Three patients (2 women) 36, 45, and 49 years of age underwent cardiac transplantation for what was diagnosed clinically as nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Examination of the transthoracic echocardiogram and explanted heart in each disclosed marked hypertrabeculation involving the free wall of the very dilated left ventricle, a finding consistent with what has been termed “isolated ventricular noncompaction” (IVNC). Although these 3 cases anatomically fulfilled the echocardiographic definition of IVNC, review of previous publications containing gross photographs of the heart suggests that IVNC is overdiagnosed at least morphologically.

Although newborns with aortic valve atresia unassociated with mitral valve atresia have true sinusoids from the endocardium that burrow into the myocardium, the endocardium is smooth and devoid of trabeculations. Therefore, it is not proper in our view to consider the left ventricle in aortic valve atresia unassociated with mitral valve atresia an example of ventricular noncompaction as has been done. The first description of what later came to be termed “isolated ventricular noncompaction” (IVNC) in an adult was by Engberding and Bender who described a 33-year-old woman with heart failure, left bundle branch block, marked left ventricular dilatation, and echocardiographically demonstrated large trabeculations (called “sinusoids” by the investigators) within the left ventricular cavity. Subsequently, numerous reports have appeared describing—mainly by echocardiogram—features of IVNC. The present report describes morphologic features of hearts in 3 adults who underwent cardiac transplantation and the explanted hearts were characteristic of IVNC. In addition, previous published reports illustrating the heart at necropsy or after cardiac transplantation are reviewed to determine if IVNC is overdiagnosed at least morphologically.

Methods

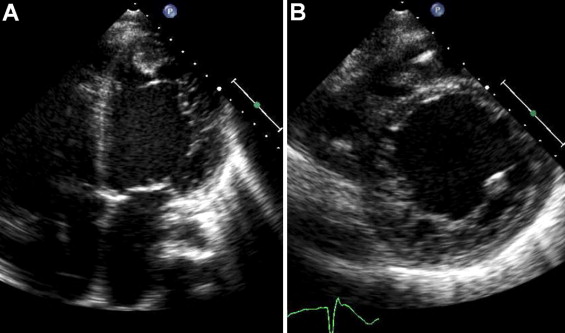

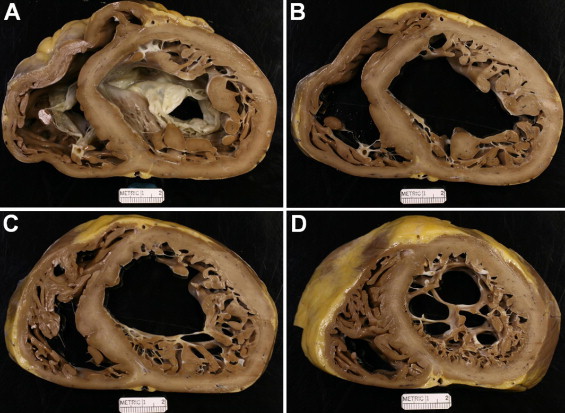

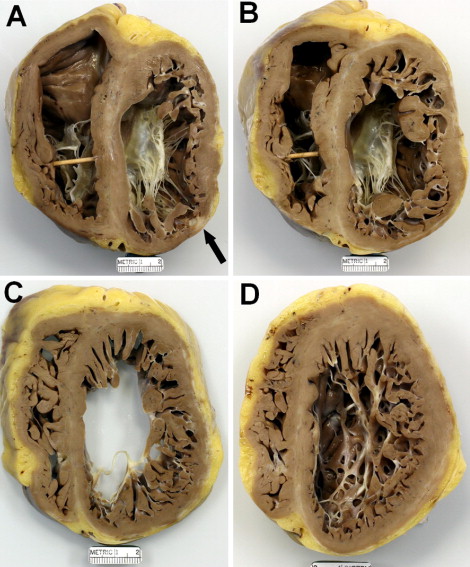

Pertinent clinical and morphologic features in each of the 3 patients are presented in Table 1 , and transthoracic echocardiographic and morphologic features are illustrated in Figures 1 through 6 . All 3 patients had evidence of chronic heart failure for 7, 10, and 12 years before cardiac transplantation at 36, 45, and 49 years of age, respectively. Three had episodes of ventricular tachycardia, and patient 2 had ventricular tachycardia ablation procedures on >1 occasion. All 3 had elevated pulmonary arterial pressures, low systemic arterial pressures, low cardiac indices, and very low left ventricular ejection fractions. All 3 by angiography had normal epicardial coronary arteries. None had a neuromuscular disorder. Examination of explanted hearts from all patients disclosed increased cardiac weight and hugely dilated left ventricular cavities with noncompacted portions of left ventricular free walls ≥2 times as thick as the compacted portions of these walls. Patient 1 had an organizing thrombus in the apex of the left ventricle. Patient 3 had an episode typical of transient ischemic attack. Patients 2 and 3 each had small transmural left ventricular free wall scars. Histologically, myofibers in each were hypertrophied, inflammatory cells were absent, and interstitial fibrous tissue was focally increased in the ventricular walls.

| Variable | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) at cardiac transplantation | 36 | 45 | 49 |

| Month and year of cardiac transplantation | October 2008 | March 2011 | May 2011 |

| Gender | Woman | Man | Woman |

| Age (years) at onset of signs and symptoms of cardiac dysfunction | 26 | 33 | 42 |

| Chronic heart failure | + | + | + |

| Atrial fibrillation | + | 0 | + |

| Ventricular tachycardia | + | + | + |

| Intracardiac pressures (mm Hg) | |||

| Mean pulmonary arterial wedge | 29 | 35 | 25 ⁎ |

| Pulmonary artery (peak systolic pressure/end-diastolic pressure) | 60/30 | 55/27 | 54/22 ⁎ |

| Right ventricle (peak systolic pressure/end-diastolic pressure) | 60/5 | 55/18 | 54/17 ⁎ |

| Right atrium (mean) | 14 | 8 | 14 ⁎ |

| Aorta (peak systolic pressure/end-diastolic pressure) | 90/60 † | 90/50 † | 100/80 ⁎ |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m 2 ) | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.0 ⁎ |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 10 | 15 | 5 |

| Automatic implantable cardioverter–defibrillator cardiac resynchronizing therapy | + | + | + |

| Left bundle branch block | + | + | 0 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 110 | 160 | 147 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 19.6 | 26.6 | 22.1 |

| Heart weight (g) | 420 | 530 | 360 |

| Maximal left ventricular cavity (cm) | 7.0 | 7.0 | 8.0 |

| Scar, left ventricular wall | 0 | + | + |

⁎ Recorded 14 months before heart transplantation.

Comments

Each of the 3 patients described had excessive ventricular trabeculations in very dilated left ventricles, bundle branch block, periodic ventricular tachycardia, severe heart failure, and finally cardiac transplantation.

What is IVNC in adults? Is it really a distinctive entity? Oechslin et al from Zurich described 34 adults with IVNC and stated that “… the characteristic discriminating feature … [of IVNC is a] … two layered myocardial wall structure with both a thin epicardial compacted zone and an extremely thickened endocardial non-compacted zone with deep recesses filled with blood from the ventricular cavity.” In 2006 alone, 3 reports described 61, 53, and 57 patients, respectively, >15 years of age with IVNC, each from separate single medical centers. In 2007 another 65 adults were reported, in 2008 another 60 adults were reported, and in 2010, 140 more adults were reported, each study from single medical centers. In addition, many other case studies and small series of patients have been described.

In the many publications on IVNC, most from Europe, we found 18 gross photographs of the heart in adults in peer-reviewed journals. Of these, in the view of 1 of the authors (W.C.R.), only 7 of the 18 cases represent clear examples of IVNC (hypertrabeculation). Burke et al were the only investigators to report and illustrate morphologically 2 adults with IVNC. One was an 18-year-old man who underwent cardiac transplantation for chronic heart failure. The second was a 30-year-old man who died suddenly and had a nondilated left ventricular cavity. (A beautiful example of IVNC was a heart prepared by Dr. William D. Edwards and published in an Up-to-Date piece in 2011 authored by Dr. H.M. Connolly and Dr. C.H.A. Jost.) The photograph shown of the heart in 1 report appears to be a classic example of cor pulmonale. Most published illustrated hearts were opened when fresh by cuts according to the flow of blood. These cuts result in flattened cardiac chambers and then comparison of the thickness of the compacted to that of the noncompacted portions of the cardiac ventricles is more difficult to discern. Cuts of the ventricles made parallel to the posterior atrioventricular sulcus after fixation appears to provide the best opportunity of demonstrating ventricular hypertrabeculation if present.

In Table 2 we attempt to show various characteristics of patients with 4 different types of cardiomyopathies. The various clinical features of IVNC and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy are virtually identical. Clearly, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is the most distinctive. Whether IVNC deserves a special characterization is debatable.