EPIDEMIOLOGY OF CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is now the most common cause of death worldwide. Before 1900, infectious diseases and malnutrition were the most common causes and CVD was responsible for less than 10% of all deaths. Today, CVD accounts for approximately 30% of deaths worldwide, including nearly 40% in high-income countries and about 28% in low- and middle-income countries.

THE EPIDEMIOLOGIC TRANSITION

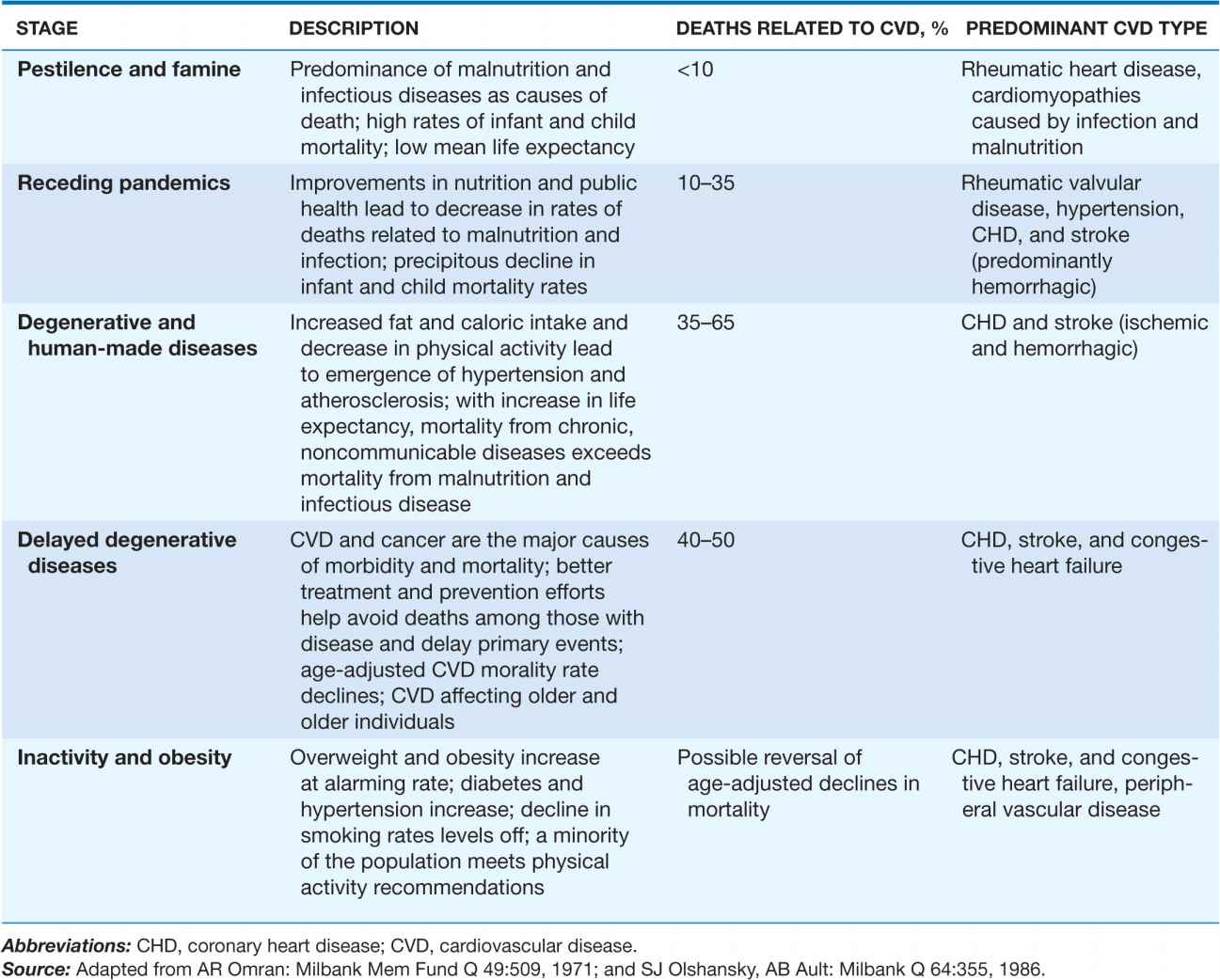

The global rise in CVD is the result of an unprecedented transformation in the causes of morbidity and mortality during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Known as the epidemiologic transition, this shift is driven by industrialization, urbanization, and associated lifestyle changes and is taking place in every part of the world among all races, ethnic groups, and cultures. The transition is divided into four basic stages: pestilence and famine, receding pandemics, degenerative and human-made diseases, and delayed degenerative diseases. A fifth stage, characterized by an epidemic of inactivity and obesity, may be emerging in some countries (Table 2-1).

TABLE 2-1

FIVE STAGES OF THE EPIDEMIOLOGIC TRANSITION

Malnutrition, infectious diseases, and high infant and child mortality rates that are offset by high fertility mark the age of pestilence and famine. Tuberculosis, dysentery, cholera, and influenza are often fatal, resulting in a mean life expectancy of about 30 years. Cardiovascular disease, which accounts for less than 10% of deaths, takes the form of rheumatic heart disease and cardiomyopathies due to infection and malnutrition. Approximately 10% of the world’s population remains in the age of pestilence and famine.

Per capita income and life expectancy increase during the age of receding pandemics as the emergence of public health systems, cleaner water supplies, and improved nutrition combine to drive down deaths from infectious disease and malnutrition. Infant and childhood mortality rates also decline, but deaths due to CVD increase to between 10% and 35% of all deaths. Rheumatic valvular disease, hypertension, coronary heart disease (CHD), and stroke are the predominant forms of CVD. Almost 40% of the world’s population is currently in this stage.

The age of degenerative and human-made diseases is distinguished by mortality from noncommunicable diseases—primarily CVD—surpassing mortality from malnutrition and infectious diseases. Caloric intake, particularly from animal fat, increases. Coronary heart disease and stroke are prevalent, and 35–65% of all deaths can be traced to CVD. Typically, the rate of CHD deaths exceeds that of stroke by a ratio of 2:1 to 3:1. During this period, average life expectancy surpasses 50 years. Roughly 35% of the world’s population falls into this category.

In the age of delayed degenerative diseases, CVD and cancer remain the major causes of morbidity and mortality, with CVD accounting for 40% of all deaths. However, age-adjusted CVD mortality declines, aided by preventive strategies such as smoking cessation programs and effective blood pressure control, acute hospital management, and technological advances such as the availability of bypass surgery. CHD, stroke, and congestive heart failure are the primary forms of CVD. About 15% of the world’s population is now in the age of delayed degenerative diseases or is exiting this age and moving into the fifth stage of the epidemiologic transition.

In the industrialized world, physical activity continues to decline while total caloric intake increases. The resulting epidemic of overweight and obesity may signal the start of the age of inactivity and obesity. Rates of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and lipid abnormalities are on the rise, trends that are particularly evident in children. If these risk factor trends continue, age-adjusted CVD mortality rates could increase in the coming years.

THE EPIDEMIOLOGIC TRANSITION IN THE UNITED STATES

The United States, like other high-income countries, has proceeded through four stages of the epidemiologic transition. Recent trends, however, suggest that the rates of decline of some chronic and degenerative diseases have slowed. Because of the large amount of available data, the United States serves as a useful reference point for comparisons.

The age of pestilence and famine (before 1900)

The American colonies were born into pestilence and famine, with half the Pilgrims who arrived in 1620 dying of infection and malnutrition by the following spring. At the end of the 1800s, the U.S. economy was still largely agrarian, with more than 60% of the population living in rural settings. By 1900, average life expectancy had increased to about 50 years. However, tuberculosis, pneumonia, and other infectious diseases still accounted for more deaths than any other cause. CVD accounted for less than 10% of all deaths.

The age of receding pandemics (1900–1930)

By 1900, a public health infrastructure was in place: Forty states had health departments, many larger towns had major public works efforts to improve the water supply and sewage systems, municipal use of chlorine to disinfect water was widespread, pasteurization and other improvements in food handling were introduced, and the educational quality of health care personnel improved. Those changes led to dramatic declines in infectious disease mortality rates. However, the continued shift from a rural, agriculture-based economy to an urban, industrial economy had a number of consequences on risk behaviors and factors for CVD. Owing to a lack of refrigerated transport from farms to urban centers, consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables declined and consumption of meat and grains increased, resulting in diets that were higher in animal fat and processed carbohydrates. In addition, the availability of factory-rolled cigarettes made tobacco more accessible and affordable for the mass population. Age-adjusted CVD mortality rates rose from 300 per 100,000 people in 1900 to approximately 390 per 100,000 during this period, driven by rapidly rising CHD rates.

The age of degenerative and human-made diseases (1930–1965)

During this period, deaths from infectious diseases fell to fewer than 50 per 100,000 per year and life expectancy increased to almost 70 years. At the same time, the country became increasingly urbanized and industrialized, precipitating a number of important lifestyle changes. By 1955, 55% of adult men were smoking, and fat consumption accounted for approximately 40% of total calories. Lower activity levels, high-fat diets, and increased smoking pushed CVD death rates to peak levels.

The age of delayed degenerative diseases (1965–2000)

Substantial declines in age-adjusted CVD mortality rates began in the mid-1960s. In the 1970s and 1980s, age-adjusted CHD mortality rates fell approximately 2% per year and stroke rates fell 3% per year. A main characteristic of this phase is the steadily rising age at which a first CVD event occurs. Two significant advances have been credited with the decline in CVD mortality rates: new therapeutic approaches and the implementation of prevention measures. Treatments once considered advanced, such as angioplasty, bypass surgery, and implantation of defibrillators, are now considered the standard of care. Treatments for hypertension and elevated cholesterol along with the widespread use of aspirin have also contributed significantly to reducing deaths from CVD. In addition, Americans have been exposed to public health campaigns promoting lifestyle modifications effective at reducing the prevalence of smoking, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.

Is the United States entering the fifth age?

The decline in the age-adjusted CVD death rate of 3% per year through the 1970s and 1980s tapered off in the 1990s to 2%. However, CVD death rates declined by 3–5% per year during the first decade of the new millennium. In 2000, the age-adjusted CVD death rate was 341 per 100,000. By 2006, it had fallen to 263 per 100,000. Competing trends appear to be in play. On the one hand, the well-recognized increase in the prevalence of diabetes and obesity, a slowing in the rate of decline of smoking, and a leveling off in the rate of detection and treatment for hypertension are in the negative column. On the other hand, cholesterol levels continue to decline in the face of increased statin use.

CURRENT WORLDWIDE VARIATIONS

An epidemiologic transition much like that which occurred in the United States is occurring throughout the world, but unique regional features have modified aspects of the transition in various parts of the world. In terms of economic development, the world can be divided into two broad categories, (1) high-income countries and (2) low- and middle-income countries, which can be further subdivided into six distinct economic/geographic regions. Currently, 85% of the world’s population lives in low- and middle-income countries, and it is those countries which are driving the rates of change in the global burden of CVD (Fig. 2-1). Three million CVD deaths occurred in high-income countries in 2001, compared with 13 million in the rest of the world.

An epidemiologic transition much like that which occurred in the United States is occurring throughout the world, but unique regional features have modified aspects of the transition in various parts of the world. In terms of economic development, the world can be divided into two broad categories, (1) high-income countries and (2) low- and middle-income countries, which can be further subdivided into six distinct economic/geographic regions. Currently, 85% of the world’s population lives in low- and middle-income countries, and it is those countries which are driving the rates of change in the global burden of CVD (Fig. 2-1). Three million CVD deaths occurred in high-income countries in 2001, compared with 13 million in the rest of the world.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree