Endovascular Interventions for Paget–Schroetter/Venous Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Mitchell W. Cox

Cynthia K. Shortell

Venous thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is an uncommon problem which is definitively addressed with a surgical approach to thoracic outlet decompression, typically first rib resection. Most of the surgical literature on treatment of venous TOS addresses endovascular intervention only tangentially as a prelude to operative intervention, since the etiology is external compression of the vein and not intraluminal pathology. There is, however, an important role for endovascular procedures before, during, and potentially after the surgical procedure. Salvage of a patent subclavian vein in these patients may be extremely challenging, and judicious application of appropriately timed endoluminal interventions is critical to maximize the odds of success.

When confronted with a young, otherwise healthy patient who has an upper extremity deep venous thrombosis (DVT), venous TOS will be very high on the differential, and very little additional testing is required before moving to definitive therapy. After confirmation of the thrombosis by duplex, venography with catheter-directed thrombolysis is indicated. There is typically a window of roughly 4 to 6 weeks after symptom onset to salvage a patent subclavian vein, and most good-risk patients should be offered thrombolysis and rib resection if they present in this time period.

In cases where the presentation is very late, one would expect lower odds of success with thrombolysis, and if symptoms are mild, conservative management with systemic anticoagulation alone may be considered. If symptoms are more severe, however, venogram with a trial of thrombolytic is still reasonable even if presentation is delayed. There may well be acute thrombus along with more chronic organized clot, and it is difficult to predict which patients will have a salvageable vein without performing a venogram and a trial of thrombolytics. Some patients may do well over the long term with anticoagulation alone; however, many will have persistent symptoms, and this may be a significant

problem for young, active individuals. For this reason, we offer venography and attempted lysis for nearly all patients presenting with a clinical picture consistent with venous TOS.

problem for young, active individuals. For this reason, we offer venography and attempted lysis for nearly all patients presenting with a clinical picture consistent with venous TOS.

Endovascular treatment with prolonged lytic infusion is contraindicated in patients who may be at risk for significant bleeding complications, including patients with recent major surgery, recent stroke, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, or severe trauma. Mechanical thrombolysis, with local tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) infusion using a rheolytic thrombectomy (Angiojet, Medrad, Warrendale, PA) device, or a pharmacomechanical system (Trellis, Covidien, Mansfield, MA) may be an option for patients with contraindications to lytic infusion. Patients with axillosubclavian DVT due to indwelling venous lines or pacemaker leads are not typically good candidates for endovascular intervention and should usually be offered anticoagulation alone with possible removal of the offending central line.

Very little in the way of preoperative testing is required before proceeding to the endosuite for venogram and lysis. The combination of clinical history and upper extremity venous duplex are usually diagnostic, and we have found studies such as magnetic resonance venography (MRV) and computed tomography venography (CTV) to be of little clinical utility, although they may demonstrate the extent of thrombosis. Very rarely, we have had patients with chronic arm swelling but no documented DVT, or continued arm swelling after a poorly executed first rib resection, who may benefit from a more elective work-up with diagnostic imaging and CTV or MRV to assess for other pathology before committing to venogram and lysis. A work-up for hypercoagulable states is often ordered early in the course; however, the results rarely influence the initial approach to treatment, and after sending the appropriate laboratory studies for hypercoagulability, one may proceed with endovascular intervention.

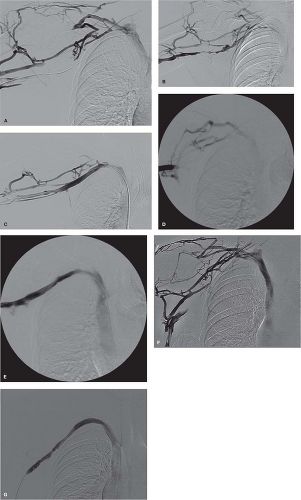

During the initial procedure, the brachial or basilic vein is punctured with duplex guidance, and a 5- or 6-Fr sheath is placed (Fig. 11.1). At the time of initial venography, an axillary/subclavian thrombosis and significant collateral filling will usually be visualized, with a normal brachiocephalic vein and superior vena cava (SVC) (Fig. 11.2A). Crossing the acute thrombus in the axillary vein with a wire and catheter is almost always easy, but crossing the subclavian vein in the thoracic outlet may be difficult, given underlying chronic damage to the vein with stenosis, scarring, and intraluminal webs and bands. In cases of chronic subclavian vein occlusion which cannot be crossed with a wire, thrombolysis is unlikely to be successful at reopening the chronic occlusion, and simple anticoagulation may be considered. Lysis of associated acute thrombus in

such cases is likely to produce some symptomatic improvement (Fig. 11.3); however, the benefits of first rib resection in such cases are very unclear.

such cases is likely to produce some symptomatic improvement (Fig. 11.3); however, the benefits of first rib resection in such cases are very unclear.

If the subclavian vein can be successfully traversed, thrombolysis will likely be effective. At this point, simple placement of a lytic catheter (Fig. 11.4) with 12 to 24 hours of TPA infusion at 0.5 to 1 mg/hr is reasonable; however, there are now several adjuncts which may speed up the clot lysis time, including percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy (Angiojet, Trellis) and ultrasound-accelerated thrombolysis (EKOS Corporation, Bothell, WA). Acute thrombus may be lysed within 12 to 24 hours, even with an infusion catheter alone, but frequently, there is a mix of acute and chronic thrombus which may require 48 to 72 hours of lysis, even with these adjuncts.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree