Evaluation of Results of Thymectomy for Nonthymomatous Myasthenia Gravis

Joshua R. Sonett

Alfred Jaretzki III

The role of thymectomy in the treatment of myasthenia gravis (MG) continues to generate significant debate regarding the differing surgical approaches to thymectomy, as well as the role and efficacy of thymectomy itself in the treatment of MG. To understand the controversies concerning the results of thymectomy for nonthymomatous MG, five basic issues need to be addressed. First, and of paramount importance, the reader must have an understanding of evidence-based information for proper evaluation of clinical research reports. Second, surgical arguments must be understood in the context that the benefit and efficacy of thymectomy itself in the treatment of nonthymomatous MG has not been definitively proven and is not universally recommended. Third, before the report of the Myasthenia Gravis Task Force by Jaretzki and colleagues in 2000,22,23 there had been no uniform criteria to define MG or measure the response to therapy and thus to reliably compare reported results. Fourth, the comparative analyses that have been employed in analyzing the results of thymectomy have been flawed and misleading in many reported studies and analyses. And fifth, although a total thymectomy is considered indicated, there are controversies as to what constitutes complete removal of the thymus, whether it is necessary to remove microscopic foci of thymus, to what extent the various surgical resectional techniques accomplish the desired goal, and whether it makes a difference.

In this review based on a previous analysis by Jaretzki,19 the authors attempt to clarify these controversial issues. Evidence is also presented in support of the thesis that the more complete the thymic resection, the better the results. And most importantly, recommendations are submitted that well-designed, controlled prospective studies are mandatory if these controversies are to be resolved.

Rationale for Total Thymectomy

Total thymectomy has always been considered the goal of surgery in the treatment of MG. In 1941, Blalock and coworkers5 reported, “Complete removal of all thymus tissue offers the best chance of altering the course of the disease.” Most leaders in the field have subsequently reiterated this goal. Clinical observations have supported this thesis. Incomplete resections, both transcervical and transsternal, have been followed by persistent symptoms that were later relieved by the removal of residual thymus at reoperation. In addition, studies by Masaoka and Monden36 and Matell and associates,39 comparing aggressive with limited resections, support the premise that the more thymus is removed, or more precisely the less thymus left behind, the higher the remission rate.

Furthermore, Penn and colleagues51 have demonstrated that complete neonatal thymectomy in rabbits prevents experimental autoimmune MG whereas incomplete removal does not; and it has now been demonstrated, as indicated by Wekerle and Müller-Hermelink,65 that the thymus plays a central role in the autoimmune pathogenesis of MG.

Accordingly, support of the view that a total thymectomy is indicated has been virtually unanimous. Recently, however, in defense of extended transcervical and video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) thymectomy techniques, Mack31,32 and Suen and Cooper62 have questioned the necessity of removing all the perithymic fat, even though this fat is known to frequently contain microscopic foci as well as lobules of thymus.

Surgical Anatomy of the Thymus

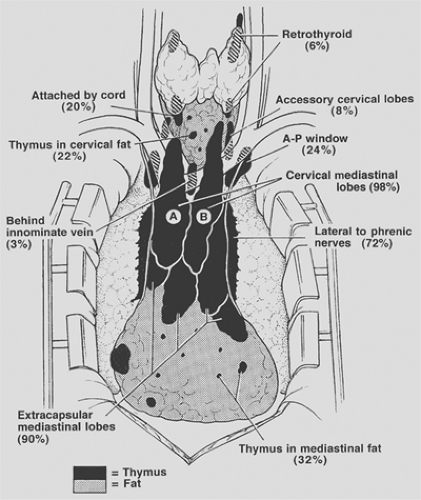

Surgical–anatomic studies by Jaretzki and Wolff20 on patients with nonthymomatous MG have demonstrated that the thymus is widely distributed in the neck and mediastinum, that the lobar anatomy is variable, that thymus may be unencapsulated and have the appearance of fat, and that small lobules and microscopic foci of thymic tissue may be invisibly distributed in the pretracheal and anterior mediastinal fat from the level of the thyroid to the diaphragm. The presence of thymus in these locations is further confirmed by the findings of thymomas in all these locations, and multiple authors have corroborated pathologically the finding of thymic tissue outside the confines of the anatomic lobes of thymus. The anatomic distribution of thymus and frequency of location is depicted in Figure 187-1.

In the neck, thymus was found outside the confines of the classic cervical–mediastinal lobes (see Fig. 187-1A,B) in 32% of the specimens. Retrothyroid thymus was found as high as the hyoid bone, accessory cervical thymic lobes were medial or lateral to the classic cervical–mediastinal lobes, and gross and microscopic thymus was found in the pretracheal fat. Thymus may also be present in the parathyroid glands or within the thyroid gland.

In the mediastinum, thymus was found outside the confines of the classic cervical–mediastinal lobes in 98% of the specimens. The thymic lobes were also usually adherent to the mediastinal pleura and pericardium so that attempts to separate the thymus from the pleura and sweep it off the pericardium by blunt dissection resulted in microscopic thymus being left on both surfaces. The thymus extending to and beyond the phrenic nerves consisted of thin, friable, unencapsulated sheets of thymofatty tissue, frequently with the gross appearance of fat. The microscopic thymus in the anterior mediastinal fat distal to the thymic lobes extended to the diaphragm, and lobules of thymus were occasionally found in the cardiophrenic fat.

The thymus in the aortopulmonary window region was not encapsulated or localized, usually had the gross appearance of fat, and extended from the level of the pulmonary artery to or above the aortic arch, deep behind the left innominate vein. Superiorly on the right, thymus, when present, was medial or lateral to the superior vena cava and behind the origin of the left innominate vein.

Additionally, in a subsequent autopsy study by Fukai and colleagues,15 microscopic foci of thymus were found in the subcarinal fat in 7.5% of the specimens.

Extent of Thymic Resections

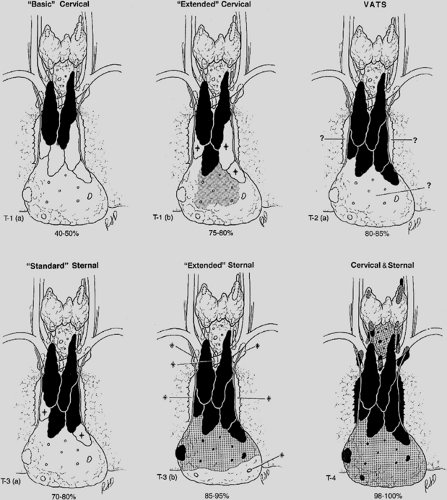

To assist in understanding and defining the extent of the various thymic resections, the Myasthenia Gravis Task Force, as reported by Jaretzki and colleagues,22,23 developed a thymectomy classification that we modified to include several additional thymectomy procedures now in use (Table 187-1). Estimates of the extent of thymic and perithymic fat removed are graphically presented in Figure 187-2. These estimates are based on personal experience; published operative descriptions, illustrations, and photographs of the resected specimens; and review of videos of the resections when available. In addition, pathologic analysis of thymectomy specimens (Table 187-2), further confirm the anatomic and clinical observations that the more extensive the removal of perithymic cervical and mediastinal fat, the more complete the removal of the thymic tissue lying outside the confines of the defined encapsulated thymic lobes. Details of the resections are recorded in the appendix of the Myasthenia Gravis

Task Force report22,23 and further discussed below. These observations indicate that all resections are almost certainly not equal in extent.

Task Force report22,23 and further discussed below. These observations indicate that all resections are almost certainly not equal in extent.

Table 187-1 Myasthenia Gravis Task Force Thymectomy Classification—Modified 2000 | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Basic Transcervical Thymectomy

The “basic” transcervical thymectomy (T-1a), as described by Kark and Kirschner,27 is limited to the removal of the intracapsular portion of the central lobes (see Fig. 187-1A,B). More recently, modifications include employing extracapsular dissection, and removal of some mediastinal fat separately. Although originally touted as a “total thymectomy” by Kark and Kirschner,27 it is unequivocally a limited resection, incomplete in both the neck and mediastinum.

The limited extent of these resections is confirmed by the findings of 2 to 60 g of residual thymus following many

reoperations after an initial transcervical resection, including the finding of a thymoma by Austin and coworkers.2

reoperations after an initial transcervical resection, including the finding of a thymoma by Austin and coworkers.2

Table 187-2 Extent of Thymic Tissue Recovered From Resected Perithymic Mediastinal Fat | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Extended Transcervical Thymectomy

The “extended” transcervical thymectomy (T-1b) was designed by Cooper and associates.10 Variations include the addition of a partial median sternotomy and the associated use of mediastinoscopy. The proponents of these techniques have claimed that about the same amount of tissue is removed as the aggressive transsternal procedures. However, as reported by Shrager58 and coworkers, cervical and mediastinal perithymic fat (which may contain thymus) may not be removed, and as warned by Cooper and associates,10 referring to its use in general, this resection appears to be usually less extensive than the original description.

Classic Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery Thymectomy

The “classic” VATS thymectomy (T-2a) has a number of proponents. No attempt is made to remove the accessory thymus in the neck. Variations include an “infrasternal mediastinoscopy” by Uchiyama and colleagues.63 In a surgical–anatomic study on eight cadavers by Ruckert and colleagues,54 incomplete resection was more frequent with the right-sided approach than the left. As warned by Mack and Scruggs,32 “thymectomy is an advanced VATS procedure that should only be undertaken by surgeons … well versed in simpler VATS operations and who have the enthusiasm and patience to pursue minimally invasive techniques.”

Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery Extended Thymectomy

The video-assisted thoracic surgery extended thymectomy (VATET T-2b) was described by Novellino46 and includes bilateral thoracoscopic approaches as well as a standard neck dissection. Although conceptually, both in the neck and the mediastinum, this procedure should be more thorough than a unilateral VATS procedure, an undated video does not confirm the reported extent in either the neck or the mediastinum.

Standard Transsternal Thymectomy

The “standard” transsternal thymectomy (T-3a) was used by the pioneer Blalock.5 Currently, the resections are more extensive than the original procedure. Variations include the addition of the videoscope, and a partial sternotomy.

The findings of residual thymus in the neck and mediastinum at reoperation following standard transsternal resections by Jaretzki,20 Miller,40 and Rosenberg and their colleagues53 confirms that this technique may produce an incomplete resection. Accordingly, most MG centers since the early 1980s consider it incomplete and have abandoned it.

Extended Transsternal Thymectomy

The “extended” transsternal thymectomy was first described by Masaoka and Monden.56 There have been multiple variations since. A complete median sternotomy is usually performed. Variations include a partial sternotomy, and a “video-assisted inframammary incision.”

Although the present authors believe that ideally the extent of these procedures should be standardized to remove all the mediastinal tissue that is removed in the combined transcervical–transsternal procedure, including resection of the mediastinal pleural sheets and sharp dissection of the pericardium, as illustrated in the video by Steinglass and colleagues,61 the extent of the resections varies. In addition, since the cervical extensions of the thymus are usually removed from below, these techniques may leave small amounts of thymus in the neck. Importantly, however, as expressed by Mulder,42 many believe that the risk to the recurrent laryngeal nerves in performing an extended neck dissection is not justified by the small potential gain.

Combined Transcervical–Transsternal Thymectomy

The combined transcervical–transsternal thymectomy (T4), as described by Jaretzki20 and by Bulkley7 and their colleagues, predictably removes en bloc all surgically available thymus from above the thyroid to the diaphragm, in the chest from phrenic to phrenic nerves (and beyond), and in the neck from recurrent to recurrent nerves. The en bloc technique, the sharp dissection on the pericardium, and the removal of the mediastinal pleural sheets en bloc with the specimen are integral to the procedure. Cooper and coworkers11 have described the “maximal” resection as the benchmark against which the other resectional procedures should be measured.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree