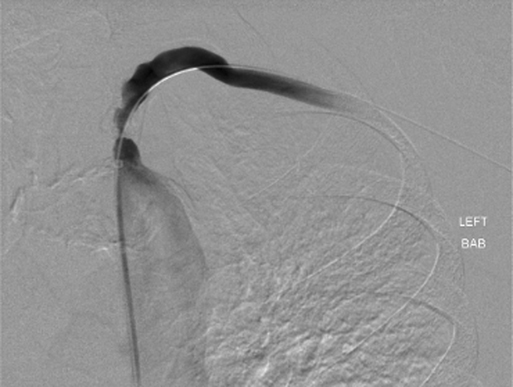

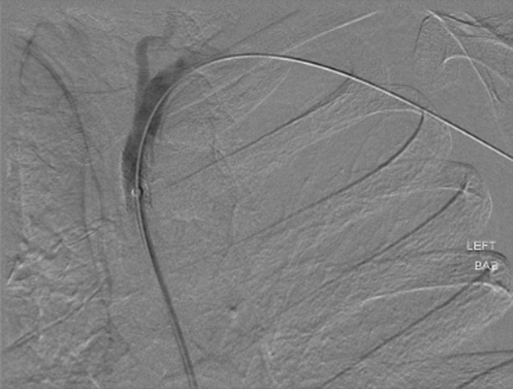

Contrast injections at 15 to 20 mL/second, for a total injection of 30 to 40 mL, are routine. Evaluation of the great vessels should include type of aortic arch, degree of aortic disease, and status of contralateral vertebral artery. The length and severity of subclavian artery stenosis should be assessed, along with the proximity of the lesion to the vertebral and internal mammary arteries (Figure 1). Selective catheterization can be performed with a variety of catheters, based on the preference of the interventionalist and the type of aortic arch. Critical ostial stenosis should be predilated to allow safe advancement of a balloon-expandable stent across the lesion. The sheath should then be advanced just distal to the lesion (Figure 2). Ostial lesions are best treated with balloon-expandable stents and should be sized 1:1 with the native artery. Oversizing in this setting can result in arterial perforation. If the surgeon is unsure of the size of the native artery, intravascular ultrasound can be used to obtain a measurement. After the balloon-expandable stent is advanced to the end of the sheath, the sheath is withdrawn into the aortic arch, leaving the stent across the lesion. Only 2 mm of the proximal stent should protrude within the arch of the aorta. If the protrusion of the proximal stent is too long, this can limit future repeat interventions and can pose a hazard with future coronary catheterizations. Currently, there is no Federal Drug Administration–approved stent for use specifically in the subclavian artery, and off-label use is required if primary stenting is chosen or needed if an inadequate angioplasty is achieved.

Endovascular Angioplasty and Stenting for Proximal Subclavian Artery Stenosis

Technical Principles of Endovascular Therapy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine