Extended Resection for Esophageal Carcinoma

Jeffrey L. Port

Paul Lee

Nasser K. Altorki

Worldwide, esophageal carcinoma is the sixth most common cause of cancer deaths. In the United States, a 350% increase in incidence has occurred over the past two decades. It is therefore particularly alarming that the treatment for this disease remains a formidable challenge, with an overall survival of only 15%.9,25,26 Despite the increasingly common addition of chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy to the treatment paradigm, surgical resection remains an essential component for the treatment of localized esophageal carcinoma. However, there is ongoing controversy regarding the preferred surgical strategy, which relates mainly to the surgical approach (trans- hiatal or transthoracic) and the extent of lymphadenectomy (Table 137-1). Most surgeons regard esophageal cancer as a systemic disease at the time of diagnosis, with palliation being the essential surgical objective. Surgical practice influenced by this view limits nodal clearance to easily accessible periesophageal and perigastric lymph nodes. In this paradigm, surgical cure may be only a random phenomenon. Not surprisingly, overall, 5-year survival has remained in the 15% to 20% range with or without preoperative therapy.

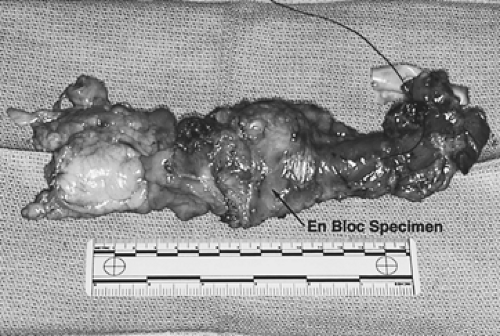

A few surgical groups have advocated more extended resections for esophageal carcinoma. En bloc esophagectomy involves resection of the esophagus within a wide envelope of adjoining mediastinal tissue accompanied by a thorough dissection of the mediastinal and upper abdominal retroperitoneal lymph nodes (two-field dissection). More recently, further extension of the operations included dissection of lymph nodes in the superior mediastinum and lower neck (three-field dissection) in an attempt to eliminate known or occult locoregional disease. The objective of these extended resections is to improve disease control and thus possibly enhance survival. Although the 5-year survival after these extended resections is encouraging, they remain controversial in most of western Europe and the United States.3

Preoperative Evaluation

Preoperative evaluation should be aimed at establishing the histologic diagnosis, determining the extent of local and distant disease, and evaluating the patient’s physiologic status. Radiologic evaluation should include an upper gastrointestinal series and a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen. A barium swallow will document the location and length of the lesion and should include the stomach and duodenum. A CT scan will establish the local extent of the tumor, including mural penetration and infiltration into adjacent tissues, and may suggest nodal involvement or, more importantly, distant metastases. Endoscopy should be performed, preferably by the operating surgeon. During endoscopy, attention should be directed to identifying the relationship of the tumor to the cricopharyngeus, the squamocolumnar junction, and the diaphragmatic hiatus. It is also important to note the presence and extent of Barrett’s esophagus and the presence of satellite lesions. This information is invaluable and may affect the extent and approach for esophagectomy. Most patients will also undergo both an endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and positron emission tomography (PET) scan. EUS has been established as an invaluable tool in evaluating the depth of tumor penetration and involvement of regional lymph nodes; it should be utilized in patients being considered for neoadjuvant therapy. Lightdale13 reports that EUS appears to have a diagnostic accuracy of 80% in predicting the T status and a 70% accuracy in predicting the N status. Also, transesophageal needle aspiration of periesophageal or perigastric nodes can often be performed with ultrasound guidance. PET scanning appears to add further sensitivity for the detection of distant visceral and skeletal metastases.16 Furthermore, recent reports have suggested that PET scanning may play a role in assessing response following induction therapy.23

Bronchoscopy is critical in evaluating tumors of the upper and middle third as well as assessing vocal cord function and major airway involvement. Finally, thoracoscopy and lap- aroscopy have recently been reported as staging modalities for esophageal cancer. These techniques offer the potential to assess the extent of lymph node involvement, identify serosal and peritoneal implants, identify liver metastases, and, perhaps most importantly, detect T4 disease. Krasna11 reported a 93% staging accuracy using thoracoscopic and laparoscopic techniques for staging esophageal carcinomas. Overall, the data suggest that minimally invasive surgical techniques may provide some added benefit to conventional studies in assessing esophageal carcinoma.

Generally, patients are considered for primary surgical resection if preoperative evaluation revealed no evidence of distant

visceral metastases or clear evidence of direct neoplastic invasion of the airway or major vascular structures. The presence of extensive nodal disease is not considered a contraindication to extended resection unless it clearly extends beyond the proposed fields of dissection.

visceral metastases or clear evidence of direct neoplastic invasion of the airway or major vascular structures. The presence of extensive nodal disease is not considered a contraindication to extended resection unless it clearly extends beyond the proposed fields of dissection.

Table 137-1 Types of Esophageal Resection | |

|---|---|

|

All patients with esophageal cancer must undergo a careful assessment of their pulmonary and cardiac status prior to resection. Many of these patients, when questioned, are current smokers who must be counseled to abstain from tobacco for at least 2 weeks prior to resection. The length of the procedure and high incidence of complications necessitate that elective surgery be performed only when comorbidities have been optimally managed. As reported by Marmuse and Maillochaud,15 the majority of patients undergoing esophagectomy have coexisting pulmonary and cardiac disease; for this reason, pulmonary function tests and cardiac stress studies are often obtained.

Management of Anesthesia

Patients undergoing a transthoracic esophagectomy should have an epidural catheter placed for postoperative pain control. In addition, a double-lumen endotracheal tube will allow for single-lung ventilation and greatly enhance the exposure. A radial artery catheter for continuous blood pressure monitoring is recommended. Two large-bore peripheral intravenous catheters should be inserted and urinary output monitored with a Foley catheter.

En bloc Resection

The deep location of the esophagus within the narrow confines of the mediastinum and the lack of a well-defined mesentery have generally precluded the application of en bloc resection to patients with esophageal carcinoma. In 1963, Logan reported on 250 patients with cancer of the cardia who underwent en bloc resection.14 While the operative mortality was high, the 5-year survival that was achieved was unparalleled at the time. Skinner resurrected that approach in 1979 and extended its use to tumors of the middle and lower esophagus, publishing his first approach in 1983.24

The basic principle underlying the operation is resection of the tumor-bearing esophagus within a wide envelope of adjoining periesophageal tissue that includes both pleural surfaces laterally and the pericardium anteriorly (Fig. 137-1). The lymphatics between the esophagus and aorta, including the thoracic duct, are resected en bloc with the esophagus along with the surrounding mediastinal lymph nodes from the tracheal bifurcation to the hiatus. An upper abdominal lymphadenectomy is also performed, including the common hepatic, celiac, left gastric, lesser curvature, parahiatal, and retroperitoneal nodes (Fig. 137-2). A third-field nodal dissection can be incorporated by extending the lymphadenectomy to include the superior mediastinal and cervical lymph nodes (Fig. 137-3). The procedure is almost always carried out through three incisions: a right thoracotomy followed by a laparotomy and collar neck incision.

The Thoracic Phase

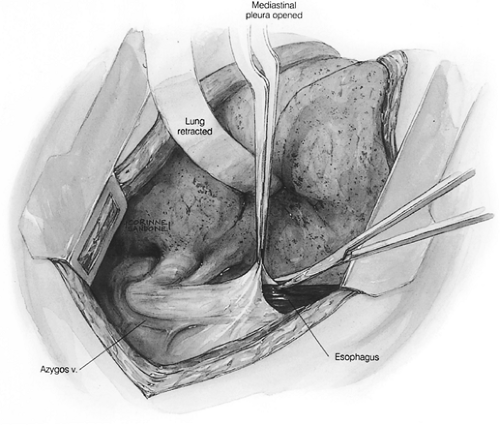

A right thoracotomy through the fifth interspace is performed. The first field comprises the middle and lower mediastinum and is bound superiorly by the tracheal bifurcation, inferiorly by the esophageal hiatus, anteriorly by the hilum of the lung and pericardium, and posteriorly by the descending thoracic aorta and the spine. The dissection begins by incising the pleura just anterior to the main trunk of the azygos vein throughout its course.

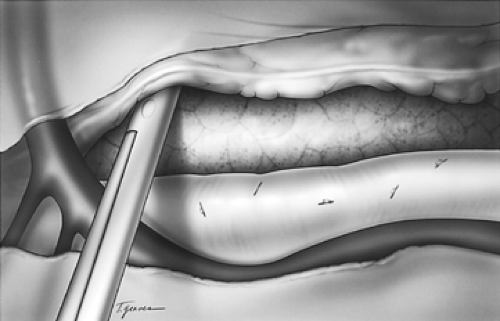

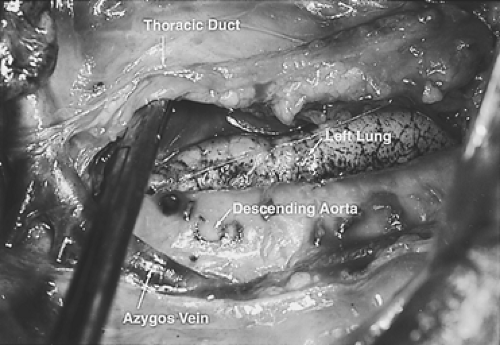

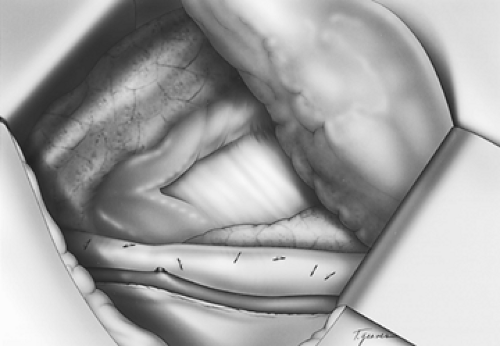

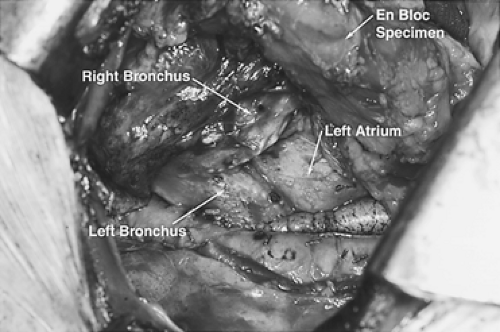

The dissection proceeds leftward toward the aortic adventitia, thus mobilizing the thoracic duct throughout its course in the lower and middle mediastinum (Figs. 137-4 and 137-5). The duct is ligated proximally at the aortic hiatus and distally as it crosses to the left side at the level of the aortic arch. The trunk of the azygos vein and the intercostal vessels are preserved. Dissection continues anterior to the aorta toward the left pleura, which is incised from the level of the left main bronchus to the diaphragm (Figs. 137-6 and 137-7). This completes the posterior mediastinectomy. The anterior dissection begins by division of the azygos vein at its caval junction. Dissection then proceeds along the back of the hilum of the right lung, sweeping all lymphatic tissues, including the subcarinal nodal chain, toward the specimen. A patch of pericardium is excised en bloc with the specimen where the tumor-bearing esophagus abuts the pericardium. The right inferior pulmonary ligament is incised close to the lung and the esophagus is lifted out of its mediastinal bed, exposing its attachment to the contralateral pulmonary ligament, which is divided, thus completing the esophageal mobilization. In tumors that transverse the hiatus, a cuff of diaphragm is circumferentially excised around the esophagus. Above the

carina, the esophagus is separated from its prevertebral and retrotracheal attachments and dissected well into the neck. The completed dissection clears all nodal tissue in the middle and lower mediastinum, including the right and left paraesophageal, parahiatal, para-aortic, subcarinal, bilateral hilar, and aortopulmonary lymph nodes. The specimen is left in situ and the chest is closed with pleural drainage.

The dissection proceeds leftward toward the aortic adventitia, thus mobilizing the thoracic duct throughout its course in the lower and middle mediastinum (Figs. 137-4 and 137-5). The duct is ligated proximally at the aortic hiatus and distally as it crosses to the left side at the level of the aortic arch. The trunk of the azygos vein and the intercostal vessels are preserved. Dissection continues anterior to the aorta toward the left pleura, which is incised from the level of the left main bronchus to the diaphragm (Figs. 137-6 and 137-7). This completes the posterior mediastinectomy. The anterior dissection begins by division of the azygos vein at its caval junction. Dissection then proceeds along the back of the hilum of the right lung, sweeping all lymphatic tissues, including the subcarinal nodal chain, toward the specimen. A patch of pericardium is excised en bloc with the specimen where the tumor-bearing esophagus abuts the pericardium. The right inferior pulmonary ligament is incised close to the lung and the esophagus is lifted out of its mediastinal bed, exposing its attachment to the contralateral pulmonary ligament, which is divided, thus completing the esophageal mobilization. In tumors that transverse the hiatus, a cuff of diaphragm is circumferentially excised around the esophagus. Above the

carina, the esophagus is separated from its prevertebral and retrotracheal attachments and dissected well into the neck. The completed dissection clears all nodal tissue in the middle and lower mediastinum, including the right and left paraesophageal, parahiatal, para-aortic, subcarinal, bilateral hilar, and aortopulmonary lymph nodes. The specimen is left in situ and the chest is closed with pleural drainage.

The Abdominal Phase

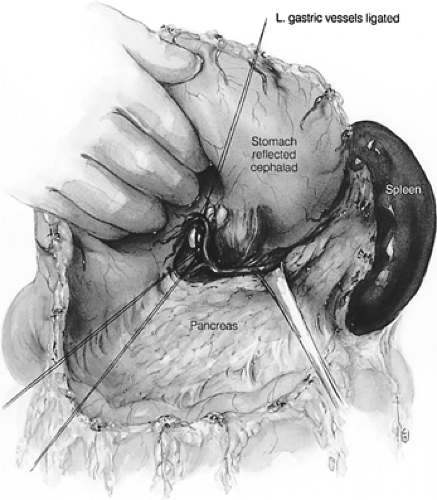

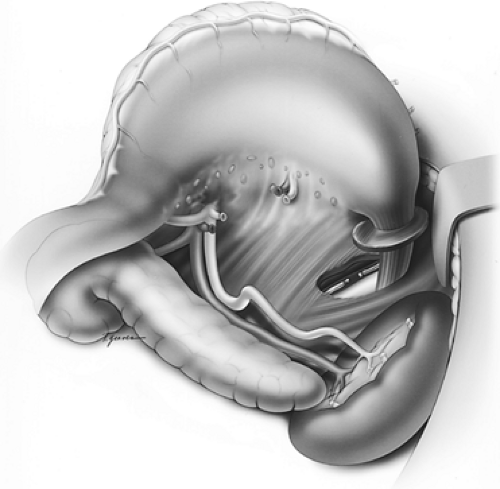

The patient is repositioned for a simultaneous laparotomy and cervical incision. An upper midline incision is created. Full abdominal exploration ensues, with special attention to evidence of tumor dissemination in the form of peritoneal and serosal implants and liver metastases. An abdominal self-retaining retractor such as the Omni-Tract (St. Paul, MN) is useful. The omentum is dissected off of the transverse colon and transected several centimeters from the gastroepiploic arcade; the lesser sac is then entered. Following division of the short gastric vessels, the retroperitoneum is incised along the superior border of the pancreas. The retroperitoneal lymphatic and areolar tissues are swept superiorly toward the esophageal hiatus and medially along the splenic artery to the celiac trifurcation. The left gastric artery is divided flush with its celiac origin and the nodes along the common hepatic artery are dissected toward the specimen. This retroperitoneal dissection is bound by the dissected esophageal hiatus superiorly, the hilum of the spleen laterally, and the common hepatic artery and inferior vena cava medially (Fig. 137-8). Finally, the lesser curvature and left gastric nodes are included with the specimen as the gastric tube is prepared.

The Cervical Phase

A low collar incision is performed and subplatysmal flaps are raised inferiorly and superiorly (Fig. 137-9). The prevertebral space is entered medial to the carotid sheath, and the esophagus (previously fully mobilized from the thorax) is retrieved.

The esophagus is divided and the specimen is retrieved in the abdomen. The stomach is transected from the fundus to the third or fourth branch of the left gastric artery. This preserves a full length of stomach for advancement into the neck. A pyloromyotomy is always performed. The gastric tube is advanced through the posterior mediastinum to the neck (Fig. 137-10). The anastomosis is hand sewn using a single-layer running technique with a monofilament absorbable suture. More recently, the authors have performed a hybrid stapled anastomosis, as described by Orringer.20 Any redundant stomach is retracted into the abdomen and the gastric tube is secured to the hiatus with care not to injure the gastroepiploic arcade. A feeding jejunostomy tube is routinely placed for early postoperative enteral feeding.

The esophagus is divided and the specimen is retrieved in the abdomen. The stomach is transected from the fundus to the third or fourth branch of the left gastric artery. This preserves a full length of stomach for advancement into the neck. A pyloromyotomy is always performed. The gastric tube is advanced through the posterior mediastinum to the neck (Fig. 137-10). The anastomosis is hand sewn using a single-layer running technique with a monofilament absorbable suture. More recently, the authors have performed a hybrid stapled anastomosis, as described by Orringer.20 Any redundant stomach is retracted into the abdomen and the gastric tube is secured to the hiatus with care not to injure the gastroepiploic arcade. A feeding jejunostomy tube is routinely placed for early postoperative enteral feeding.

Figure 137-8. Illustration of the intraperitoneal en bloc dissection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|