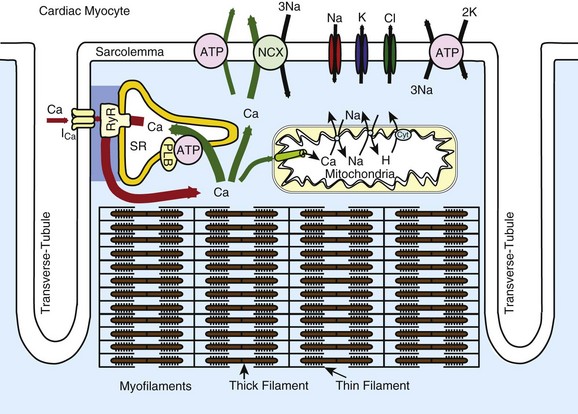

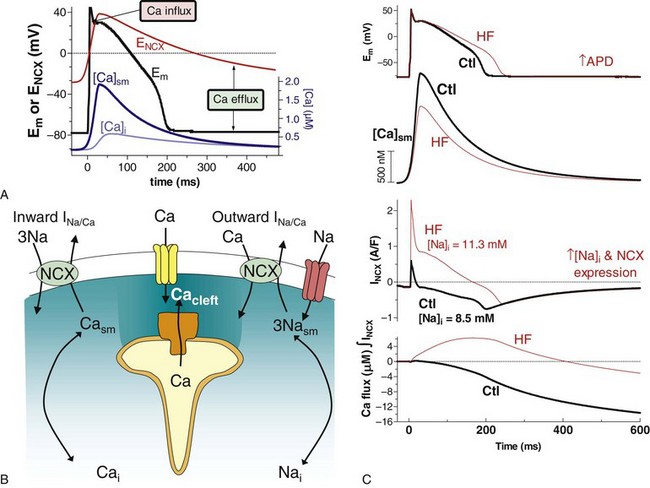

16 Excitation-Contraction Coupling and Relationship to Action Potentials Sources and Sinks of Ca in Myocytes: Sarcolemma, Sarcoplasmic Reticulum, Mitochondria Balance of Fluxes, E-C Coupling Gain, and Fractional Ca Release Structure of the Couplon and Submembrane Spaces E-C Coupling: Ca-Induced Ca Release, Ca Sparks, and Ca Waves Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling (ECC) refers to the process by which the electrical activation of cardiac myocytes leads to the activation of contraction.1–3 In its broadest use, ECC refers to everything from the initial membrane depolarization through the action potential (AP) and activation of the Ca transient, including how the myofilaments respond to the Ca transient to produce contraction. This chapter will focus on the initiation of normal and abnormal Ca transients in myocytes, Ca transport and buffering mechanisms, and the interaction of Ca signaling with the AP, arrhythmias, and gene regulation. In recent years, it has become increasingly clear that Ca signaling and cardiac electrophysiology are inextricably interrelated, making it essential to understand myocyte Ca regulation to understand arrhythmogenesis. Figure 16-1 shows the structure and key mediators of ECC in myocytes. Ca influx via Ca current (ICa) and Ca release from the ryanodine receptor (RyR) in the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) are central to myofilament activation. Ventricular myocytes have a network of transverse or T-tubules that dive into the cell center, perpendicular to the long axis of the myocyte. This T-tubular system also exhibits longitudinal extension in some myocytes. The role of the T-tubular system is to synchronize the sarcolemmal electrical signal (AP) at junctions throughout the cell, where the plasma membrane and SR are close together and mediate Ca-induced Ca release. In heart failure (HF), there is evidence that the T-tubule network is less extensive and less well organized,4,5 which can reduce efficacy of the overall ECC process. Figure 16-1 Schematic of Ca handling systems in cardiac myocytes. Ca2+, Na+, K+, and Cl− channels are shown, as are sarcolemmal and SR ATPase pumps (ATP). The SR Ca-ATPase is inhibited by phospholamban (PLB), whose inhibitory effect is reversed by phosphorylation by protein kinase A or Ca-calmodulin–dependent protein kinase. The mitochondrial cytochrome system (Cyt) responsible for pumping protons (H) out of mitochondria is indicated. Atrial myocytes have fewer T-tubules,5 and specialized conduction fibers (sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes and Purkinje fibers) have almost no T-tubules. In cells or regions thereof that lack T-tubules, ICa initiates SR Ca release only at the surface membrane junctions. Then depending on the conditions discussed later, activation can more slowly propagate as a wave of Ca-induced Ca release to the center of the myocyte (via a chain of RyR clusters) or fail to propagate such that the surface release produces only a small and slow [Ca] elevation near the center of the cell. It is this rise in intracellular [Ca] ([Ca]i) that activates the myofilaments to contract. Ca binds to troponin C on the thin filaments, which induces a conformational change that allows the heads of myosin molecules that stick out along the thick filament to bind to actin molecules, which form the body of the thin filament (see Figure 16-1). The myosin head uses energy stored in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to tilt the head (pulling on the actin filament), thus creating force or sarcomere shortening, which is responsible for isovolumic contraction and ejection of blood from the heart. The synchronization of local Ca transients throughout the heart is therefore essential for synchronous ventricular contraction. The strength of contraction is directly related to the [Ca] surrounding the myofilaments. Thus a myocyte (or region thereof) that has a small Ca transient will be weaker than an adjacent area and can damp the strength of the stronger region (i.e., the strong cell can expend its strength, stretching a weak neighbor, and thus not contribute to cardiac output). Readily appreciable consequences of this mechanical dyssynchrony include ischemia ventricular fibrillation and spatially discordant cardiac alternans. During the AP, voltage-dependent Ca channels open and allow Ca entry down its electrochemical gradient, causing an inward depolarizing current (see Chapter 2 for Ca-channel gating details). In ventricular myocytes, the ICa is virtually all mediated by L-type Ca channels (LTCC), in particular by the Cav1.2 isoform. Atrial, and especially pacemaker, cells also express the Cav1.3 LTCC isoform, which activates at a more negative Em, and thus can better contribute to phase 4 depolarization in pacemakers and recruit additional Cav1.2 channels. ICa is activated by depolarization and exhibits Em– and Ca-dependent inactivation (VDI and CDI), and CDI is by far the dominant physiologic mode of inactivation.6 When CDI is abrogated experimentally, AP duration (APD) becomes extremely long and Ca tends to overload in cells. There appears to be calmodulin (CaM) constitutively bound to the Cav1.2 in myocytes and it senses local [Ca]i elevation and induces inactivation.7 Although Ca entry via the channel itself can contribute to CDI, most LTCCs in cardiac myocytes are localized at junctions with the SR and RyR, and the Ca-induced Ca release is even more powerful in causing CDI. The integrated amount of Ca influx via ICa in ventricular myocytes during a normal AP is 5 to 10 µmol/L cytosol but is about twice as large if SR Ca release is blocked. In context, in this Ca flux the amount of SR Ca release in mammalian ventricular myocytes is normally three to ten times larger than this, depending on species and conditions. The regulation of SR Ca release will be discussed in more detail. NCX can also contribute to the rise in [Ca]i, but Ca entry via NCX is normally small (<1 µmol/L cytosol) and constrained largely to the very early part of the AP. NCX can bring Ca in or out (outward or inward current) during the AP, depending on the trans-sarcolemmal [Na] and [Ca] gradients and Em (Figure 16-2). During diastole, the Em is negative to the electrophysiologic reverse potential for NCX (ENCX = 3ENa − 2ECa), so Ca efflux is thermodynamically favored (see Figure 16-2, A). However, the low diastolic [Ca]i kinetically limits the amount of transport (low substrate concentration). The peak of the AP exceeds ENCX and briefly favors Ca influx (an outward current). However, as soon as ICa and SR Ca release begin, the local [Ca]i in the cleft and submembrane space ([Ca]sm) is much higher than [Ca]i and drives Ca extrusion via NCX (see Figure 16-2, B and C). The declining Em during repolarization also more strongly favors Ca efflux, and that persists throughout [Ca]i decline and diastole (see Figure 16-2, A). Thus, NCX is mainly considered a Ca efflux mechanism. An exception to this is certain pathophysiologic conditions like HF, in which [Na]i is elevated, NCX expression may be elevated, Ca transients are small, and APD is prolonged (see Figure 16-2, C). All these factors shift NCX more in favor of Ca influx, and thus in HF, Ca entry via NCX can persist for most of the AP plateau and significantly contribute to the Ca transient. In a sense, this limits the extent of cardiac dysfunction in HF by bringing Ca in and by indirectly helping load the SR with Ca. Figure 16-2 Na/Ca exchange (NCX) function in cardiac myocytes. A, Normal rabbit ventricular myocyte AP (black), global and submembrane Ca transients ([Ca]i and [Ca]sm, blue), and the reversal potential for NCX (red) based on [Ca]sm and with [Na]i −8.5 mM. Ca influx is favored only early in the AP (where Em is higher than ENCX). B, During SR Ca release, cleft and submembrane [Ca] (Cacleft and Casm) are higher than bulk cytosolic [Ca]i. This influences whether INCX is inward or outward. C, INCX during the rabbit ventricular myocyte during the AP in control and HF conditions. [Ca]sm and the integrated Ca flux via NCX are also shown. (Redrawn from Despa S, Islam M, Weber CR, et al. Intracellular Na+ concentration is elevated in heart failure, but Na/K pump function is unchanged. Circulation 105:2543–2548, 2002.) There are four transporters that work in parallel to bring [Ca]i down and drive relaxation: (1) the SR Ca-ATPase, (2) NCX, (3) the plasma membrane Ca-ATPase, and (4) mitochondrial Ca uptake.1,2 We have analyzed quantitatively how these processes compete in myocytes from different mammalian species. In rabbit (and similarly in human, canine, feline, ferret, and guinea pig), the percent contribution to [Ca]i decline is roughly 70%, 28%, 1%, and 1%, respectively. Thus, the SR Ca-ATPase is the dominant transporter by a factor of 3 over the NCX. In rat and mouse ventricular myocytes, these numbers are 92%, 7%, 0.5%, and 0.5%, so the system is much more SR-dominated (14-fold more than NCX). In HF, there is generally a downregulation of SR Ca-ATPase and upregulation of NCX, such that in rabbit and human HF, the SR and sarcolemmal fluxes become more equally balanced. There are fewer data available in atrial myocytes, but for human atrial myocytes, we estimate 66% and 25% of Ca removal occur via SR Ca-ATPase and NCX, respectively. This predominance of SR Ca-ATPase over NCX in sinus rhythm is converted to an equal contribution of these Ca-removal processes (46% vs. 44%) in chronic atrial fibrillation.8,9 In mitochondria, there is uptake of Ca during the normal heartbeat via the mitochondrial Ca uniporter,10 but it can be inferred that this is only about 0.5 µmol/L cytosol (~1 µmol/L mitochondria). Significant Ca buffering is expected in this compartment, which is packed with proteins (as in the cytosol), so the rise in free [Ca] in the mitochondria at each beat is rather small.11 The extrusion of Ca from mitochondria is mediated mainly by a mitochondrial Na/Ca exchanger (NCLX),12 which is different from the sarcolemmal NCX. This Ca extrusion is very slow, such that at higher heart rates, the diastolic mitochondrial [Ca] gradually accumulates to a higher steady-state level. One important effect of increased mitochondrial [Ca] is that it binds to and stimulates several dehydrogenase enzymes in the mitochondria to increase the production of NADH and consequently increases ATP production.3 This is thought to be an important feedback pathway, where the mitochondria increase their ATP production under conditions in which the myocyte is using more ATP (i.e., when Ca transients are more frequent and/or of higher amplitude). When heart rate is reduced, the diastolic Ca efflux has a better opportunity to keep up with the less frequent influx pulses, and mitochondrial [Ca] gradually falls. Under severe cellular stress, mitochondria can store large amounts of Ca, in part by progressively increasing their buffering power.13 This is thought to provide temporary protection in the myocyte from the dangers of Ca overload. However, too much Ca in mitochondria can lead to opening of the permeability transition pore and loss of proteins, which can lead to mitochondrial demise.

Excitation-Contraction Coupling

Excitation-Contraction Coupling and Relationship to Action Potentials

Sources and Sinks of Ca in Myocytes: Sarcolemma, Sarcoplasmic Reticulum, Mitochondria

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree