The most important endovascular consideration is that endovascular techniques are replacing open surgery. Endovascular techniques and concepts must be integrated into vascular practice to best serve the patient. An arbitrary division of labor that divides open and endovascular techniques between specialists of different disciplines introduces a profound discontinuity in vascular care. The most effective vascular specialist is able to provide a full spectrum of treatment options. Vascular disease management appears to be approaching an era in which endovascular surgery will be the treatment of choice for most situations requiring mechanical intervention, with open surgery reserved for endovascular failures and for those patients with the most diffuse patterns of disease. Endovascular surgery has influenced the care of disease in every vascular bed. The complications and failures of endovascular procedures can often be solved with endovascular techniques, and it does not automatically mean open surgery is required. Reducing periprocedural morbidity and managing threatening illness with less invasive approaches has proven to be a worthwhile endeavor. The purpose of this chapter is to provide perspective on the role of endovascular techniques and the many factors that contribute to the success of the endovascular surgeon.

The Development of Endovascular Surgery

There has been a substantial increase in awareness of minimally invasive surgery and its benefits across all surgical specialties. Patients, primary care physicians, and specialists have come to expect the development and the benefits of this change in approach to mechanical intervention in all organ systems.

Numerous factors have promoted the maturation of endovascular surgery. A change in attitude has occurred among vascular specialists over the past decade about the utility and potential benefit of endovascular techniques. Endovascular skills have steadily improved among vascular surgeons, and these skills are being used to solve vascular problems. Vascular surgeons have recognized the need for endovascular inventory and imaging equipment as essential tools for success. There has been continuous improvement in technology and in the tools available for the treatment of vascular disease through endoluminal manipulation (

Table 2-1). Preoperative imaging methods, including duplex mapping and magnetic resonance arteriography, help to select patients for endovascular therapy. While open vascular surgery may experience further small incremental refinements in the years to come, the rapid development of endovascular technology is on a steep trajectory of continued major improvements as additional skills and technology are rapidly put into clinical practice.

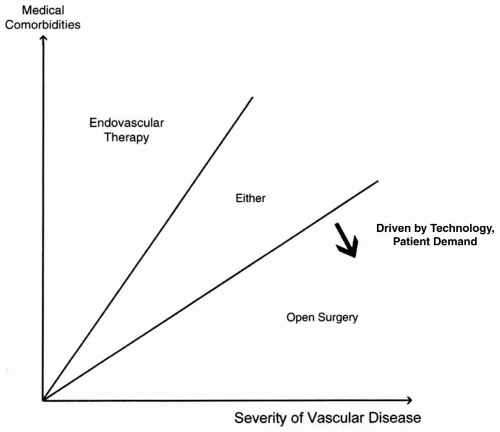

As recently as a decade ago, endovascular techniques could only be used to treat the most focal lesions. This translated clinically into a situation where these procedures worked best in the patients who needed them least. Open surgery was employed for patients with any degree of disease complexity. Many of the patients with severe medical comorbid conditions who were not candidates for open surgery also had diffuse patterns of disease and could not be treated. The development of stents (for occlusive disease) and stent-grafts (for aneurysmal disease) has changed that. Now many more complex patterns of disease can be managed with endovascular techniques. Driven by advancing technology and patient demand, many who would have been treated with open surgery in the past are being treated with endovascular surgery (

Fig. 2-1).

The Role of Endovascular Therapy in Various Vascular Beds

Orifice lesions, complex stenoses, occlusions, embolizing lesions, and aneurysms can be treated with current technology. Occlusive disease of the carotid, subclavian, visceral, renal, aortoiliac, femoral—popliteal, and tibial segments can be treated

in many patients with a combination of balloon angioplasty and stents. Aneurysms of the thoracic and abdominal aorta and peripheral arteries can be treated now that stent-grafts are available. Smaller sidebranch aneurysms can be treated with coil embolization. Endovascular surgery is now the primary mode of therapy for many disease presentations, including renal artery stenosis, aortoiliac occlusive disease, and in many patients with infrainguinal occlusive disease, aortoiliac aneurysms, and arterial injuries. The only major vascular bed where endovascular intervention has not played a prominent role in treatment is the extracranial cerebrovascular circulation. Carotid bifurcation balloon angioplasty and stenting remains under intense study. As the results of carotid stent trials become available, carotid bifurcation stenting will likely become the treatment of choice for many patients with carotid stenosis.

With the development of stents and stent-grafts has come the ability to extend endovascular solutions to treat many of these lesions without a significant incidence of immediate failure, emergency open repair, or a worsening of the clinical condition. In the near future drug-eluting stents and stent-grafts with side branches may also reach clinical utility. Other likely developments will come in the form of miniaturization of devices, pharmacologic adjuncts, less toxic contrast agents, alternative methods of recanalization, lower profile stent-grafts, and customized stent designs.

The long-term outcomes of many newer endovascular procedures are not yet known, and there are likely to be varying levels of durability for these procedures. This factor makes patient selection a key issue. Nevertheless, it is likely that within 5 years, the majority of noncoronary vascular disease requiring mechanical treatment will be considered for endovascular intervention as the treatment of choice. Open arterial surgery will be reserved for endovascular failures, the most severe patterns of occlusive and aneurysmal disease, and new dialysis access. In effect, cases with the worst prognostic factors will be relegated to open surgery.

