Esophageal Diverticula

Stephen D. Cassivi

Francis C. Nichols

Claude Deschamps

Esophageal diverticula are acquired conditions of the esophagus occurring almost exclusively in adults. An esophageal diverticulum is an epithelium-lined blind pouch arising from the esophagus. There are two categories: pulsion diverticula and traction diverticula. Pulsion result from transmural pressure gradients that develop from within the esophagus. This results in herniation of the mucosa through a weak point in the muscle layer (pseudodiverticulum). Two types of pulsion diverticula are recognized: pharyngoesophageal (Zenker’s) and epiphrenic. The second category, traction diverticulum, results from inflammation and fibrosis in adjacent lymph nodes and is composed of all layers of the esophageal wall (true diverticulum). There is also a very rare entity called diffuse intramural esophageal diverticulosis.

Pharyngoesophageal (Zenker’s) Diverticulum

The pharyngoesophageal diverticulum, the most common diverticulum of the esophagus, is situated posteriorly just proximal to the cricopharyngeus muscle. It is most prevalent in the fifth to eighth decades of life. Although first described in 1769 by the English surgeon Ludlow, it was as a consequence of the classic review written by the German pathologists Zenker and von Ziemssen in 1874 that the eponym Zenker’s diverticulum arose.44,79

Pathophysiology

The cause of pharyngoesophageal diverticulum is not completely understood. Because it is usually seen in patients >50 years of age and rarely in those <30 years of age, it is considered an acquired condition. Negus52 concluded, however, that the constant site of origin just above the cricopharyngeus muscle suggests the possibility of an anatomic weak point in the muscular layers as well as some distal obstructive role of the cricopharyngeus muscle. While considerable speculation about the nature of this obstruction has developed since the report of Zenker and von Ziemssen, most of the disorders described have been based more on theory than on fact. Manometric studies conducted by Ellis23 at the Mayo Clinic did not confirm the presence of either achalasia or hypertension of the cricopharyngeus in patients with this diverticulum. Nevertheless, those studies did define an abnormal temporal relationship between pharyngeal contraction and sphincteric relaxation and contraction with swallowing. In patients with diverticula, upper esophageal sphincteric contraction occurred before completion of pharyngeal contraction. Thus, premature contraction of the upper sphincter was implicated as characteristic of pharyngoesophageal diverticulum. While these studies provided a definite pattern of the events occurring in patients with diverticula, they failed to define the cause of the diverticulum. The fact that premature sphincteric contraction was noted both in small, early diverticula as well as in large, established ones implicates cricopharyngeal incoordination as a potential cause.

An evaluation by Lerut40 of the characteristics of the muscles making up the upper esophageal sphincter area suggests that myogenic degeneration and neurogenic disease are not limited to just the cricopharyngeus muscle but affect the striated muscles as well. Therefore incoordination of the cricopharyngeus muscle could be considered only one aspect of a more complex functional problem rather than a disease on its own, and a pharyngoesophageal diverticulum could be just one expression of this process. Venturi and associates74 also showed that there is a higher collagen-to-elastin ratio in the cricopharyngeus muscle as well as the upper esophageal muscularis propria in patients with a Zenker’s diverticulum as compared with controls. This suggests a primary difference in the biochemical composition of the muscles of the upper esophageal sphincter area.

Cook and coauthors16 studied patients with Zenker’s diverticula and controls using simultaneous videoradiography and manometry. They were able to document significantly reduced sphincter opening and greater intrabolus pressure in patients with Zenker’s diverticulum. They concluded that the primary abnormality in patients with Zenker’s diverticulum is one of incomplete upper esophageal sphincter opening rather than abnormal coordination between pharyngeal contraction and upper esophageal sphincter relaxation or opening. Thus, the act of swallowing in the presence of cricopharyngeal dysfunction, combined with the usual pressure phenomena during deglutition, is believed to generate sufficient transmural pressure to allow mucosal herniation through an anatomically weak point in the posterior pharynx above the cricopharyngeus muscle. Owing to the recurrent nature of the pressures involved and the constant distention of the sac with ingested material, the established diverticulum enlarges progressively and descends dependently. The neck of the diverticulum hangs over the cricopharyngeus, and the sac becomes interposed between the esophagus and the vertebrae. Indeed, an advanced diverticulum may come to

lie in the same vertical axis as the pharynx, permitting selective filling of the sac, which may compress and cause the adjacent esophagus to angle anteriorly. These anatomic changes further obstruct swallowing. Moreover, because the mouth of the diverticulum is above the cricopharyngeus, spontaneous emptying of the diverticulum is unimpeded and is often associated with laryngotracheal aspiration as well as regurgitation into the mouth.

lie in the same vertical axis as the pharynx, permitting selective filling of the sac, which may compress and cause the adjacent esophagus to angle anteriorly. These anatomic changes further obstruct swallowing. Moreover, because the mouth of the diverticulum is above the cricopharyngeus, spontaneous emptying of the diverticulum is unimpeded and is often associated with laryngotracheal aspiration as well as regurgitation into the mouth.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Although a Zenker’s diverticulum may be asymptomatic, most patients develop symptoms early in the course of the disease. Once the condition is established, it progresses both in size and in the frequency and severity of symptoms and complications. Characteristically, the symptoms consist of high cervical esophageal dysphagia, halitosis, noisy deglutition, and spontaneous regurgitation with or without coughing or choking episodes. The regurgitated food is characteristically fresh and undigested; it is not bitter, sour, or contaminated by gastroduodenal secretions. The chief complications of a pharyngoesophageal diverticulum are nutritional and respiratory. If the condition is neglected, weight loss, hoarseness, asthma, respiratory insufficiency, and pulmonary sepsis leading to abscess are all potential complications. A palpable cervical mass is rarely noted. Carcinoma arising in a pharyngoesophageal diverticulum is extremely uncommon and is of the squamous cell type.10,63,78 Iatrogenic diverticular perforation may occur with esophageal intubation, instrumentation, or the accidental ingestion of a foreign body.

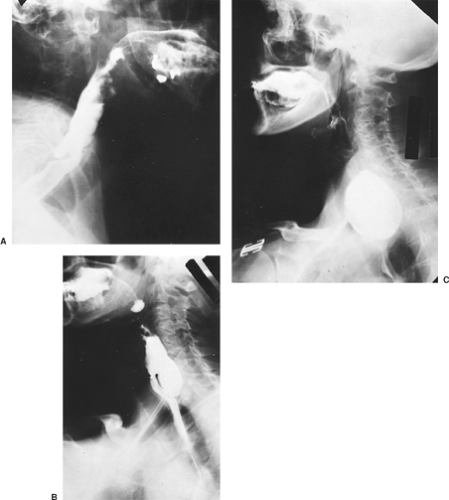

The diagnosis is confirmed by a barium swallow, which demonstrates the sac (Fig. 156-1). Manometry and endoscopy are of little clinical value in this setting. However, if an endoscopy is indicated for other reasons, the endoscopist should be warned of the possibility of a pharyngoesophageal diverticulum because of the risk of perforation with the endoscope.

Treatment

The treatment of a pharyngoesophageal diverticulum is surgical. There is no medical therapy for this condition, and all patients with such diverticula should be considered candidates for surgical treatment irrespective of the size of the diverticulum.11 Nutritional or chronic respiratory complications are not contraindications to the surgery. To the contrary, as emphasized by Payne,57 operative repair in such patients should be performed promptly, since recurrent episodes of aspiration are poorly tolerated in this elderly population. Advanced age is therefore not a contraindication to surgical treatment. A review from the Mayo Clinic of patients ≥75 years of age who underwent surgical treatment of a Zenker’s diverticulum demonstrated improvement in 94% and no operative deaths.17 In a similar modern series, 99% of patients treated with cricopharyngeal myotomy had excellent results.38 Treatment is best performed on an elective basis while the pouch is of small or moderate size and before complications have occurred. When nutritional or respiratory complications are present or when neoplasia is suspected, surgical intervention is more urgent. Diverticular perforation is a surgical emergency.

Surgical treatment has evolved from the two-stage diverticulectomy of the early 1900s, which was popularized by Coldmarm and C. H. Mayo and reported by Lahey and Warren.39 The one-stage diverticulectomy was shown to be highly successful in numerous large series.14,30,56 Because of our experience at the Mayo Clinic with cricopharyngeal myotomy and similar reports by Orringer and Duranceau, we recommend this procedure alone for small diverticula.17,21,23,26,54,65 We reserve diverticulectomy combined with myotomy for larger sacs. Myotomy combined with diverticulopexy has been described by multiple groups, though initially by Belsey.6,21,41,42 A recent comparison of these differing techniques found that diverticulectomy without myotomy predisposed the patient to developing postoperative fistulas and late diverticular recurrences, thus emphasizing the importance of myotomy in the treatment of this disorder.27

Other approaches have also been used successfully. Dohlman and Mattsson first described peroral endoscopic diathermic division of the septum or common wall between the diverticulum and the esophagus.19 This technique was popularized in the United States by Holinger and Schild32 and by van Overbeek in the Netherlands.32,70,71 Additionally, van Overbeek72 has described the use of a carbon dioxide laser to divide the common wall. Collard15 and Peracchia58 have used an endoluminal stapler to effect an endoscopic cricopharyngeal myotomy. Collard’s extended experience, over 16 years, was recently published.27 It showed that open techniques provide improved symptomatic relief over endoscopic techniques. This was especially true with smaller diverticula. A recent North American series demonstrated the feasibility of endoscopic stapling for the treatment of Zenker’s diverticula. However, when compared with a contemporaneous but nonrandomized cohort of patients undergoing open cricopharyngeal myotomy, the endoscopic stapling technique did not show any difference in postoperative dysphagia scores, length of hospitalization, and time to oral intake.50

Most patients undergoing surgical treatment require little or no preoperative preparation. Rarely are nutritional deficiencies severe enough to require preoperative parenteral hyperalimentation or gastrostomy. Prompt repair of the diverticulum provides the best means of correcting most deficiencies. Suppurative lung diseases also often require definitive resolution of the diverticular problem before they can be managed effectively. Occasionally, esophageal bougienage improves obstructive symptoms and temporarily palliates nutritional and respiratory complications, but the patient is usually best served by prompt surgical treatment of the diverticulum.

Surgical Technique

Open Cricopharyngeal Myotomy with or Without Diverticulectomy

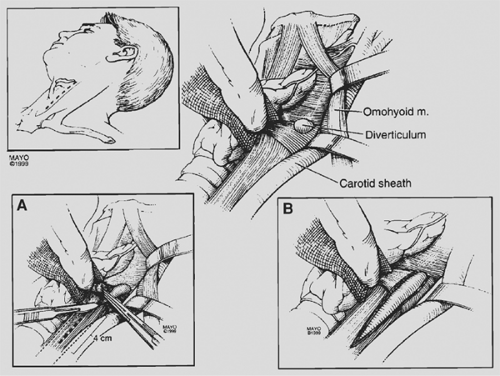

Two techniques are currently used at the Mayo Clinic: cricopharyngeal myotomy alone for small sacs (Fig. 156-2) and one-stage pharyngoesophageal diverticulectomy with cricopharyngeal myotomy for the larger ones (Fig. 156-3). Regional cervical blocks or general anesthesia can be used satisfactorily; however, currently almost all patients receive general anesthesia with a cuffed endotracheal tube. This technique controls ventilation as well as the airway and prevents intraoperative aspiration. Various incisions can be used, depending on whether myotomy with or without diverticulectomy is planned. Right-handed surgeons find the left cervical approach easiest for exposing most diverticula. Usually, an oblique incision paralleling the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and extending from the level of the hyoid bone to a point 1 cm above the clavicle is utilized.

By retracting the sternocleidomastoid muscle and carotid sheath laterally and the thyroid gland and larynx medially, the retropharyngeal space and diverticulum are exposed. The diverticulum can promptly be recognized as arising from the posterior wall of the pharynx just above the level where the omohyoid muscle crosses the incision (Fig. 156-3).

By retracting the sternocleidomastoid muscle and carotid sheath laterally and the thyroid gland and larynx medially, the retropharyngeal space and diverticulum are exposed. The diverticulum can promptly be recognized as arising from the posterior wall of the pharynx just above the level where the omohyoid muscle crosses the incision (Fig. 156-3).

Figure 156-1. Various sizes of pharyngoesophageal diverticula (lateral radiographic views). A: Small. B: Moderate. C: Large. |

Once the diverticulum is identified, it is mobilized and elevated with a clamp. At this point, a 36-Fr Maloney bougie may be introduced into the esophagus to facilitate the dissection. The area of the neck of the diverticulum is freed from surrounding fibrofatty tissue. Dissection of the neck of the diverticulum must be performed carefully so as not to injure the mucosa. The surgeon must thoroughly dissect out the diverticulum, identifying the margins of the pharyngeal muscular defect through which the mucosal sac protrudes. The myotomy is performed with the dilator in place. It is initiated at the neck of the diverticulum and extended inferiorly for approximately 4 cm. Simultaneously, a Kittner dissector is used to retract the divided muscle layer laterally. The myotomy is placed roughly at 135 degrees laterally from the anterior aspect of the esophagus. Most sacs <2 cm simply disappear after the myotomy. For diverticula between 2 and 4 cm, the diverticulum may be transected by the cut-and-sew technique and the mucosal defect closed with interrupted 4-0 or 5-0 vascular silk. Larger diverticula should be removed using

a TA stapling device.31 This improves the speed and accuracy of closure. To avoid stricture, the bougie is left in place while the stapler device is applied and fired. The bougie is removed, the mucosal closure is left uncovered, and a small suction drain (Jackson–Pratt) is placed in the retropharyngeal space. After the operation, the patient is managed routinely. A radiographic examination of the esophagus using contrast is done the next day; if this is satisfactory, a soft diet is started. The drain is then removed and the patient may be discharged on the second postoperative day. Two to three weeks later, a normal diet is resumed as tolerated.

a TA stapling device.31 This improves the speed and accuracy of closure. To avoid stricture, the bougie is left in place while the stapler device is applied and fired. The bougie is removed, the mucosal closure is left uncovered, and a small suction drain (Jackson–Pratt) is placed in the retropharyngeal space. After the operation, the patient is managed routinely. A radiographic examination of the esophagus using contrast is done the next day; if this is satisfactory, a soft diet is started. The drain is then removed and the patient may be discharged on the second postoperative day. Two to three weeks later, a normal diet is resumed as tolerated.

Endoscopic Transoral Stapled Diverticulotomy

Patients considered for this technique usually are those with a diverticulum of ≥3 cm in size in order to allow for introduction of the endoscopic stapling device and effectively transect the cricopharyngeus muscle. Relative contraindications to this procedure include patients with a significant overbite or limited ability to open their mouths.

Under general anesthesia, the posterior oropharynx and upper esophagus is visualized using a Weerda laryngoscope. The laryngoscope is positioned with the anterior jaw in the esophagus and the posterior jaw in diverticulum. The common septum, located at the level of the neck of the diverticulum and formed by the cricopharyngeus muscle, is visualized by opening the jaws of the laryngoscope. An endoscopic suturing device is then used to place a suture across the septum, allowing it to be retracted cephalad.

A special endoscopic stapling device (Endo-GIA) is used.50 It is modified by removing the tapered tip of the stapling anvil, thus allowing stapling and cutting to be performed to the very tip of the device and therefore to the base of the diverticulum. The modified anvil is positioned in the diverticulum, whereas the side of the stapling cartridge is positioned within the esophageal lumen. One or more applications of the stapling device may be required to allow for complete division of the common septum up to the base of the diverticulum. By dividing the entire common septum, the required cricopharyngeal myotomy is performed. Similar postoperative care is employed as in the open technique, although no drain is placed in the endoscopic technique. In some centers, this procedure is performed on an outpatient basis.62

Results

The Mayo Clinic experience with the open cricopharyngeal myotomy technique in patients ≥75 years of age demonstrated safety and excellent symptom relief.17 The median age was 79 years, with a range of 75 to 91 years. Preoperative symptoms included dysphagia in 69 patients (92%), regurgitation in 61 (1%), pneumonia in 9 (12%), halitosis in 3 (4%), and weight loss in 1 (1%). Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms were noted in 27 patients (36%). The diagnosis was made by barium swallow in 63 patients, by esophagoscopy in 5, and a combination of both in 7. There was no in-hospital mortality. Complications occurred in eight patients (11%) and included esophagocutaneous fistula in four, pneumonia and urinary tract infection in one, and wound infection, myocardial infarction, and persistent diverticulum in one patient each. Follow-up was available in 72 patients (96%) and ranged from 8 days to 17 years, with a median of 3.3 years. At follow-up, 64 patients (88%) were asymptomatic and 4 (6%) were improved with minimal symptoms. The remaining four patients (6%) had varying degrees of dysphagia, and all were treated with periodic esophageal dilatations. Lerut41 reported similar results: no postoperative mortality, minimal morbidity, and very good to excellent results in 96% of patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree