of the patient’s clinical condition or the need for emergency surgery. The overall major complication rate of 4.3% (7/164) was similar to other studies published in the literature.

Our experience supported the hypothesis that experienced interventional cardiologists, working in partnership with vascular surgeons, possessed the necessary technical skills to perform peripheral vascular angioplasty in a safe and effective manner. We relied on our vascular surgery colleagues to provide guidance in patient and lesion selection, which compensated for our limited knowledge regarding vascular medicine. Our results did not demonstrate a learning curve. The percentage of patients with totally occluded vessels (25%) and the average lesion length (5.8 ± 8.0 cm) attests to the relatively difficult lesions we routinely accepted for treatment.

Achieving a success rate of 92% for all lesions and a 99% success rate for stenoses suggested that coronary angioplasty skills are transferable to the treatment of noncoronary vascular lesions quite effectively. The fact that success rates were higher for non–total occlusions and lesions of shorter length were consistent with the reported outcomes for vascular intervention in the literature.

Because the risks of diagnostic aortic arch and cerebral angiography add to the risks of revascularization of the carotid artery, the most highly skilled angiographer, regardless of primary specialty, should perform these studies. We investigated the quality and risk of diagnostic cervical–cerebral angiography in the hands of experienced interventional cardiologists (8). We reviewed a total of 189 patients with 191 diagnostic catheter procedures over a 5-year period. There was only one neurologic complication (0.52%), which compares favorably to published results. There is good evidence that the catheter skills of experienced cardiologists compare well with those of other specialists for the safety and quality of noncoronary angiography.

FELLOWSHIP TRAINING IN NONCORONARY DIAGNOSTIC ANGIOGRAPHY

Cardiology fellows currently receive invasive training in both cardiac and noncardiac angiography (9). An example of this type of experience includes ascending, descending, and abdominal aortography. Additionally, angiographic studies may include selective angiography of the aortic arch vessels, mesenteric vessels, renal arteries, and iliofemoral arteries. Another example is the routine performance of selective angiography of the subclavian, internal mammary, and gastroepiploic arteries to determine patency of coronary bypass grafts. Screening renal angiography is frequently done in patients at increased risk for renal artery stenosis with clinical indications for revascularization (10). Finally, routine imaging of the iliac and femoral arteries is commonly performed if there is difficulty advancing catheters or prior to placement of vascular closure devices.

Cardiologists performing noncardiac angiography are responsible for the accurate interpretation of the images they obtain. Physicians must accept the liability for errors or omissions in their interpretation of angiography studies, just as they do for coronary angiography. Physicians who feel insecure in their ability to interpret these films may ask for assistance or overreading of the films by a qualified physician. Peer review of angiographic studies, in a nonthreatening environment, leads to improved quality of peripheral angiographic studies and provides opportunities for less experienced angiographers to enhance their understanding of peripheral vascular anatomy, collateral circulations, and anatomic variations.

FELLOWSHIP TRAINING REQUIREMENTS FOR NONCORONARY VASCULAR INTERVENTION

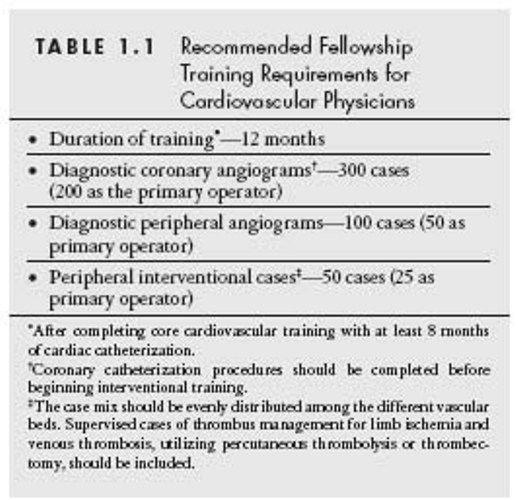

The American College of Cardiology (ACC)’s COCATS document provides guidelines for training in catheter-based peripheral vascular interventions (5,6). For the cardiovascular trainee wishing to acquire competence as a peripheral vascular interventionalist, a minimum of 12 months of training is recommended (Table 1.1). This period is in addition to the required core cardiology training and a minimum of 8 months in diagnostic cardiac catheterization in an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited fellowship program (9). The prerequisite for Level 3 training in peripheral vascular interventions includes Level 1 training in vascular medicine, and Level 1 and Level 2 training in diagnostic cardiac catheterization. Requirements for Level 3 training in peripheral vascular interventions can be fulfilled during fourth year of interventional training dedicated to peripheral vascular interventions or concurrently with coronary interventional training (6).

It is recommended that a cardiology fellow perform 300 coronary diagnostic procedures, including 200 with supervised primary responsibility before beginning interventional training (9). The trainee in an ACGME-accredited program should participate in a minimum of 100 diagnostic peripheral angiograms and 50 noncoronary vascular interventional cases during the interventional training period (11). The case mix should be evenly distributed among the different vascular beds. Cases of thrombus management for limb ischemia and/or venous thrombosis, utilizing percutaneous thrombolysis or catheter-based thrombectomy, should be included.

Advanced training in peripheral vascular intervention may be undertaken concurrently with fourth year of training for coronary interventions (6). Peripheral vascular interventional training should include experience on an inpatient vascular medicine consultation service, in a noninvasive vascular diagnostic laboratory, and experience in longitudinal care of outpatients with vascular disease. Comprehensive training in vascular medicine (Level 2) is not a prerequisite for noncoronary interventional training.

ALTERNATIVE TRAINING PATHWAYS FOR PVD INTERVENTION

Many physicians with specialty training and board certification in interventional cardiology are currently performing peripheral vascular (noncoronary) interventional procedures. These physicians have received either formal training in accredited programs or on-the-job training. Unfortunately, there currently exists little or no cooperation between the specialty training programs with regard to peripheral vascular interventional training.

An ongoing “turf-war” over the provision of these services between competing subspecialties in many hospitals is not in the best interest of patients. Several professional societies including the ACC, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Cardiovascular Interventionists, the Society of Cardiovascular Interventional Radiologists, the Society of Vascular Surgery, and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) have published disparate guidelines for the performance of peripheral angioplasty (12–17).

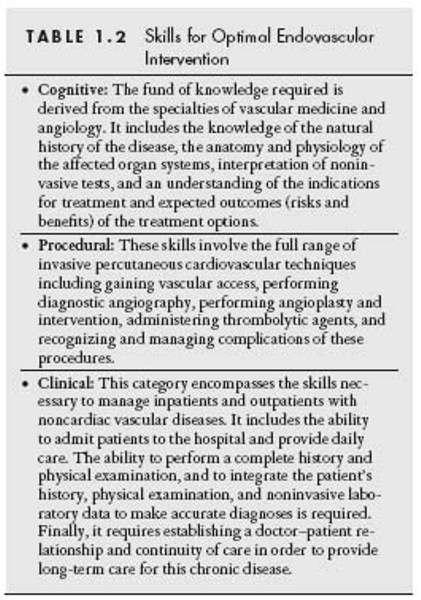

The realization that there is a need for cardiologists to provide noncoronary vascular care to patients with concomitant peripheral vascular disease has prompted revision of prior guidelines that were not “cardiology” specific (11,18). This was done in order to provide a more focused view of the role of the cardiologist, specifically the interventional cardiologist, in the management of these patients. Cardiologists with widely varying backgrounds and clinical experience are currently performing peripheral vascular intervention. Competency to perform peripheral vascular percutaneous interventions can be broken down into three categories or skill sets (Table 1.2).

Unrestricted Certification

Completion of at least 100 diagnostic peripheral angiograms, with a minimum of 50 peripheral interventional procedures, has been recommended for unrestricted certification (Table 1.3) (11). The physician should have been the supervised primary operator for one half of the procedures. These procedures should be performed under the guidance of a credentialed noncoronary vascular interventionalist.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree