INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Indications

Patients for whom postoperative adjuvant therapy is indicated due to a locally advanced tumor or because a complete (R0) resection in the native esophageal bed is questionable.2

Patients for whom postoperative adjuvant therapy is indicated due to a locally advanced tumor or because a complete (R0) resection in the native esophageal bed is questionable.2

Delayed reconstruction in patients with esophageal exclusion and cervical esophagostomy.

Delayed reconstruction in patients with esophageal exclusion and cervical esophagostomy.

Previous posterior mediastinal surgery (for instance, repair of a thoracic esophageal fistula).

Previous posterior mediastinal surgery (for instance, repair of a thoracic esophageal fistula).

Relative Contraindications

Young patients or patients with a benign esophageal lesion, in whom a cardiac surgery may be required in the foreseeable future.

Young patients or patients with a benign esophageal lesion, in whom a cardiac surgery may be required in the foreseeable future.

Previous anterior mediastinal surgery.

Previous anterior mediastinal surgery.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Preoperative work-up begins with collection of a thorough medical and surgical history and a physical examination. Patients with previous anterior mediastinal surgery are not ideal for substernal reconstruction. If the patient has previously undergone partial gastric resection, or has a condition that might preclude application of the gastric tube as the replacement conduit, an alternate conduit (typically colon) must be prepared.

Systemic assessment of nutritional status and hepatic, renal, and cardiopulmonary function are essential for perioperative treatment. Radiologic investigations, including a barium swallow and a computed tomography (CT) scan, are performed to detect the location, length, and extent of the local lesion. To improve the staging, an endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), and a positron emission tomography (PET) scan may be complementary to determine the T, N, and M status. In some cases, we perform laparoscopic staging to further evaluate the patient for possible immediate surgical resection versus neoadjuvant treatment. Esophagogastroscopy must be performed to obtain a biopsy for histologic diagnosis and ensure suitability of the gastric conduit as an esophageal replacement.

SURGERY

SURGERY

Anatomy

The substernal route lies in the anterior mediastinal space between the sternum and the pericardia and the large vessels. Gastric, colonic, and jejunal interposition can all be achieved through the substernal route. Currently, there is a debate regarding whether reconstruction using the stomach substernally results in a longer distance for the conduit to travel. Limited cadaveric anatomic studies indicated that the prevertebral route was 2 to 3 cm shorter than the substernal route.3,4 In some instances, this has been used as an argument against the substernal pull-up procedure. However, we questioned whether the subject and reference selection in these studies was representative of that seen clinically in our practice. Therefore, we examined patients who underwent surgery at our institution and found that the substernal route was unexpectedly 2.8 cm shorter than the prevertebral route.5

Position and Incision

In this procedure, the patient should be placed in the supine position. The location of the incision depends on the purpose of the surgery. Usually, a midline laparotomy incision and an oblique cervical incision are necessary for a substernal pull-up procedure with an anastomosis at the neck. A laparoscopic approach is also considered appropriate for experienced and well-trained surgeons.

Operative Technique

Here we describe the main surgical techniques when a gastric tube is formed as the conduit to substitute for the esophagus.

The stomach is isolated and the gastric conduit is constructed as described in other chapters. Because a cervical anastomosis will be constructed, the conduit has to be completed in the abdomen (Fig. 25.1). Different surgeons have recommended differing conduit diameters, ranging from as small as 2.5 to 3 cm in diameter to as large as 6 to 8 cm.6–9 We prefer a gastric conduit approximately 4 to 6 cm in diameter for substernal pull-up because we believe an excessively narrow conduit might increase the incidence of cervical anastomotic leaks (Fig. 25.2). Usually, a 30- to 35-cm long conduit is long enough for substernal pull-up to reach the hypopharynx, though a longer tube can be fashioned, if needed.

The stomach is isolated and the gastric conduit is constructed as described in other chapters. Because a cervical anastomosis will be constructed, the conduit has to be completed in the abdomen (Fig. 25.1). Different surgeons have recommended differing conduit diameters, ranging from as small as 2.5 to 3 cm in diameter to as large as 6 to 8 cm.6–9 We prefer a gastric conduit approximately 4 to 6 cm in diameter for substernal pull-up because we believe an excessively narrow conduit might increase the incidence of cervical anastomotic leaks (Fig. 25.2). Usually, a 30- to 35-cm long conduit is long enough for substernal pull-up to reach the hypopharynx, though a longer tube can be fashioned, if needed.

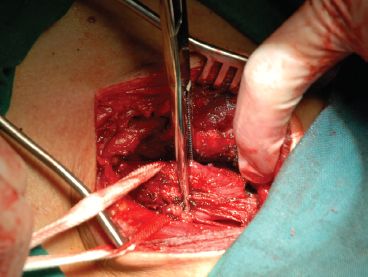

Figure 25.1 The gastric conduit can be created with a stapler as described in other chapters.

An optional Kocher maneuver may give extra mobility to the conduit during the gastric pull-up. In the authors’ practice, this procedure is not routinely performed, and usually the complete Kocher maneuver is not necessary.

An optional Kocher maneuver may give extra mobility to the conduit during the gastric pull-up. In the authors’ practice, this procedure is not routinely performed, and usually the complete Kocher maneuver is not necessary.

We routinely perform a jejunostomy for an enteral feeding tube. We prefer jejunostomy tube feeding over nasal tube feeding for the comfort of the patient. In addition, we believe nasal tube feeding might increase the risk of aspiration.

We routinely perform a jejunostomy for an enteral feeding tube. We prefer jejunostomy tube feeding over nasal tube feeding for the comfort of the patient. In addition, we believe nasal tube feeding might increase the risk of aspiration.

Figure 25.2 A gastric conduit 4 to 6 cm in diameter is recommended.

Figure 25.3 The cervical esophagus is identified and dissected, while the left recurrent laryngeal nerve should be distinguished and protected.

An oblique cervical incision is made anterior to the left sternocleidomastoid muscle. The space between the carotid sheath and the trachea is dissected, and the cervical esophagus is identified and dissociated from the carotid artery, internal jugular vein, and the left side of the thyroid gland. It is important to distinguish and protect the left recurrent laryngeal nerve, which lies in the tracheoesophageal groove (Fig. 25.3).

An oblique cervical incision is made anterior to the left sternocleidomastoid muscle. The space between the carotid sheath and the trachea is dissected, and the cervical esophagus is identified and dissociated from the carotid artery, internal jugular vein, and the left side of the thyroid gland. It is important to distinguish and protect the left recurrent laryngeal nerve, which lies in the tracheoesophageal groove (Fig. 25.3).

In our practice, instead of removing the left sternoclavicular joint,10 we incise part of the sternothyroid muscle inside the sternum, when needed, to expand the thoracic inlet and decrease the pressure caused by muscle contraction, thus alleviating compression on the microvascular network in the gastric wall.

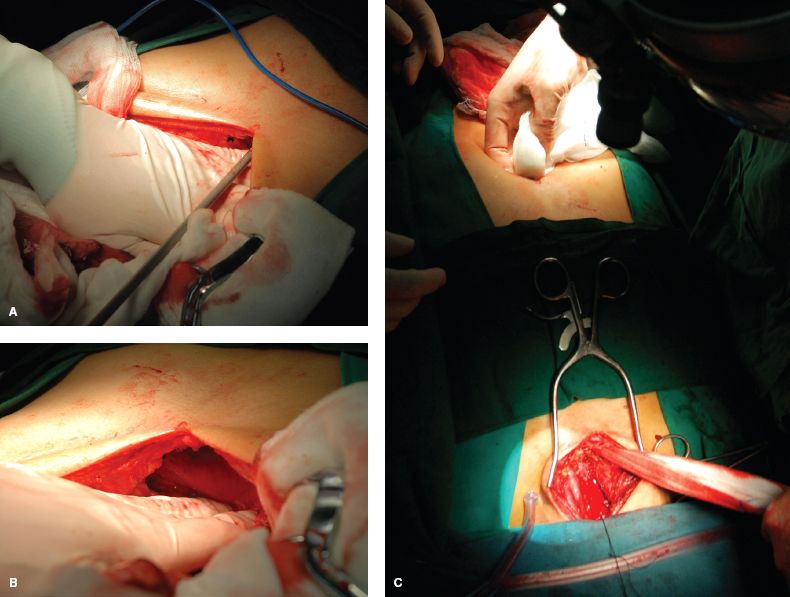

After that, a space within the retrosternal mediastinum was created and widened using a combination of blunt and sharp dissection under direct visualization, and the width of the tunnel is expanded as much as possible (Fig. 25.4A to C).

After that, a space within the retrosternal mediastinum was created and widened using a combination of blunt and sharp dissection under direct visualization, and the width of the tunnel is expanded as much as possible (Fig. 25.4A to C).

With combination of pushing and carefully pulling, the conduit can then be positioned substernally (Fig. 25.5A to C). It can also be placed in a plastic bag, such as a laparoscopic camera bag, which is tied and guided cephalad by pulling on an umbilical tape.

With combination of pushing and carefully pulling, the conduit can then be positioned substernally (Fig. 25.5A to C). It can also be placed in a plastic bag, such as a laparoscopic camera bag, which is tied and guided cephalad by pulling on an umbilical tape.

Fix the proximate portion of the gastric tube with the surrounding tissues at the neck and the distal part with peritoneum under the diaphragm (Fig. 25.6). This procedure is of great importance to avoiding twisting of the gastric conduit and postoperative hernia.

Fix the proximate portion of the gastric tube with the surrounding tissues at the neck and the distal part with peritoneum under the diaphragm (Fig. 25.6). This procedure is of great importance to avoiding twisting of the gastric conduit and postoperative hernia.

Anastomosis of the cervical esophagus may be performed with an end-to-end anastomosis using a hand-sewn, double-layer technique. Cervical drainage is then placed. Stapled anastomotic techniques have been described as well.

Anastomosis of the cervical esophagus may be performed with an end-to-end anastomosis using a hand-sewn, double-layer technique. Cervical drainage is then placed. Stapled anastomotic techniques have been described as well.

The laparotomy incision and the cervical incision are closed, and some patients may then be positioned in the left lateral decubitus position for a right thoracotomy, if indicated.

The laparotomy incision and the cervical incision are closed, and some patients may then be positioned in the left lateral decubitus position for a right thoracotomy, if indicated.

The esophagus is isolated from diaphragm to the thoracic inlet, and all lymph nodes are dissected. Note: This step is optional and not performed in most palliative cases.

The esophagus is isolated from diaphragm to the thoracic inlet, and all lymph nodes are dissected. Note: This step is optional and not performed in most palliative cases.

POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Most patients are extubated immediately in the operation room and transferred to ICU. Postoperative management includes adequate pain control, intravenous fluid support, prophylactic antibiotic, anticoagulants, antacids, and enteral nutrition. Enteral nutrition through jejunostomy tube feeds begins 24 hours postoperatively. If no anastomotic leak is identified and satisfactory gastric emptying is demonstrated, the nasogastric tube can be removed and oral food or fluids can be taken, generally beginning on postoperative day 5–7, based on the patient’s status. The patient is then allowed to slowly progress with oral intake. Later, the cervical drainage tube can be removed if the volume is limited and there is no sign of leak, generally around postoperative day 7. When the patients are discharged, usually on day 7, they should be able to manage several small meals of a soft diet every day. The jejunostomy tube is kept in place and used for additional nutritional support till the patient’s first postoperative follow-up.

Figure 25.4 A to c: The substernal route is created under direct visualization by a combination of sharp and blunt dissection and should be as wide as possible.