How to Obtain Endovascular Skills

Obtaining and developing endovascular skills is different from the qualifications needed for obtaining hospital privileges to perform endovascular procedures. Qualifications for privileges represent a minimum standard, while the development of endovascular skills is a moving target as new technology is developed. Basic endovascular skills that form the foundation of the field are listed in

Table 2-2 and are discussed later in this chapter. As techniques develop, new skills must be added that provide options for performing endovascular therapy (

Table 2-3). An important complement to developing endovascular skills is a familiarity with the inventory and the various tools available for usage with respect to guidewires, catheters, access techniques, and various methods of revascularization. Inventory issues are discussed later in this chapter.

Pathways to obtaining endovascular skills are listed in

Table 2-4. Most vascular fellowships include sophisticated endovascular training. Multiple other pathways to skill development exist for vascular specialists who were trained in the era before endovascular training was part of fellowship. The best option for the established practitioner who requires training in endovascular techniques is the endovascular fellowship. This is usually a 3-month commitment to training at an institution with a strong endovascular program. The Society for Vascular Surgery has established an accreditation process for endovascular fellowships.

The number of endovascular cases that an individual should perform to achieve competence varies from one person to the next based upon previous vascular experience, interest and enthusiasm, eye-fluoro-hand coordination, and other factors. Although the learning curve for endovascular skills varies from one surgeon to another, surgeons are uniquely qualified to develop these skills due to familiarity with the anatomy, pathology, natural history of vascular disease, other treatment options, and the individual patients. Basic skills can be used to treat iliac and superficial femoral arteries and to place vena cava filters. Complex aortic or tibial angioplasty requires a more developed skill set. Renal and carotid stenting may be even more challenging because they involve remote access, short distance runoff (to anchor a guidewire), and unforgiving end organs. When endovascular interventions are performed as part of a vascular practice, the vascular surgeon is competing with all other specialists who desire to perform endovascular interventions as well. In this setting, the surgeon must be able to demonstrate excellent skills, satisfactory results, and the rational and deliberate incorporation of new techniques.

One key pathway to obtaining endovascular skills is the potential to use fluoroscopic imaging and endovascular techniques as an adjunct to open surgery (

Table 2-5). Many of the commonly performed open procedures can be improved by completion arteriography, fluoroscopy to guide catheter placement, or inflow or outflow balloon angioplasty. Fluoroscopically guided catheter manipulation and interval arteriography are especially useful during the operative management of acute limb ischemia. Endovascular procedures may also be performed in the operating room at the same time as a planned open procedure. Vena cava filter placement may be performed at the time of orthopedic or trauma operations. Patients may be selected for lower extremity bypass using duplex or magnetic resonance angiography, and confirmatory catheter-based angiography may be performed at the time of surgery. As these adjuncts become integrated into the treatment algorithms, they are likely to be used more often.

Another challenge is to continue to improve and update one’s skills after a certain minimum level of expertise has been attained. This maintenance of skill requires vigilance and enthusiasm, including attention to inventory, formal continuing medical education, attention to the materials and methods of the various journals, taking notes at meetings, and developing a network of colleagues who can discuss a case or evaluate x-rays sent over the Internet, as well as confer when a difficult problem arises. As is the case with open surgery, endovascular cases must be performed on a regular basis to maintain skills.

Qualifications to Perform Endovascular Procedures

Hospital privileges to perform procedures are granted by the credentials committee of each institution. Criteria for granting privileges vary significantly between hospitals. Many hospitals have documented criteria for endovascular procedures, and the individual practitioner must check with the institution about the specific requirements.

The granting of privileges to perform endovascular procedures has been a contentious issue. The training and approach of the various disciplines that want to treat vascular disease differ from one discipline to the other. Therefore, set case numbers have been recommended by several national societies to serve as minimum requirements. In establishing criteria for endovascular privileges, the use of external standards, such as published requirements by various societies, may be used by hospital credentials committees to set standards (

Table 2-6).

Specific requirements for endovascular procedures regarding privileges should be specifically stated within the credentialing documents for each vascular department. A set of standards is established within each hospital for granting requested privileges to perform carotid endarterectomy, abdominal aortic aneurysm, lower extremity bypass, and other open vascular procedures. The same mechanism should be employed for endovascular privileges. Regardless of the arbitrary minimum requirements, the goal for vascular surgeons should be to set a high standard as specialists in the field of vascular disease and to exceed that standard in routine practice.

Vascular surgery differs from most other disciplines in the following important way that relates to the issue of qualifications to perform vascular procedures. Contrary to other surgical specialties, there is no single procedure that is the exclusive domain of the vascular specialty. Vascular surgeons are accustomed to competing with other specialists for all open and endovascular surgery (

Table 2-7). The one important difference between vascular specialists and others who would like to include the vascular system in their work is that vascular is the only specialty that can provide the entire spectrum of care. To the extent that

vascular surgeons are able to master and deliver all therapeutic modalities, including endovascular approaches, we fulfill our responsibility to the patients for complete vascular care. To the extent that this responsibility is abdicated, haphazard and discontinuous care is the likely result.