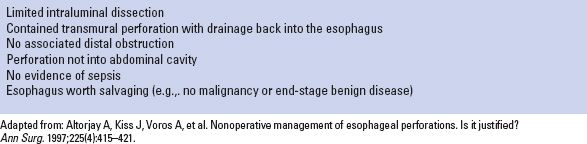

Figure 36.1 Chest radiograph demonstrating extravasation of oral contrast into the mediastinum following a cervical esophageal perforation sustained during transesophageal echocardiography. The patient had a history of chronic bronchiectasis involving the left lung. The perforation was successfully managed by left cervicotomy and laparotomy with placement of drains into the neck as well as into the mediastinum via the neck and the hiatus.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

The initial diagnostic examination to evaluate a patient with a suspected esophageal perforation is a chest radiograph. It is a quick and inexpensive test that may reveal a pleural effusion (frequently unilateral), pneumothorax, pneumoperitoneum, subcutaneous or mediastinal emphysema, or mediastinal widening. A normal chest radiograph, however, does not exclude the diagnosis of an esophageal perforation, especially when contained or in the early time period after the suspected insult.

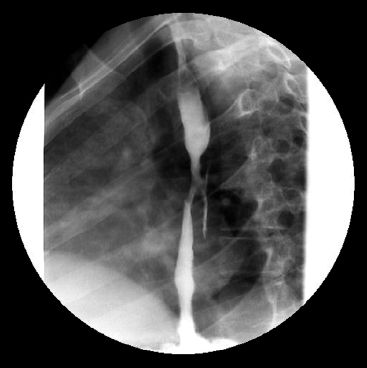

The most widely utilized radiologic test for esophageal perforation has been a contrast esophagogram (Fig. 36.2). Traditional teaching has been to commence the study with a water-soluble contrast agent, such as Gastrografin (Bracco Diagnostics Inc., Princeton, NJ), out of concern for exacerbating mediastinal, pleural, or abdominal contamination should barium be leaked. This examination requires an alert and cooperative patient who is able to swallow without aspirating, because Gastrografin has the potential to induce a severe chemical pneumonitis. Judgment must be exercised in considering this study for the elderly patient or others at high risk for aspiration, as any resultant pulmonary injury can be a significant additional insult. The study typically provides a reasonable assessment of esophageal anatomy, the location and extent of the perforation (contained vs. free pleural or peritoneal rupture), and the presence of coexisting conditions such as an esophageal stricture, malignancy, diverticulum, or motility disorder. A negative study with Gastrografin should be followed by the use of thin barium to increase the sensitivity of the examination. Films also should be taken with the patient in both the left lateral and right lateral decubitus positions. A negative esophagogram, however, does not exclude the diagnosis, as the false-negative rate is 10% to 38%.4,5

Figure 36.2 Contrast esophagogram demonstrating contained leakage of oral contrast due to perforation of a midesophageal stricture sustained during attempted esophageal dilation.

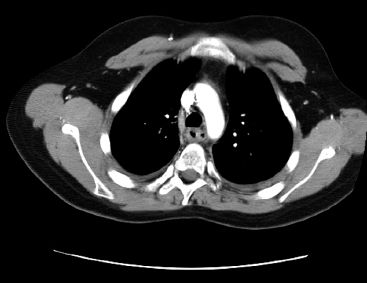

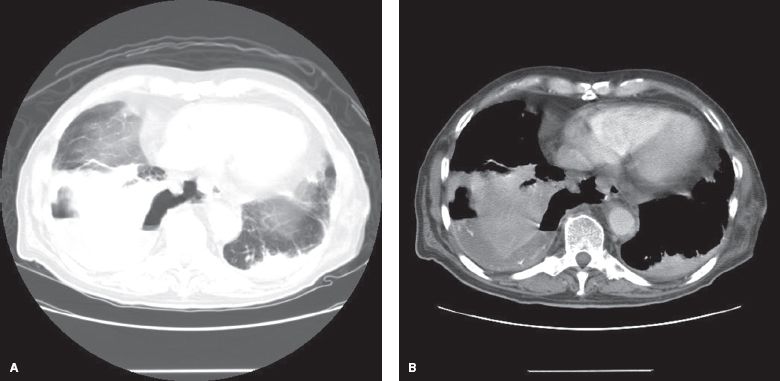

More recently, computed tomography (CT) has proven an extremely useful diagnostic modality for assessing the various manifestations of esophageal rupture (Figs. 36.3 and 36.4). The CT findings suggestive of perforation include pneumomediastinum, pneumoperitoneum, subcutaneous emphysema, mediastinal fluid collection or inflammatory changes, pleural effusion, or abdominal abscess. The definitive finding of frank leakage of oral contrast is not always seen and should not be relied upon to prove or disprove the diagnosis. Importantly, CT provides critical information regarding the extent and location of any extraesophageal fluid collections that may require operative intervention or percutaneous drainage.5,6

Figure 36.3 Computed tomography of the chest from the same patient shown in Figure 36.2, demonstrating the thickened midesophagus at the site of stricturing and pneumomediastinum resulting from the contained perforation.

Figure 36.4 A, B: Computed tomography of the chest demonstrating a large right hydropneumothorax, mediastinal air, right lower lobe lung consolidation, and small amount of extravasation of oral contrast into the right pleural space, diagnostic of esophageal perforation.

Finally, upper endoscopy serves a critical role in the assessment of the full spectrum of esophageal pathology including perforations. Not only can endoscopy determine the location and size of a mucosal injury, but it also allows identification of concomitant mucosal ischemia, inflammation or ulceration, as well as more chronic or subacute pathology such as a stricture, diverticulum, or malignancy. While concern may exist about the safety of flexible endoscopy, with its need for insufflation, in the setting of acute perforation, the examination typically can be completed in experienced hands without impact on the extent of injury and provides invaluable information. Insufflation should be kept at the minimum level necessary for adequate visualization of the entire mucosa. Consideration should be given to placement of a chest tube prior to the procedure if concern exists about the potential to induce or exacerbate a pneumothorax. Some perforations are subtle and may not demonstrate an obvious tear, but rather only an ecchymotic and slightly disrupted mucosa that flutters with insufflation. As a therapeutic maneuver, endoscopy can be utilized for irrigation and suctioning of contained extraluminal fluid collections, and may even assist with guidance of chest tube placement by advancement of the flexible endoscope through a transmural perforation into the pleural space.

Unfortunately, no diagnostic examination is perfect in the evaluation of esophageal perforation. Esophagography is limited by its false-negative rate and the risk of aspiration, as well as the relative inability to assess mucosal detail. CT is poor at localizing perforations and detecting pre-existent esophageal pathology. Endoscopy is invasive and does not usually allow determination of the extent of extraesophageal contamination. Considerable judgment, therefore, is required in deciding the order and number of diagnostic studies based upon the clinical suspicion, information desired, patient tolerance, and possible therapeutic considerations. A point worthy of emphasis is that the location and extent of perforation must be determined prior to any surgical intervention, in that the planning of incisions and the type of procedure performed will depend critically on the diagnostic findings.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

Principles of Initial Management

The major sequelae of esophageal perforation are sepsis and death resulting from leakage of gastrointestinal contents. Accordingly, the mainstays of treatment are: (1) Eliminating the source of sepsis by repairing or otherwise controlling the leak, and (2) drainage of extraluminal fluid collections. Any treatment strategy, whether nonoperative, endoscopic or operative, must address these two fundamental principles.

Initial therapy should include avoidance of food by mouth, administration of intravenous fluids, and initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Leaked enteric contents incite a chemical burn in the mediastinum, pleural space, or peritoneal cavity and may lead to sequestration of large amounts of fluid, further exacerbating hypotension from developing sepsis. Antibiotics should be directed toward a polymicrobial infection including gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic bacteria. In addition, antifungal agents should be considered in those individuals with a history of long-standing proton pump inhibitor use, due to the increased risk of fungal colonization in the stomach.7 Chest tube thoracostomy should be considered early to drain large pleural effusions while preparations are made for definitive intervention.

Determining the Treatment Plan

The overall treatment plan must be individualized, considering the spectrum of nonoperative, endoscopic, and operative alternatives. The criteria for nonoperative management have been elucidated, though considerable judgment may be required in deciding when to utilize or abandon such an approach. Available endoscopic therapies include fully covered stents or mucosal clips. Surgical options include primary repair of the perforation, esophagectomy, wide drainage, and esophageal exclusion or diversion. If endoscopic therapy is pursued, one must consider drainage and/or debridement of any periesophageal collections which might be accomplished percutaneously, thoracoscopically or with open surgery. As multiple treatment strategies exist, the decision regarding how best to intervene may not be an easy one. Important questions to guide decision making include the following.

What is the etiology of the perforation?

What is the etiology of the perforation?

Where is the perforation located (cervical, thoracic, or abdominal esophagus)?

Where is the perforation located (cervical, thoracic, or abdominal esophagus)?

Is it a contained perforation or free perforation into the pleural or peritoneal space?

Is it a contained perforation or free perforation into the pleural or peritoneal space?

How extensive is the extraluminal soilage?

How extensive is the extraluminal soilage?

What is the time interval since the perforation?

What is the time interval since the perforation?

What is the clinical condition of the patient and what are their comorbidities?

What is the clinical condition of the patient and what are their comorbidities?

Is there pre-existing esophageal pathology?

Is there pre-existing esophageal pathology?

Is the esophagus worth salvaging?

Is the esophagus worth salvaging?

Does the patient meet criteria for nonoperative management?

Does the patient meet criteria for nonoperative management?

Nonoperative Management

For decades, surgery was the preferred treatment modality for esophageal perforation, but was associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality. In carefully selected patients, a nonoperative approach has proven successful and has avoided the potential complications of esophageal surgery in the emergent setting. The criteria for nonoperative management were initially described by Cameron et al. and modified by Altorjay (Table 36.1).14,15 The initial experience was in management of patients sustaining a spontaneous perforation, though the data have been extrapolated to other causes of perforation as well. In general, patients selected for nonoperative management have limited perforations with minimal extraluminal contamination that is contained by adjacent tissues (Fig. 36.3). Other important considerations include absence of sepsis, no associated distal obstruction, and an esophagus worth salvage (i.e., no malignancy or end stage benign disease). Patients who meet these criteria can be treated with intravenous antibiotics and nothing by mouth. The duration of such therapy is predicated by the patient’s overall condition. Repeat endoscopy or radiographic imaging is useful in determining the response to treatment and when to resume a diet. The development of sepsis mandates repeat investigation and strong consideration of more invasive therapeutic measures.

TABLE 36.1 Suggested Criteria for Nonoperative Management of an Esophageal Perforation