Esophageal Conduits and Palliative Procedures

Jenifer L. Marks

Ara A. Vaporciyan

Esophageal cancer is on the rise throughout the world and esophageal adenocarcinoma is now the most common type of esophageal malignancy requiring surgical resection in the United States. Esophageal resection for benign and malignant cases mandates conduit creation to reestablish gastrointestinal continuity. There are a number of options for conduit creation, including the stomach, colon, jejunum, and a skin tube. Selection depends on a number of patient factors as well as a surgeon’s personal experience with any of the potential conduits. There are advantages and disadvantages for each conduit, and none has proven superiority in all settings. The stomach is the most widely used conduit and therefore has the most data on outcomes. The colon and jejunum are used less often, but are the first choice in some clinical settings such as when the stomach is not available. Skin tube reconstruction has also been described as an esophageal replacement, although utilized uncommonly today. Today’s thoracic surgeon must be familiar with all the conduit choices and understand the technique and implications of using each method for esophageal replacement.

STOMACH

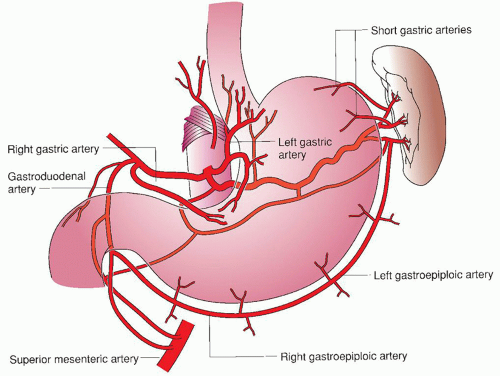

The stomach remains the most commonly used conduit for esophageal reconstruction. It is a large, durable organ with abundant native blood supply and it can be partially or completely tubularized and advanced into the chest or neck for anastomosis to the proximal esophagus. The most important aspect of preparing the stomach as an esophageal conduit is protecting the blood supply for the conduit, the right gastric and right gastroepiploic artery (Fig. 21.1). The remainder of the blood supply to the native stomach is sacrificed during mobilization of the stomach. This includes the short gastric vessels, the pancreaticogastrics, the left gastric artery, and the left gastroepiploic artery. The stomach when used as a conduit is able to survive on the blood supplied by the right gastroepiploic artery because of the stomach’s rich submucosal vascular networks. Radiation can damage these networks and one must always take this into account when operating on patients who have received prior radiation. Alternative conduits should be considered if the stomach does not appear viable after mobilization.

Several aspects of protecting the right gastroepiploic and its vessel of origin, the gastroduodenal artery, deserve mention. When mobilizing the greater curvature of the stomach, care must be taken to palpate the right gastroepiploic artery and stay a safe distance away from it when dividing the gastrocolic omentum with any energy source. Also, the stomach should not be grasped by the greater curvature itself but by the body of the stomach, using gauze or the nasogastric tube to maintain tension. When dissecting the distal greater curvature at the gastrocolic ligament, one must be aware of the gastroduodenal and gastroepiploic artery at all times as this region frequently has redundant folds of omentum making it difficult to identify the artery or the wall of the colon. Careful separation of these folds may be necessary to ensure preservation of the vessel and avoid injury to the colon wall.

The right gastroepiploic artery normally terminates approximately two-thirds of the way along the greater curvature. It is rare for there to be actual continuity in this region of the stomach with the left gastroepiploic or the short gastric vessels but infrequently a collateral arcade may be found within the gastrocolic ligament. This arcade supplies the area distal to the termination of the right gastroepiploic artery and, when preserved, can enhance the blood supply to the distal portion of a conduit. Any major injury or accidental ligation of the gastroduodenal or gastroepiploic artery requires the use of an alternative conduit for esophageal replacement.

The decision to tubularize the gastric conduit is surgeon dependent. Some surgeons prefer not to perform any tubularization, advancing the stomach essentially intact into the chest. While this is an acceptable approach, most surgeons feel that such a conduit leaves the patient more prone to reflux and difficulty with gastric emptying. Therefore, most surgeons advocate some type of tubularization of the stomach.

When performing an intrathoracic anastomosis, the tubularization of the conduit can be done in a number of ways. Some prefer to completely tubularize the stomach while in the abdomen after transection of the distal margin of the specimen. A 4-cm wide conduit is prepared by sequential firings of the GIA stapler with either 4.8 or 3.5 mm loads, depending on the thickness of the organ. The staple line begins at the incisura and ends at the cardia with the proximal extent based on the length of conduit needed and the location of the tumor. The stomach is uncurled and straightened with each successive firing allowing it to lengthen. Oversewing of this staple line with interrupted Lembert stitches for hemostasis as well as to reinforce the staple line may be added. Tubularizing the entire remaining stomach in such a manner provides the greatest possible length allowing the conduit to reach easily into the neck for a cervical anastomosis. For an intrathoracic anastomosis, the proximal end of the now tubularized stomach must be attached temporarily to the distal end of the specimen so that it can be delivered into the chest during the thoracotomy.

An alternate method, when creating a conduit for a thoracic anastomosis, still begins in the abdomen. One or two firings of the stapler are begun at the incisura extending toward to cardia, to begin

the tubularization of the conduit. The stomach is again uncurled as the staplers are applied. The specimen and the conduit remain attached. After the abdomen is closed and the chest is opened, the specimen and conduit are brought through the hiatus. The anastomosis is completed at an appropriate location on the greater curvature of the conduit. The gastric staple line is then completed allowing the specimen to be removed.

the tubularization of the conduit. The stomach is again uncurled as the staplers are applied. The specimen and the conduit remain attached. After the abdomen is closed and the chest is opened, the specimen and conduit are brought through the hiatus. The anastomosis is completed at an appropriate location on the greater curvature of the conduit. The gastric staple line is then completed allowing the specimen to be removed.

Fig. 21.1. Blood supply of stomach. (From Fiser SM. The ABSITE Review. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.) |

Using the stomach for esophageal replacement requires only one anastomosis. As such, it is less technically demanding than any other of the conduit choices. Disadvantages to using the stomach as a conduit include dumping syndrome, early satiety, chronic reflux of gastric contents into the remaining esophageal segment, and the risk of aspiration. Dumping syndrome and early satiety tend to improve with time and lifestyle/dietary modifications. Reflux, regurgitation, and aspiration persist for the remainder of the patient’s life and methods to prevent these sequelae must also be maintained.

Necrosis of the gastric conduit is a rare but very serious and sometimes fatal complication. The most proximal aspect of the conduit is most at risk for ischemia. Early postoperative acidosis or other signs of clinical deterioration should prompt esophagoscopy to determine the viability of the conduit. Focal areas of mucosal ischemia can be watched closely as they may progress. An anastomotic leak may also be an early sign of partial conduit necrosis. When gastric necrosis is suspected, the conduit and patient’s status must be monitored closely and the conduit resected if there is any evidence of full thickness necrosis. We do not recommend immediate reconstruction in this situation and a diversion should be performed by stapling off what, if anything, is left of the gastric conduit and constructing a cervical esophagostomy.

COLON

The colon is another option for esophageal reconstruction. Either the left or the right colon can be used for conduit creation. Both techniques employ the use of a portion of the transverse colon. Previous abdominal operations or colon pathology may exclude the use of the colon as an esophageal replacement. To assess the suitability of the colon, the surgeon must evaluate its blood supply and the presence of any pre-existing pathology preoperatively. The middle colic vessels provide the blood supply for a right colon conduit, whereas the ascending branch of the left colic provides the supply for a left colon conduit. The transverse colon portion of a left-sided conduit is supplied by the marginal arteries or the arc of Riolan. The colon as a conduit provides more length than is possible with the stomach and can be carried up as high as the pharynx when the blood supply is adequate. Some also believe the colon to be the better choice of conduit for patients with an extended life expectancy since the storage function of the stomach can be preserved. The consequences of an anastomotic leak are often less with a colon conduit since the anastomosis is always placed in the neck. It has also been suggested that over time the colonic conduit is able to generate propulsive forces to help with motility. The colon is resistant to peptic strictures and other late complications seen with a gastric conduit. Finally, the use of the colon maintains the reservoir function of the stomach in those in whom the stomach is not involved with the primary malignancy.

Preoperative evaluation of the colon is required in any patient in which the colon may be utilized as a conduit. Colonoscopy should be performed to rule out any primary colon lesions, significant diverticular disease, or vascular lesions. Alternatively, a double-contrast barium enema may also be obtained. A CT angiogram or MRA should also be obtained to verify the patency of major vessels on which the conduit may be based. A bowel regimen is also recommended preoperatively; a liquid diet for 48 hours prior to surgery is usually sufficient in clearing the colon of large amounts of stool which could hamper the procedure. Oral antibiotics no longer are routinely used as part of the bowel preparation having been supplanted by intravenous antibiotics at the time of surgery.

The procedure is begun by mobilizing either the right or left colon, depending on which is being used. Care should be taken not to injure any vessels in the transverse mesocolon when separating the colon from the omentum. Depending on which colon is to be used, the appropriate feeding vessel is identified via transillumination. The middle colic vessel is used for a right colon graft and the ascending branch of the left colic for a left colon transposition. While the left colon can be utilized as an isoperistaltic conduit, the right colon is positioned in an antiperistaltic orientation. The right colic artery is divided and the conduit is based on the middle colic allowing the proximal colon to be rotated into the neck. After deciding which vessels will be used, the mesentery is opened on the appropriate side of the middle colic vessel. An estimate of the length needed for transposition can be obtained by measuring the distance

from 5 cm below the xiphoid to the angle of the jaw with an umbilical tape. This length is sufficient if the conduit traverses the posterior mediastinum. If the retrosternal route is to be used, the measurement should extend to the earlobe.

from 5 cm below the xiphoid to the angle of the jaw with an umbilical tape. This length is sufficient if the conduit traverses the posterior mediastinum. If the retrosternal route is to be used, the measurement should extend to the earlobe.

Once the length of the graft is determined, temporary vascular isolation is obtained by placing bulldog clamps on the vessels that will be divided. Following this temporary occlusion, it is important to observe the graft for 5 to 10 minutes to assess for any evidence of ischemia or venous congestion. If the graft appears viable, then the appropriate vessels may be ligated. For a left colon graft, the middle colic artery is ligated at its origin from the superior mesenteric artery. For an antiperistaltic right colon graft, the right colic artery is ligated near its origin from the superior mesenteric artery. For an isoperistaltic right colon graft, an uncommon selection because of limitations in length, the middle colic artery is ligated, thus basing the graft on the right colic and advancing the distal end of the colon graft into the neck. Finally, the length of the colon needed is once again confirmed and then the colon is transected 1 cm beyond the remaining marginal vessels. The graft should now be free and ready for transposition.

The graft should be placed retrogastric and can transverse the mediastinum using either a posterior, anterior (retrosternal), or subcutaneous route. Delivery of the conduit through the mediastinum is facilitated using a sterile plastic bag (such as an intraoperative ultrasound bag) into which the conduit is placed for passage. This helps minimize damage to small vessels. When using the retrosternal or the subcutaneous route the hemimanubrium, adjoining clavicular head and medial first rib on the side of the anastomosis should be removed to provide a more natural lie for the conduit and some additional room. In addition, pressure on the mesocolon or conduit at this location can compromise either the arterial inflow or venous outflow and lead to congestion and potential anastomotic problems. Strictures will also form in this location if there is a constant pressure point on the conduit from the manubrium, clavicle, and first rib.

Advantages to using the colon as a conduit relate mostly to the ability to preserve the stomach. Since the stomach is not a part of the reconstruction, it can be resected for oncologic purposes if necessary such as when dealing with a Siewert type III gastroesophageal junction tumor with extensive involvement of the stomach. In addition, gastric reservoir function of the stomach can be maintained by leaving the native distal stomach in place. This can potentially aid in the resumption of normal dietary habits. Finally, the colon is also a barrier to reflux, providing some protection to the proximal esophagus from bile or acid reflux.

Disadvantages to using the colon relate mostly to the technical aspects related to the procedure. It can be a lengthy operation that requires three anastomoses (esophagocolic, gastrocolic, and colocolic). Also, up to 30% of patients ultimately will require reoperation after a colon conduit due to redundancy or dilation of the conduit. The development of significant redundancy presents as poor emptying of food into the stomach leading to stasis and dilation within the chest. The optimal time to prevent this complication is at the time of the initial operation by limiting any redundancy of the conduit and performing the cologastric anastomosis high on the posterior wall of the stomach. The length of conduit chosen and its final positioning within the chest must be precise and without excess to avoid a redundant conduit. Any additional length should be placed below the diaphragm and the conduit secured in such a position during the initial operation.

Additional complications associated with the use of the colon include those found with a gastric conduit. These include ischemia or necrosis of the conduit, anastomotic leaks, and stricture formation. Esophagocolonic anastomotic leaks require reoperation for repair less often than an esophagogastric anastomosis perhaps due to the less erosive nature of colonic secretions and its cervical location. Small leaks will often heal without operative intervention. The risk of gastrocolic reflux and peptic colitis can be reduced by placing the cologastric anastomosis high on the posterior portion of the stomach near the greater curvature. Additionally, a short segment of the conduit (8 to 10 cm) is positioned and secured in the infradiaphragmatic position near the hiatus to act as a barrier to reflux from the abdominal to the thoracic portion of the conduit.

JEJUNUM

The jejunum that is naturally resistant to both acid and bile offers a third choice for esophageal reconstruction. The abundant length and mesenteric vasculature of the jejunum make it another option for both long and short segment esophageal replacement. The vascular anatomy of the jejunal mesentery allows the graft to be supercharged using intrathoracic or cervical vessels anastomosed to jejunal vessels. This improves the arterial supply and venous drainage for the graft allowing greater reach.

Long Segment

Unlike the colon or the stomach, the existing vascular anatomy of the jejunum limits the length of a graft based solely on any one pedicle. Therefore, the technical aspects of creating a long segment jejunal interposition graft for esophageal replacement are centered around enhancing the collateral blood supply to the segment being transposed into the chest or neck. The proximal jejunum is evaluated and the arcading pattern of its vasculature assessed via transillumination (Fig. 21.2A). To use a segment of jejunum, the vascular arcade needs to have several main branches off of the superior mesenteric artery that feed the jejunum in continuous arcades. A segment with three to four sequential branches must be identified. These three to four arcades generally provide a length of up to 50 cm for transposition. The proximal two or three branches are divided while the distal vessel is left intact (Fig. 21.2B

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree