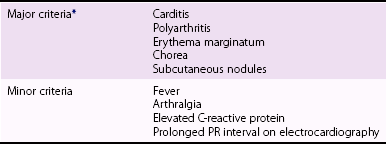

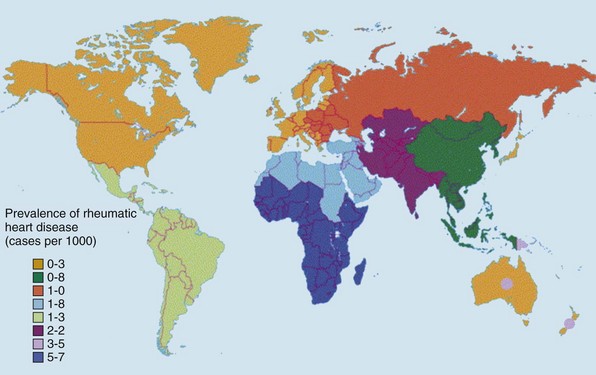

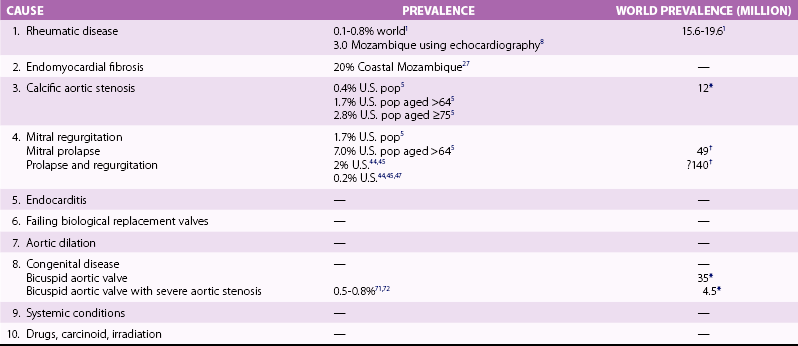

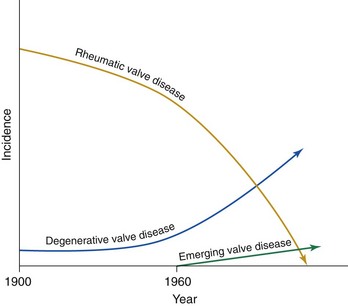

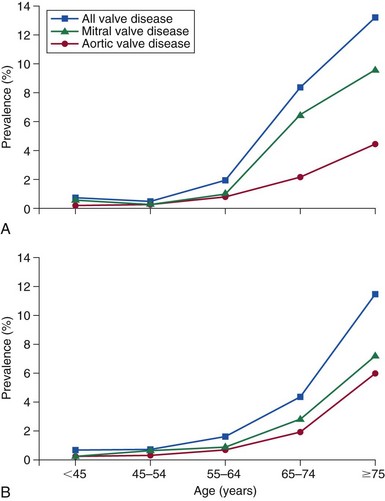

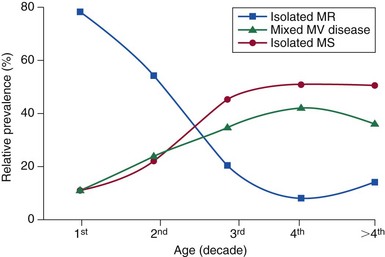

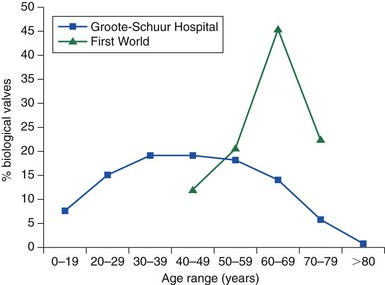

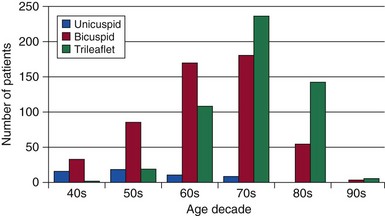

Chapter 1 Rheumatic fever is the most common cause of valve disease in the young, 1 but it predominates in industrially underdeveloped regions. These include Africa, India, the Middle East, South America, and parts of Australia and New Zealand, China, and Russia. 1 In developed countries, the incidence of rheumatic disease declined after the second half of the 20th century, although transient local resurgences still occur. 2 This decline was predominantly the result of improvements in living conditions and health care, as follows: • Improvements in living conditions: 3 • Improved access to health care • Treatment of streptococcal throat infections In addition there was a spontaneous reduction in the virulence of streptococcal serotypes, but it occurred after the incidence of rheumatic fever had already fallen. 4 These improvements in living conditions and health care have increased longevity so that valve conditions characteristic of old age now predominate ( Figure 1-1). Some 2.5% of the U.S. population has moderate or severe valve disease, but the prevalence rises after age 64 ( Figure 1-2) and is 13% in those older than 75. 5 Other studies confirm this age relationship.6,7 The contribution of old age to the world prevalence of valve disease is difficult to estimate precisely but probably now rivals that of rheumatic disease ( Table 1-1). The most common valve diseases in the elderly are: TABLE 1-1 Principal Causes of Valve Disease with Prevalence Where Known *The world population (pop) is 7 billion (7,000,000,000). The proportion aged over 60 years is about 10% 6 or 700,000,000. Assuming a prevalence of aortic stenosis of 1.74% in this age group gives a world prevalence of aortic stenosis of 12 million. The prevalence of bicuspid valve is 35 million based on a population prevalence of 0.5%. 71 In a study of patients with BAV of mean age 32 years at baseline followed for 20 years, 28 of 212 (13%) needed aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis.69,71 This finding suggests that around 4.5 million in the world could have severe aortic stenosis as a result of a bicuspid aortic valve, and the total, as a result of nonrheumatic disease, calcific stenosis in those aged >65 years and bicuspid aortic valve in those < 65 years, could be 16.5 million. †The world population is 7 billion (7,000,000,000). The proportion aged over 60 years is about 10% 126 or 700,000,000. Using the U.S. prevalence of mitral regurgitation of 7% in those aged >64 years would suggest a world prevalence of mitral regurgitation of 140 million. Applying the U.S. prevalence of mitral prolapse associated with regurgitation of 0.2% to the world population suggests a worldwide prevalence of mitral regurgitation of 140 million. The number with rheumatic disease may be subsumed within this number. FIGURE 1-1 Diagram illustrating changes in prevalence of valve disease in industrially developed countries. (Redrawn from Soler-Soler J, Galve E. Worldwide perspective of valve disease. Heart 2000;83:721–5.) FIGURE 1-2 Effect of age on prevalence of valve disease in three pooled population-based studies. • Calcific aortic valve disease • Aortic dilation causing aortic regurgitation • Functional mitral regurgitation as a result of left ventricular (LV) dysfunction Valve disease remains underdetected, 8 and there are major variations in the provision of health care in all countries of the world, including those that are industrially developed.9,10 This chapter reviews the causes of valve disease, describes variations in clinical care, and discusses ways in which the worldwide burden of disease could be reduced. The principal causes of valve disease and approximate prevalence are shown in Table 1-1. Genetically determined immune markers affect susceptibility to the initial infection and help determine the risk for development of chronic rheumatic disease.11,12 There is some evidence for disordered signaling mechanisms and reactivation of embryologic pathways. 13 Some streptococcal serotypes (emm types 3, 5, 6, 14, 18, 19, and 29) may be more likely than others to cause rheumatic fever. 11 These host and bacterial factors vary geographically. Rheumatic fever is uncommon after one episode of pharyngitis but occurs in up to 75% of patients experiencing recurrent episodes. Cardiac involvement occurs in 10% to 40% after the first attack of rheumatic fever 13 but more frequently after multiple attacks. 14 The development of chronic rheumatic disease depends on the age at the time of the acute episodes and their severity and frequency 15 and is more likely with multiple valve involvement, failure to obtain medical help, and lack of secondary prophylaxis.16,17 Single valve involvement and mitral stenosis are more likely in older individuals with less active carditis 14 ( Figure 1-3). FIGURE 1-3 Time-course analysis (by decades) of the relative prevalence of isolated mitral regurgitation (MR), mixed mitral valve disease, and isolated mitral stenosis (MS). (Redrawn from Marcus RH, Sareli P, Pocock WA, et al. The spectrum of severe rheumatic mitral valve disease in a developing country: correlations among clinical presentation, surgical pathological findings, and hemodynamic sequelae. Ann Intern Med 1994;120:177–83.) There is a proliferative exudative inflammation of the collagen of the valve and annulus characterized by the presence of modified histiocytes called Aschoff bodies. The valve, annulus, and chordae are edematous and inflamed, leading to annular dilation and chordal elongation. 15 In the long term, fibrosis and calcification develop. The Jones criteria guide the diagnosis of the first episode of rheumatic fever ( Table 1-2). 18 Likely rheumatic fever is defined by evidence of group A streptococcal infection (rising anti-streptolysin O (ASO) titers, positive results of culture or rapid antigen tests) and either two major criteria or one major with two minor criteria. For subsequent episodes in patients with established rheumatic disease, the World Health Organization (WHO) allows two minor criteria with evidence of a streptococcal infection including scarlet fever. The annual incidence of acute rheumatic fever worldwide is estimated at 471,000 cases, 1 on the basis of a metaanalysis of regional reports with a median incidence from 10 to 374 cases per 100,000 population ( Table 1-3). TABLE 1-3 Incidence of Acute Rheumatic Fever (Cases per 100,000 Population) From Carapetis JR. Rheumatic heart disease in developing countries. N Engl J Med 2007;357:439. Approximately 200,000 deaths per year occur from acute rheumatic fever or chronic rheumatic disease, mainly in children in developing countries. In Ethiopia, 20% of patients with rheumatic disease die before age 5 years, and 80% before 25 years. 17 In underdeveloped regions, 10% to 35% of all cardiac admissions are the result of acute or chronic rheumatic disease. 4 If one allows that 60% of patients with acute rheumatic fever experience chronic rheumatic disease, the annual incidence of new cases of chronic disease is estimated at 282,000. 1 However, there are major geographic differences, and the annual incidence in sub-Saharan Africa ranges from 1.0 to 14.6 per 1000 population. 19 The estimated annual incidence is 24 per 100,000 population in Soweto 20 but with a J-shaped age dependence, with 30 per 100,000 aged 15 to 19 years, 15 per 100,000 aged 20 to 29 years, and 53 per 100,000 older than 60 years. The worldwide prevalence of chronic rheumatic disease is estimated at 15.6 to 19.6 million. 1 There is wide geographical variation ( Figure 1-4), from approximately 0.8 to 7.9 per 1000 population in industrially underdeveloped regions1,21–23 to only 0.3 per 1000 in developed regions. 1 However, the prevalence rises sharply if echocardiography, rather than the more usual clinical screening, is used. In a study in Cambodia and Mozambique, 8 the prevalence was 2.3 per 1000 children indicated by clinical examination, but 28.1 per 1000 when echocardiography was used. Throughout Africa the prevalence is 1.0 to 6.9 per 1000 in studies using clinical diagnosis compared with 1.4 to 14.6 per 1000 in those using echocardiography. 19 The WHO criteria use valve regurgitation to define rheumatic disease. However, valve regurgitation can be physiological or may occur for other reasons, including myxomatous degeneration. Furthermore, early rheumatic changes may not cause regurgitation. Combined criteria using any grade of regurgitation associated with at least two morphological signs give a prevalence approximately four times that of the WHO criteria. 24 A new World Heart Federation consensus now categorizes definite or borderline rheumatic disease through the use of a combination of regurgitant severity, transvavlular gradient and valve morphology.25,25a Endomyocardial fibrosis (EMF) is, after rheumatic disease, the second most frequent cause of acquired heart disease in children and young adults in equatorial Africa. 26 Echocardiography of a sample of 1063 people in coastal Mozambique found a prevalence of 20% (95% confidence interval [CI] 17.4% to 22.2%). 27 EMF begins as a febrile illness, which is followed by a latent phase of 2 to 10 years. Symptoms then reappear as LV and right ventricular (RV) thrombi and fibrosis develop, leading to RV, LV, or biventricular restrictive cardiomyopathy and encasement of the mitral or tricuspid valves. The pathology of EMF is still uncertain. There is evidence for the reactivation of embryological pathways,13,28 and postulated etiological factors 27 that are not mutually exclusive include the following: • Hypereosinophilia: Features are similar to those of hypereosinophilic syndromes, and the eosinophil count is transiently high in some patients with EMF • Infection: EMF may be associated with helminths, schistosomiasis, filariasis, and malaria • Genetic predisposition: The incidence is high among some ethnic groups • Dietary: Eating uncooked cassava causes an EMF-like response in African green monkeys and may be relevant in humans, especially those with protein-deficient diets • Geochemical: Increased levels of cerium are found in the hearts of some patients with EMF living near the coast of Mozambique. The incidence and severity of aortic stenosis increase with age, but the process is not a passive, degenerative one. It involves active lipid deposition, inflammation, neoangiogenesis, and calcification (see Chapter 3).29,30 Aortic stenosis shares with other atherosclerotic processes a number of risk factors, including male gender, diabetes, dyslipidemia (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C] and low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C]), lipoprotein(a), metabolic syndrome, and smoking (see Chapter 4).31–37 Aortic valve sclerosis is defined by valve thickening with a peak transaortic velocity on echocardiography of less than 2.5 m/s. Around 16% of patients with sclerosis progress to having stenosis within 7 years. 38 Aortic valve sclerosis is also associated with cardiovascular disease and is a marker for a higher risk of myocardial infarction,32,39 particularly in patients with no established coronary disease 39 and those with low conventional risk profiles, such as women and patients younger than 55 years 40 (see Chapter 4). Age-related calcification can also affect the mitral annulus but rarely causes sufficient obstruction to require surgery, except occasionally in patients with chronic renal failure. 41 If calcification is found at both the aortic valve and mitral annulus but also in the aorta, then there is a significant likelihood of associated three-vessel coronary disease. 42 The chordae are prone to stretching and rupture and may be deficient, particularly at the commissures or at the middle scallop of the posterior leaflet (See Chapter 18). There is either myxomatous infiltration or fibroelastic deficiency, but the degree of histological abnormality varies. 43 Myxomatous infiltration causes irregular thickening of the leaflets as seen on the echocardiogram. Prolapse associated with myxomatous degeneration has a genetic component and is more common in Marfan syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV. Fibroelastic deficiency is more common in the elderly. Methods of defining prolapse have been refined with advances in echocardiography and particularly with the realization that the mitral annulus is saddle shaped. The prevalence of prolapse, using strict criteria, is around 2%44,45 and is associated with tricuspid prolapse in 10% of cases 46 or, more rarely, with aortic valve prolapse. Mitral regurgitation occurs in about 9% of cases with prolapse. 47 The grade of regurgitation depends on the degree of leaflet thickening and prolapse and is worse when ruptured chordae lead to flail or partially flail leaflet segments. In patients with these findings, the mean 10-year survival without heart failure is only 37%. 48 The use of the terms ischemic, secondary, and functional is not fully standardized. Ischemic disease is an important cause of functional mitral regurgitation, but ischemic regurgitation is usually used for acute ischemic mitral regurgitation as a result of papillary muscle rupture. This condition requires emergency surgery (see Chapter 19). The cause of LV dysfunction leading to functional mitral regurgitation reflects the causes of heart failure, which vary geographically. Important causes are ischemic disease, hypertension, and alcohol use in the West and Chagas disease and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)4,23 globally. In South Africa, subvalvar aneurysms below the mitral valve cause regurgitation, embolization, and rupture.49,50 These problems may occur because of a congenital weakness of the tissue around the atrioventricular groove. The incidence of infective endocarditis is between 3 and 10 episodes per 100,000 patient-years, 51 but there are major geographical variations depending largely on the age of the population and the frequency of medical devices or intravenous (IV) drug use. 52 The incidence increases with age and is 14.5 episodes per 100,000 patient-years in those aged 70 to 80 years. 51 There is a male-to-female ratio of more than 2 : 1 (see Chapter 25). 51 In the industrially underdeveloped regions, patients with endocarditis are young, about three quarters have rheumatic heart disease, and oral streptococci are the main infecting organisms. 53 The risk of endocarditis is about five times that of the general population, particularly in the presence of a murmur, for which the risk is 1 case in 1400 patient-years. 54 However, in fully industrialized regions, most patients are older and endocarditis is increasingly associated with replacement heart valves, pacemakers,55–57 or hemodialysis. 58 Patients with prosthetic valves have a 50 times higher risk of endocarditis than the rest of the population, 59 with early infection—within one year of implantation—usually caused by coagulase-negative staphylococci or Staphylococcus aureus60 and late infection by oral commensals. Pacemakers are usually infected with S. aureus or coagulase-negative staphylococci. 57 In a separate, much younger, group, endocarditis is caused by intravenous drug use, with S. aureus as the most common infecting organism. Predisposing factors are diabetes 58 and immune deficiency including HIV. 4 Biological valves have acceptable durability in older patients; failures are uncommon before 5 years in the mitral position and before 8 years in the aortic position.60,61 However, durability is limited in younger patients, particularly those younger than 40 years old.61,62 The main advantage of biological valves is that anticoagulation is not required. Mechanical valves are expected to have unlimited durability but require anticoagulation usually with warfarin. In general, in industrially developed regions, biological valves are implanted in the relatively older patient, typically older than 65 years, and mechanical valves are used in younger patients (see Chapter 26). However, biological valves are implanted in younger patients 61 if anticoagulation control may be uncertain or to allow pregnancy without the potential teratogenic and bleeding complications of oral anticoagulants. This practice is common in industrially underdeveloped countries ( Figure 1-5) so “redo” surgery is frequently necessary. At the Heart Institute in São Paulo, Brazil, the mean age at surgery is 49 years, and 41% of procedures are redo operations. 23 This is also a problem in developed countries because patients survive longer. 63 FIGURE 1-5 Diagram comparing the proportion of biological valves expressed as a percentage of total implants in an industrially developed and underdeveloped region. In the United Kingdom, 7% of aortic valve operations are redo procedures. 64 Furthermore there is a trend toward implantation of younger patients with biological valves. In the United Kingdom, for patients between 56 and 60 years of age, the proportion of isolated aortic valve replacement operations using biological valves increased from 25% in 2004 to 40% in 2008. This increase results partly from the perceived longer durability of third-generation biological valves and partly from the possibility of a valve-in-valve transcatheter procedure to treat primary failure. 65 Bicuspid aortic valve should be regarded as a general thoracic aortopathy and is associated with significant dilation of the aorta to more than 40 mm due to medial necrosis 66 in about 20% of cases, 67 in approximately one half affecting the root and in the other half the ascending aorta. Aortic dilation is more likely with associated coarctation, 68 but dissection is relatively uncommon and has a relatively high operative success probably because of the youth and underlying good health of the subjects. Prophylactic surgery is necessary in about 5% during a 20-year follow-up (see Chapter 13). 69 Congenital lesions account for approximately 5% of valve operations throughout the world. Bicuspid aortic valve is the most common abnormality, affecting up to 2.0% of the population based on autopsy series 70 but 0.5% to 0.8% in larger population-based studies.71,72 There is evidence of geographic clustering of cases, 73 which is likely as a result of genetic factors74,75; the risk of a bicuspid aortic valve or aortic disease is about 10% in first-degree relatives of probands.76,77 The ratio of male to female is approximately 2 : 1. The valve is “anatomically” or truly bicuspid in one third of cases and “functionally” bicuspid in two thirds as a result of incomplete separation of two cusps in utero. The most common pattern, in 80% of cases, is failure of right-left separation, which is more likely to be associated with aortic dilation. 78 Failure of separation of right and noncoronary cusps is more likely to be associated with mitral prolapse. 78 During a 20-year follow-up, 24% of patients with a bicuspid aortic valve demonstrated severe stenosis or regurgitation requiring surgery. 69 Events are far more common in those with even mild valve thickening at baseline, with surgical rates of 75% at 12 years in the presence of thickening compared with only 8% in the absence of thickening. 69 Because the young are more likely to have surgery, the frequency of bicuspid disease is around one third of unselected surgical cases. 79 However, in detailed pathological examination of surgically excised valves, the proportion of bicuspid valves in patients with aortic stenosis having surgery ranges from 67% in patients in their 40s 80 to 28% in octogenarians ( Figure 1-6).81–87 FIGURE 1-6 Numbers of cusps by decade of age in patients undergoing aortic valve surgery for aortic stenosis.

Epidemiology of Valvular Heart Disease

A, Graph of pooled echocardiography data available from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) database from three population-based studies: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, and the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS). In total there were 11,911 subjects who had undergone echocardiograms, 40% black and 59% white. These data were compared with the Olmsted county echocardiography register (B) in which echocardiograms were performed for clinical reasons. The population-based prevalence of all moderate or severe valve disease was 5.2%, which, when corrected for the age and sex distribution of the U.S. population at the time of the data collection in 2000, was 2.5% (95% confidence interval 2.2-2.7%). The prevalence rose after age 64 years and was 13.2% after age 74. (Redrawn from Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, et al. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet 2006;368:1005–11.)

Causes of Valve Disease

Rheumatic Disease

Endomyocardial Fibrosis

Calcific Aortic Stenosis

Mitral Regurgitation

Mitral Prolapse

Functional Mitral Regurgitation

Endocarditis

Failing Biological Valves

The blue line illustrates data from Groote-Schuur Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. The green line illustrates data from a European center. (Redrawn from Zilla P, Brink J, Human P, Bezuidenhout D. Prosthetic heart valves: catering for the few. Biomaterials 2008;29:385–406.)

Aortic Dilation

Congenital Disease

Excised valves were examined in detail by a cardiac pathologist. The proportions with a bicuspid aortic valve were, by decade of age: 67% in the 40s; 57% in the 50s; 59% in the 60s; 42% in the 70s; 28% in the 80s; and 33% in the 90s. (Data from references 81 through 87.)![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Epidemiology of Valvular Heart Disease

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue