Excision of Esophageal Diverticula

Philip A. Rascoe

W. Roy Smythe

Diverticula of the esophagus are uncommon disorders that are usually classified according to their location (cervical, thoracic, or epiphrenic), their pathogenesis (pulsion or traction), and their morphology (true or false).

The great majority of esophageal diverticula are acquired lesions that occur predominantly in elderly adults. Pulsion, or false, diverticula are the most commonly encountered type of esophageal diverticula. These localized outpouchings lack a muscular coat, and their wall is formed entirely by mucosa and submucosa. Almost all are the result of a functional obstruction to the advancing peristaltic wave, usually caused by an abnormal upper or lower esophageal sphincter. Occasionally, impedance to peristaltic progression may be the result of peptic strictures or localized motility disorders such as spasm. Pulsion diverticula thus occur most commonly at the level of the cricopharyngeus where there is a weak area of the crossing muscle fibers in Killian’s triangle or the distal 10 cm of the thoracic esophagus between the inferior pulmonary vein and the diaphragm (epiphrenic location); however, they may also occur within the midthoracic esophagus.

True, or traction, diverticula are usually seen in the middle one-third of the thoracic esophagus in a peribronchial location. These diverticula are the result of paraesophageal granulomatous mediastinal lymphadenitis secondary to disorders such as tuberculosis or histoplasmosis. The ensuing desmoplastic reaction tents the full thickness of the esophageal wall, producing a conical, wide-mouthed true diverticulum. They most frequently project to the right because subcarinal lymph nodes in this area are closely associated with the right anterior wall of the esophagus. These outpouchings are rarely seen in the Western world and are usually of little or no clinical significance except in rare instances when ongoing mediastinal inflammation results in a fistulous communication with the airway or other intrathoracic structures.

ZENKER’S DIVERTICULUM

The British surgeon Abraham Ludlow is credited with the original description of a pharyngoesophageal diverticulum from an autopsy specimen that remains on display at the Royal Infirmary Pathology Museum in Glasgow, Scotland. Almost a century later, the German pathologist Zenker provided a complete clinical and pathologic description of 34 cases. The pathogenesis of this lesion was first suggested in 1926 by Jackson, who proposed that the tonically contracting upper esophageal sphincter (UES) impeded the progress of the swallowed bolus. A localized increase in intraluminal pressure forces the mucosa to herniate through the posterior midline of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor in the anatomically bare area (Killian’s triangle) between the oblique fibers of the thyropharyngeus and the horizontal fibers of the cricopharyngeus. The diverticulum deviates away from the rigid vertebrae and usually presents on the left side. The exact nature of this cricopharyngeal motor dysfunction remains unclear, but most commonly an incomplete or incoordinated opening of the UES is present.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

CLINICAL PRESENTATIONZenker’s diverticulum is primarily a condition of the elderly and is twice as common in men. Dysphagia for solid food and regurgitation of undigested food are the most common symptoms and are typically present. Halitosis, noisy swallowing or “gurgling” after deglutition, and globus sensation are also common. Aspiration may also result from this condition, and it may manifest as a mild nocturnal cough, morning hoarseness, or new onset adult bronchospasm caused by repeated laryngeal penetration and irritation and, on rare occasion, present as chronic lower respiratory tract infection or even lung abscess. Despite the association among hiatal hernia, gastroesophageal reflux, and Zenker’s diverticulum, only a few patients present with severe heartburn and rarely do they require surgical correction of their reflux.

DIAGNOSIS

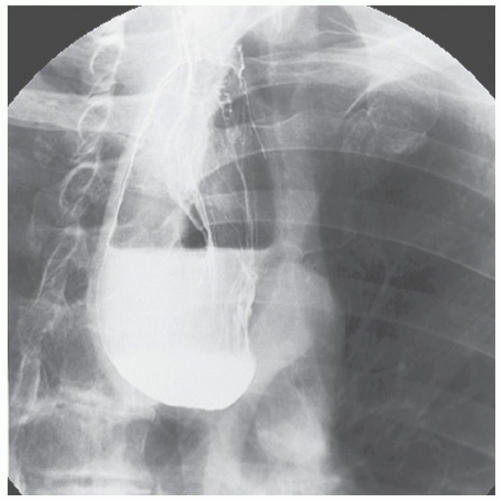

DIAGNOSISA barium esophagogram using a lateral or oblique projection usually demonstrates the diverticulum, which can be large and may protrude well into the superior mediastinum (Fig. 22.1). Esophageal manometry adds little information and should not be routinely performed. Endoscopy can be considered but often adds little to the diagnosis. Perforation of the diverticulum can result from aggressive endoscopic examination because the flexible endoscope often enters the diverticulum rather than the true esophageal lumen. Malignant change is possible but is exceedingly rare in these diverticula, with squamous cell carcinoma having been reported in no more than 0.5% of patients. If diverticulopexy is planned, the diverticulum should be carefully palpated to rule out a nodular density in the wall, and an intraoperative endoscopic examination can be performed to evaluate the interior of the sac as there will be no pathologic specimen.

TREATMENT

TREATMENTA small, completely asymptomatic diverticulum in an elderly patient with comorbidities that preclude general anesthesia likely can be safely observed. However, in most patients, once a diagnosis is made, treatment is suggested because these diverticula will often enlarge over time and can lead to the more bothersome complications such as aspiration. The gold standard for the surgical treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum is cricopharyngeal myotomy combined with either diverticulectomy or diverticulopexy via an open transcervical approach. However, advances in instrumentation for minimally invasive surgery now allow for

the management of Zenker’s diverticula via transoral endoscopic creation of a stapled esophagodiverticulostomy in many patients. This procedure utilizes a rigid diverticuloscope and an endoscopic GIA stapler to create a cricopharyngeal myotomy while bringing together the lumina of the pouch and esophagus. We believe that carefully selected patients may be offered endoscopic management with the caveat that conversion to an open procedure may be necessary should the minimally invasive approach prove technically unfeasible intraoperatively.

the management of Zenker’s diverticula via transoral endoscopic creation of a stapled esophagodiverticulostomy in many patients. This procedure utilizes a rigid diverticuloscope and an endoscopic GIA stapler to create a cricopharyngeal myotomy while bringing together the lumina of the pouch and esophagus. We believe that carefully selected patients may be offered endoscopic management with the caveat that conversion to an open procedure may be necessary should the minimally invasive approach prove technically unfeasible intraoperatively.

Endotherapy utilizing flexible endoscopes and various energy sources to divide the septum between the diverticulum and esophagus (which contains the cricopharyngeus muscle) has become more commonplace. These procedures are typically performed in an endoscopic unit by gastroenterologists. The purported benefits of this approach include the ability to perform the procedure without general anesthesia or neck extension. As only a 1.5- to 2-cm incision in the septum is recommended by most authors, diverticula >3 cm require longer incisions and, therefore, repeat procedures. A recent review of these procedures reports mediastinal emphysema from presumed microperforation in over 20% of patients and a clinical recurrence rate of approximately 20%. Given the exceptional results and minimal morbidity associated with both the traditional open repair and the transoral stapled procedure, we feel that these flexible endoscopic techniques should be reserved exclusively for poor operative candidates.

PREOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Endoscopic management may not be the preferred procedure in some patients due to anatomic constraints. Difficulty may be encountered in placing the diverticuloscope in patients with retrognathia, limited jaw mobility, prominent incisors, or rigid cervical kyphosis that limits neck extension. In a prospective study of factors predicting endoscopic exposure and repair of Zenker’s diverticulum, the endoscopic procedure was unsuccessful in 30% of patients. Patients with short necks, high body mass index (BMI), and decreased hyomental distance were less likely to have successful endoscopic repair, and the authors advocate an open approach in such patients. In addition, the size of the diverticulum on barium esophagogram should be assessed because small diverticula (<3 cm) are generally not amenable to stapling. A small pouch limits access of the stapler anvil and prohibits the attainment of an adequate length of myotomy. Diverticula >6 cm should also be managed with an open approach because endoscopic stapling results in a large pharyngeal cavity that does not empty completely. This information is helpful in preoperative discussions with the patient concerning the likelihood of conversion to an open procedure. All patients should be prepared and give consent for an open procedure in the event that endoscopic instrumentation proves unfeasible or a complication is encountered. Patients are instructed to limit their diet to clear liquids the day before surgery.

Although many cervical operative procedures may be performed under local anesthesia, general endotracheal anesthetic is suggested for this procedure, along with the usual preincision antibiotic prophylaxis.

ENDOSCOPIC SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

After induction of general anesthesia, a shoulder roll is placed to achieve neck extension in the standard position for rigid esophagoscopy. An upper jaw dental guard is placed. Direct endoscopy is performed using a lighted suspension laryngoscope. The esophageal lumen, diverticular lumen, and their common wall are visualized. The distal blades are opened slightly to enter the esophagus anteriorly and the diverticular lumen posteriorly. The distal blades of the instrument are opened, keeping the common wall between the esophagus and diverticulum centered in the scope’s aperture. The proximal scope is then widened, and the laryngoscope is attached to a suspension system to allow for bimanual instrumentation during the stapling procedure. A 0-degree bronchoscopic telescope attached to an endoscopic camera is then inserted laterally through the laryngoscope. The pouch is examined to exclude malignancy and to assess the depth of the pouch and length of the septum. A 30-mm linear GIA stapler is then introduced through the laryngoscope, and its jaws are positioned on the common wall with the longer end containing the staple cartilage within the esophageal lumen. The position of the jaws is confirmed using the telescope. If the position of the jaws is in question, the stapler is opened and the device reapplied. If necessary, traction sutures can be placed laterally in the common wall using an endosuture device and used to help pull the common wall into the jaws of the stapler. If proper positioning of the stapler cannot be confirmed before firing,

the minimally invasive approach cannot safely be performed and should be abandoned in favor of an open procedure. Once proper position is confirmed, the stapler is fired and removed. The stapler divides the common wall, including the cricopharyngeus muscle, between the diverticulum and esophagus and closes the wound edges with a triple row of staples on each side. The divided edges of the septum should retract laterally revealing an open esophageal lumen. The cut edges should be inspected to ensure hemostasis. Should a significant septum and diverticular sac still be present, a second stapler application should be performed in a similar manner. Once the septum is completely divided and hemostasis is confirmed, the procedure is terminated. Patients are offered a liquid diet the following day, and if fluids are tolerated, they are advanced to a soft diet and discharged on the second postoperative day. All patients should have a chest radiograph postoperatively to exclude perforation, which more than likely would manifest as air in the retropharyngeal space or mediastinum.

the minimally invasive approach cannot safely be performed and should be abandoned in favor of an open procedure. Once proper position is confirmed, the stapler is fired and removed. The stapler divides the common wall, including the cricopharyngeus muscle, between the diverticulum and esophagus and closes the wound edges with a triple row of staples on each side. The divided edges of the septum should retract laterally revealing an open esophageal lumen. The cut edges should be inspected to ensure hemostasis. Should a significant septum and diverticular sac still be present, a second stapler application should be performed in a similar manner. Once the septum is completely divided and hemostasis is confirmed, the procedure is terminated. Patients are offered a liquid diet the following day, and if fluids are tolerated, they are advanced to a soft diet and discharged on the second postoperative day. All patients should have a chest radiograph postoperatively to exclude perforation, which more than likely would manifest as air in the retropharyngeal space or mediastinum.

OPEN SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree