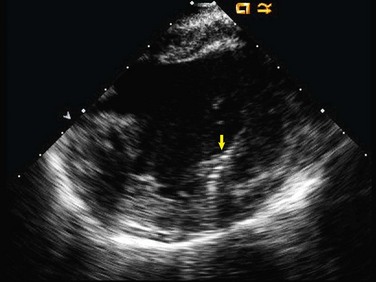

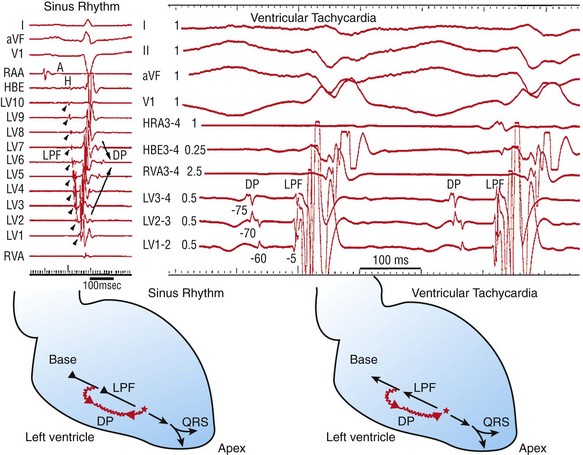

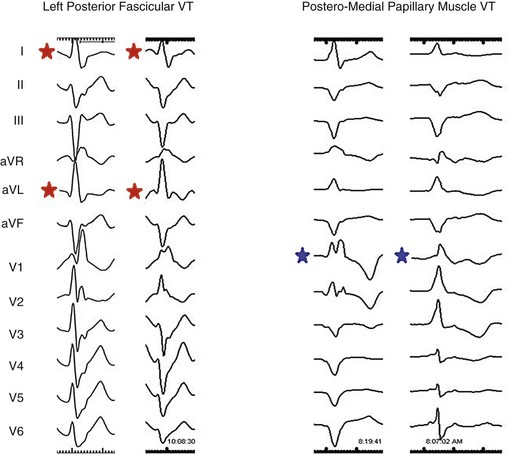

82 Although most patients with VT have structural heart disease, 10% have idiopathic VT, occurring in the setting of a structurally normal heart. Among idiopathic VTs, those arising from the right or left ventricular outflow tract are most common, followed by fascicular VT, which accounts for between 7% and 12% of idiopathic VTs.1,2 Left posterior fascicular VT is the most common, with a narrow right bundle left superior axis QRS morphology. Left anterior fascicular VT is less common and has right bundle right inferior axis QRS morphology. These tachycardias are also referred to as verapamil-sensitive fascicular tachycardias, given their tendency to slow or terminate with intravenous verapamil, as originally described by Belhassen and colleagues.3 Fascicular VT typically manifests in young adulthood with a slight male preponderance.4,5 Presentation consists of palpitations, presyncope and, rarely syncope, but not sudden cardiac death. Incessant, fascicular VT has been reported to cause tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy.6 In some patients, the arrhythmia may manifest only during exercise. The predominant mechanism of fascicular VT is macroreentry using the left posterior (or less commonly anterior) fascicle and abnormal Purkinje tissue or adjacent ventricular myocardium with decremental properties, as elegantly demonstrated by Nogami and others, with the use of multipolar catheters positioned along the inferior left ventricular (LV) septum.7 During sinus rhythm, anterograde conduction occurs over the left posterior fascicle, as well as over the abnormal, slowly conducting Purkinje/adjacent ventricular tissue, with anterograde and retrograde wave fronts colliding within that abnormal tissue (Figure 82-1, top and bottom left). During most cases of macroreentrant fascicular VT, retrograde conduction occurs over the left posterior fascicle and anterograde conduction over the abnormal Purkinje/adjacent ventricular fibers (see Figure 82-1, top and bottom right). Evidence of macroreentry includes induction with atrial or ventricular programmed stimulation. Entrainment can be performed from the atrium or the ventricle with constant fusion when pacing at a fixed cycle length and progressive fusion when pacing at faster cycle lengths.8 The VT circuit likely encompasses most of the length of the fascicle. Wen and colleagues identified the exit site of VT along the apical aspect of the inferior LV septum, as defined by the earliest ventricular activation relative to the QRS complex.9 They then terminated VT with ablation performed a mean of 3.1cm more basally along the septum, proving that the circuit is of considerable size. Figure 82-1 Macroreentrant Circuit of Fascicular Ventricular Tachycardia Focal arrhythmias have also been described from the fascicular system with an automatic or triggered mechanism.10,11 Papillary muscle VT is likely a focal arrhythmia, originating from the distal Purkinje network.12 Evidence of a focal mechanism includes induction by isoproterenol infusion and burst pacing, but not programmed stimulation, inability to entrain, and repetitive, nonsustained bursts of spontaneous VT. No defined scar or low-voltage substrate has been identified for fascicular VT. Controversy persists regarding whether false tendons or fibromuscular bands connected to the left ventricular septum provide the anatomical basis for the macroreentrant circuit. One group found false tendons in 15 of 15 patients undergoing catheter ablation for fascicular VT.13 Another reported cure of fascicular VT by surgical resection of a false tendon.14 However, when studied systematically, false tendons are equally prevalent among patients without fascicular VT, casting doubt as to whether false tendons truly are a specific substrate for fascicular VT.15 Left posterior fascicular VT has a right bundle left superior axis QRS morphology, similar to that of posteromedial papillary muscle VT; left anterior fascicular VT has a right bundle right inferior axis QRS morphology, similar to that of anterolateral papillary muscle VT. Several electrocardiographic characteristics are useful in differentiating fascicular VT from papillary muscle VT. Fascicular VT has a typical right bundle branch block pattern in lead V1, with an rSR′ configuration. In contrast, papillary muscle VT most commonly has a qR pattern in V1 or, less commonly, a monophasic R wave.16 The QRS duration tends to be shorter in fascicular VT than in papillary muscle VT (mean QRS 130 milliseconds vs. 150 milliseconds).16,17 Lastly, left posterior fascicular VT has q waves in leads 1 and aVL, likely reflective of early left-to-right septal activation, with the exit site directly on the septum as opposed to on the papillary muscle (Figure 82-2).17 During ablation, we have found intracardiac echocardiography to be valuable in defining catheter position relative to the papillary muscle (Figure 82-3). Figure 82-2 Electrocardiographic Characteristics of Fascicular and Papillary Muscle Ventricular Tachycardia Intravenous verapamil acutely terminates or slows fascicular VT in most patients, so much so that fascicular VT is also referred to as verapamil-sensitive left ventricular tachycardia.18–21 No effect is typically seen with adenosine. Although data regarding long-term treatment with oral verapamil are sparse, many patients do experience improvement in symptoms.22 Response to β-blockers and potassium channel blockers has also been described, and experience with sodium channel blockers has been limited but not encouraging.23 In contrast, focal Purkinje VT responds best to β-blockers and sodium channel blockers.24 The long-term results of catheter ablation for fascicular VT are excellent, with success rates greater than 90%.5,7,25,26 Thus ablation is appropriate for those with severe symptoms, those failing treatment with antiarrhythmic medications, and those intolerant to antiarrhythmic medications. Different strategies for ablation during VT have been reported. Some advocate targeting the abnormal, slowly conducting Purkinje/adjacent ventricular tissue, which forms the diastolic limb of the VT circuit, preceding the QRS complex by 40 to 110 milliseconds.7,27 As one moves apically along the left posterior or anterior fascicle, the diastolic potentials becomes less early (see Figure 82-1, DP in top right). Others advocate targeting the left posterior fascicle itself, which is the systolic limb of the VT circuit. During VT, they ablate the earliest Purkinje potential along the apical half of the inferoseptum, typically preceding the QRS complex by 15 to 40 milliseconds at successful sites (see Figure 82-1, LPS in top right).5 These sites will also record Purkinje potentials in sinus rhythm, after the His recording and before the QRS (see Figure 82-1, LPF in top left). Although transection of the left posterior fascicle at any point along its length should be sufficient to abolish the VT circuit, targeting midway from the base to the apex is advisable, as ablation that is too basal may cause left bundle branch block or complete heart block, and ablation that is too apical may be ineffective as the left posterior fascicle arborizes.

Fascicular Ventricular Arrhythmias

Fascicular Ventricular Tachycardia

Clinical Presentation

Mechanisms

During sinus rhythm (left), anterograde conduction occurs over the left posterior fascicle (LPF), as well as in abnormal, decremental Purkinje tissue (DP). The activation wave front also proceeds retrograde over the DP, resulting in a collision within the DP. During fascicular VT (right), retrograde conduction occurs over the LPF, with anterograde conduction over the DP. (Adapted from Maruyama M, Tadera T, Miyamoto S, Ino T: Demonstration of the reentrant circuit of verapamil-sensitive idiopathic left ventricular tachycardia: Direct evidence for macroreentry as the underlying mechanism. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 12:968-972, 2001; Nogami A, Naito S, Tada H, et al: Demonstration of diastolic and presystolic Purkinje potentials as critical potentials in a macroreentry circuit of verapamil-sensitive idiopathic left ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol 36:811-823, 2000; and Aiba T, Suyama K, Aihara N, et al: The role of Purkinje and pre-Purkinje potentials in the reentrant circuit of verapamil-sensitive idiopathic LV tachycardia. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 24:333-344, 2001.)

Substrate

Electrocardiographic Characteristics

Representative 12-lead electrocardiograms are provided for left posterior fascicular ventricular tachycardia (VT) and posteromedial papillary muscle VT. Red stars indicate initial q waves in leads 1 and aVL for fascicular VT, which are not present for PM VT. Blue stars indicate a qR pattern or a monophasic R wave in lead V1, which is present for papillary muscle VT, but not for fascicular VT.

Treatment

Medications

Catheter Ablation

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Fascicular Ventricular Arrhythmias