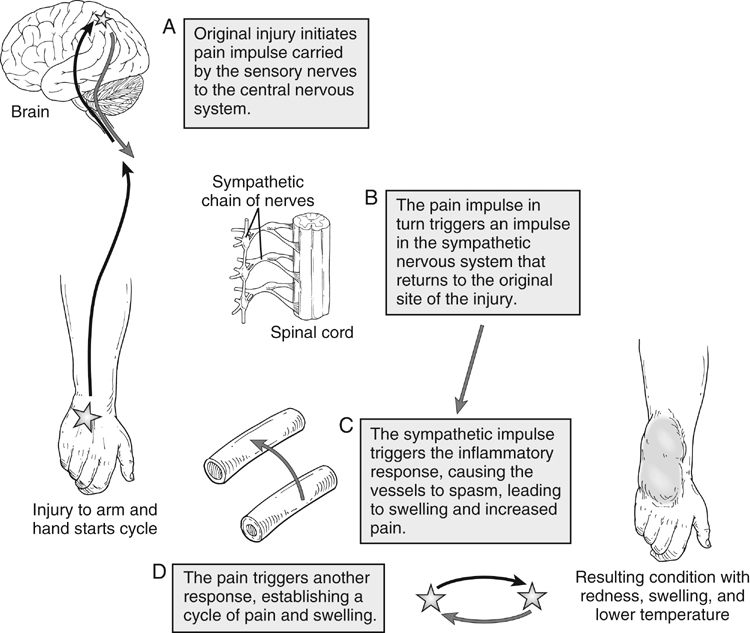

The development of RSD is poorly understood, but it is related to sympathetic nerve dysfunction and involves three nervous system mechanisms (Figure 1): The pathophysiology of RSD results in the signs of mottled skin, muscle spasms, and joint immobility, but the primary compliant is a disabling burning pain in the extremity. This CPRS condition can develop in children and adults and has no apparent no gender predisposition. Its development is associated with a variety of events, with the common denominator being extremity injury (Box 1). Young (15-30 yr), active adults appear to be the most prone to RSD, which develops when extremity injury does not follow the normal path of healing. Development does not depend on the magnitude of injury, and initial diagnosis can be hampered by the lack of physical findings in the setting of severe extremity pain. Joint sprains and repetitive motion disorders, such as carpal tunnel syndrome, can produce RSD and result in accusations of malingering if the inciting event was work related. In 1959, Drucker and colleagues characterized three clinical stages of RSD with the progression of symptoms and disability occurring in an unpredictable manner with time (Box 2). In stage I RSD, extremity pain is localized to the region of injury but with pain increasing during the healing process. Extremity tenderness and sensitivity to normal touch or motion is out of proportion to what is expected based on objective signs (contusion, fracture, surgical site healing). The pain is described as constant, with features of a burning sensation or a deep ache. Any repetitive tactile contact escalates pain severity (allodynia) and causes the pain to persist for an extended time period (hyperpathia). Palpation of skin trigger points as seen with other myofascial pain syndromes can often be elucidated on questioning the patient or performing physical examination. Evaluating the patient by sympathetic block is both diagnostic and therapeutic, because the clinical course of acute RSD may be reversible, and regional sympathetic block can provide pain relief well beyond the normal duration of the local anesthetic drug used.

Extremity Causalgia

Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy

Increased afferent impulses from peripheral nerves after injury caused by increased sensitivity to norepinephrine released by sympathetic postganglionic neurons

Increased afferent impulses from peripheral nerves after injury caused by increased sensitivity to norepinephrine released by sympathetic postganglionic neurons

Regenerating primary afferents from artificial synapses with regenerating sympathetic neurons

Regenerating primary afferents from artificial synapses with regenerating sympathetic neurons

Increased stimulation in the internuncial pool located in the anterior horn of the spinal cord, with gate-opening transmission of peripheral nerve impulses to the brain resulting in increased pain perception

Increased stimulation in the internuncial pool located in the anterior horn of the spinal cord, with gate-opening transmission of peripheral nerve impulses to the brain resulting in increased pain perception

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree