Endoscopy of the Esophagus

Richard Lazzaro

Joseph LoCicero III

Endoscopic evaluation of the esophagus has become the accepted standard for assessing and diagnosing both mucosal and structural diseases of the esophagus. Current-generation small-diameter video endoscopes provide high-resolution images, improved flexibility, and more comfortable insertion. Some endoscopists will order a barium esophagogram before endoscopy, especially in patients with dysphagia, but endoscopy is increasingly being used as the first step in the evaluation of esophageal disease. However, in patients with symptoms suggestive of a Zenker’s diverticulum, a barium esophagogram is a more sensitive diagnostic technique.

In addition to improved diagnostic capabilities, endoscopes can provide such therapeutic options as variceal band ligation, suturing, and mucosal resection. Endoscopic ultrasound has added a second dimension to evaluating the esophageal wall and the paraesophageal structures. Endoscopic ultrasound also permits directed fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of esophageal and paraesophageal lesions. Ultrasonic miniprobes are available for insertion through endoscope biopsy channels for strictured lesions where passage of the diagnostic endoscopic ultrasound is impossible.

For diagnostic esophagoscopy, one must identify both normal and abnormal structures. Therapeutic esophagoscopists require an understanding of stricture and achalasia dilation, botulinum toxin injection, foreign body removal, esophageal stents, variceal sclerotherapy, laser therapy, control of nonvariceal bleeding, and mucosal resection of superficial tumors.

Magnification endoscopy, chromoendoscopy, narrow-band imaging (NBI), and autofluorescence (AFI) have advanced the diagnostic capabilities of endoscopy in the diagnosis of esophageal disease.

Diagnostic Endoscopy

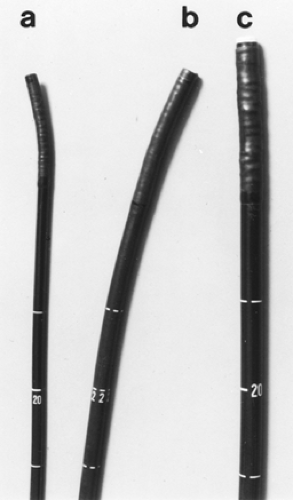

Flexible endoscopes are available in a variety of sizes. Pediatric endoscopes have an external diameter of 7.9 mm and a working channel of 2.0 mm. Routine endoscopes are 9 to 11 mm in external diameter and have working channels of 2.8 mm. Large double-channel endoscopes are 13 mm in external diameter with working channels of 2.8 and 3.4 mm (Fig. 134-1). All flexible endoscopes are long enough to examine the esophagus, stomach, and proximal duodenum. Those with a smaller diameter are used for pediatric patients and adult patients with a narrowed esophageal inlet. Smaller-diameter endoscopes are also helpful in the diagnosis and therapy of strictures. Ultrathin endoscopes with 5.3- to 6-mm insertion-tube diameters and 2-mm biopsy channels have been developed, permitting unsedated transnasal insertion in office settings and eliminating sedation-related complications associated with conventional endoscopy.4 Double-channel endoscopes are useful in the bleeding patient in that one channel can be used for irrigation to visualize the bleeding site better, leaving the other available for applying the appropriate therapy.

The most common indications for esophagoscopy are evaluation of noncardiac chest pain, persistent symptoms of gastro- esophageal reflux, recurrent aspiration pneumonia, dysphagia, odynophagia, and an abnormal esophageal radiograph. Both diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopies are used in the evaluation of patients with foreign bodies, bleeding, achalasia, and strictures. Relative contraindications to endoscopy include medically unstable patients, unstable cervical spine, severe coagulopathy, and known or suspected perforation of the gastrointestinal tract.

Routine elective endoscopy of the esophagus is performed on an outpatient basis. The patient usually fasts 6 to 8 hours before the procedure. Conscious sedation with intravenous midazolam or diazepam and fentanyl is used. Some endoscopists will use propofol for conscious sedation because of its rapid elimination and reduced postprocedure recovery time. Sorbi and colleagues35 have demonstrated the endoscopic accuracy and feasibility of unsedated endoscopy using small-caliber (5.3 to 6 mm) endoscopes.35 Local oropharyngeal anesthesia with lidocaine (Xylocaine) spray is sometimes used.

Direct intubation is achieved by placing the endoscope on the patient’s tongue and guiding it into the posterior pharynx. The epiglottis is located, and once the piriform sinuses are identified posterior to the epiglottis, the endoscope is maneuvered into the esophageal inlet, which is between the piriform sinuses. The posterior pharynx and larynx are examined for abnormalities. The patient is asked to swallow, opening the esophageal inlet and enabling the endoscope to be advanced into the esophagus. The esophageal inlet is usually 20 cm from the incisors. As soon as the endoscope is in the esophageal inlet, the endoscopist begins to visualize the esophagus before pushing the endoscope any farther.

Once intubation is achieved, the endoscope is maneuvered into the stomach and duodenum. Endoscopy is not complete without a careful view of the gastric cardia, achieved by retroflexing the instrument 180 degrees in the antrum and pulling back to paradoxically bring the tip of the endoscope up to the

proximal stomach. Lesions in the cardia—such as tumors, Mallory–Weiss tears, or lesions within a hiatal hernia—are often very difficult to see without this retroflexion maneuver. The lumen should be in view at all times during passage of the endoscope. The lumen is examined while the endoscope is withdrawn.

proximal stomach. Lesions in the cardia—such as tumors, Mallory–Weiss tears, or lesions within a hiatal hernia—are often very difficult to see without this retroflexion maneuver. The lumen should be in view at all times during passage of the endoscope. The lumen is examined while the endoscope is withdrawn.

Figure 134-1. Various endoscopes. A: Pediatric endoscope. B: Routine adult endoscope. C: Double-channel endoscope. |

An old dictum of endoscopy is that one sees only what one is looking for; the patient’s history directs the visualization at endoscopy. Biopsy samples are taken if any abnormalities or possible lesions are seen. Video endoscopes have facilitated efforts to obtain endoscopic pictures and perform video recording of any segment of the procedure.

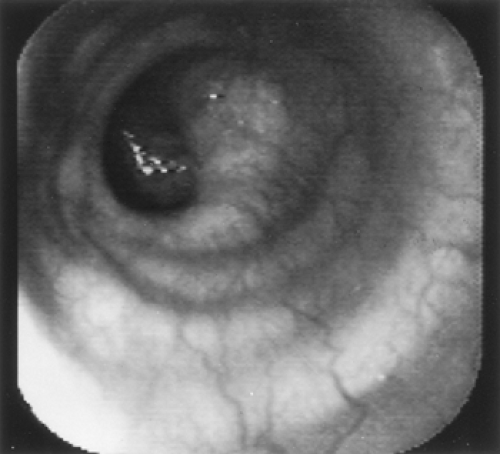

Normal Esophagus

The cricopharyngeus muscle forms the beginning of the normal esophagus, which is a tubular structure until it culminates at the diaphragmatic hiatus. At endoscopy, the esophageal mucosa is smooth and whitish pink (Fig. 134-2). The esophageal lumen is 1.5 to 2.0 cm in diameter. Normally, the aorta gives an extrinsic compression at about 25 cm in the esophagus. Sometimes the left mainstem bronchus can also indent the esophagus below the aorta. The transformation from whitish to reddish mucosa identifies the squamocolumnar junction or Z line. Usually, the Z line is closely related to the diaphragmatic hiatus and is 40 cm from the incisors. The anatomic gastroesophageal junction is clinically defined at the proximal margin of the gastric folds. There is mild angulation of the distal esophagus close to the diaphragmatic hiatus.

The final maneuver to evaluate the esophagus is endoscopic retroflexion in the stomach to identify the presence of a hiatal hernia. A sliding hiatal hernia is identified by a displacement >2 cm between the Z line and the diaphragmatic hiatus, as described by Boyce.8 During the retroflexion in the stomach, if a space between the endoscope and the gastric wall at the cardia is noted, one can also identify a hiatal hernia.

Diseases of the Esophagus

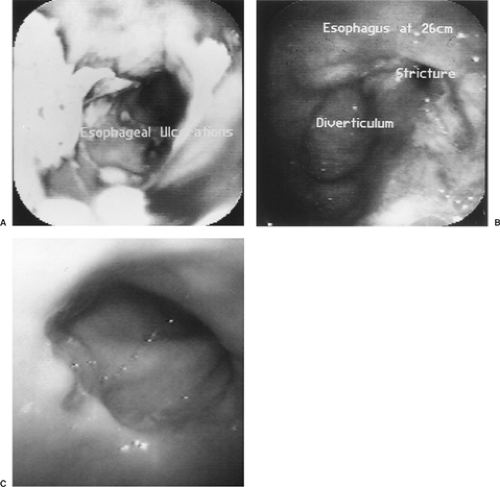

Various disease processes can be identified in patients with dysphagia. Mucosal abnormalities such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), Barrett’s esophagus, Mallory–Weiss tears, infections as noted by Ollyo and associates,28 pill-induced esophagitis, and malignancy can be diagnosed by esophagoscopy. Structural abnormalities such as diverticula, webs, and rings are identified easily by endoscopy and described in detail by Boyce and Boyce.6 Endoscopy is an important step in the evaluation of strictures in that biopsies differentiate benign from malignant strictures.

Endoscopy is very important in detecting and stratifying the extent of suspected GERD. However, the absence of endoscopic features is common and occurs in at least 50% of patients with GERD. Endoscopy therefore should probably be reserved for patients failing to respond to antisecretory therapy, for patients with atypical or alarm symptoms, or for identifying Barrett’s esophagus in those with long-standing symptoms. Endoscopic interobserver variability and the need for consistency in judging treatment response in GERD has led to the development of multiple endoscopic classification schemes. Two of the more popular grading systems (Savary–Miller and Los Angeles) are noted in Tables 134-1 and 134-2. Figure 134-3 demonstrates the appearance of esophagitis and the corresponding classification. Biopsy can be done at the time of endoscopy. Strictures can be dilated, and surveillance for Barrett’s epithelium can be performed.

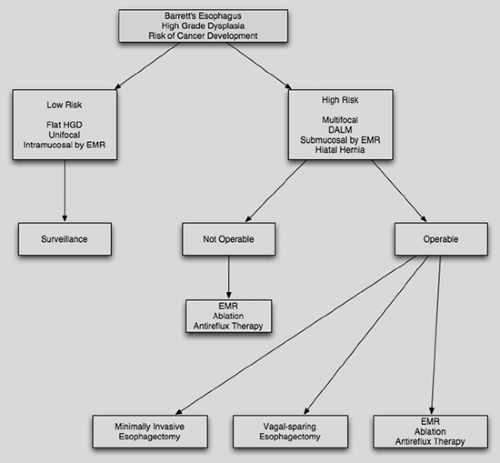

Recognition of Barrett’s esophagus is on the rise in the United States, as is the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Barrett’s esophagus is believed to be the major risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma.41 Dysplasia grade determines

not only the appropriate surveillance interval but also the modalities of therapy. The American College of Gastroenterology in 2008 published their guidelines for surveillance and therapeutic measures (Table 134-3). These guidelines do not go into depth on high-grade dysplasia beyond the use of endoscopic resection. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons is preparing a statement on this subject. In anticipation of publication of these additional guidelines, an algorithm for rational management of the patient with dysplasia is included here (Fig. 134-4).

not only the appropriate surveillance interval but also the modalities of therapy. The American College of Gastroenterology in 2008 published their guidelines for surveillance and therapeutic measures (Table 134-3). These guidelines do not go into depth on high-grade dysplasia beyond the use of endoscopic resection. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons is preparing a statement on this subject. In anticipation of publication of these additional guidelines, an algorithm for rational management of the patient with dysplasia is included here (Fig. 134-4).

Table 134-1 Los Angeles Classification of Peptic Esophagitis | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Table 134-2 Savary—Miller Grading System for Peptic Esophagitis | |

|---|---|

|

Table 134-3 Dysplasia Grade and Surveillance Interval | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

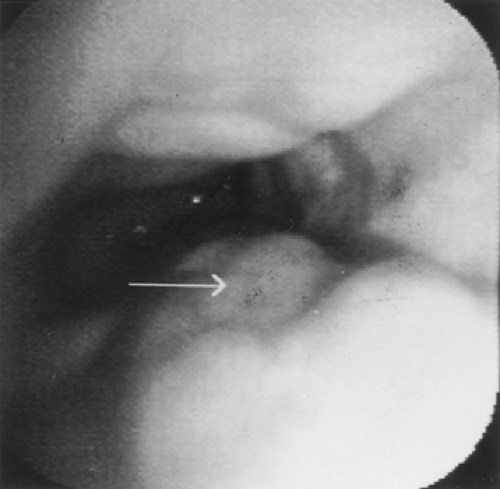

Esophageal varices are best recognized by endoscopy. In patients with portal hypertension and esophageal varices, endoscopy is used for diagnosis and therapy (Fig. 134-5). After initial resuscitation, including the establishment of airway, breathing, and circulation, initial treatment includes early use of vasoactive drug therapy (terlipressin, somatostatin, octreotide).1 When the patient is stabilized, endoscopic band ligation added to somatostatin is associated with improved mortality and less adverse events over sclerotherapy.40

Chromoendoscopy and Narrow-Band Imaging

Absorptive or vital stains can be sprayed on the esophageal mucosa to increase detection of Barrett’s esophagus or tumor. Lugol’s 1% or 2% solution binds to glycogen in nonkeratinized squamous epithelium. Glycogen-depleted areas—including ectopic mucosa, ulcers, cancers, and severe dysplasia—will not take up the stain.42 Canto10 demonstrated that methylene blue spraying at the time of endoscopy will reliably stain Barrett’s mucosa and improve the yield of diagnosing high-grade dysplasia. Since classification of mucosal staining is not standardized as well as being subject to observer variability, chromoendoscopy is not sufficiently validated for routine endoscopic practice.42

Figure 134-4. Decision tree for the management of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. HGD, high-grade dysplasia; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; DALM, dysplasia-associated lesion or mass. |

Narrow-band imaging exploits the phenomenon that the depth of light penetration into tissues depends on wavelength. The combination of blue light absorption by hemoglobin and the utilization of optical filters yields enhanced mucosal architecture while revealing mucosal vascular patterns.20 However, an additive benefit to chromoendoscopy or NBI over high-resolution magnification endoscopy in the detection of early Barrett’s neoplasia could not be demonstrated.11 In 2008, an international multicenter feasibility study of endoscopic trimodal imaging (high-resolution endoscopy, NBI, autofluorescence) revealed an increase in the number of patients and lesions detected when autofluorescence was combined with high-resolution endoscopy. AFI, however, was associated with an 81% false-positive rate, which “was reduced after detailed inspection with NBI.”12 Further investigation is necessary to elucidate the impact of chromoendoscopy, NBI, as well as AFI on the detection of early Barrett’s neoplasia. Advanced imaging systems including NBI, AFI, as well as confocal microscopy remain promising modalities to evaluate Barrett’s esophagus, but at present there are insufficient data to recommend their routine utilization.41

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree